‘You start by sinking into his arms and end up with your arms in his sink.’

(1970s feminist slogan)

‘Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970 to 1990’ does what it says on the tin and is the largest assembly of British feminist art ever gathered together in one place. It is an encyclopedia of British feminist art and activism in the 1970s and 80s, packed with images, ideas, associations, slogans, shocking stories, stimulating art works, music and voices.

Huge

‘Women in Revolt!’ is huge. It features some 600 works by over 100 women artists and (very often) women’s collectives.

The definition of ‘work of art’ is cast as wide as possible to include paintings, drawings, photographs, textiles, prints and films, but this doesn’t begin to indicate the range of the material. Each of the seven rooms (and these are often sub-divided so you end up with about 12 distinct spaces in total) contains at least one display case, sometimes two or three, each containing large amounts of documentary material on the theme of the room, and this includes posters, leaflets, pamphlets, handouts, magazines, self-help manuals and books, all with a polemical feminist theme.

As one way of surfing through the material I set out to list all the magazines featured in these cases. I ran out of puff after noting Speak Out, Foward, Outwrite, Shrew, (lots and lots of copies of) Spare Rib, Enough, Banshee (for Irish feminists), the Beaumont Bulletin, Women’s Report, Feminist Art News, Mukli, Red Rag, In Print, the GLC Women’s Committee, Socialist Woman, Power of Women, Women Now!, Edinburgh Women’s Newsletter, Glasgow Women’s Liberation Newsletter, Tayside Women’s Liberation Newsletter and so very much on – an extraordinary outpouring of voices and opinions, a nationwide, grass roots explosion of activism and organising that burst out everywhere and then snowballed…

Reading list

The exhibition is accompanied by all kinds of paraphernalia and accessories. Before you even get in there’s a room-sized space containing a big table and 7 or 8 chairs next to shelves holding 20 or 30 feminist books from or about the period. You are encouraged to take the books down, sit and read them. I liked the look of ‘The Lost Women of Rock Music‘, although maybe not at the price of £49.

On a hoarding nearby there’s a list of feminists organisations which I list at the end of this review.

The LP

There’s an old-style record player playing an LP which has been created specially for the exhibition:

There are a couple of headsets so you can sit on the bench and tap your toes to feminist hits by the likes of the Mo-Dettes, the Slits, X-Ray Spex, The Raincoats or, my favourite, The Gymslips.

Films and documentaries

The LP headphones prepare you for the fact that the exhibition includes no fewer than 27 films with a combined duration of around 7 hours! Plus 25 artworks which include audio.

These all have headphones so you can sit and listen to documentaries about black women or a BBC discussion about whether domestic work should be paid, about the Grunwick strike, a shocking documentary about how women of colour immigrating to Britain had to undergo virginity checks (in the 1970s) and so on.

Related events

The exhibition is accompanied by 6 podcasts, a long Spotify playlist of Women in Revolt music, and there’s a festival of feminist films at the National Film Theatre. The Tate café even has feminist cakes on sale.

It’s much, much more than an exhibition. It feels like a parallel universe, the universe of committed feminists which sits alongside the universe the rest of us inhabit, and yet is based on a completely different set of values and assumptions, has its own vocabulary and jargon, inhabits a discursive realm thronged with hundreds of thousands of books, pamphlets, articles, meetings, organisations, websites, social media pronunciations, an endless alternative point of view.

Start point 1970

The exhibition very specifically covers the period 1970 to 1990. Why? 1970 was the year of the first Women’s Liberation Conference and is a convenient starting point for the emergence of a distinctive feminist branch of the cultural and political rebellions of the later 1960s.

Thus the early rooms are all about squats and collectives and are liberally sprinkled with talk of overthrowing capitalism, how capitalism relies on the patriarchy i.e. the systematic oppression of women, undervaluing of women’s work (especially housework and child-rearing) and so on.

There are pamphlets explaining the communist take on women and the family (‘Feminism in the Marxist Movement’ and ‘Communism and the Family’). In the curators’ words:

In the 1970s and 1980s a new wave of feminism erupted. Women used their lived experiences to create art, from painting and photography to film and performance, to fight against injustice. This included taking a stand for reproductive rights, equal pay and race equality. This creativity helped shape a period of pivotal change for women in Britain, including the opening of the first women’s refuge and the formation of the British Black Arts Movement.

There are lots of black-and-white photos of squats and slums, some of the vintage documentaries who street scenes of road filled with lovely old motors from the 60s and 70s.

Are many women Marxists?

The wall label of room 2 states:

Many women see capitalism as the root of their oppression. They challenge its reliance on patriarchal systems in which men hold the power and women are largely excluded. They also view women’s unpaid reproductive labour as exploitation, and a necessary condition of capitalism.

Do they? Do ‘Many women see capitalism as the root of their oppression’? In the intense hothouse of academia, maybe. But out here in the wider world where many women run companies and corporations and, of course, populate the highest ranks of the Conservative Party?

The buzzwords ‘capitalism’, ‘communism’ and ‘socialism’ crop up throughout the exhibition, particularly in the earlier rooms when we’re closest in time to the revolutionary turmoil of the late 1960s and many radicals thought that Western capitalism was teetering on the brink of collapse.

This made me feel sadly nostalgic for my school days in the 1970s when left-wingers believed in such a thing as socialism, believed that capitalism could be ‘overthrown’, all it would take would be one more heave and the entire oppressive system would be overthrown and usher in the communist utopia, social ownership of utilities, industries and businesses, where everyone would contribute according to their ability and take according to their need.

The economic, social and political naivety of those times seem an age ago, now.

Nostalgia

This raises an issue I had throughout the show which is that, I think I was meant to respond with outrage and sympathy to the many oppressions women laboured under in the 1970s and 80s but I found quite a lot of the material heart-warmingly nostalgic. Take the room devoted to punk women, which featured artworks and videos (of Ludus performing) and a display case full of fanzines with Johnny Rotten or the Clash on the cover. This was pure nostalgia for me and warmed the cockles of my heart.

Art or social history?

This thought in turn triggered several other questions which nagged me all the way through, namely: 1) How much of the works on display were art and how much social history? At one end were paintings and sculptures which are explicitly and unambiguously art. At the other end were the display cases holding magazines, posters, pamphlets and whatnot which are, in my opinion, documents of social history. In between were questionable objects or works which begged the question. For example, there’s a room devoted to Greenham Common. As in every room, it has a display case showing magazines, flyers, letters, maps and so on. In complete contrast was a massive installation of a wire fences covered with bric-a-brac typical of the camp and, on another wall, a bit painting (art).

But what about the ten or so (very good) black-and-white photos showing Greenham women in various stages of protest? Are they ‘art’, or documentary shots as might be taken by a magazine journalist? Or the quilt made by several Greenham women, showing Greenham slogans, hanging on the wall?

2) And this was related to a second question which was: am I responding to the works because a) they nostalgically remind me of my misspent youth (e.g. the punk room), or b) because I’m responding to the issues they raise and the (sometimes terrible) stories they tell) or c) as works of art?

Very few of the 600 works on display actually cut through to me as works of art (I mention my favourites below). Far more of them were attached to stories which were more in the shape of newspapers stories (the police shooting of Cherry Groce, the virginity inspections of black women immigrants, the disabled woman who was sterilised by male doctors without her consent etc) or issues (abortion, social pressure on women etc).

Or had a kind of documentary factual basis such as, in the pregnancy room:

- the 90 second long black-and-white movie which consisted simply of a close-up of a pregnant woman’s stomach so that you could see the baby moving inside (Antepartum by Mary Kelly)

- the sequence of black-and-white photos a woman artist took of her stomach from the moment she learned she was pregnant

‘Ten Months’ documents Hiller’s pregnancy. The artist uses a conceptual framework to explore an intensely subjective experience, presenting one photograph of her stomach for each of the 28 days of 10 lunar months. Accompanying the photographs are texts from the artist’s journal that reflect on the psychic and physical changes that occur during pregnancy.

(Who isn’t) restoring women’s voices?

As always, the curators claim that many of these artists have been overlooked and left out of traditional male-dominated narratives of modern art – ‘women, who despite long careers, have been largely left outside the artistic narratives of the time’ – and so this exhibition is putting things to rights!

For many of the featured artists, this will be the first time many of their works have been on display since the 1970s.

This is very similar to the claim made at the ‘RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology’ exhibition which is on at the Barbican until 14 January, and which also brings together women artists and collectives from the 1980s through to the present day, also claiming they have been written out of art history, also claiming to set the record straight, also claiming to give women artists their voice, etc.

In other words, this is the standard claim made at the exhibition of almost any woman artist or artists. It may well be true. But it’s well on the way to being a cliché, one of the received ideas of our time.

Are they worth it?

I’ll come straight out and state an obvious point: maybe a lot of these women artists weren’t consciously ‘written out’ of art history by wicked white male art historians as a result of a patriarchal conspiracy, but because they…er…aren’t any good.

Take that LP featuring tracks by revolting women bands such as the Mo-Dettes, the Slits, the Poison Girls, the Gymslips, the Au Pairs, Girls At Our Best and so on…maybe these bands haven’t been forgotten by time or erased, i.e. aren’t much known or written about in histories of pop music, not as the result of some scary conspiracy by white male music critics but…because they’re just not as good or interesting as The Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Jam, The Buzzcocks et al.

Some of the work here is outstanding, but a lot of it only makes sense in the context of feminist protest, was designed to provoke the enemy or raise the consciousness of allies, to educate and inform. A lot of it is only a little step above the posters, pamphlets and handouts created by women all over the country in response to injustice and discrimination, which is to say they are all in a worthwhile cause but…as art…judged as works of art…even if we extend the definition of ‘art’ to breaking point…

Rather than rewriting them badly, here are the curators’ own wall labels quoted directly. Indentation indicates curators’ text.

Room 1. Rising with Fury

In the early 1970s, women were second-class citizens. The Equal Pay Act wouldn’t be enacted until 1975. There were no statutory maternity rights or any sex-discrimination protection in law. Married women were legal dependants of their husbands, and men had the right to have sex with their wives, with or without consent. There were no domestic violence shelters or rape crisis units. For many women, their multiple intersection identities led to further inequality. The 1965 Race Relations Act had made racial discrimination an offence but did nothing to address systematic racism. While trans women were gaining visibility, a controversial 1970 legal case found that sex assigned at birth could not be changed, setting a precedent that would impact trans lives for decades. The 1970 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act gave people with disabilities the right to equal access but failed to make discrimination unlawful. In 1967, the Sexual Offences Act had partially decriminalised sex between two men, but lesbian rights were almost entirely absent from public discourse.

In 1970, more than 500 women attended the first of a series of national women’s liberation conferences. Sally Alexander, one of the organisers notes, it was the beginning of ‘a spontaneous iconoclastic movement whose impulse and demands reached far beyond its estimated twenty thousand activists.’ Many of these activists were also members of organisations like the Gay Liberation Front (1970 to 1973) and Brixton Black Women’s Group (1973 to 1985). Together they marked a ‘second wave’ of feminist protest, emerging more than fifty years after women’s suffrage. They understood that women’s problems were political problems, caused by inequality and solved only through social change.

The artists in this room made art about their experiences and their oppression. They worked individually, and in groups, sharing resources and ideas, and using DIY techniques. Their subject matter and practices became forms of revolt, and their art became part of their activism.

Three display cases in room 1 of Women in Revolt! giving a sense of the number of small to medium-sized objects on display © Tate. Photo by Madeleine Buddo

I liked ‘Rabbits – the Pregnant Bunny Girl, Mrs Rabbits and Woman as Animal’ by Shirley Cameron.

These photographs document a performance from 1974. While heavily pregnant with her twin daughters, Cameron dressed as a Playboy bunny girl and ‘installed’ herself in a pen with rabbits at local country shows. She toured the Devon County Show, Lincoln Show, Three Counties Show, Border Show and East of England Show. Brilliant idea.

I liked the photos of a performance based on a wedding ceremony by Penny Slinger.

These photographs document a performance in which Slinger wore a handmade wedding cake costume. The artist describes the series as ‘both a parody of a wedding ritual, and recreation from a woman’s point of view’. The images were included in Slinger’s 1973 solo show at Flowers Gallery, London. Deemed too controversial for public display, the police raided and shut down the exhibition shortly after it opened.

Near the top of my favourite pieces in the show was a series of three porcelain figures of dancers by Rose English. These are small, barely a foot tall, brightly and joyfully decorated, humorously emphasising each figures’ brightly coloured vulva and melony breasts. They were fun and innocently frank.

Porcelain Dancer 1 by Rose English © Rose English courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London and Rome. Photo by the author

Room 2. The Marxist wife still does all the housework

By the mid-1970s, women has asserted their rights to equal pay and to work free from discrimination and harassment. Some held positions of power in business and politics, and following Margaret Thatcher’s election as prime minister in 1979, a woman held the highest office in the country. Despite this, traditional gender roles remained. For women to achieve equality, change was needed in both public and private spheres.

Small consciousness-raising groups brought women together to discuss their shared experiences and recognise the social and political causes of their inequality. This practice woke women up to their oppression and made the personal political. Women discussed the concept of reproductive labour – the work required to sustain human life and raise future generations – and joined international campaigns such as Wages for Housework. Art became a tool to highlight the unpaid activities they were expected to perform and the physical and emotional impact this had on them.

For many women artists, there was no separation between their home life and artistic practice. They produced work at kitchen tables between caring and domestic responsibilities. Their environment informed the materials used, the size and format of their work, as well as their subject matter. Artists also turned to their bodies as their subjects. They explored fertility, reproduction and the complexity of navigating highly prejudicial medical systems, particularly for women with multiple intersecting identities.

The artists in this room challenge art historical tropes and media stereotypes: from the idealised nude to the selfless mother and doting housewife. These women present their bodies and homes as sites of oppression whilst simultaneously reclaiming agency over them.

Three fabulous crocheted figures by Rita McGurn

McGurn worked as a television, film and interior designer. In the 1970s and 1980s her art practice was pursued privately, primarily in the context of her home. She employed a range of found and domestic materials in her practice, making use of whatever was to hand. Working in crochet, she created life-sized people that were placed around the house in changing configurations. Her daughter, artist France-Lise McGurn (born 1983) recalls, ‘We all lost some good jumpers to those crochet figures, as stuffing or just stitched right in.’

Screaming video by Gina Birch

Birch writes: ‘I came to London from Nottingham in 1976 to go to Hornsey College of Art. I was very soon immersed in what became punk and the world of 1970s politics of squatting, nuclear disarmament, Rock Against Racism and later Rock Against Sexism. The rundown city was our playground.’ At Hornsey, she met Ana da Silva and they formed the experimental punk band The Raincoats (as featured on the exhibition LP). Birch recalls, ‘It was a time of casual sexism, casual sex and more overt sexism.’ Three-minutes is the approximate length of a Super 8 film cartridge, here filled entirely with Birch’s energetic screaming.

Helen Chadwick

This was really good, 12 photos recording a performance given by Chadwick, titled ‘In the Kitchen’. What I liked very much about them was their geometric precision and symmetry. Plus the brilliance of the conception.

For this performance Chadwick created wearable sculptural objects from PVC ‘skins’ stretched over metal frames. They included a cooker, sink, refrigerator, washing machine and cupboards. The original setting featured a strip of vinyl floor tiles and a soundtrack of excerpts from the BBC Radio 4 programmes ‘Woman’s Hour’ and ‘You and Yours’. Chadwick wrote: ‘The kitchen must inevitably be seen as the archetypal female domain where the fetishism of the kitchen appliance reigns supreme. By highlighting and manipulating this familiar domestic milieu, I have attempted to express the conflict that exists between … the manufactured consumer ideal/physical reality, plastic glamour images/banal routine, conditioned role-playing/individuality.’

‘In the Kitchen (Stove)’ by Helen Chadwick (1977) © The Estate of the Artist. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London and Rome

Erin Pizzey

An honourable mention for Erin Pizzey who in 1971 founded the Chiswick refuge for abused women (formally known as Chiswick Women’s Aid), a self-funded haven for women victims of domestic abuse, and a model which was to be copied first around the country and then across the world.

It’s recorded here in six highly evocative black-and-white documentary photos. A nearby display case contains a copy of the book Pizzey wrote on the subject, ‘Scream quietly or the neighbours will hear.’ What a heroine, what a heroic achievement – although, reading further about her life, you see that Pizzey, like so many other idealistic feminists from the 1960s and 70s, has had a tortuous and often disillusioning afterlife.

Room 3. Oh bondage, up yours! (i.e. punk feminism)

Subcultures provided opportunities for new models of womanhood from the mid-1970s. Punk, post-punk and alternative music scenes combined socially conscious, anti-authoritarian ideologies with DIY methods. Technical virtuosity was out, and the amateur was in. Freed from the pressure of being the best, the first, or the most original, artists began trashing the conventions of both high and popular culture, giving rise to new forms of expression.

Young musicians, artists, designers and writers set up bands, record labels, fanzines, collectives and club nights. They created work that pushed the boundaries of acceptability, often using clashing and violent imagery and explicit material. For many women this meant subverting gender norms, embracing the provocatively ‘unfeminine’ as well as the hypersexual.

Through their DIY methods, multi-disciplinary approaches and challenge to the status quo, these subcultures had much in common with the women’s movement. Yet artist and musician Cosey Fanni Tutti notes: ‘I aligned myself more with Gay Liberation than Women’s Liberation… Freedom “to be” was my thing. I didn’t want another set of rules imposed on me by having to be “a feminist”.’ For zine writer and punk feminist Lucy Whitman (then Lucy Toothpaste), it didn’t matter whether these women identified as feminists or not, ‘in all their lyrics, in their clothing, in their attitudes – they were challenging conventional attitudes’. These artists were freeing women of the bondage of expectation and helping them redefine women’s role in society.

Leotard (1979) by Cosey Fanni Tutti

This is an example of one of the costumes worn by Fanni Tutti for her professional striptease performances. The artist explains: ‘The costumes I used for my striptease work were “scripted” according to the audiences I performed to. Each signed a different masked persona, a fantasy or sexual predilection applicable to the age or social groups of the men who frequented the places I performed in. The vast majority of the costumes were made myself using carefully selected sensual practical materials that enabled smooth, elegant removal.’

Gill Posener’s defaced posters

You see these around quite a lot but they never lose their sparkle:

Installation view of photos of posters defaced by Gill Posener in 1982 and 1983. Photo by the author

In these prints Posener documents a series of feminist interventions to advertising billboards around London. Living in lesbian squats in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Posener and her friends (who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution) would graffiti over sexist billboards and photograph them. Prints were sold as postcards to raise funds for radical causes. After moving to the US in the late 1980s, Posener became photo editor of the hugely influential lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs.

Room 4. Greenham Common

There’s a room about Greenham Common at the Barbican Re/Sisters exhibition. There was a room about Greenham at the Imperial War Museum’s exhibition about war protests a few years ago. I.e. it’s all true, it was all worthwhile but, in the realm of culture, it’s a well-trodden cliché.

On 5 September 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to the Royal Air Force base at Greenham in Berkshire. They called themselves Women for Life on Earth. They were challenging the decision to house 96 nuclear missiles at the site. When their request to debate was ignored, they set up camp. Others joined, creating a women-only space. Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp became a site of protest and home to thousands of women. Some stayed for months, others for years, and many (including a great number of artists in this exhibition) visited multiple times.

Greenham women saw their anti-nuclear position as a feminist one. They understood that government spending on nuclear missiles meant less money for public services. They used their identities as mothers and carers to fight for the protection of future generations and a more equal society. The camp’s way of life – communal living, no running water, regular evictions and arrests – was challenging. But Greenham was also a refuge. Women were liberated from the restrictions of heteronormative society and embraced separatism. Race, class, sexuality and gender roles were regular topics of discussion.

Protest took on artistic forms for Greenham women. They made banners and collages, produced sculptures and newsletters, and weaved spider webs of wool around the perimeter fences. They wrote and sang protest songs and keened – wailing in grief to mourn lives lost to future nuclear wars. Large-scale public actions, like the 14-mile human chain created by 30,000 people holding hands to ‘embrace the base’ brought widespread media coverage to their cause.

Greenham politicised a generation of women, inspiring protests across the world. It also forged relationships and networks that continue to inform the women’s movement.

Dominating the Greenham room is this big installation by Margaret Harrison.

Installation view of ‘Greenham Common (Common reflections) 1989 to 2013’ by Margaret Harrison. Photo by Larina Fernandes

‘Greenham Common (Common reflections) 1989 to 2013’ is constructed from concrete, mirrors, clothes, children’s boots, pram, soft toys, photographs, plastic bags, household items, wire netting and barbed wire. In this installation Harrison recreates a portion of the perimeter fence at Greenham Common military base. Women living at the Greenham Peace Camp regularly attached clothes, banners, toys, photographs, household items and other everyday objects to the wire fence Here, Harrison adds mirrors in reference to the 1983 ‘Reflect the Base’ action when women held up mirrors to allow the base to symbolically look back at itself and its actions.

Room 5. Women of colour

The following two rooms highlight some of the artists that defined Black feminist art practice in the UK. These women were part of the British Black Arts Movement, founded in the early 1980s. Their artworks explore the intersections of race, gender and sexuality. They do not share a unified aesthetic but acknowledge shared experiences of racism and discrimination.

In the 1980s, a series of high-profile uprisings across the UK highlighted the reality of life for Black people. In the face of high unemployment, hostile media, police brutality and violence and intimidation by far-right groups, people of colour came together. The term ‘political blackness’ was used to acknowledge solidarity between those who faced discrimination based on their skin colour. Many artists drew on this collective approach. They formed networks, organised conferences and curated exhibitions in order to navigate institutional racism in the art world. As Sutapa Biswas and Marlene Smith described in 1988:

We have to work simultaneously on many different fronts.

We must make our images, organise exhibitions, be art critics, historians, administrators, and speakers. We must be the watchdogs of art establishment bureaucracies; sitting as individuals on various panels, as a means of ensuring that Black people are not overlooked.

The list is endless.

In 1981, Bhajan Hunjan and Chila Kumari Singh Burman opened Four Indian Women Artists, the first UK exhibition exclusively organised by and featuring women of colour. In the following years artists including Sutapa Biswas, Lubaina Himid, Rita Keegan and Symrath Patti curated group exhibitions that set out to challenge what Himid describes as the double negation of being Black and a woman. By working, organising and exhibiting together, women of colour developed personal and professional networks that helped them sustain their practices up to the present day.

There’s a lot in these rooms. I liked a very conventional but beautifully executed painting, ‘Woman with earring’ by Claudette Johnson, which you can see on Pinterest.

Also a video by Mona Hatoum in which she walked through Brixton barefoot with her ankles attached to Doctor Marten boots which seem to have been filled with weights to make each step a challenge. Irritatingly, I can’t find the video online, but there’s a Tate web page about it.

Love, Sex and Romance by Rita Keegan

‘Love, Sex and Romance’ consists of 12 vivid photocopies and screenprints on paper.

Keegan’s work responds to her extensive family archive that dates back to the 1880s. Here, Keegan employs images and fragments from this archive to create monoprint collages. The artist describes her practice as a response to ‘a feminist perspective’ of ‘putting yourself in the picture’. In talking about her process, Keegan explains: ‘I’ve always felt that to tear somebody’s face can be quite violent, but if you’re doing that to your own face, you’ve given yourself permission, so it’s no longer a violent act. It’s a deconstructive act. It’s a way of looking.’ This work was made in 1984, the same year Keegan co-founded Copy Art, a community space for artists working with computers and photocopiers.

Room 6. ‘There’s no such thing as society’ [the AIDS, gay and lesbian room]

In 1987, weekly lifestyle magazine Women’s Own interviewed Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. She discussed AIDS, the importance of the ‘traditional family’, and money as ‘the driving force of life’. During the interview she delivered the infamous line, ‘there is no such thing as society’

Thatcher’s statement centred the ‘individual’ and reflected her ‘fundamental belief in personal responsibility and choice’. This position aligned with her neoliberal ideology, encouraging minimal state intervention in economic and social affairs. Thatcher’s opponents read her comments as a suggestion people could overcome the conditions of their oppression through hard work and resolve. This failure to acknowledge the social and systemic inequalities that led to this oppression was counter to everything women’s liberation stood for.

The free market agenda of Thatcher’s Conservative government had also brought about a shift in the art world. Alongside the rapid commercialisation of the art market, a series of cuts to state funding resulted in arts organisations turning to corporate sponsorship. For the artists in this exhibition, this focus on individualism and profitability made the challenge of finding funding, space or a market for their work even harder.

Yet these artists persisted. They continued to make art, question authority and challenge dominant narratives. Times were difficult but they rose to the occasion. As Ingrid Pollard notes: ‘We weren’t expecting to get exhibitions at the Tate; in the 1980s, people set up things of their own. We did shows in alternative spaces – community centres, cafes, libraries, our homes. We occupied spaces differently.’

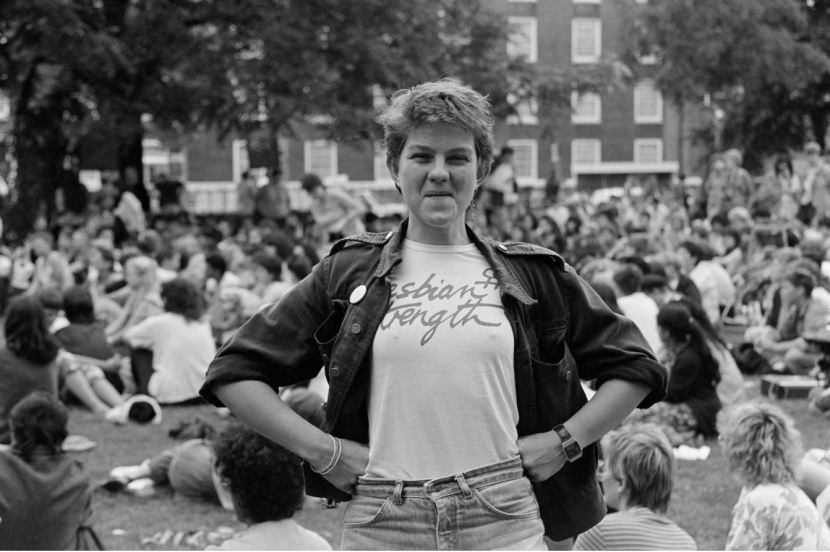

Gays and lesbians interviewed on film, playing on TV monitors. Photos of lesbians frolicking in the woods, on marches, staging poses for arty photos.

There’s a humorous slogan on one of the photos (the exhibition is awash with ‘radical’ slogans, mottos, t-shirt jingles, lapel badge phrases and so on; before you even enter the exhibition, in the book space I mentioned there’s an entire wall of lapel badges each with a smart, catchy slogan).

One of these days these dykes are going to walk all over you.

Disability arts

The gay and lesbian room morphs into an area devoted to activist art for the disabled. For some reason these tugged at my heartstrings more than a lot of the art from the previous rooms. A society, and maybe all of us as individuals, will be judged by how we treat the weakest and most vulnerable in our society. If there is a God, they will judge us not by how angry we get at each other on Twitter or TikTok but how kind we are, especially to the poorest and weakest in our societies. It’s worth setting down the curators’ summary of disability arts, much less publicised than feminist art.

The Disability Arts Movement played an important part in the political struggle for Disability Rights and the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act. Artists and activists worked together to fight marginalisation and create more authentic representations of disabled people. Organisations such as Shape (founded 1976), Arts Integrated Merseyside (now DaDAFest) (founded 1984), London Disability Arts Forum (founded 1986) and publications such as Disability Arts in London (DAIL) (first published 1985) promoted Disability Arts across the UK.

Women were engaged with this work from the outset. In 1985, photographer Samena Rana spoke on disability and photography as part of Black Arts Forum Weekend at the ICA, London. In 1988 artist Nancy Willis was joint organiser of the Disabled Women Artists Conference at the Women Artists’ Slide Library in London. In 1989, DAIL editor Elspeth Morris guest edited an edition of Feminist Art News titled ‘Disability Arts: The Real Missing Culture’. The publication featured 18 contributors including standup comic Barbara Lisicki who declared, ‘I’m a disabled woman. My existence has been mocked, scorned and misrepresented and by being up here I’m not allowing that to continue.’

End point

The curators have chosen 1990 as the end point of the exhibition though there is no one event to mark it as clearly and definitively as the 1970s women’s liberation conference which marked the start. In November that year Mrs Thatcher was forced to resign. The Soviet Union was to cease to exist the following year. The downfall of Thatcher supposedly led to a more moderate form of Conservatism under John Major, though I was there and it seemed, at the time, more like a long, drawn-out epoch of embarrassing Tory incompetence. Around the same time (1989 to 1991) the collapse of the Soviet Union evaporated faith in a communist alternative to Western capitalism which had sustained the radical left for the previous 70 years. Much of the fiery left-wing rhetoric of the previous decades was suddenly hollowed out, became irrelevant overnight.

A bit more interestingly, in the wall label for the final room the curators claim that it was the growing influence of the commercial art market which led to the marginalisation of the kind of hand-made, self-grown, radical, agit-prop art we’ve just been soaking ourselves in. In the 1990s art began its journey of increasingly commercialisation and monetisation which has brought us to the present moment when Damien Hirst artworks regularly sell for tens of millions of dollars.

My memory is that, as the 1990s progressed, the economic and cultural legacy of the Thatcher years kicked in, became widely accepted, became the foundational values of more and more people – and that ‘art’ became more and more about money and image. I loved the 1997 ‘Sensation’ exhibition but recognised at the time that it symbolised the triumph of the values of its sponsor, Charles Saatchi, the sensational, newsworthy but superficial values of a phenomenally successful advertising executive.

A lot of the material in this huge exhibition is barely art at all, or is art which relies heavily on its polemical political message for its value – but I miss the era when feminists like these, when so many of us on the left, believed that genuine society-wide change was possible. I take the mickey out of it but I miss it, too.

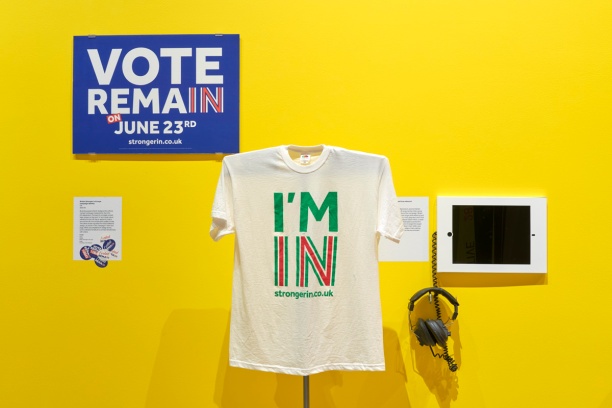

The merch

After visiting an exhibition stuffed with calls to overthrow capitalism, overthrow the patriarchy, overthrow the system which exploits women etc it’s always comical to emerge into the exhibition shop and discover you can buy all sorts of classy merchandise designed to help you overthrow capitalism from the comfort of your own living room.

Alongside the posters, prints, fridge magnets and tote bags festooned with slogans about women uniting and overthrowing the patriarchy, even I was surprised to come across a stand of feminist beer.

This is Riot Grrrl Pale Ale, retailing at the revolutionary price of £7.95 a can – according to its marketers, ‘a tropical pale ale that’s as bold and rebellious as the feminist music, art and activism it champions.’

A long, long time ago (1978) The Clash lamented how the system turns rebellion into money. Countless works and slogans from the exhibition will probably inspire women who visit it to keep the torch burning, to take forward the endless struggle of women fighting for equality. But I humbly suggest that not many women nowadays believe they can ‘overthrow capitalism’ and so they, like most of us, have to make the best accommodations we can to the system as it actually is.

List of artists

Brenda Agard; Sam Ainsley; Simone Alexander; Bobby Baker; Anne Bean; Zarina Bhimji; Gina Birch; Sutapa Biswas; Tessa Boffin; Sonia Boyce; Chila Kumari Singh Burman; Shirley Cameron; Thalia Campbell; Helen Chadwick; Jennifer Comrie; Judy Clark; Caroline Coon; Eileen Cooper; Stella Dadzie; Poulomi Desai; Vivienne Dick; Nina Edge; Marianne Elliott-Said (Poly Styrene); Rose English; Catherine Elwes; Cosey Fanni Tutti; Aileen Ferriday; Format Photographers Agency; Chandan Fraser; Melanie Friend; Carole Gibbons; Penny Goring; Joy Gregory; Hackney Flashers; Margaret Harrison; Mona Hatoum; Susan Hiller; Lubaina Himid; Amanda Holiday; Bhajan Hunjan; Alexis Hunter; Kay Fido Hunt; Janis K. Jefferies; Claudette Johnson; Mumtaz Karimjee; Tina Keane; Rita Keegan; Mary Kelly; Rose Finn-Kelcey; Roshini Kempadoo; Sandra Lahire; Lenthall Road Workshop; Linder; Loraine Leeson; Alison Lloyd; Rosy Martin; Rita McGurn; Ramona Metcalfe; Jacqueline Morreau; The Neo Naturists; Lai Ngan Walsh; Houria Niati; Annabel Nicolson; Ruth Novaczek; Hannah O’Shea; Pratibha Parmar; Symrath Patti; Ingrid Pollard; Jill Posener; Elizabeth Radcliffe; Franki Raffles; Samena Rana; Su Richardson; Liz Rideal; Robina Rose; Monica Ross; Erica Rutherford; Maureen Scott; Lesley Sanderson; See Red Women’s Workshop; Gurminder Sikand; Sister Seven; Monica Sjöö; Veronica Slater; Penny Slinger; Marlene Smith; Maud Sulter; Jo Spence; Suzan Swale; Anne Tallentire; Shanti Thomas; Martine Thoquenne; Gee Vaucher; Suzy Varty, Christine Voge; Del LaGrace Volcano; Kate Walker; Jill Westwood; Nancy Willis; Christine Wilkinson; Vera Productions, Shirley Verhoeven.

Promotional video

Information and support

- Fertility Network UK

- Gendered Intelligence

- London Black Women’s Project

- MSI Reproductive Choices

- Rape Crisis

- National Self Harm Network

- Pregnant then Screwed

- Refuge

- Scope

- Switchboard

- Terence Higgins Trust

- Trades Union Congress

Research and resources

- Bishopsgate Institute Special Collections and Archives

- Black Cultural Archives

- Cinenova

- Feminist Archive North

- Feminist Archive South

- The Feminist Library

- Glasgow Women’s Library

- LUX

- National Disability Arts Collection and Archive

- Panchayat Collection

- The Women’s Art Library

Related links

- Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970 to 1990 continues at Tate Britain until 7 April 2024

- Exhibition guide

- All the wall labels (pdf)

- Women in Revolt! podcasts

- Women in Revolt! Spotify playlist

- Women in Revolt! Film Programme