She had spoken of a ‘sacrifice.’ That was the naked truth of it; any moment tragedy might be done, some hideous rite consummated, and youth and gallantry laid on a dark altar.

(The central threat in The Dancing Floor, page 150)

There was business afoot, it appeared, ugly business.

(Reaction of plucky young Vernon Milburne when he hears of a damsel in distress, page 198)

Frame story

As with The Power-House and John McNab, this is another frame story, although the frame is brief and cursory, less than half a page. It says that the unnamed narrator heard this tale from Leithen himself, ‘as we were returning rather late in the season from a shooting holiday in North Ontario’.

I think this single paragraph does at least four things. First and foremost it announces that we are going to hear a long yarn, of a certain comfortable, clubbable, fireside type. Two, it establishes that we are, as usual with Leithen, moving in posh English circles, among hunting, shooting and fishing types. And three, the unexpected setting, North Ontario, announces that we are among the British ruling class which is used to taking the world as its oyster, which thinks nothing of travelling to Canada, Australia, India or South Africa, for recreation and amusement. In this respect it 4) prepares us for the way this spooky horror story is going to be set in Greece, in that era still a faraway destination, full of uncanny pagan beliefs, as the story will amply demonstrate.

A Leithen story

The first-person narrator claims to have been told this story told by the Buchan character, Sir Edward ‘Ned’ Leithen, barrister and Conservative MP, making this the third of the five Leithen novels.

Part One

Chapter 1

So the story gets going in January 1913, with Leithen describing meeting a friend of his nephew, Charles, at a posh ball. The friend is a tall, slender, aloof young man named Vernon Milburne. Brief party conversation.

Three months later, at Easter, Leithen takes a break from his busy work schedule for a brief walking holiday in the Westmoreland hills, what we call the Lake District. On the last day he twists his ankle, the weather turns bad, he gets lost and is lucky to end up walking up the drive and knocking on the front door of a big old mansion belonging to…guess who! The very same Vernon Milburne, living all alone in the Gothic monstrosity built by his grandfather, attended on by an ancient butler.

This so-far pretty prosaic account takes a turn for the supernatural. For after they’ve taken his boots off and treated his ankle and given Leithen a nice hot bath and clean clothes, after the staff have served up a lovely hot dinner, then young Vernon hesitantly tells Leithen that he has been haunted by dreams since boyhood. To be precise, every spring he is revisited by the same dream in which he is in a strange house with the terrible knowledge that something momentous is moving through the rooms towards him. With each spring that passes, the dream recurs and The Thing is one room closer.

Chapter 2

Over the next few years Leithen stays in touch with young Vernon and they regularly meet up for lunch or dinner. He tries to help the boy by doing in-depth research into his family tree in the vague hope of discovering either a strain of psychic weirdness or maybe some traumatic event which Vernon is channeling.

In spring 1914 Leithen is invited by a friend (the Earl of Lamancha who is one of the three protagonists of the previous book in the series, John McNab) to join him on his yacht for a cruise around the Greek islands, and he invites Vernon along. He discovers Vernon has a very strong feel for the primal Mother Goddess who he considers the centre of Greek religion and forerunner of the Virgin Mary. On a walk round a remote island they’ve anchored at, they come across a large mansion and are startled when local fishermen give cries of terror and cross themselves on seeing Vernon. Why?

On the cruise he has the same dream again. By his reckoning there are six more rooms for The Thing he so strongly feels looming in his dream to traverse – six more years before the secret of his dreams is revealed.

Unfortunately, the First World War intervenes. From various sources Leithen (who volunteers and fights for the duration) discovers that Vernon is a very dutiful and logical soldier but lacks the real urge to hatred and violence. He is strangely detached from the whole thing.

Towards the end of the war, Leithen is gassed and spends weeks in a hospital bed recovering. In the way of outrageous coincidences which characterise popular yarns, Vernon happens to be in the bed next to him. He has had a good war and risen to the rank of colonel (p.205).

Chapter 3

The lad recovers and goes off but Leithen’s health is permanently undermined. He does lots of things to try and recapture the good health of his youth, looking out his old university books, even moving into the rooms he and friends shared at Oxford.

He gets a letter that Vernon has been sailing in the south of France and that reminds him of the eerie morning on the Greek island before the war. Leithen happens to have an old relic of the 1890s staying with him, old Folliot, a memoirist who’d made a career writing about 50 years of dining at other men’s tables. When Leithen asks him about the Greek island he and Vernon spent that weird morning on, Plakos, it triggers a long stream of information from Folliot.

Turns out the island was bought by a renegade Englishman named Tom Arabin, a wastrel and bounder from way back, ‘a shabby old bandit,’ who built himself a mansion on the house and had all sorts of rascal friends to stay. He had actually known Byron and Shelley. So much so that he named the son he had and raised on the island Shelley, Shelley Arabin. Good-looking young chap, expert writer, took the decadent style of Baudelaire and Swinburne a step further.

Good-looking but cold and cruel, and rumours spread about his wicked behaviour as he turned the mansion into a refuge for:

soldiers of fortune, and bad poets, and the gentry who have made their native countries too hot for them. Plakos was the refuge of every brand of outlaw, social and political.’

Folliot heard gossip about scandalous behaviour from our man in Athens, a certain Fanshawe, who marvelled that the islanders didn’t burn down the den of iniquity the villa had become.

Well, this explains to Leithen the very powerful vibe of evil and discomfort he’d felt when he and Vernon stumbled over the place on their innocent stroll. To the reader the way the Greek fishermen they happened across leapt aside and made the sign of protection against the evil eye…well, that immediately made me think that young Vernon is, in the way familiar from a thousand horror stories, a reincarnation of wicked Shelley Arabin!

Chapter 4

The plot thickens then thickens some more. Leithen is at a country house party, at a place called Wirlesdon whose owners, Tom and Molly, are old friends, for the shooting (the book contains numerous references to not only shooting game but fox hunting, with knowing references to various well-known ‘hunts’ across England). Here he sees a young woman behaving with astonishing rudeness, domineering and masterful, who demands a cigarette, a light and then conversation with young Vernon who is, understandably, put off by her rudeness. Leithen learns she is named Corrie and assumes she is some jumped-up chorus girl.

The hostess, Mollie Nantley, then informs him that this woman is none other than the daughter of Shelley Arabin, brought up in a house of sin and decadence.

Chapter 5

Then, as so often with the Leithen stories (The Power-House depends on it) he finds out more via his work as a barrister, this being a way of shoehorning outrageous coincidences into the plot. A brief comes his way which he is surprised to see concerns the island of Plakos and the former owner Shelley Arabin.

From this Leithen learns that Corrie’s real name is Koré, the classical Greek term for young woman. And it takes a while to disentangle the fact that the case has been cooked up by the old solicitor for the family, a Mr Derwent, in a bid to rescue Koré. The idea is that the Arabin family were already very unpopular but that the privations of the war, coming close at times to starvation, have inflamed the sense of grievance among the ‘primitive’ islanders. There have been threats against her and Derwent is worried for her safety. And so he was involved in the law case Leithen has come across, in which an anonymous buyer was proposed to buy the mansion and all the property off Koré and so free her from threat.

Derwent is discreet about who this mysterious benefactor is but Leithen takes a guess that it is the wealthy Jewish banker Theodore Ertzberger, who Koré stayed with as a girl during her education in England. So he goes to visit Mr Ertzberger, who confirms the story and adds a lot more detail about the danger Miss Arabin is in back on Plakos. He also adds depth to the black character of Shelley Arabin.

‘The man was rotten to the very core. His father – I remember him too – was unscrupulous and violent, but he had a heart. And he had a kind of burning courage. Shelley was as hard and cold as a stone, and he was also a coward. But he had genius – a genius for wickedness. He was beyond all comparison the worst man I have ever known.’

And the danger Koré is in among islanders who some of whom consider her a witch. So Ertzberger begs Leithen to take her case and help her.

Chapter 6

Over the next couple of weeks Leithen has random sightings of Koré, in a train carriage then, again, on a train platform with a group of other young people waiting for a train. These sightings are designed to build up the sense of Koré as aloof and distant and lonely and separated from her peers by a terrible upbringing and present danger. It is around Christmas time.

One night he returns from work at his chambers in the Temple (the Temple is a set of buildings in east central London entirely devoted to the chambers of barristers and lawyers) to discover a great pile of family records and documents has been delivered to his house, a ramshackle assortment of all sorts of documents including diaries and letters of wicked old Shelley. In among them was an old envelope containing what looks like a very old manuscript written in Greek. He sends this onto a fellow lawyer who as a hobby is interested in the Classics. He transcribes it a pronounces it fascinating but can’t actually translate it. So Leithen sends it on to Vernon who, conveniently enough, studied Classics at Oxford.

(Worth pointing out that Leithen has been saddened at their recent meetings to realise that Vernon is drifting away from him; they no longer share the friendship and regular meetings they had before the war.)

The manuscript turns out to describe the Spring festival of welcoming the Queen or ‘Fairborn’ at a place named Kynaetho. It quotes old paeans, Greek poetry and rituals, to describe the Koré or the Maiden. But it goes on to mention that in times of great distress a different ceremony is held, and the document seems to describe is the human sacrifice of a young man and woman in order to bring Spring and fertility to the land.

A few days later Koré phones him, asks if he has read the papers, then domineeringly invites him for luncheon. Here Leithen summarises the situation:

‘Your family was unpopular – I understand, justly unpopular. All sorts of wild beliefs grew up about them among the peasants, and they have been transferred to you. The people are half savages, and half starved, and their mood is dangerous. They are coming to see in you the cause of their misfortunes. You go there alone and unprotected, and you have no friends in the island. The danger is that, after a winter of brooding, they may try in some horrible way to wreak their vengeance on you.’

Koré accepts all this but obstinately refuses to do the sensible thing, namely sell up and move back to England. She goes on to deepen the sense of voodoo threat, explaining that some of the islanders accuse her of being a diabolissa (a she-devil), a trigla (a harpy) or vrykolakas (a vampire), they wear blue beads round their necks and always have garlic on them to protect themselves and their children from her, whisk children out of the street when she passes, and so on. Ertzberger, in their earlier interview, had given one reason for her obstinate insistence on staying.

‘I think she feels that she has a duty—that she cannot run away from the consequences of her father’s devilry. Her presence there at the mercy of the people is a kind of atonement.’

We are on page 100 of this 250-page book and it is plain that we have been very slowly, very painstakingly sucked into the intense, Hammer Horror plight of this young lady. And Leithen is hooked:

The fact was that I was acquiring an obsession of my own – a tragic defiant girl moving between mirthless gaiety and menaced solitude. She might be innocent of the witchcraft in which Plakos believed, but she had cast some outlandish spell over me.

As they talk, Leithen suddenly has what you might call the Quintessential Buchan Epiphany, which is the sudden sense of the thin line separating barbarism and civilisation; more precisely that you can be in busy old London, in a London street or a London flat and everything looks and feels normal but somehow, some secret knowledge, knowledge of a secret plot or conspiracy or hideous plight, transforms everything.

This is the feeling of terror and vertigo which Leithen experiences in the latter stages of The Power-House when he has to trek across a London packed with the spies of the secret organisation which is out to murder him, and this is the feeling he suddenly has, sitting listening to Miss Arabin tell her spine-chilling stories of ancient rituals, blood letting and human sacrifice on a remote island.

Anyway, the key fact which emerges is that all these revelations are happening just after Christmas and the New Year and Koré is not planning to return to the island until March – which is, of course, as the build-up to the spring festivals begins and also, when Vernon’s recurrent nightmare afflicts him (start of April). This chapter (6) ends on a deliberate cliff-hanger when Leithen asks Kore if she’s ever heard of a place called Kynaetho, and she tells him it’s the name of the biggest village near to her house! My God, all those bloodthirsty ancient rituals stem from right next door to where she lives!

Chapter 7

Leithen is now obsessed with the figure of this slender Englishwoman, hard as nails on the outside, sensitive and terrified inside, and the weird and horrific and primal pagan danger she finds herself in.

a solitary little figure set in a patch of light on a great stage among shadows, defying of her own choice the terrors of the unknown.

Madly, he sometimes thinks he’s falling in love with her, toys with proposing to her, that a wealthy older man could protect her. Then Koré leaves. She’s due at a dinner party but never shows up. Leithen enquires at her solicitors and discovers she’s packed and left for Greece. He confers with Ertzberger who tells him Koré has sold off all her investments for cash, which suggests she’s going to do something reckless or dangerous. So Leithen winds up his affairs and leaves London that weekend.

Part two

Chapter 8

Leithen arrives in Athens. Ertzberger had given him the name of a contact, Captain Constantine Maris. This man has gathered a ragtag squad of recruits in case things get rough. They’re a rough-looking bunch. They have a stormy voyage from Athens to Plakos (aboard ‘a dissolute-looking little Leghorn freighter, named the Santa Lucia’) and are put ashore in a deep fog.

Turns out they’ve landed on the wrong jetty, the one below the village, not the house. They soon trigger a wary terrified crowd of villagers who lead them to the village priest. An old bent man he repeats the villagers’ beliefs that Koré is a witch and should be driven from the village and her house burned down, but doesn’t want her harmed because he doesn’t want his villagers to have a mortal sin (murder) on their consciences. So he is prepared to help Leithen get into the big old house, despite every approach being guarded by villagers.

Meanwhile, Maris will walk south along the coast to the next village of Vano where, for obscure reasons, they decided to land a second force (of five) under the second-in-command, one-armed Janni (wounded in the war). How this all turned into a military assault is an authorial sleight of hand and why, a bit of a mystery.

Chapter 9

Leithen spends the long hot day in the care of the local priest waiting for nightfall. They fall upon the expedient of writing messages to each other in rough Latin and the priest emphases the peril, the danger etc, chiefly to stoke up a sense of genuine panic in the reader. Eventually night falls and Leithen slips out the back of the priest’s house and heads towards Kore’s mansion along the raised shoulder of flat land the locals call the Dancing Floor (where ancient ceremonies used to be held). It’s amusing the way Leithen the narrator keeps telling us how dull and prosey he is before going into a great dithyramb (‘A dithyramb is a speech or piece of writing that bursts with enthusiasm. ‘):

You will call me fantastic, but, dull dog as I am, I felt a sort of poet’s rapture as I looked at those shining spaces, and at the sky above, flooded with the amber moon except on the horizon’s edge, where a pale blue took the place of gold, and faint stars were pricking. The place was quivering with magic drawn out of all the ages since the world was made, but it was good magic. I had felt the oppression of Kynaetho, the furtive, frightened people, the fiasco of Eastertide, the necromantic lamps beside the graves. These all smacked evilly of panic and death. But now I was looking on the Valley of the Shadow of Life. It was the shadow only, for it was mute and still and elusive. But the presage of life was in it, the clean life of fruits and flocks, and children, and happy winged things, and that spring purity of the earth which is the purity of God.

Leithen makes an attempt to break into the demesne or land of the house by getting through what looks, at a distance, like a breach in the wall. But a) it is guarded and b) when he makes a bolt for it he finds out the hard way that it is completely blocked by a stout wooden gate, so he turns tail, howling and waving his arms in the manner of a banshee to freak out the peasant Greek guards and makes it all the way back across the meadow of the Dancing Floor without anyone firing on him. And then through bushes, along the path above the village cemetery and so back to the priest’s house, having completely failed in his mission.

He goes to the inn to discover the men he left there have gone, then out into the village street, at dawn, where a menacing crowd is gathering so he breaks into a run and sprints to the church, bursting through the doors and none of the villagers follow him.

Chapter 10

Leithen spends the day with the priest with whom he forms a bond, after praying by the side of the bier containing an effigy of Christ ready for the Easter festival and then Leithen helps wash and scrub the floor of the little old church. As night falls Maris appears at the window and reveals that all the other men have deserted. He headed south and rendezvoused with Janni only to discover that Janni’s five men had been so demoralised by chatting to the local peasants, who told them about the witch who poisoned the land, that they had asked permission to go home. And when he got back, Maris found his five had also deserted.

At night Leithen heads across country to meet up with Janni. This is beginning to feel needlessly drawn out and complicated. They go round the coast trying to find a way to climb the cliffs into the land of the big house but instead discover a yacht anchored out in the bay. Leithen strips and swims out to it and discovers it is crewed by a Greek who speaks no English and has been told to remain there until the return of his master, who has gone ashore.

Leithen persuades the man to row the yacht’s dinghy to shore where Janni, of course, can communicate with him. They tell him about the English girl who is in distress and get him grudgingly to promise to come and rescue them if they can get the girl down to this bay.

Chapter 11

God, this is getting complicated. Then Janni and Leithen head back to the ‘base’ and crash out, exhausted (the place on the bare downs where Leithen had encountered Janni at the start of chapter 10). The Penguin edition has a map of the island but I’m not sure it helps that much.

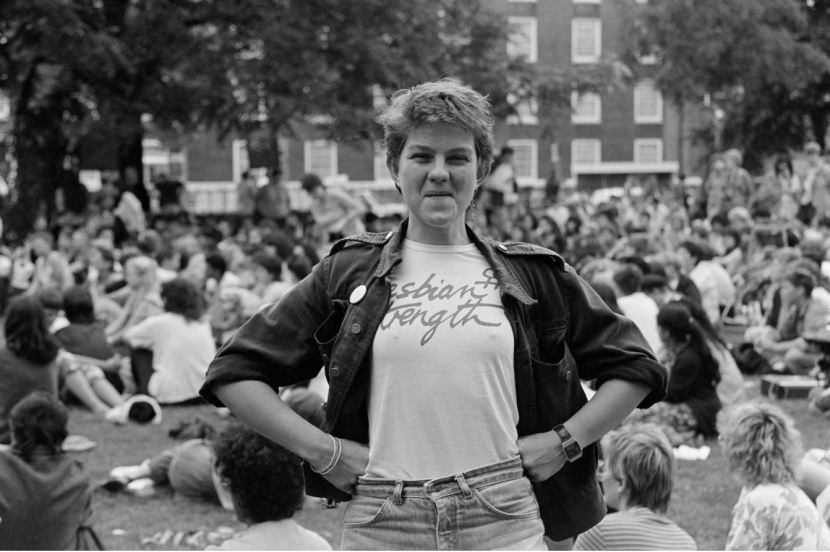

Map of (the southern part of) the fictional Greek island of Plakos showing The House where Kore is holed up, the village of Kynaetho to its north and the great extent of meadow called the Dancing Floor to the East, with Janni’s encampment on the eastern shore

Leithen wakens the next morning as Janni is cooking breakfast. At 1pm he approaches the mansion from the sea side but is dismayed to find it is completely surrounded by guards and that the villagers have made piles of firewood against all of the doors. They really do plan to burn the place down!

That night he returns with Janni, edging their way round the walls or cliffs or something to try and find a way to the house, when they come across an extraordinary sight: the Dancing Floor has been adorned as for a ritual. Flaming torches stand at intervals and the entire village has turned out to watch.

What the watch is a bunch of youths running round the perimeter of the floor several times, before the winner grabs the last torch as he runs past it, and runs into the centre of the meadow and douses the torch in a spring. Then another man, obviously a prisoner, is brought forward, has his shirt torn from him and is doused with water from the spring. Leithen realises two things: this is exactly the ritual described in the manuscript he found among the papers which Koré gave him. And the man is Maris, his erstwhile helper. Leithen realises he has been chosen as the sacrificial man who will join the sacrificial woman, Koré, when the house is burned down, a ritual sacrifice to revitalise the sterile land.

He feels himself overwhelmed by pagan feelings, an overwhelming need to worship, feels the caveman rising in him. It is only by fixing his thoughts on the wooden figure of the crucified Christ that he hangs onto his sense of civilisation and values.

I am not a religious man in the ordinary sense—only a half-believer in the creed in which I was born. But in that moment I realized that there was that in me which was stronger than the pagan, an instinct which had come down to me from believing generations. I understood then what were my gods. I think I prayed, I know that I clung to the memory of that rude image as a Christian martyr may have clung to his crucifix. It stood for all the broken lights which were in me as against this ancient charméd darkness. (p.171)

In that hour the one thing that kept me sane was the image of the dead Christ below the chancel step. It was my only link with the reasonable and kindly world I had lost. (p.175)

Chapter 12

The entire village is camping out on the Dancing Floor, so when Janni and Leithen sneak back into the village they discover it is empty. They return to the church where, bizarrely and surreally, since they are the only people around, the priest dragoons them into carrying the bier containing the wooden effigy of Christ around the bounds of the village. What emerges clearly is that, although Leithen considers himself only a half believer, still, the Christianity he learned as a boy

I am not a religious man in the ordinary sense—only a half-believer in the creed in which I was born. But in that moment I realized that there was that in me which was stronger than the pagan, an instinct which had come down to me from believing generations. I understood then what were my gods.

And so carrying the bier is an act of defiance against pagan barbarism.

We were celebrating, but there were no votaries. The torches had gone to redden the Dancing Floor, sorrow had been exchanged for a guilty ecstasy, the worshippers were seeking another Saviour. Our rite was more than a commemoration, it was a defiance, and I felt like a man who carries a challenge to the enemy.

Then there is an incredibly long, drawn-out description of him and Janni approaching the causeway and jetty to the house, Janni going off in one direction to act as a distraction, while Leithen crawls the other way, under the wall of the causeway, it’s the middle of the day and blistering hot, till he comes to wall which he follows for a while and finally, finally, scrambles over it and into the demesne of the bloody house.

He is running through the large garden towards the house when he sees a tremendous whoosh of flame go up into the night sky. The villagers have started the fire! For some reasons numbers of the hillmen who had been guarding the house comes stumbling past him with terror in their yes. Why? Then he stumbles into Maris, who also is wild-eyed but recognises him, is free, and has his pistol. Will they need it?

Part 3

Chapter 13

Part 3 cuts away from the present action to jump back to Vernon. You might well have forgotten but this is the spring when the sequence of his dreams is finally meant to result in the Big Thing arriving, the thing which has been moving one room, one year at a time, towards him, the great revelation.

So that spring Vernon left London to travel to Greece, as he had many times before. He travelled by train to Venice where he joined his yacht which had been shipped there. Then we get a long, over-detailed description of his journey by sea, sailing a yacht from Italy, through the Corinth canal, up the east coast of the mainland etc etc.

He had no plans. It was a joy to him to be alone with the racing seas and the dancing winds, to scud past the little headlands, pink and white with blossom, or to lie of a night in some hidden bay beneath the thymy crags. He had discarded the clothes of civilization. In a blue jersey and old corduroy trousers, bareheaded and barefooted, he steered his craft and waited on the passing of the hours. His mood, he has told me, was one of complete happiness, unshadowed by nervousness or doubt. The long preparation was almost at an end. Like an acolyte before a temple gate, he believed himself to be on the threshold of a new life. He had that sense of unseen hands which comes to all men once or twice in their lives, and both hope and fear were swallowed up in a calm expectancy.

So 1) the notion of leaving ‘civilisation’ behind is again invoked, along with 2) images of pagan religion, the ‘acolyte’ at the ‘temple gate’ and 3) the sense, in the final sentence, of a controlling destiny.

The stormy seas he and his shipmate (an unnamed Greek sailor he picked up in Epirus) last for days of perilous sailing in high seas and adverse winds and, at the end of it, he realises the Great night has passed and he did not have the dream. The great climax, the revelation of the meaning of the recurring dream he had been having for at least ten years and which he had so nervously revealed to Leithen that evening before the war, had simply not arrived (p.193). He feels like a fool for wasting the best years of his life keyed up for a fantasy.

The thing is, after all their wild sailing across the Aegean, they have at last stumbled across an unnamed island and, as a thick fog swirled up, have anchored in a small bay. The make food and coffee and Vernon is sitting on deck mulling over his folly in wasting his life on a phantom when…a face appears at the gunwales! An old Greek has spotted their yacht and rowed out to greet it. When he sees that the master of it is a young Englishman, he begs for his help.

Because guess what island Vernon has come to out of the huge number of little Greek islands available, guess which one he just happens by complete accident to have come across, and guess just which bay he has, completely at random, anchored in?

Yes. Plakos! And he has cast anchor in the little harbour below THE HOUSE which is at the centre of the whole melodrama! The coincidence is so forced and preposterous that the reader can only marvel at what Buchan himself would probably call its ‘bare-faced cheek’.

Anyway, this old Greek servant in a dinghy persuades Vernon that his mistress is in great danger and wants him to come and talk to ‘Mademoiselle Élise’ waiting ashore. So Vernon grabs a cap and a revolver and is slowly rowed by the whiskery old boy through the fog the short distance to the jetty below The House.

Here Mademoiselle Élise (‘a middle-aged woman with the air and dress of a lady’s maid’) hurriedly recaps the story which we, the readers, already know inside out, about the obstinate Englishwoman, scion of a wicked family, barricaded into her own mansion by enraged villagers etc. Vernon, being a stout chap, accepts the preposterous story and promises to help a damsel in distress. So the servants guide Vernon, tiptoeing through the fog (to avoid alerting the guards Leithen has spent four days trying to dodge) and achieve at a stroke what Leithen had completely failed to do, namely find the one door into the building which isn’t blocked up with piles of firewood, unlock it and, hey presto! Vernon is inside the dank, mouldering old building.

Chapter 14

He finds himself in a massive room painted with a mural.

It was the walls, which had been painted and frescoed in one continuous picture. At first he thought it was a Procession of the Hours or the Seasons, but when he brought his torch to bear on it he saw that it was something very different. The background was a mountain glade, and on the lawns and beside the pools of a stream figures were engaged in wild dances. Pan and his satyrs were there, and a bevy of nymphs, and strange figures half animal, half human. The thing was done with immense skill— the slanted eyes of the fauns, the leer in a contorted satyr face, the mingled lust and terror of the nymphs, the horrid obscenity of the movements. It was a carnival of bestiality that stared from the four walls. The man who conceived it had worshipped darker gods even than Priapus. There were other things which Vernon noted in the jumble of the room. A head of Aphrodite, for instance – Pandemos, not Urania. A broken statuette of a boy which made him sick. A group of little figures which were a miracle in the imaginative degradation of the human form. Not the worst relics from the lupanars of Pompeii compared with these in sheer subtlety of filth. (p.201)

And the sickeningly realistic painting of Salome with the head of John the Baptist. And the exquisitely bound collection of pornography through the ages. The servants show him to a poky attic room where he lies down and sleeps for 10 hours (exhausted by the ordeal of the stormy sailing).

Next morning he’s given hot water for a wash and shave but still looks sunburned and rough, in his corduroy trousers and no shoes when he is introduced by the servants, to his amazement, to none other than Koré Arabin, the pesky young woman who he met half a dozen times at country house weekends back in England… What the devil?!

It’s a shock for both of them to recognise each other and even Buchan realises this is now a series of preposterous coincidences:

‘You have forgotten,’ she said. ‘But I have seen you out with the Mivern, and we met at luncheon at Wirlesdon in the winter.’ He remembered now, and what he remembered chiefly were the last words he had spoken to me on the subject of this girl. The adventure was becoming farcical.

What’s striking or funny or characteristic or a lot like a movie, is that the young woman at the centre of this overripe farrago turns out to be every bit as sarcastic, superior and obstinate as she was when Vernon and Leithen first met her in the drawing rooms of English country houses.

They quickly catch up with the situation – villagers think she’s a witch, they’re going to carry out the ancient ceremony to burn the house down and cleanse the evil etc etc – and Vernon insists she must come with her now. She refuses. He says he’ll carry her by force, if necessary. Suddenly, in my mind’s eye, I saw the dashing heroes of silent cinema, Douglas Fairbanks, Rudolf Valentino, rescuing a fair maiden in distress! To show her pluck, Koré pulls a small hand pistol on him. To show his, he snatches it out of her hand (discovering it was unloaded, anyway)!

Anyway, she now walks him to the window, shows him the bay and the fact that the fog has completely disappeared and so has the yacht which brought him. It has sailed away, probably alarmed by her village guardians some of whom are setting out on their own fishing boats. Vernon is a prisoner like herself!

Chapter 15

At this moment of peril, Vernon feels new purpose and energy. Accompanied by the stirrings of feelings for this plucky gal.

He understood the quality of one whom aforetimes he had disliked both as individual and type. This pale girl, dressed like a young woman in a Scotch shooting lodge, was facing terror with a stiff lip. There was nothing raffish or second-rate about her now.

Now they’re stuck together, she tells him more. The most important detail is the food. Although they are blockading the house, the villagers are bringing good food – barley cakes, honey and cheese, eggs and dried figs, along with plenty of milk, and fresh water. Odd, given that the villagers themselves have endured a semi-famine.

But Vernon realises its significance. This is the food you give to sacrificial victims. It is recorded in that ancient manuscript Leithen had passed on to him. And thus they draw closer and closer together, Vernon realising she is not at all the spoiled brat she came over as in their previous encounters but a woman with a core of steel, determined to pay back the debt incurred by her decadent forebears, determined to see it out to the last.

Talking to the ancient servant Mistri Vernon learns that the day appointed for the ceremonial burning of the house is three days hence on Good Friday. He also learns about the ceremony which is held a day or two prior to this, the race among the young men of the village on the Dancing Floor as soon as the moon rises, and the victor being crowned King and choosing the male sacrifice – the event Leithen observed in Part 2.

Aha! Vernon conceives a plan. He will get Mitri to smuggle him out of the house, he will get Mitri to put it about that he (Vernon) is a native of a remote mountain village. He speaks Greek. His face is brown from sailing. He will pass as a local, take part in the race and win. Koré is puzzled when he tries to explain, so he puts it in pukka English tally-ho style:

Since Koré still looked puzzled, he added: ‘We’re cast for parts in a rather sensational drama. I’m beginning to think that the only way to prevent it being a tragedy is to turn it into a costume-play.’ (p.221)

Chapter 16

Vernon climbs down a drainpipe, makes his way to the causeway, and bluffs his way past the guards, using his passable Greek (wildly improbable). Walks east round the coast till he sees his yacht anchored in the other bay, the one where Leithen and Janni had seen it. He swims out to it and is reunited with his loyal Epirote who has some choice insults to hurl at the people of Plakos who chased him away from the main harbour more or less at gunpoint.

It’s at this point that this Epirote (who we learned in the Leithen chapters is called Black George) tells Vernon that the day before an Englishman had swim out to the boat, made him row the dinghy to the shore where he’d met the man’s Greek assistant, and they’d told a wild tale about a woman in danger.

This is, of course, Leithen and Janni whose version of this event is given in Part 2. The two strands of narrative are converging.

To cut a long story short, Vernon mixes in with the village crowd heading towards the Dancing Floor for the evening of the race and manages to become one of the young men jostling around the start of the race. As we know, after a slow start, Vernon goes on to win, grab a torch, run to the sacred well in the centre of the meadow and dowse the torch, then listen to the instructions of the priest and master of ceremonies. This man makes it clear that Vernon’s role is to be placed inside the house and wait till the first fires are lit before murdering its inhabitants, then being let out by whichever door he exits to watch the climax of the ceremony.

Then the priest asks him to choose the male sacrifice and armed men bring forward Maris, Leithen’s assistant who had been captured. Vernon spots that he is unwilling and has the manner of a soldier so on the spot chooses him, he has a vase of holy water poured over him, then is manhandled alongside Vernon up to the house, to be sent inside.

Chapter 17

Once they’re inside the house Vernon reveals to Mitri who he is and the latter astonishes him by saying he has come to the island with an English colonel and Milord. Good grief! Leithen!! Vernon realises Leithen is in on the game.

Back to the present they have 24 hours to prepare (until Good Friday night) but are at a loss how to escape once the fire is lit because all exits will be thronged with fanatical villagers, who’ve been led to believe (it’s now made clear) that the whole ritual will lead to the advent of THE OLD GODS, a god and goddess risen from the ashes.

‘We are dealing with stark madness. These peasants are keyed up to a tremendous expectation. A belief has come to life, a belief far older than Christianity. They expect salvation from the coming of two Gods, a youth and a maiden. If their hope is disappointed, they will be worse madmen than before.’

Over the course of many fretful hours and intense conversations, they try to come up with an escape plan. The two servants will be allowed to leave by the mob outside, but as to Koré, how can Vernon get her out of the house and down to his yacht, how can he get his man to bring it round to the bay of the mansion etc?

Suddenly they jointly reach a realisation: they will give the villagers their gods. They enter a kind of visionary state whereby they both realise this is their destiny. Certainly this is the strange destiny the long story about Vernon’s nightmares from the start of the book, now seems to have been heading towards.

By very different roads both had reached a complete assurance, and with it came exhilaration and ease of mind…The only problem was for their own hearts; for Koré to shake off for good the burden of her past and vindicate her fiery purity, that virginity of the spirit which could not be smirched by man or matter; for Vernon to open the door at which he had waited all his life and redeem the long preparation of his youth. They had followed each their own paths of destiny, and now these paths had met and must run together.

So the text now partakes of the same visionary intensity as the villagers. Everyone has entered this state of religious exaltation.

Chapter 18

Chapter 18 cuts back to Leithen’s point of view. You may remember we left him charging through the gap in the wall and into the garden or olive grove just as the guardians of the house set it alight. He sees flames licking at the building and climbing into the sky but more immediate is that he keeps bumping into armed guardians of the house who are fleeing in terror.

Long story short, Koré and Vernon have exited the house dressed in immortal white and are processing, slowly and stately, as if they are the old pagan gods born again and Leithen himself is caught up in the panic hysteria.

What I saw seemed not of the earth – immortals, whether from Heaven or Hell, coming out of the shadows and the fire in white garments, beings that no elements could destroy. In that moment the most panicky of the guards now fleeing from the demesne was no more abject believer than I… For a second I was as exalted as the craziest of them. (p.246)

Even when he realises that it is Koré and Vernon, they are transformed:

It was not Koré I was looking at, but the Koré, the immortal maiden, who brings to the earth its annual redemption…What I was looking at was an incarnation of something that mankind has always worshipped – youth rejoicing to run its race, that youth which is the security of this world’s continuance and the earnest of Paradise…I recognized my friends, and yet I did not recognize them, for they were transfigured. In a flash of insight I understood that it was not the Koré and the Vernon that I had known, but new creations. They were not acting a part, but living it. They, too, were believers; they had found their own epiphany, for they had found themselves and each other. (p.247)

The impact on the assembled crowd is dramatic. At first the Dancing Floor is packed with villagers and people from the mountains gathered to witness this mystery and they watch in holy awe. Then a great ripple goes through the crowd and it breaks and panics. Everyone turns and runs. Soon the Dancing Floor is empty.

Leithen turns to Maris and orders him to go alert the yacht to move in closer (he still doesn’t realise it’s Vernon’s yacht, thinks they’re just dealing with Black George). Leithen runs forward and embraces Vernon and Koré who are both now coming down off their high of exaltation, and starting to show the effects of nervous exhaustion. He helps them along the street to the main harbour, and they all – Koré and Vernon, Élise and old Mitri, Maris and Janni, and Leithen – go aboard the yacht and cast off.

That’s it. They are saved with not a shot fired and no-one harmed. The wicked old house of sin has gone up in flames. And the terrified locals have fled to the church which they are packing out and pleading for mercy from the Christian God they had shunned. Everything sorted. Happy ending.

And Leithen has the last word, lighting a pipe as the dawn wind freshens and looking at the young lovers who have fallen into a dead sleep. He concludes the story with a sentiment which would have warmed most reader’s hearts until the last few generations, a vision of heteronormativity, for he wonders how these two strange, obstinate young people will actually fare together.

How would these two, who had come together out of the night, shake down on the conventional roads of marriage? To the end of time the desire of a woman should be to her husband. Would Koré’s eyes, accustomed to look so masterfully at life, ever turn to Vernon in the surrender of wifely affection? As I looked at the two in the bows I wondered.

But even as he thinks this, they move closer together in their sleep and, unconsciously, Vernon moves a protective arm around his woman. They will be fine. What a long, drawn-out, convoluted and outlandish farrago of a story!

P.S.

The Wikipedia summary says that: ‘In the house, Vernon had recognised the room that appeared in his dreams, and Koré as his yearly-advancing presence’ thus very neatly giving meaning to his annual nightmare – but I just read the last chapters quite carefully and didn’t notice this, slick though it would have been.

Social history

A selection of the chance, throwaway comments by the narrator which shed light on the values and ideas of the time i.e. just before and after the Great War. Often, in these old texts, I find the peripheral details more interesting than the shallow characters and preposterous plots.

Freud

Those were the days before psycho-analysis had become fashionable, but even then we had psychologists…

The Great War

My path was plain compared to that of many honest men. I was a bachelor without ties, and though I was beyond the statutory limit for service I was always pretty hard trained, and it was easy enough to get over the age difficulty. I had sufficient standing in my profession to enable me to take risks. But I am bound to say I never thought of that side. I wanted, like everybody else, to do something for England, and I wanted to do something violent. For me to stay at home and serve in some legal job would have been a thousand times harder than to go into the trenches. Like everybody else, too, I thought the war would be short, and my chief anxiety was lest I should miss the chance of fighting. I was to learn patience and perspective during four beastly years.

The post-war

He gives a vivid description of the frenetic atmosphere of 1919, young men rootless and aimless, young women desperate to capture the four lost years of fun, colliding in a world of wild parties and frantic dancing (pages 59 to 61).

He had called her tawdry and vulgar and shrill, he had thought her the ugly product of the ugly after-the-war world. (p.216)

Though Leithen doesn’t like it, regarding it as ‘a good deal of shrillness and bad form’, under the circumstances, he can understand it. In among his bad-tempered grumbling about the new world and its manners, he has an amusingly unkind word for the movie industry:

Well-born young women seemed to have taken for their models the cretinous little oddities of the film world.

A hundred years later those cretinous little oddities dominate the worlds of celebrity, fashion, merchandise and even social movements (#metoo) to an unprecedented degree.

Buchan’s racism

One night Vernon and I had been dining at the house of a cousin of mine and had stayed long enough to see the beginning of the dance that followed. As I looked on, I had a sharp impression of the change which five years had brought. This was not, like a pre-war ball, part of the ceremonial of an assured and orderly world. These people were dancing as savages danced – to get rid of or to engender excitement. Apollo had been ousted by Dionysos. The nigger in the band, who came forward now and then and sang some gibberish, was the true master of ceremonies.

Doesn’t need any comment from me.

Buchan’s antisemitism

Leithen expects to dislike Ertzberger because he is a Jewish banker:

If any one had told me that I would one day go out of my way to cultivate a little Jew financier, I would have given him the lie…

Although, in the event, he likes Ertzberger – ‘I had liked him, and found nothing of the rastaquouère in him to which Mollie objected.’ (I had to look up rastaquouère. It means: ‘A social upstart, especially from a Mediterranean or Latin American country; a smooth untrustworthy foreigner.’). But Leithen’s liking doesn’t extend to Ertzberger’s wife.

She was a large, flamboyant Belgian Jewess, a determined social climber, and a great patron of art and music, who ran a salon, and whose portraits were to be found in every exhibition of the young school of painters.

Buchan’s sexism

Is this sexist? Is it misogynist? It’s not full of hatred of women, just, maybe, rather patronising.

I once read in some book about Cleopatra that that astonishing lady owed her charm to the fact that she was the last of an ancient and disreputable race. The writer cited other cases – Mary of Scots, I think, was one. It seemed, he said, that the quality of high-coloured ancestors flowered in the ultimate child of the race into something like witchcraft. Whether they were good or evil, they laid a spell on men’s hearts. Their position, fragile and forlorn, without the wardenship of male kinsfolk, set them on a romantic pinnacle. They were more feminine and capricious than other women, but they seemed, like Viola, to be all the brothers as well as all the daughters of their father’s house, for their soft grace covered steel and fire. They were the true sorceresses of history, said my author, and sober men, not knowing why, followed blindly in their service.

It’s certainly the kind of tone and opinion you read in older (Victorian, Edwardian) criticism and essays. To me it’s a romantic fantasy as fantastical and concocted as the spirit and plot of the rest of this cooked-up fantasia.

Slim women

Buchan prefers slim women, women who are, in fact, almost indistinguishable from boys – so he approved of this aspect of post-war fashion, the skinny flappers, even if he hated their too much makeup and frenetic dancing to barbarous music.

There were several girls, all with clear skins and shorn curls, and slim, straight figures. I found myself for the first time approving the new fashion in clothes. These children looked alert and vital like pleasant boys, and I have always preferred Artemis to Aphrodite.

Hence Vernon’s first sight of Kore in the doomed House:

He saw a slim girl, who stood in the entrance poised like a runner…

And when he realises he’s falling in love with her, Vernon, characteristically for his ilk, juvenilises her even more, making her a child:

Vernon had suddenly an emotion which he had never known before—the exhilaration with which he had for years anticipated the culmination of his dream, but different in kind, nobler, less self-regarding. He felt keyed up to any enterprise, and singularly confident. There was tenderness in his mood, too, which was a thing he had rarely felt—tenderness towards this gallant child. (p.218)

Which, of course, tends to give him the feeling of being the responsible and in-control father.

Boys

Mind you, it’s not just young women who are reverted to childhood. Both Leithen and Vernon feel rejuvenated and restored to a feeling of boyish adventure by these preposterous high jinks:

All this care would have been useless had Vernon not been in the mood to carry off any enterprise. He felt the reckless audacity of a boy, an exhilaration which was almost intoxication, and the source of which he did not pause to consider. Above all he felt complete confidence. (p.222)

Civilisation and barbarism

I had a moment of grim amusement in thinking how strangely I, who since the war had seemed to be so secure and cosseted, had moved back to the razor-edge of life. (p.179)

A comment in a critical essay has alerted me to the idea that Buchan’s central notion is the dichotomy between civilisation and barbarism, and it’s certainly at the heart of this book. In his office in London Leithen is seized by a sense of unreality at the discrepancy between the mad pagan rituals he’s reading about and the everyday boredom of London traffic and tea at 4.

The opposite of civilisation is barbarism and, once settled on the island, he comes to think of the local Greek peasants as barbarians.

Here was I, a man who was reckoned pretty competent by the world, who had had a creditable record in the war, who was considered an expert at getting other people out of difficulties – and yet I was so far utterly foiled by a batch of barbarian peasants. (p.156)

What is barbarism? At its core is the intention to murder, in the case of the Greek islanders, organised, premeditated murder:

The madmen of Plakos were about to revive an ancient ritual, where the victor in a race would be entrusted with certain barbarous duties.

But it doesn’t just happen to others in remote communities – as Leithen becomes more and desperate about Koré’s safety, he himself undergoes a transformation back down the rungs of the ladder.

I was now quite alone – as much alone as Koré – and fate might soon link these lonelinesses. I had had this feeling once or twice in the war – that I was faced with something so insane that insanity was the only course for me, but I had no notion what form the insanity would take, for I still saw nothing before me but helplessness. I was determined somehow to break the barrier, regardless of the issue. Every scrap of manhood in me revolted against my futility. In that moment I became primitive man again. Even if the woman were not my woman she was of my own totem, and whatever her fate she should not meet it alone. (p.168)

The same reversion to a primitive avatar which he undergoes when he sees the Dancing Floor all decked out for the ceremony:

The place was no more the Valley of the Shadow of Life, but Life itself – a surge of daemonic energy out of the deeps of the past. It was wild and yet ordered, savage and yet sacramental, the home of an ancient knowledge which shattered for me the modern world and left me gasping like a cave-man before his mysteries.

And:

I was struggling with something which I had never known before, a mixture of fear, abasement, and a crazy desire to worship. Yes – to worship. There was that in the scene which wakened some ancient instinct, so that I felt it in me to join the votaries.

An unhallowed epiphany was looked for, but first must come the sacrifice. There was no help in the arm of flesh, and the shallow sophistication of the modern world fell from me like a useless cloak. I was back in my childhood’s faith, and wanted to be at my childhood’s prayers.

And Vernon, as he mingles with the young men about to start the sacred race, feels just the same:

He saw the ritual, which so far had been for him an antiquarian remnant, leap into a living passion. He saw what he had regarded coolly as a barbaric survival, a matter for brutish peasants, become suddenly a vital concern of his own.

In other words, not only communities of outsiders and foreigners (the Greeks in this story, the Black rebels in Prester John) can be barbarians i.e. fired up to murder the innocent and unarmed according to ancient and bloodthirsty values – but even men as calm, sedate, educated and civilised as Sir Edward Leithen or as prosaic and urbane as Vernon Milburne, can be sent reeling back through the centuries to a primitive core, reduced to a primitive man, cave man level of cognition and emotion. We are all susceptible.

English countryside

From time to time Buchan gives lyrical descriptions of the English landscape:

I had fallen in love with the English country, and it is sport that takes you close to the heart of it. Is there anything in the world like the corner of a great pasture hemmed in with smoky brown woods in an autumn twilight: or the jogging home after a good run when the moist air is quickening to frost and the wet ruts are lemon-coloured in the sunset; or a morning in November when, on some upland, the wind tosses the driven partridges like leaves over tall hedges, through the gaps of which the steel-blue horizons shine?

They remind me of Saki’s rhapsodies about the countryside in his novels, for example 1913’s When William Came except that Saki is much better at this sort of thing than Buchan.

Credit

The Dancing Floor by John Buchan was first published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1926. References are to the 1987 Penguin paperback edition.