And what marvellous exciting fun it was!

(Lucky Break)

This 1977 collection of Roald Dahl short stories is, as one of his schoolboys might say, a bit of a swizz because, out of the seven texts in this collection only four of are actually short stories – the last two are autobiographical sketches about the war and ‘The Mildenhall Treasure’ is a factual article from way back in 1946, all three of which had been previously published elsewhere.

- The Boy Who Talked With Animals (story)

- The Hitch-Hiker (story)

- The Mildenhall Treasure (article)

- The Swan (story)

- The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (story)

- Lucky Break (memoir)

- A Piece of Cake (memoir)

They’re all children’s stories, even the war memoirs – not for small children, exactly; probably for younger teens. It’s indicative that the edition I read was published by Puffin, Penguin’s imprint for children. One of aspects of the children-y approach is the gleeful hyperbole found throughout the pieces:

- As a matter of fact, he told himself he was now almost certainly able to make money faster than any other man in the entire world. (page 144)

- ‘You will be the richest man on earth.’ (p.156)

Another minor verbal tic which indicates their target audience is the liberal use of Dahl’s favourite words, ‘marvellous’ and ‘fantastic’, both of which, of course, appear in the titles of two of his most popular children’s books.

And now, very quickly, there began to come to him the great and marvellous idea that was to change everything. (Henry Sugar, page 153)

The Boy Who Talked with Animals (23 pages)

A strange and eerie story told by a narrator who’s gone on holiday to Jamaica. The taxi driver taking him to the hotel spooks him with stories of weird voodoo stuff which still goes on in the mountains. Then when he arrives at the hotel it’s perfectly pleasant and yet it gives him a bad vibe. And then the maid tells him all about a guest, a Mr Wasserman who was taking a photo of the sunset from the beach when a huge coconut fell on his head and knocked him dead. Although all this is quite serious it has a comic-book simplicity about it.

Anyway, the main action kicks off when the narrator, idling sitting on his balcony one day, hears a great hubbub from a crown of guests assembling on the beach.

This is a first-person fiction piece of medium-length writing. The narrator, on advice from friends, decides to vacation in Jamaica. One night, a sea turtle, ancient and huge, is caught by a group of fishermen. Rich people want to buy it, while the manager of a nearby hotel wants to make turtle soup out of it, but both plans are foiled when a little boy appears and shames the crowd for their cruelty. His parents explain that he has a deep affinity for animals, and even talks to them. The boy’s father pays off the fisherfolk and hotel manager, and the turtle is set free. The next day, the boy is missing, and the fisherfolk reveal that they have seen the child riding on the back of the sea turtle into the distance.

A turtle has landed on a resort beach in Jamaica and everyone wants to kill it for the meat and its shell. A small boy David becomes hysterical and tries to save the turtle. His parents explain that he is very sensitive to animals and they volunteer to buy the turtle from the resort owner. While they are haggling over the price, David talks to the turtle and tells it to swim away. During the night the boy himself disappears and next day two local fishermen come back with a crazy story – they have seen David riding the turtle out in the middle of the ocean!

The Hitch-Hiker (15 pages)

That rare thing, a Roald Dahl story with a happy ending, no revenge or poisoning or murder in sight.

The narrator is driving up to London in his brand new BMW 3.3 Li when he spots a hitchhiker. As the man gets in the narrator observes his rat-like features and long white hands, his drab grey coat which makes him look even more rattish. They talk about the model of car the narrator’s driving and when the narrator boasts that its top speed is 129 mph, the hitch-hiker encourages him to put the manufacturer’s claims to the test. So the narrator puts his foot down, 80, 90, 100, 105, 110, 115 miles an hour. Just as they get into the 120s they both hear a police siren go off and realise a police motor cycle is after them.

The traffic cop is strict, unbending and sarcastic. He takes his time and is rude and officious to both of them before writing out a ticket and hinting that breaking the limit by such a whopping margin will definitely result in a big fine and maybe even a prison sentence. With that threat he motors off leaving the narrator to resume his journey at a sensible law abiding speed.

The narrator frets over the doom awaiting him and so the hitchhiker sets about cheering him up. He challenges the narrator to guess his true profession. As a clue he starts to reveal various items from the narrator’s person starting off, improbably enough, with his belt, before going on to reveal the narrator’s wallet, watch and even shoelace.

Gobsmacked, the narrator calls the hitchhiker a pickpocket but the latter is a bit miffed and insists on being called a ‘fingersmith’ – just as a goldsmith has mastered gold, so he has mastered the adept use of his long and silky fingers, which he refers to as his ‘fantastic fingers’.

After his initial amazement at his friend’s abilities the narrator relapses back into gloom at the prospect of being charged, fined and maybe even imprisoned for his moment of madness. At which point, in a dazzling conclusion to the story, the hitchhiker reveals that he has stolen both of the police officer’s notebooks, which contain the cop’s copies of the tickets he gave them and the details of their offence.

Delighted, the narrator pulls over and he and the hitchhiker gleefully make a little bonfire of the policeman’s notebooks. A rare example of a Dahl story with a joyful ending.

The Mildenhall Treasure (1946: 27 pages)

Not a short story at all, but a factual article.

A modern preface explains that Dahl was unmarried and living with his mother when he read about the discovery of the Mildenhall treasure. He motored over to interview the hero of the story, Gordon Butcher, a humble ploughman, and this 27-page text is a kind of dramatisation of events.

Put simply, in January 1942 the owner of some farmland in Suffolk contracted one Sydney Ford to plough his fields for him and Ford sub-contracted the job to Gordon Butcher. Butcher was ploughing away when his plough struck something. When he investigated he found the edge of a big metal disc. Not sure what to do he went to see Ford who accompanied him back to the field and the pair dug out over thirty pieces of obviously man-made metal objects. As they did it snow began to fall and eventually the hole was covered in snow and Butcher’s extremities had gone numb with cold so he was happy enough when Ford told him to go home to his wife and a roaring fire and forgot all about it.

Meanwhile Ford took the treasure home in a sack and, over the following weeks and months, used domestic metal cleaner to clean off the tarnish and reveals the objects for what they were, the most impressive hoard of buried Roman treasure ever found in Britain.

Now all this took place during wartime, and from Ford’s house he could hear Allied bombers taking off to pound German cities and many of the norms and conventions of civilian life had been suspended. On the face of it, according to law, Butcher and Ford should have reported the find; it would have been claimed in its entirety by His Majesty’s government but Butcher, as the first finder, would have been eligible for the full market value of the trove, which Dahl gives as over half a million pounds.

But neither man reported it, in breach of English law. The digging in the increasingly heavy snowfall is the first significant or dramatic scene. The next one comes when Dahl describes the mounting excitement of Ford as he uses ordinary domestic cleaner to slowly work off the centuries of grime and reveal the sparkling silver underneath.

The third one comes when Ford has an unexpected visitor, Dr Hugh Alderson Fawcett, a keen and expert archaeologist who used, before the war, to visit Ford once a year to assess whatever finds Ford had made for, as the text explains, old arrowheads and minor historical debris often crop up in the fields of Suffolk which were, in the Dark Ages, the most inhabited part of Britain.

Anyway, by some oversight Ford kept most of the treasure under lock and key but had left out two beautiful silver spoons, which each had the name of a Roman child on them and so were probably Roman Christening spoons. The most dramatic moment in the story comes when Ford welcomes Fawcett into his living room but then realises the spoons are on the mantlepiece, in full sight. He tries to distract the doctor’s attention but eventually Fawcett sees them, asks what they are, and, upon examining them, almost has a heart attack as he realises their cultural importance and immense value.

Ford reluctantly confesses to when he found them and even more reluctantly admits there are more. When he unlocks his cupboard and shows the hoard to Fawcett the latter nearly expires with excitement.

In a way the most interesting moment comes when Dahl, showing the insight of a storyteller, admits that the most interesting part of the tale, all the dramatic bits, are over. Now it’s just the bureaucracy and administration. The hoard is reported to the police and packed off to the British Museum. In July 1946 a hearing is held under the jurisdiction of a coroner but it’s a jury which decides to award both Ford and Butcher £1,000, a lot of money but nowhere near the half million Butcher might have got if Ford had told him to report the find immediately.

You can read up-to-date information about the treasure on the Mildenhall Treasure Wikipedia page, including a reference to what Wikipedia calls Dahl’s ‘partly fictional account’.

The Swan (25 pages)

His lazy truck driver Dad buys thick, loutish Ernie, a .22 rifle for his 15th birthday. He and his mate Raymond go straight out on this fine May morning and start taking potshots at songbirds, stringing their bodies up from a stick Ernie carries over his shoulder. Then they come across school swot, weedy bespectacled 13-year-old Peter Watson.

At which point commences the main body of the story in which these two thugs really seriously bully Peter. First of all they march him to the nearby train line where they truss him hand and foot and then tie him to the sleepers. It is genuinely tense as Peter lies there trying to work out how low a train’s undercarriage is, and systematically moving his head and feet back and forth to try and dig deeper into the gravel. Dahl gives a tremendously vivid description of the express train suddenly appearing like a rocket, and roaring over Peter’s head till he feels like he’s been swallowed by a screaming giant.

But he survives, dazed and in shock. The bullies have watched from the nearby verge and now stroll down and untie Peter but keep his hands trussed. They push him ahead of them as they set off for the lake. Here they spot a duck and, despite Peter’s heartfelt please, shoot it. At which Ernie has the bright idea of treating Peter as their retriever, forcing him to wade into the water and bring back the corpse of the duck.

Next they spot a swan, a beautiful swan sitting regally atop a nest in the reeds. Peter begs them, tells them it’s illegal, tells them that swans are the most protected birds in the country, they’ll be arrested etc, but these guys are idiots as well as hooligans and Ernie raises his gun and shoots the swan dead. Then they threaten to kick and beat Peter unless he wades into the reeds and fetches the body.

It’s at this stage that things start to take a turn for the macabre or gruesome or possibly surreal. Peter loses all restraint and accuses Ernie of being a sadist and a brute at which point Ernie has another of his brainwaves and asks if Peter would like to see the swan come back to life, flying happily over the lake?

Peter asks what the devil he’s talking about, but then Ernie asks Ray for his pocket knife and sets about sawing off one of the swan’s wings. He then cuts six sections from the ball of string he always carries in his jacket and then…tells Peter to stretch out his arm. While Peter says he’s mental, Ernie proceeds to tie the swan’s wing tightly to Peter’s arm. Then he cuts off the other wing and ties it to Peter’s other arm. Now Peter has two swan’s arms attached to his arms.

So far so weird, but now the story moves towards a line or threshold, for Ernie now insists that Peter climbs a weeping willow growing by the lakeside, climbs right to the top and then ‘flies’. Peter seizes the opportunity of escaping from the bullies and makes the best of struggling up through a willow tree while encumbered with two whopping great swan wings, but eventually reaches the highest branch capable of bearing his weight, some 50 feet above the ground.

If he thought he could escape the bullies he was mistaken for they have stepped back to have clear sight of him, and Ernie proceeds to shout at him, telling him to fly. What madness, Peter thinks and doesn’t budge. At which point Ernie tells him he must fly or he will shoot. Peter doesn’t budge. Then Ernie says he’ll count to ten. He gets to ten and fires, deliberately shooting wide, in order to scare Peter who still doesn’t budge. Then, getting cross, Ernie shoots him in the thigh.

Now, at this pivotal moment, Dahl interjects a bit of editorialising. he tells us that there are two kinds of people, people who crumble and collapse under stress, pressure and danger or the smaller number of people who abruptly flourish and triumph. This, we take it, is experience garnered during his service in the war. But it also serves to paper over the crack, the red line, where the narrative crosses over from weird but plausible into wholly new realm of magical realism.

For, transformed by rage and frustration, Peter spreads his swan’s wings and…flies! The bullet in his leg knocked both his feet from under him but instead of plummeting to earth he sees a great white light shining over the lake, beckoning him on, and spreads the great swan wings and goes soaring up into the sky.

The narrative cuts to the eye witnesses in the village who see a boy with swan wings flying overhead and then cuts to Peter’s mother, doing the washing up in the kitchen sink when she sees something big and white and feathered land in her garden and rushes out to find her beloved little boy, to cut him free from the wings and start to tend the wound in his leg.

The transcendence of this, the tying on of wings and a boy’s transformation into a bird, remind me of the several J.G. Ballard short stories which depict men obsessed with flying like birds, in particular the powerful 1966 story Storm-bird, Storm-dreamer.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (71 pages)

By far the longest of Dahl’s short stories, this tale is more accurately described as a novella, whose length justifies the compilation and naming of the book around it. Having just finished it I can see that it could possibly have been a book in its own right, padded out with illustrations to book length. Instead the publishers padded it out to book length by adding a couple of other stories and some already-published war memoirs.

It’s an odd production, firstly in that it contains lengthy stories nested within each other, as you’ll see. We start with an extended introduction to the character of Henry Sugar who is painted as a thoroughly despicable person. He has inherited great wealth, is lazy and idle and spends most of his time, like many of his class, gambling on anything that moves.

Sugar goes to stay with a posh lord (Sir William Wyndham at his house near Guildford) and when his friends set up a game of canasta he draws the short straw and is the odd man out, so he wanders disconsolately into the library and mooches around till he finds an old exercise book in which is written the second story, the story-within-a-story.

For the exercise book turns out to be an account written by a British doctor in India in 1934. It is titled ‘A Report on an Interview with Imhrat Khan, The Man Who Could See Without Eyes, by Dr John Cartwright, Bombay, India, December 1934’.

This is a long, detailed account in its own right. This Cartwright is sitting with others in the Doctors Rest Room in Bombay Hospital when an Indian comes in. He calmly explains that he can see without using his eyes. After their initial mockery the doctors test him by putting a temporary sealant on his eyes, covering them with bread dough, then cotton wool, then bandaging them thoroughly. But, to their astonishment, the man heads out into the corridor, avoids other people, manages the stairs just fine, walks out the building, gets onto a bicycle and cycles out into the roaring traffic all without the use of his eyes.

It turns out that this fellow makes his living as part of a travelling circus where he’s one among many gifted performers such as a prodigious juggler, a snake charmer and a sword swallower. Dr Cartwright finds this out when he goes to see the circus that evening (at the Royal Palace Hall, Acacia Street). He then goes backstage to Khan’s dressing room and asks if he can interview him about his amazing powers. He will write up the account and try to get it published in something like the British Medical Journal. Khan agrees so Cartwright takes him to a restaurant and over curry Khan tells him his story.

So this is the third account, a story-within-a-story-within-a-story, which switches to a first-person narrative. Khan explains that he had a lifelong fascination with magic. When he was 13 a conjurer came to his school. He was so entranced that he followed him to Lahore where he became his assistant. but is disillusioned when he discovers it is all trickery and not real magic. He learns about the yogi, holy men who develop special skills. While looking for one he joins a travelling theatre company to make a living. Then he learns that the greatest yogi in India is Mr Banerjee, so he sets off to find him. He tracks him down to the jungle outside Rishikesh where he hides and witnesses the great man praying and levitating. When he steps forward to introduce himself Banerjee is furious at being spied on and chases Khan away. But the boy returns day after day and his persistence wears Banerjee down. Eventually he agrees to talk, says he never takes disciples, but recommends a colleague, Mr Hardwar.

Hardwar takes him on and thus begins a series of challenging physical and mental exercises, for three years. Eventually he needs to earn a living and rejoins a travelling show where he performs conjuring tricks. In Dacca he comes across a crowd watching a man walk on fiery coals and, when volunteers are requested, he goes forward and walks on burning coals himself.

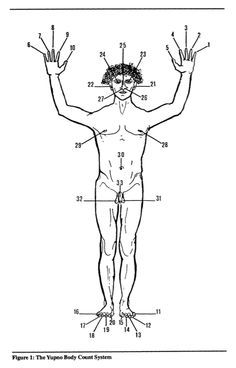

He has heard tell that the ultimate test of a yogi’s powers is to see without using your eyes and so sets his heart on achieving this skill. (p.123). Slowly he realises that our senses have two aspects, the outer obvious one, and the inner version of that sense. He cultivates his inner sense of sight and the narrative form allows Dahl to convince us that Khan slowly slowly acquires the ability to see objects with his eyes closed.

By 1933 when he is 28 he can read a book with his eyes closed. He explains to Cartwright that the seeing is now done by any part of his body and demonstrates it by placing himself behind a door except for his hand which he sticks round the door. Then he proceeds to read the first book Cartwright takes off the shelf with his hand. Cartwright is staggered.

It is now late and time for Khan to go to bed. Cartwright thanks him and drives him home, then goes back to his own place but can’t sleep. Surely this is one of the greatest discoveries ever made! If this skill can be taught then the blind could be made to see and the deaf to hear! Cartwright gets a clean notebook and writes down every detail of what Khan has told him.

Next morning Cartwright tells all to a fellow doctor and they agree to go to the performance that evening and afterwards take Khan away from the tacky world of travelling performers and set him up somewhere safe where scientists can study him.

But when they get to the Royal Palace Hall something is wrong, there is no crowd and someone has written ‘Performance cancelled’ across the poster. When Cartwright asks he is told that ‘The man who can see without eyes’ died peacefully in his sleep. At one point in his long narration, Khan had made a point of telling him that a good yogi is sworn to secrecy and is punished for divulging his secrets. Well, this is the handy narrative contrivance Dahl has used to eliminate his wonder-worker. He told his secrets, he died.

Cartwright is devastated, finishes writing up his account with this sad coda, signs it and…40 or so years later, this is the old exercise book which Henry Sugar has just randomly picked up and read in the library of Sir William Wyndham!

Sugar has read it alright but the only thing he took from it was one throwaway remark by Khan that he could read the value of playing cards from behind because he could see through playing cards. As an inveterate gambler Sugar is dazzled by the possibilities of this power. He steals the notebook and sets about copying the exercises detailed in it. Months pass and he thinks he’s beginning to acquire the ability to empty his mind and visualise.

At the end of one year of hard training to focus and visualise Sugar tests himself and discovers that he can see through the back of a playing card to see its value, although it takes about four minutes to do so. A month later he can do it in 90 seconds, six months later he’s got it down to 20 seconds. But thereafter it gets harder, and it takes another eight months before he gets it down to 10 seconds. By now he has developed phenomenal powers of concentration but getting his reading time down to his target of four seconds takes another whole year, making three years and three months in total.

Then commences the real core of the story. In a sense all the preliminary matter about the Indian yogi is so much guff; conceivably it could have been a scientific inventor coming up with the discovery or any other kind of pretext or excuse which gets the protagonist to this point, namely, Being able to see the value of concealed cards at a casino.

For on the evening of the day when he finally visualises a card in 4 seconds, Henry puts on a dinner jacket and catches a cab to one of the most exclusive casinos in London, Lord’s House. Here he discovers he can predict which number is going to come up at roulette, bets £100 and wins at odds of 36 to 1. (I was surprised at this because all the effort of the preceding narrative has been about seeing what’s there with his eyes shut whereas this, his first trick in a casino, is entirely about predicting the future, which is a completely different ability altogether.)

What makes these children’s stories, but very effective children’s stories, is their vivid exaggeration. Everyone and everything is always the best in the world:

[The cashier] had arithmetic in his fingers. But he had more than that. He had arithmetic, trigonometry and calculus and algebra and Euclidean geometry in every nerve of his body. He was a human calculating-machine with a hundred thousand electric wires in his brain. (p.145)

Also the simplicity of the thoughts, and of the layout which emphasises that simplicity. The following should be a paragraph but isn’t, it is laid out like this because it is catering to children:

And what of the future?

What was the next move going to be?

He could make a million in a month.

He could make more if he wanted to.

There was no limit to what he could make.

Anyway, the surprising thing is that Henry is not thrilled by his staggering winnings. A few years earlier such a win would have knocked his socks off and he would have gone somewhere and splashed the cash on champagne and partying. Not now. To his surprise Henry feels gloomy. He is realising the great truth, that ‘nothing is any fun if you can get as much of it as you want’ (p.148).

Bored and a bit depressed Henry stands at the window of his Mayfair flat and, out of boredom, lets one of the £20 notes of his winnings be taken away by the breeze. An old man picks it up. He lets another go and a young couple get it. A crowd begins to form under his window. Eventually Henry throws his entire winnings of thousands of pounds into the street which, predictably, causes a small riot and blocks the traffic.

A few minutes later a very angry policeman knocks on his apartment door and tells him not to be such a blithering idiot. Where did he get the money from etc and Henry gives details of the casino, but what strikes home is the copper says if you want to chuck money away, why not give it to somewhere useful like an orphanage.

This gives Henry a brainwave. After thinking it through a bit he decides he will devote his life to charity. he will move from city to city, fleecing the casinos for huge sums before moving on to the next. And he will use all the money he makes to set up orphanages in each country.

He’ll need someone to handle the money side so he goes to see his accountant, a cautious man named John Winston. Winston doesn’t believe him so Henry a) tells him the values of cards laid face down on his table b) wins a fortune in matchsticks from a little game of blackjack they have in his office c) takes him to a casino that evening (not the Lord’s House) where he wins £17,500.

Winston agrees to be his partner but points out that the kind of revenue he’s suggesting will all be taken by the taxman. He suggests they set up the business in Switzerland so Henry gives him the £17,500 to organise the move, set up a new office, move his wife and children out there.

A year later Henry has sent the company they’ve set up £8 million and John has used it to set up orphanages. Over the next seven years he wins £50 million. Eventually, as in all good stories, things go wrong and trigger the climax. Henry is foolish enough to win $100,000 at three Las Vegas casinos owned by the same mob. Next morning the bellhop arrives to tell him some dodgy men are waiting in the foyer. The bellhop explains that, for a price, he’ll let Henry use his uniform to get away. But he must tie the bellhop up to make it look kosher. This he does, tucks a grand under the carpet as payment, and makes his escape dressed as a bellhop.

He catches a plane to Los Angeles because the use of a disguise has given him an idea. He goes to see the best makeup artist in Hollywood, Max Engelman. He explains his special powers and asks if he wants to earn $100,000 a year. Max joins him and together they travel the casinos of the world appearing at each one in disguise. The story has now become a full-on children’s story, revelling in the sheer pleasure of dressing up in ever-more preposterous identities, using faked passports and id cards.

Eventually the story ends when Henry Sugar dies. The narrator tots up the figures. Henry died aged 63. He had visited 371 major casinos in 21 different countries or islands. During that period he made £144 million which was used to set up 21 well-run orphanages around the world, one in each country he visited.

In the last few pages Dahl gives a children’s style version of how he came to write the book, namely John Winston rang him up, invited him to come and meet him and Max, showed him Cartwright’s notebook, and commissioned him to write a full account. Which is what he’s just done. No matter how absurd and fantastical the story, it is treated with Dahl’s trademark clear, frank limpidity.

Lucky Break

This is a non-fictional account of how Dahl became a writer, condensing material from his two autobiographical books, ‘Boy and ‘Going Solo’. It highlights key events from his childhood, school days and early manhood up to the publication of his first story.

A Piece of Cake (1946)

From Wikipedia:

An autobiographical account of Dahl’s time as a fighter pilot in the Second World War. It describes how Dahl was injured and eventually forced to leave the Mediterranean arena. The original version of the story was written for C. S. Forester so that he could get the gist of Dahl’s story and rewrite it in his own words. Forester was so impressed by the story (Dahl at the time did not believe himself a capable writer) that he sent it without modification to his agent, who had it published (as ‘Shot Down Over Libya’) in The Saturday Evening Post, thereby initiating Dahl’s writing career. It appeared in Dahl’s first short story collection ‘Over to You’, published in 1946.

Credit

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More by Roald Dahl was published by Jonathan Cape in 1977. References are to the 2001 Puffin paperback edition.