This is a huge, stunning, world-bestriding exhibition of some 250 photographs (and some films and video installations) on the subject of women and the environment, a wide-ranging survey of the multiple ways the planet is being exploited and degraded, how women too often bearing the brunt of environmental destruction, and the scores of ways women artists and activists are fighting back. At least that’s the exhibition’s aim.

A review in six parts

My review is in six parts. In part one I summarise the hyper-feminist premises or assumptions which underlie this very text-heavy and theory-driven exhibition.

In part two I give a selection of some of the feminist theory and critical theory keywords which abound in the wall captions and which were new to me.

In part three I go through the exhibition itself, quoting in full the wall labels for the introduction and the six themes or categories into which the exhibition is divided, to give you a good flavour of the text-heavy, theory-rich discourse surrounding it. Under each theme I show one or two works from that section, mostly photographs, accompanied by the complete wall caption for the relevant artist and work.

My aim is to show not only how text-heavy the show is but also how parti pris, propagandist and chauvinist the curators’ commentary is. ‘Parti pris’ means ‘preconceived, prejudiced or biased’. ‘Chauvinist’ means ‘displaying excessive or prejudiced support for one’s own cause or group’. This may sound unfair or itself biased as you read it here, which is why I’m going to quote the curators at such length, to back up this opinion and so you can judge for yourself.

Part four lists all the participating artists a) for your information and b) to show that, despite the curators’ fine words about empowering artists from the developing world or Indigenous communities, a full 40% of the artists on display are, of course, from America, home of rapacious capitalism, international finance, the biggest industrial-capitalist complex in the world, and proud birthplace of Donald Trump. So the show has a kind of inbuilt irony between its radical aspirations for diversity, and its all-too-familiar reliance on American voices and perspectives.

Part five briefly mentions some of the other recent big art exhibitions on the subject of the environment, global warming etc, as a comparison.

Part six gives my own responses, to the subject of eco-activism, to the art works and to the feminist discourse which dominates the exhibition. I wouldn’t blame you if you skip this bit. I’m not sure how much of it I myself fully believe. I spoke to two strangers at the exhibition and both of them were finding it as challenging to process the sheer amount of information, the range of issues, and the fiercely feminist perspective of the exhibition, as I was.

Why the extensive quotes

The sweeping generalisations in part one are as much as possible based on the curators’ own words. They may seem extreme or satirical to begin with but: a) I base the summary on quotes from the exhibition press release or wall labels or catalogue and have indicated quotations by single speech marks; and b) as you read on into the section quoting all the wall labels, I hope you’ll see that wild though they at first seem, they simply reflect the spirit and rhetoric of the show.

This is one of the most text-heavy exhibitions I’ve ever been to. There are six themes or categories and about 50 artists, each of whom gets a long explanatory wall caption and then additional ones for many of the works. There are maybe 80 wordy captions in total.

Not only that, but the captions come straight out of contemporary feminist and critical theory and are dense with jargon, using terms I’d never come across before (which is why I select some of these terms for consideration in part 2).

The sheer number and length of the captions means that if you read all them (as I did) Re/Sisters is like being trapped inside a book, a degree-level textbook on feminist theory, ecofeminism and post-colonial theory. I had to take a ten-minute break after doing the ground floor before going up to the first floor rooms because my brain was reeling.

I’m going to quote the introductions to each of the six sections in full to give you a sense of a) how long they are and b) how densely laden with the assumptions and jargon of feminist and critical theory.

And I’m question lots of it. Just because it’s written on a gallery wall doesn’t mean it can’t be pondered, questioned and, sometimes, rejected.

Part 1. The feminist premises of the exhibition

In the feminist discourse of this exhibition all women are fabulous. All women are creative. All women have an instinctive feel for nature and mother earth. All women are nurturing and caring and so, obviously, all women are environmentalists. No women drive cars, fly in planes, buy wasteful consumer goods or run companies and corporations which contribute to pollution and ecocide. No woman is responsible for in any way harming any part of the environment. Only men do any of these wicked things, only men run ‘the mechanical, patriarchal order that is organised around the exploitation of natural resources’ and deploy the ‘masculine cultural imperialism’ that underpins it.

‘Terms such as Capitalocene, Plantationocene and Anthropocene act as cultural-geological markers that make clear that the violent abuses inflicted upon our ecological processes are inherently gendered, and shine a light on the toxic combination of globalised corporate hegemony and destructive masculinities that characterise the age of capitalism.’ (Catalogue page 16)

‘The violent abuses inflicted upon our ecological processes are inherently gendered’ and that gender is male.

Men are not only destroying the planet but, in the process, oppressing all women everywhere and all Indigenous peoples everywhere, via ‘the oppression of “othered” bodies’. There is a direct link between men’s degradation of the planet and men’s oppression of women and men’s oppression of Indigenous societies.

Battling against oppressive men and their destruction of the planet are brave women activists and artists all around the world. They practice ‘a radical and intersectional brand of eco-feminism that is diverse, inclusive, and decolonial’. They celebrate the fact that merely by being born a woman means you are morally, spiritually and environmentally superior.

This exhibition, ‘RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology’, celebrates the women (or gender non-conforming) artists and the women activists who are fighting against male oppression and male capitalism, against the cis-heteronormative patriarchy, against masculinist capitalism, against phallogocentrism to save the planet.

RE/SISTERS brings together 50 international female (and gender non-conforming) artists to ‘show how women are regularly at the forefront of advocating and caring for the planet’.

The curators claim that environmental and gender justice are indivisible parts of a global struggle for equality and justice. Art exhibitions can ‘address existing power structures that threaten our increasingly precarious ecosystem’.

Shanay Jhaveri, Head of Visual Arts at the Barbican, is quoted as saying:

‘In this era of deepening ecological crisis, we are proud to present RE/SISTERS which interrogates the disproportionate detrimental effects of extractive capitalism on women and in particular Global Majority groups.’

In other words, the planet is being destroyed – women and minorities suffer most.

So the exhibition includes not just women but artists from ‘the Global Majority and Indigenous peoples’ because these peoples are even more intrinsically sympathetic to the environment than women are, and even more the victims of heteropatriarchal global capitalism. Including Indigenous peoples in this way offers ‘a vision of an equitable society wherein people and planet alike are venerated and treated fairly’.

It’s usually about this point in the press release that you learn that the exhibition was sponsored by BP or the Sackler family and burst out laughing. Not this time. Big art galleries have finally cleaned up their acts. This exhibition was sponsored by environmentally-friendly companies such as the Vestiaire Collective:

‘Our mission is to transform the fashion industry for a more sustainable future. As the world’s first B Corp fashion resale platform, we champion the circular fashion movement as an alternative to overproduction, overconsumption and the wasteful practices of the fashion industry. Our philosophy is simple: Long Live Fashion.’

And the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, which sponsors the Frankenthaler Climate Initiative (FCI). In the gallery bookshop there’s a space where you can donate your ‘pre-loved’ clothing to the Vestiaire Collective.

Part 2. New words

Here’s some quotes from the exhibition catalogue to get you in the zone, and also so you can check how up-to-speed you are with the latest terminology from feminist, eco-feminist, post-colonial and critical theory.

The infrastructural gaze, as in:

‘[Sim Chi Yin’s] works juxataposes the aestheticisation of the “infrastructural gaze” with the human gaze’.

Heteropatriarchal, as in:

‘Operating at the nexus of race, gender, urban ecological infrastructure, systemic injustice, environmental racism and heteropatriarchal capitalism, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s striking series “Flint is Family” exposes the segregation and racism that persists in the contemporary American landscape.’

Or:

‘In stark contrast to the received dualistic, heteropatriarchal value system of the Global North that views nature and culture as fundamentally opposed ways of being, Caycedo’s work advocates an interspecies politics that recognises nature as having agency.’

The heteropatriarchal gaze, as in:

‘Directly refuting the freighted position that men are producers of culture and that women are synonymous with nature and are therefore objects, subjects and products to be dominated by the heteropatriarchal gaze, Kruger’s searing, defiant and radical work opens our eyes and minds to the possibility of a third way, a new mode of being in our womanist bodies, freed from the shackles of masculine cultural imperialism while embracing non-separability from our ecological community.’

Cis-heteropatriarchal, as in:

‘Today, with climate catastrophe breathing ever more oppressively down our necks (egged on, of course, by the murderous white-supremacist, colonial and cis-heteropatriarchal systems that are its enablers), dealing with these questions seems all the more pressing.’

Other-than-human as an adjectival phrase as in ‘other-than-human entities’, ‘other-than-human organisms’, ‘other-than-human habitats’, ‘other-than-human communities’ and so on.

Raced, as in:

‘Understanding the body as situated, raced, gendered and sexed is not a novel idea, but the muscular geographies of petropolitics, and the populist narratives of masculinity and extraction, are rarely attended to as subjective geosocial practices that need to be undone before new earth geographies can take hold.’

Or:

‘As Esperanza makes clear, exploitation within these geophysics of extraction is intersectional, that is, it is raced and gendered. In the mine, race and gender intersect as a stratigraphic relation that becomes a mode of governance.’

Extractivism, as in:

‘These interventions gesture towards a broader understanding of how extraction – rather than extractivism, which becomes a specifically geologically-inflected formation – functions as an ideological undercurrent to colonial dispossession, racial subjection and gendered violence.’

Or:

‘I am, first, reminded not to draw easy – and, as [curator Lindsay] Nixon emphasises, colonising – equivalences between Indigenous women’s and nonbinary people’s struggles for land and life, and the movements that have expressed, in various ways, my own situated feminist and queer opposition to capitalism, colonialism, militarism and extractivism, which began in the 1980s and continues, albeit in much-changed form, into the present.’

Masculinism, as in:

‘Ecofeminist scholars have long critiqued feminised constructions of “nature” while challenging patriarchy, the masculinism of capitalism, and colonial abuses against nature, women and marginalised communities.’

Phallogocentric as in:

‘Caycedo’s photographs of rivers and waterfalls are remixed into pulsating, fractal, perception-shifting images that invite the viewer to reflect on the fluidity of bodies of water, which consistently resist the phallogocentric logic of extraction.’

Speciesism, as in:

‘As Greta Gaard notes: “Most provocative is her [Carolyn Merchant]’s intersectional linkage of racism, speciesism, sexism, colonialism, capitalism, and the mechanistic model of science–nature via the historical co-occurrence of the racist and colonialist “voyages of discovery” that resulted in appropriating indigenous peoples, animals, and land.’

Survivance, as in:

‘[Zina Saro-Wiwa] asks complex questions about Ogoni survivance that are unique to the people and place and that resist incorporation into Eurowestern narratives of environmental and climate politics.’

Eurowestern, as in:

‘Extraction as abstraction works as a representational genre precisely because within a Eurowestern context we are visually trained in the colonial (then modernist) optics that present a disembodied, planimetric view from above.

Or:

‘In this same light, then, I must also make a clear distinction between the works in RE/SISTERS that echo and amplify the Chipko women’s embodied protests as part of a contemporary network of Indigenous feminist and nonbinary activisms, and a framework emerging from more current Eurowestern discursive formations that might fold these embodied actions into queer, trans or even multispecies feminist ecological projects.’

Positionality, as in:

‘This view demands of Eurowestern environmentalists, including ecofeminists, a deep reckoning with our own positionalities, philosophies and politics.’

Part 3. The exhibition

- features about 250 works by 50 artists

- includes work from emerging and established artists in the specific fields of photography, film and installation

- after an initial introduction, is organised into six categories or themes

Introduction

‘RE/SISTERS surveys the relationship between gender and ecology to highlight the systemic links between the oppression of women and Black, trans and Indigenous communities, and the degradation of the planet. It comes at a time when gendered and racialised bodies are bending and mutating under the stresses and strains of planetary toxicity, rampant deforestation, species extinction, the privatisation of our common wealth, and the colonisation of the deep seas. RE/SISTERS shines a light on these harmful activities and underscores how, since the late 1960s, women and gender-nonconforming artists have resisted and protested the destruction of life on earth by recognising their planetary interconnectedness.

‘Emerging in the 1970s and 1980s, ecofeminism joined the dots between the intertwined oppressions of sexism, racism, colonialism, capitalism, and a relationship with nature shaped by science. Ecofeminist scholars have long critiqued feminised constructions of ‘nature’ while challenging patriarchal and colonial abuses against our planet, women and marginalised communities. Increasingly, feminist theorists recognise that there can be no gender justice without environmental justice, and ecofeminism is being reclaimed as a unifying platform that all women can rally behind.

‘Uniting film and photography by over 50 women and gender-nonconforming artists from across different decades, geographies, and aesthetic strategies, the exhibition reveals how a woman-centred vision of nature has been replaced by a mechanistic, patriarchal order organised around the exploitation of natural resources, alongside work of an activist nature that underscores how women are often at the forefront of advocating for and maintaining our shared earth.

‘Exploring the connections between gender and environmental justice as indivisible parts of a global struggle to address the power structures that threaten our ecosphere, the exhibition addresses the violent politics of extraction, creative acts of protest and resistance, the labour of ecological care, the entangled relationship between bodies and land, environmental racism and exclusion, and queerness and fluidity in the face of rigid social structures and hierarchies. Ultimately, RE/SISTERS acknowledges that women and other oppressed communities are at the core of these battlegrounds, not only as victims of dispossession, but also as comrades, as protagonists of the resistance.’

This is the first work in the exhibition:

Untitled (We won’t play nature to your culture) by Barbara Kruger

‘In Barbara Kruger’s seminal work “Untitled (We won’t play nature to your culture)” a close-cropped image, likely culled from a 1950s fashion magazine, shows a glamorous white woman lying against a grassy background with her eyes gently covered by leaves, entangling woman and nature in a symbiotic whole. With the woman’s face sandwiched between the title’s liberatory feminist message, which serves as a jarring reminder of women’s historical role in society, the work signals how women have been straitjacketed in the West by reductive Cartesian dualisms and dichotomies – culture/nature, male/female, mind/body – and a hierarchically ordered worldview. Directly refuting the freighted position that men are producers of culture and women are synonymous with nature and are therefore objects, subjects and products to be dominated by the heteropatriarchal gaze, Kruger’s searing, defiant and radical work opens our eyes and minds to the possibility of a third way, a new mode of being in our womanist bodies, freed from the shackles of masculine cultural imperialism while embracing non-separability from our ecological community.’

Untitled (We won’t play nature to your culture) by Barbara Kruger (1983) Courtesy of Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland

Theme 1. Extractive Economies / Exploding Ecologies

‘Extractivism is the exploitation, removal or exhaustion of natural resources on a massive scale. Rural, coastal, riverine, and Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by mining and other extractive industries, resulting in severe negative consequences on local livelihoods, community cohesion and the environment. Women often face the worst impacts of a violent politics of such practices, and yet they are leading the resistance against extractivism and stepping outside of traditional gender roles to champion movements fighting these destructive tendencies.

‘Over the past century rivers, forests, deserts and other natural environments have been subject to multiple forms of extraction, domestication, enclosure, erasure and pollution on an unprecedented global scale. This has entailed the profound transformation of the flow of rivers and the disappearance of once lush, fertile land, raising questions about ecological justice for the communities that rely on these environments.

‘Through their work Carolina Caycedo, Sim Chi Yin, Mabe Bethonico, and Talo Havini survey the material impact of extractive activities on rivers and dams, from Colombia to Vietnam, that support both human and more-than-human life in their nourishing embrace.

‘Meanwhile Simryn Gill, Otobong Nkanga, Chloe Dewy Matthews, and Mary Mattingly investigate the effects of industrial scale mining on landscapes and communities, from Australia to Namibia. Ultimately the works gathered here consider how extractivism operates as a material process underpinned by a pervasive colonial-capitalist mindset towards the exploitation of disempowered bodies and land.’

From the series Caspian: The Elements by Chloe Dewe Matthews (2010)

‘From images of bodies coated in the prized, thick brown crude oil found in the semi-desert region of Azerbaijan, to worshippers on pilgrimage to Shakpak-Ata, believed to have been home to a goddess of fertility and womanhood, Chloe Dewe Matthews’s photographs of the countries that border the Caspian Sea bear witness to the sticky entanglement of their geologic material realities, industrial scale extraction, and the myths, folklore and traditions that have shaped the contours of their individual cultures.

‘Over the course of six years, Dewe Matthews travelled across Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstsan, Russia and Turkmenistan, photographing the diversity of the region’s cultures, their unique connection to the land, and these countries’ ever-increasing economic reliance on global petropolitics, something that threatens to destroy and already fragile ecological landscape.

‘From dramatic images of the eternally burning gas crater known as the Door to Hell in the Karakum Desert in Turkmenistan to elaborate mausoleums built to service a generation newly rich on oil, Dewe Matthews’s striking series reminds the viewer of the ecological, corporeal and cultural cost of energy politics.’

Of this specific image:

‘A young woman bathes in crude oil at the sanatorium town of Naftalan. This ‘miracle oi’ is found exclusively in the semi-desert region of central Azerbaijan, and it is claimed that bathing in it for ten minutes a day has medicinal benefits.’

From the series Caspian: The Elements by Chloe Dewe Matthews (2010) Courtesy of the artist

Multiple clitoris by Carolina Caycedo (2016)

‘Part of her multidisciplinary project Be Dammed, which critiques the “mechanics of flow and control of dams and rivers” to address “the privatisation of waterways and the social and environmental impact of extractive, large-scale infrastructural projects”, Carolina Caycedo’s Water Portraits (2015 –) float across gallery spaces, suspended from ceilings and cascading along walls.

‘Printed on silk, cotton or canvas, Caycedo’s photographs of rivers and waterfalls are remixed into pulsating, fractal, perception-shifting images that invite the viewer to reflect on the fluidity of bodies of water, which resist the phallogocentric logic of extraction.

‘Ultimately, Caycedo’s work encourages us to view these bodies of water as life-sustaining, life-embracing, other-than-human living organisms and not just as resources for human extraction. A portrait of the water that powerfully carves through the long, narrow chasm known as Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat) – a canyon in the Iguazú Falls, on the border between Argentina and Brazil – Caycedo’s vibrantly coloured Multiple Clitoris evokes the feminist, orgasmic energy of our “corporeally connected aqueous community”.’

Installation view of ‘Multiple clitoris’ by Carolina Caycedo (2016) (Photo by the author)

Theme 2. Mutation: Protest and Survive

‘Women have a long history of protesting ecological destruction – from creative acts of civil disobedience and non-violent protest to armed resistance and climate legislation. Pamela Singh’s photographs of the Chipko movement document women resisting the felling of trees in northern India, while Format Photographers and JEB (Joan E. Biren) captured the women-led anti-nuclear peace movements of the 1980s in the UK and US, respectively.

‘Susan Schuppli’s film reflects on the right of ice to remain cold, as advocated by the Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier. Offering insights into the connections between patriarchal domination and the violence perpetrated against women and nature, the works in this section highlight the intertwined relationship between the survival of women and the struggle to preserve nature and life on earth.

‘Critical of the term “revolution”, in 1974 the French ecofeminist Françoise D’Eaubonne proposed the term “mutation”, which, she argued, would enact a “great reversal” of man-centred power. This grand reversal of power does not imply a simple transfer of power from men to women, instead it suggests the radical “destruction of power” by women – the only group capable of executing a successful systemic change, one that could liberate women as well as the planet.

‘Artists such as LaToya Ruby Frazier, Format Photographers, JEB, Pamela Singh and Poulomi Basu explore how communities of women – from web weavers to tree huggers and water defenders – have joined forces to combat violence against their bodies and land.’

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp: Embrace the Base action 12/12/1982 by Maggie Murray

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp: Embrace the Base action 12/12/1982 by Maggie Murray (1982) © Maggie Murray / Format Photographers Archive at Bishopsgate Institute Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas #74 by Pamela Singh

‘Pamela Singh’s powerful black-and-white documentary photographs of the Chipko movement depict women from the villages of the Garhwal Hills in Himalayas in Uttarakhand, northern India, calmly and peacefully clinging onto and embracing trees to save them from state- and industry-sanctioned loggers. Positioning themselves as human shields, with their arms interlocked around tree trunks, the women of this successful nonviolent protest became emblematic of an international ecofeminist movement eager to showcase the subordination of women and nature by global multinationals while underscoring women’s environmental consciousness.

‘The women were directly impacted by the rampant deforestation, which led to a lack of firewood as well as water for drinking and irrigation; by successfully opposing the planned fate of the trees, the women gained control of the means of production and the resources necessary for their daily lives, demonstrating the entangled relationship between the material needs of the women and the necessity to protect nature from domination and oppression.’

Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas #74 by Pamela Singh (1994) © Pamela Singh Courtesy of sepiaEYE

Cold Rights by Susan Schuppli (2020)

Theme 3. Earth Maintenance

‘The practice of earth maintenance and the labour of ecological care stand in direct opposition to the masculinist value system of the capitalist economy. In the late 1970s and early 80s, feminist artists such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Helène Aylon practiced earth care as a form of resistance, linking classed, racialised and gendered struggles to ecological justice.

‘Further, the works assembled here make clear the link between maintenance work in the domestic sphere, which was traditionally defined as “women’s work”, and the undervalued labour required to care for the planet.

‘From 1979 to 1980, Mierle Laderman Ukeles set out to make visible the overlooked yet fundamental work of New York’s sanitation workers, the caretakers of the city who repeatedly cleaned up the refuse and waste polluting its environment. Around the same time, Helène Aylon politicised earth care by gathering toxic soil from nuclear military sites, placing it inside pillowcases and carrying the soil to institutions of power in her “Earth Ambulance”.

‘Seeking new modes of earth maintenance and protest against the continuous exploitation of nature, through the mid-1990s Fern Shaffer performed private rituals at locations in need of healing. melanie bonajo’s film Nocturnal Gardening (2016), part of their series Night Soil Trilogy (2014 to 2016), positions women as agents of political and social change by studying how communities come together to forge alternative ways of living in harmony with the land. The audio installation The Grindmill Songs Project, from the People’s Archive of Rural India, brings into the gallery the collective singing of women from central India who are typically silenced while their daily existence is absorbed into a local and global system of value creation from which they do not benefit.’

A Draught of the Blue by Minerva Cuevas (2013)

Nine Year Ritual of Healing: April 9 1998 by Fern Shaffer

‘Over the course of nine years at locations across North America, Fern Shaffer performed private healing rituals at sites affected by the industrial-agricultural complex and impending extinction. Shaffer performed these self-designed spiritual performances at places including Big Sur, on California’s Pacific Coast; a cornfield outside Mineral Point in Wisconsin; on the summit of the Blue Ridge Mountain in Virginia; and at the Cache River basin in Illinois, among others. Photographed by her collaborator Othello Anderson in sequential images, Shaffer is pictured twisting and twirling in a handmade garment that conceals her bodily form and face, rejecting a human-centred and individualistic relationship to nature.’

Nine Year Ritual of Healing: April 9 1998 by Fern Shaffer (1998) Photo by Othello Anderson Courtesy of the artist

Theme 4. Performing Ground

‘For women artists in the 1970s and 80s, to locate the body as part of the natural world was to perform a highly politically charged act. At a time when even the countercultural “return” to nature was bound up in the discourse of patriarchy, picturing and performing the body as ecologically entangled carried with it radical feminist potential. Entwined, cocooned, or concealed, artists such as Laura Aguilar, Tee A. Corinne, Ana Mendieta, Fina Miralles, and Francesca Woodman blurred the boundaries between body and ground, undoing the distinction between human and more-than-human in their merging of animal, vegetal, and mineral. By deploying camouflage strategies, the artists gathered here resist demands for gendered and racialised bodies to be contained by settler–colonial politics or extractive logics, and rather forge mutual relationships with their environments.

‘To “perform ground” is to deliberately and strategically locate the self not merely in the world, but of it. It asks us to rethink established hierarchies of relations between the human and the more-than-human. In contrast with much Land art, which has staged large-scale and controlled interventions into the natural environment predominantly by men, the ecologically oriented works presented here by women artists place the body in communion with the land.

‘Judy Chicago, The Neo Naturists, and Xaviera Simmons heighten the visibility of their bodies in relation to the more-than-human world by painting themselves in vivid colours and patterns or using paint to critique racial stereotypes. In doing so, these artists explore how the representation of women and nature has always been an act entangled in history, power, and agency.’

Immolation from Women and Smoke, performed by Faith Wilding, photographed by Judy Chicago (1972)

‘In Immolation Chicago captures the performance artist Faith Wilding sitting cross-legged in the desert, enveloped in orange smoke. This work referenced the ongoing Vietnam War, the self-immolation of Buddhist monks, and similar acts by people in the United States, who were setting themselves alight to protest the war and advocate for peace, while the orange smoke alludes to Agent Orange, the herbicide that was sprayed to devastating effect in Vietnam.’

Immolation from Women and Smoke. Fireworks performance Performed by Faith Wilding in the California Desert by Judy Chicago (1972) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

The Body Covered with Straw by Fina Miralles (1975)

‘Fina Miralles’s conceptual photo-performance works from the 1970s embody a return to a profound relationship with nature. As she wrote in 1983 following a transformative five-month journey travelling through Argentina, Bolivia and Peru: “I am abandoning bourgeois culture and embracing Indigenous culture. The World Soul, Mother Earth and the protective and creative Pachamama.”

‘Read through this lens, Miralles’s series Relating the Body and Natural Elements, in which the artist cocoons herself in straw, as seen here, or surrenders her body to sand or grass until she disappears, her body merging with the land, illustrates Donna Haraway’s concept of “becoming with” and offers a metaphysics grounded in connection, challenging the illusion of separation – the erroneous belief that it is somehow possible to exempt ourselves from earth’s ecological community.’

Relationship: The Body’s Relationship with Natural Elements. The Body Covered with Straw by Fina Miralles (1975) Courtesy of MACBA

Nature Self-Portrait #5 by Laura Aguilar (1996)

‘For Laura Aguilar, photography was instrumental in visualising her identity, and in the mid-1990s she began creating powerful black-and-white nude self-portraits in nature. In contrast to the heteropatriarchal settler-colonial tradition of landscape photography, Aguila’s portraiture homes in on her identity as a large-bodied, working class, queer Chicana woman. Mirroring the natural forms of the rocky desert landscape of the American Southwest, in her Nature Self-portrait series, Aguilar inserts herself into a “racially stratified landscape” to become a boulder or perform as a tree.

‘As Macarena Gomez-Barris notes, Aguilar seems to want us to “trespass into the territory that feminists have long considered taboo by considering a profound relationship between the body and territory, one that provides a possibility for ecology of being in relation to the natural world. In that sense, her self-portraits provide a way to foreground modes of seeing that move away from capitalism, property and labour altogether, into a more unifying relationality that allows for haptic and sensuous relations with the natural world.”

‘Ultimately, by affiliating her body with the natural beauty of the landscape, Aguilar’s work both empowers and transcends the various categories of her identification.’

Of this specific photo:

‘In these works, Aguilar photographs herself resting beside large boulders that seem to echo her curvaceous bodily form. Facing away from the camera, and folding inward, her body emulates the cracks and dents of the boulders while the shadows cast from her body intensify the affinity with the stones before her. In a sense she has “grounded” herself in a landscape that oscillates with “the largeness of her own body”.’

Nature Self-Portrait #5 by Laura Aguilar (1996) © Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Isis in the Woods by Tee A. Corinne (1986)

The Isis series photoshop large close-ups of a human vulva into traditional landscape compositions creating surreal and disturbing juxtapositions.

Isis in the Woods by Tee Corinne (1986)

Theme 5. Reclaiming the Commons

‘Reclaiming the Commons considers the power dynamics of capitalist land ownership, environmental racism, and environmental memory, while reflecting on who has access to our common land, who owns the land and how earth-beings – both human and more-than-human – move through our increasingly enclosed natural world. Notions of ‘the commons’ are grounded in forms of egalitarian land stewardship in which members of a community have access to common land for pasturing animals, growing crops, and foraging, with feminists arguing that the commons are also social and economic sites that are crucial for female empowerment.

‘Questions of access to land are considered in Fay Godwin’s photographic series Our Forbidden Land (1990), which tracks how the long history of enclosures in Britain has shaped a sinister landscape in which fields and pathways are emptied of people through physical barriers, legal measures, and acts of dispossession. Diana Thater’s work RARE (2008) investigates the effects of enclosures from an interspecies perspective, focusing on the disappearing habitats of endangered species in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. In Al río/To the River (2016 to 2022), Zoe Leonard uses photography to testify to the weaponisation of landscapes through the transformation of waterways such as the Río Bravo/Rio Grande from a source of life and means of migration to a militarised border.

‘Environmental racism and memory are explored in the work of Ingrid Pollard, Dionne Lee, Mónica de Miranda, and Xaviera Simmons, who variously interrogate the racialised histories of settler–colonial and plantation landscapes. Their photographs – which are often manipulated with embroidery, collage, hand-tinting, and more – call into question the heteropatriarchal tradition of landscape photography and draw attention to the entwined struggles of decolonisation and the healing of our planet.’

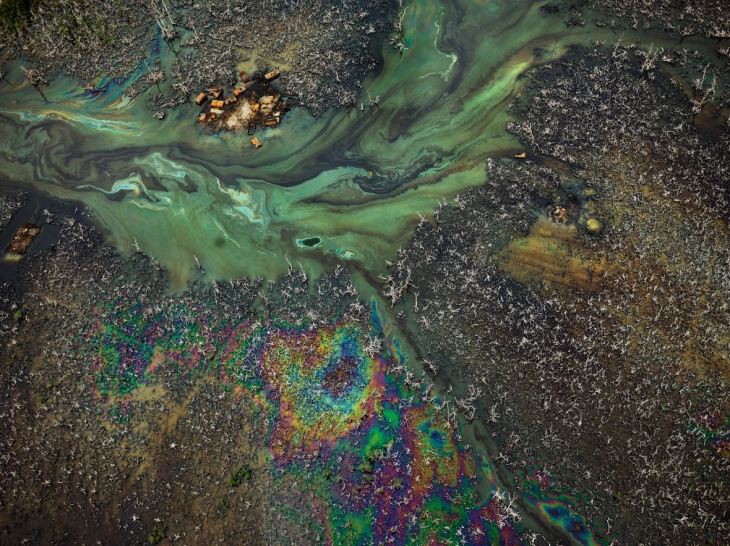

Karikpo Pipeline by Zina Saro-Wiwa

Theme 6. Liquid Bodies

‘Liquid Bodies explores the relationships between the human cultures of gender and sexuality and the world of water. The works assembled here imagine a relationship between human animals and the non-human world that rejects the dualisms of ‘natural and unnatural’, ‘alive and not alive’, or ‘human and non-human’ – colonial ways of seeing that divide the world into humans and everything else. Rather, the artists in this section start from a simple point of departure: we, too, are water. They look to the potential of this natural resource to destabilise a binary sense of gender and the categorisation of the world into neat taxonomies that shape conventional Western ideas of the human experience.

‘Ideas of watery immersion, submersion, and transformation unite the work of Nadia Huggins, Anne Duk Hee Jordan, Josèfa Ntjam, Ada M. Patterson, and Uýra. Cross-species becoming is explored in the Indigenous queer artist Uýra’s arresting photo-performances, in which the artist fuses with Amazonian plants, creating what she describes as hybrids of human, animal, and plant. Nadia Huggins’ striking self-portraits depict her becoming one with the corals that hug the coast of her Caribbean home. Playing out in the vast continuum of oceanic space, Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s film Ziggy and the Starfish (2018) depicts marine life as powerfully sensual. Bobbing along to a soundtrack culled from vintage erotic films and underwater sounds, it considers the porous boundaries of multispecies kinship that is presented as endlessly subversive. Colonial, mythic, and queer histories of water are further addressed in Josèfa Ntjam’s installation that considers Black being in the afterlives of Atlantic slaver.’

Ziggy and the Starfish by Anne Duk Hee Jordan (2018)

‘Taking its name from Ziggy Stardust, the androgynous, extraterrestrial rock star persona that musician David Bowie personified in the early 1970s , Anne Duk Hee Jordan’s sculptural video environment that houses the film Ziggy and the Starfish (2018) celebrates the fluidity of marine sexuality. The film pictures the sexual exploits of various ocean creatures with an exuberance and playful excitement, recalling the earlier work of the French photographer and filmmaker of marine life, Jean Painlevé. The effects of human-made climate change on the hydrosphere have become a key factor impacting the reproductive lives of marine animals, and by focusing on this aspect of the ecosphere Jordan underscores our deep entwinement with our fellow earthly inhabitants. In response to the present ecological crisis, the work offers a portal into the vivid world of our nonhuman cohabitors and looks to their colourful erotic lives as an example of how not only to think against binary dualisms, but to desire the seductively plural.’

Looking for ‘Looking for Langston’ by Ada M. Patterson (2021)

‘Looking for “Looking for Langston” by Ada M. Patterson is both inspired by and directly references Isaac Julien’s eponymous 1989 film, which offers a meditation on the life of the queer poet Langston Hughes and the wider cultural scene of the Harlem Renaissance in 1920s New York. As the title of the work suggests, Patterson, whose quest to learn more about the film ended in failure, constructs her own response that borrows from Hughes’s poetic imaginary as well as fragments she’s gleaned about Julien’s film. The result is a surreal and phantasmagoric exploration of Blackness and desire, using symbols such as the sailor and the sea to explore the fluidity of queerness. Patterson’s film also incorporates allusions to the histories of colonialism extant not only in Barbados (the artist’s birthplace and where this film was mostly shot) but also in Hughes’s United States and Julien’s United Kingdom. The film pays homage to these forebears, connected through oceanic bodies, legacies of Blackness and queerness, and the forever speculative pursuit of desire.’

Looking for ‘Looking for Langston’ by Ada M. Patterson (2021) Courtesy of Maria Korolevskaya and Copperfield

Mud by Uýra (2018)

‘Uýra is an indigenous artist, biologist and educator from Brazil who works in and around the riverine communities of the Amazon region. In these photo-performances, Uýra transforms into multi-species characters, fluidly merging the human and non-human by adorning herself with organic matter. Borrowing from the aesthetic language of drag, and its ability to disrupt the stasis of gender-normativity, Uýra exuberantly shows how other binaries, such as the one between human and nature, can also be understood to be fluid states that are performatively constructed. As an educator, Uýra also uses her works as pedagogical tools to uncover different forms of knowledge about the land that have been suppressed by the logic of Western extractive capitalism. In doing so, the works call for a material and spiritual restoration of the ravaged ecologies to which we belong.’

Lama (Mud) by Uýra (2018) Courtesy of the artist

Part 4. Participating artists

The curators claim that ‘at its core, the exhibition seeks to platform the work of artists from the Global South and Indigenous communities’, but does it? Here’s a full list of the contributors in alphabetical order:

- Laura Aguilar (US)

- Hélène Aylon (US)

- Poulomi Basu (India)

- Mabe Bethônico (Brazil)

- JEB (Joan E Biren) (US)

- melanie bonajo (The Netherlands)

- Carolina Caycedo (Columbia)

- Judy Chicago (US)

- Tee Corinne (US)

- Minerva Cuevas (Mexico)

- Agnes Denes (US)

- FLAR (Feminist Land Art Retreat) (US)

- Format Photography (UK)

- LaToya Ruby Frazier (US)

- Gauri Gill (India)

- Simryn Gill (Malaysia)

- Fay Godwin (UK)

- Laura Grisi (Italy)

- Barbara Hammer (US)

- Taloi Havini (Bougainville / Australia)

- Nadia Huggins (St Vincent & the Grenadines)

- Anne Duk Hee Jordan (Korea/Germany)

- Barbara Kruger (US)

- Dionne Lee (US)

- Zoe Leonard (US)

- Chloe Dewe Mathews (UK)

- Mary Mattingly (US)

- Ana Mendieta (Cuba)

- Fina Miralles (Spain)

- Mónica de Miranda (Angola/Portugal)

- Neo Naturists (Christine Binnie / Jennifer Binnie / Wilma Johnson) (UK)

- Otobong Nkanga (Nigeria)

- Josèfa Ntjam (France)

- Ada M. Patterson (Jamaica)

- PARI (People’s Archive of Rural India) (India)

- Ingrid Pollard (UK)

- Zina Saro-Wiwa (Nigeria)

- Susan Schuppli (Canada)

- Seneca Women’s Encampment for the Future of Peace and Justice (US)

- Fern Shaffer (US)

- Xaviera Simmons (US)

- Pamela Singh (India)

- Gurminder Sikand (India)

- Uýra (Brazil)

- Diana Thater (US)

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles (US)

- Andrea Kim Valdez (UK)

- Francesca Woodman (US)

- Sim Chi Yin (Singapore)

As you can see, in this list of 49 artists, 19 (39%) are from the USA, heartland of rapacious global capitalism. 5% of the global population; 40% of global art. And it’s always a pleasure to have Americans lecturing the rest of us about the environment. Compare with the American activists lecturing the visitor at the Hayward Gallery’s recent ‘Dear Earth’ exhibition. The full score is:

- US – 19

- UK – 6

- India – 5

- Brazil – 2

- Nigeria – 2

- Angola/Portugal – 1

- Bougainville / Australia – 1

- Canada – 1

- Columbia – 1

- Cuba – 1

- France – 1

- Italy – 1

- Korea/Germany – 1

- Malaysia – 1

- Mexico – 1

- The Netherlands – 1

- Singapore – 1

- Spain – 1

- St Vincent & the Grenadines – 1

US and UK participants number 25 or just over half the total. If you add in another 5 or 6 from Canada, Australia and Europe that makes roughly 30 out of 49. Whether having 60% of the contributors come from Europe and America equals platforming ‘the work of artists from the Global South and Indigenous communities’ is open to question.

Part 5. Other environmental art reviews

Artists have been worrying about the environment for decades but it’s only recently that exhibitions on the subject have broken through into the mainstream i.e. the big London galleries. RE/SISTERS is just the latest of a clutch of high profile eco-art exhibitions in London:

There is, as you might expect, some overlap: the work of Agnes Denes appears in both Dear Earth and RE/SISTERS, specifically her Agnes Denes’s ‘iconic’ 1982 work ‘Wheatfield: A Confrontation’, where she planted 8,000 square meters of wheat at Battery Park Landfill within sight of the Twin Towers in New York. I reviewed Mónica de Miranda’s recent exhibition at Autograph ABP. Here she’s represented by a piece I liked, Salt Island, five photographs into which have been sewn fine green threads hanging from the surface like the lianas of a tropical forest. They feel genuinely ‘chill’ as my son would say.

Installation view of ‘Salt Island’ by Mónica de Miranda. What you can’t see is the gossamer-fine green silk threads dangling from the foliage

What makes this exhibition sharply and distinctively different from the Hayward and Royal Academy shows is the fierce and unforgiving feminism which colours every aspect of it and every word of every caption.

Part 6. My responses

It’s a huge exhibition. The more you study it, the bigger and wider, the more confrontational or thought-provoking the issues become.

As to the actual subjects and images, a lot of these are very familiar: the ravages of open-cast mining, the oil spills which destroy rivers and lakes, the destruction of the rainforests, I feel like I’ve been reading about these all my life. How me and my friends thrilled to the film ‘Koyaanisqatsi’ with its vision of a world being heedlessly destroyed, and that was back in 1982!

In fact there are two ways of processing a huge, text-heavy like this. Or maybe three. 1) One is to read the captions and focus on the environmental and pollution aspect. On this perspective, although I felt I knew about a lot of the topics already – knew about the destructive effects of oil and mining, that we’re killing the oceans, I knew young women who actually took part in the Greenham Common protests, and so on. On the other hand, I’d never heard about the very bad effects of sand extraction documented by Sim Chi Yin, and about many of the other resistance movements in the developing world, such as the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army in India.

2) Second way is to react to the hyper-feminism of the captions, nod approvingly, rise to the bait, or be immediately struck by the illogic or contradictions of various parts of it. Rather than comment, I’ve quoted the wall captions at such great length so you can make up your own mind.

3) Third way is like my friend Andrew the gay designer. He prides himself on rarely if ever reading the wall captions at any exhibition, and instead reacting purely to the works themselves, liking them, disliking them (or making a note to pinch good ideas). Andrew avoids the captions because they almost always create a barrier between visitors and works. More and more often these days, as in this exhibition, they dispense a polemical discourse designed to coerce you into responding to all the works in an officially approved and constraining way. He hates that.

In contrast, I read every single caption, was appalled by a whole series of terrible environmental degradations they described, was irritated by the sanctimonious and misandric tone of most of them, and generally let my head be filled up with caption clutter which stopped me seeing what was actually in front of me. I need to be more like Andrew: stop reading the captions – just respond to the work.

Feminist discourse

Feel free to skip this bit. I’m not even 100% sure I completely believe what I’m writing. I’m just trying to work through my responses to the very strong feminist point of view shouting from every caption on every wall of this show:

In my review of Women, Art and Society by Whitney Chadwick (2012) I develop a sustained critique of this feminist theory way of thinking and writing. In brief, it feels like feminism has personally empowered hundreds and hundreds of millions and girls and women to feel more empowered and confident in their lives, which is an unqualified good thing. But that at the same time, on a purely political level, a weird dialectic is playing out in which feminist discourse – which has overrun and saturates all academic study of the humanities, art studies, media studies, film studies, feminist, gender and queer studies, history, literature etc etc, as it becomes more powerful, dense with theory and new terminology – has, at the same time and quite obviously, withdrawn from the real world. It has become the discourse of an academic elite, or of an intensely committed but very restricted membership.

Inside this group of university-educated middle-class women, of professors and lecturers of feminist studies, gender studies, queer studies and of generations of their students who have gone out into the world to make films, make art, make documentaries, write novels, become journalists and commentators – the zeal of the committed to their cause is matched only by the dazzling virtuosity of their jargon and the fierce extremity of their beliefs (which is why I’ve quoted the wall captions at such length, so you can see what I’m talking about).

Inside the cause, once you’ve accepted its basic premises (‘women’ are wonderful and have nothing to do with capitalism or environmental destruction; all men are toxic, are entirely responsible for the industrial revolution, for capitalism and raping the planet, are perpetrators of everyday sexism, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, mansplaining, manspreading, the manosphere etc etc) then everything makes sense and every event in the news, every word said by any man anywhere, every news story about some powerful man abusing his position, confirms this self-reinforcing worldview.

And the sustained bombardment of this exhibition’s captions work hard to cajole or coerce you into this looking glass world where all men are toxic capitalists and all women are heroic artists and activists.

It’s only when you step outside the bubble and shake your head, pinch yourself and awake from the dream, that you return to the real world, a world in which women in positions of supreme power are nothing like the portrait of ‘women’ created by the exhibition. Not long ago Liz Truss was Prime Minister of the UK and Priti Patel was Home Secretary. Today Suella Braverman is Home Secretary and the UK Environment Secretary is Thérèse Coffey. Both have acquiesced in Rishi Sunak’s rolling back of climate commitments. At least 5 million women voted for Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party, around 7 million women voted for Brexit. All this without going into women who voted for Donald Trump in the US. It’s a lovely statistic, though contested, that some 53% of white women voted for Trump in the 2016 Presidential election.

The precise figures don’t particularly matter. I’m just making the obvious point about the drastic disconnect between the rhetoric of this exhibition, and of so much feminist rhetoric, which:

- claims to speak for all women, which uses the word ‘women’ as if all women agree with radical feminism, when they quite obviously do not

- and claims that radical feminists are making ‘radical’ changes to the world, reshaping the world, overthrowing the cis-heteropatriarchy and so on when, in the real actual world that we live in, the exact opposite is happening; the forces of anti-feminism seem to be triumphing everywhere

Denying responsibility

Deep down, I think feminist exhibitions like this and the rhetoric which accompanies them (not the actual artists and certainly not the often brave and resourceful activists whose efforts shine through the miasma of jargon) are really about trying to escape blame, trying to place yourself on the side of the saints and martyrs, identifying with the nobility and righteousness of the cause.

After all, if you can blame everything terrible in the world on masculinist capitalism, on toxic masculinity, on extractivism and phallogocentrism, on the patriarchy, and on the heteropatriarchy and on the cis-heteropatriarchy, then you can escape blaming yourself.

(As a digression, note the inflation in terminology. The term ‘patriarchy’ no longer gives members of the tribe the same psychological kick that it used to, so it’s been escalated to become the ‘heteropatriarchy’ (i.e. rule of straight men); but maybe that is no longer enough to get the same kick and buzz so the dose has been increased to cis-heteropatriarchy. I understand that the people who coined these terms would say they are needed to the capture new insights into non-binary and gender-fluid identities of the younger generation. Nonetheless, at the same time, my view is that the the clear rhetorical escalation epitomised by the expansion of the original boo word ‘patriarchy’, also function as a form of magic: this increasingly hyperbolic jargon comes more and more to resemble chants and incantations designed to bind together the faithful and ward off the outside world. In this context, of global ecocide, to resist acceptance of your own responsibility; they are spells to help you deny that you too are completely embedded within the extractive capitalist economy.)

The exhibition’s section about extractivism tells us that the US military is the largest user of precious metals such as cobalt which are mined by virtual slave labour with disastrous ecological consequences in places like the Congo. Fine. But nowhere does it mention the well-known fact that the same kinds of rare metals, also ravaged out of the earth by forced labour in the poorest places, are also used in domestic smart phones, laptops, Alexa boxes and all the other digital accoutrements of modern life.

If you have a smart phone in your hand – and everyone I saw going round this exhibition did have a smart phone in their hand – then you’re guilty, you’re part of the extractive economy. No amount of railing against the patriarchy, or the heteropatriarchy, or the cis-heteropatriarchy, gets you off the hook.

My personal view is that all of us in ‘the West’, men and women, are guilty and that we should start from this frank acknowledgement of our mutual responsibility. The streams of complex jargon-laden discourse reeling at the visitor from every direction are, in my opinion, designed to hide this one fundamental truth because they continually exonerate ‘women’ i.e. half the population, as in some way magically not responsible. If all women are artists and activists resisting the destruction, then it follows that no women can be to blame.

My position is that all of us, men as well as women, are in the same boat, facing the same peril, and must work together to try and find solutions. Privileging all women and denigrating all men i.e. sowing division and recrimination, feels like the last thing we need to be doing right now. We should be building bridges and finding allies and forming coalitions to try and force major change.

In my view, everyone in the western world needs to drastically alter their lives in order to reduce their carbon footprint and to keep their involvement in environmental destruction to an absolute minimum. That means not having a car, never flying again, having few if any digital gizmos, as well as going vegetarian, if possible dairy free and vegan, and try to reorganise your finances to support environmentally friendly banks, insurance and pension companies. The same prospectus outlined by Christiana Figueres 5 or 6 years ago. On a political front, lobby your council or MP to take green and environmentally friendly policies wherever possible. Vote for the parties most likely to carry out green policies, which in the UK, at the next election, means Labour, since any Green vote risks splitting the anti-Conservative vote, as at the recent Uxbridge by-election.

The mindset of an exhibition like this which tells all its female visitors that all the bad stuff can be blamed on men, and that simply being a woman automatically qualifies you for membership of the sisterhood of artists and activists, allows you to deny your guilt and your complicity in the extractivist systems this exhibition so vividly depicts.

Revolutionary rhetoric without the revolution

To take another angle, so much of this kind of rhetoric, the ‘radical’ rhetoric shouting from every picture caption, is just right-on revolutionary posing without the slightest intention of doing anything ‘revolutionary’.

In this respect hardly anything has changed since Tom Wolfe’s 1970 essay ‘Radical chic’ satirised the haute bourgeoisie gathered for an evening at Leonard Bernstein’s New York apartment to lionise members of the revolutionary Black Panther Party, who were simply too too adorable for words! So radical, darling.

Something similar can be felt here in texts which flirt with the rhetoric of revolution without the slightest intention of upsetting the cosy worlds of the Barbican Friends and Corporate Sponsors who have gathered to cheer this marvellous exhibition and applaud the curators for their wonderful work.

This thought occurred at the moments when the texts occasionally reverted to pure, old school Marxist rhetoric, revealing the ancient communist assumptions which underpin them. Thus the catalogue, when describing the achievement of the tree huggers of Chipko, praises them for regaining ‘control of the means of production’.

This is of course a straight quote from The Communist Manifesto and the millions of communist books, pamphlets, lectures which repeated it all around the world for the subsequent 140 years (1848 to 1988) with, in the end, zero effect. How many countries in the world currently implement the Marxist-Leninist social and economic policies of which this used to be a central plank? None.

The exhibit which most repeatedly invokes the word ‘revolutionary’ is the series of Poulomi Basu’s photographs which capture (very vividly) members of the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army who are actually fighting, with actual guns, against the activities of mining companies in south central India and the Indian security forces. They describe themselves as a revolutionary force. A panel in the catalogue is devoted to ‘Comrade Matta Rattakka’ who died a ‘martyr’ to the cause. This is the rhetoric of the old Soviet Union and its satellites and Cold War guerrilla movements. These are phrases I haven’t read, delivered straight, with no irony, for decades.

Untitled from the series Centralia (2010 to 2020) by Poulomi Basu

On one level Basu’s work is gripping photojournalism of a real conflict. But its inclusion in this exhibition incorporates it into what is, in practice, revolutionary chic without the slightest possibility of a revolution. Because revolutions are difficult, violent and, even if they initially triumph, we now know, over the long term, degrade and collapse.

What the godly revolution in Britain in the 1640s and the French revolution in the 1790s and the Russian revolution in the 1910s and the Iranian revolution in the 1970s all demonstrated is that it’s relatively easy to overthrow a tyrannical regime and seize power. But it is then fiendishly difficult, if not impossible, to impose your revolutionary values on the vast majority of the population who don’t share them and never will share them. On the whole, revolutions can only it can only be carried forward with large scale repression of and execution of the classes which oppose you, more often than not, the bien-pensant liberal bourgeoisie. The liberals tend to be first up against the wall in any revolution. I.e. exactly the kind of people who attend exhibitions about revolutions.

The beautiful thing, for its exponents and their followers, about this kind of feminist rhetoric about ‘revolutions’ and overthrowing masculinism and abolishing the patriarchy and rebelling against the military-industrial complex, the summaries of Françoise D’Eaubonne’s theory of a ‘great reversal’ of man-centred power, and countless thousands of variations on the theme – the great thing about it is that they will never happen.

Feminists get to thrill in the writing or reading of extensive urgent texts bravely declaring radical change and revolutionary overthrow and interrogating gender stereotypes and all the rest of it, all the time confident in the knowledge that any actual revolution, any genuinely transformative overthrow of the existing structures of power, won’t actually ever happen.

It’s bourgeois play acting. It’s bourgeois posing with the rhetoric of ‘revolution’ with absolutely no intention of ever carrying it out. Because if anything like it ever was carried out, the revolutionary feminists would make the same discovery as the Puritans in the 1640s, the Jacobins in the 1790s, the Bolsheviks in the 1920s and the Party of God in the 1980s, that the majority of the population they would find themselves governing don’t share your values and don’t want your revolution.

That’s what I mean by saying that this kind of bourgeois feminism exists in an academic dreamland, will never be tested against reality, and so its followers will be able to live their entire lives without ever having to experience the disillusions of real power, instead enjoying a pleasing sense of righteousness to the end of their days.

Non humans

The exhibition does have interesting things to say about non-humans. All of these struck me as being more interesting and more true than just blaming men for everything. Quite obviously humans of all sexes are the problem. The world would be better off without us and, at moments in the show, this basic truth peeped through, struggling against the curators’ aim of redeeming and absolving women. But no humans are free of guilt. Eurowestern liberals like the curators like to fetishise the lifestyles of Indigenous peoples, whether in the Amazon or Australia, but they kill animals, they burn the bush, they poo in the rivers, there are just a lot, lot fewer of them. Given modern medicine to help them survive, they also breed quickly, overfill their ecosystems, start degrading everything. By trying to exculpate and valorise women the exhibition seeks to hide the bleaker truth: If you want to overthrow something, you shouldn’t be bothering with the cis-heteropatriarchy, you should be trying to overthrow the tyranny of Homo sapiens over all the organisms of the world.

Saving the environment?

Lastly, do exhibitions like this do anything at all for ‘the environment’? No. Like all art exhibitions, they preach to the converted, to the white liberal bourgeois bien-pensant converted who I saw strolling round snapping everything with their latest model camera-phones, white, middle-aged, university-educated women who are already signed up to ‘the revolution’, chat confidently about the complete transformation of masculinist society, discuss how ghastly cis-heteropatriarchal capitalism is, before rushing off to their next viewing, clutching their phones and their designer bags, before catching the plane back to New York.

At the press launch I heard the American accents of some of the American artists and journalists who’d flown over to cover it. Maybe when they drive their big American cars or take their plane trips to Australia or Amazonia, planet earth realises that they’re feminist flyers and drivers and so their carbon dioxide, magically, doesn’t count. In my opinion we have to stop, we all have to stop, men, women and every other gender. The era of cheap foreign holidays and long road trips, of commuting by car and taking weekend city breaks to the continent, the era of new gizmos every Christmas, buying new clothes to be in the fashion, of steaks and burgers and unlimited meat, of vast hecatombs of slaughtered pigs and cattle and chickens taking up huge resources, pumped full of antibiotics, their chemical waste poisoning drinking water, the era of boundless mindless consumption is drawing to a close, even if most people haven’t realised it yet.

Well, I’ve given you enough visual and textual evidence. What do you think?

Related links

Related reviews

Women’s art book reviews