Note: to avoid misunderstanding, I believe Freud is a figure of huge cultural and historical importance, and I sympathise with his project of trying to devise a completely secular psychology building on Darwinian premises. Many of his ideas about sexuality as a central motive force, about the role of the unconscious in every aspect of mental life, how repressing instinctual drives can lie behind certain types of mental illness, his development of the talking cure, these and numerous other ideas have become part of the culture and underlie the way many people live and think about themselves today. However, I strongly disapprove of Freud’s gender stereotyping of men and women, his systematic sexism, his occasional slurs against gays, lesbian or bisexuals and so on. Despite the revolutionary impact of his thought, Freud carried a lot of Victorian assumptions into his theory. He left a huge and complicated legacy which needs to be examined and picked through with care. My aim in these reviews is not to endorse his opinions but to summarise his writings, adding my own thoughts and comments as they arise.

***

In the realm of fiction we find the plurality of lives which we need.

(Thoughts on War and Death, Pelican Freud Library volume 12, page 79)

Introduction

Volume 14 of the Freud Pelican Library pulls together all of Sigmund Freud’s essays on art and literature.

From my point of view, as a one-time student of literature, one of the most obvious things about all Freud’s writings, even the most ostensibly ‘scientific’, is that he relies far more on forms of literature – novels, folk tales, plays or writers’ lives – than on scientific data, data from studies or experiments, to support and elaborate his theories.

In my day job I do web analytics, cross-referencing quantitative data from various sources, crunching numbers, using formulae in spreadsheets, and assigning numerical values to qualitative data so that it, too, can be analysed in numerical terms, converted into tables of data or graphical representation, analysed for trends, supplying evidence for conclusions, decisions and so on.

So far as I can tell, none of this is present at all in Freud’s writings. A handful of diagrams exist, scattered sparsely through the complete works to indicate the relationship of superego, ego and id, or representing the transformation mechanisms of wishes which take place when they’re converted into dream images, repressed, go on to form the basis of compromise formations, and so on. But most of Freud is void of the kind of data and statistics I associate with scientific writing or analysis.

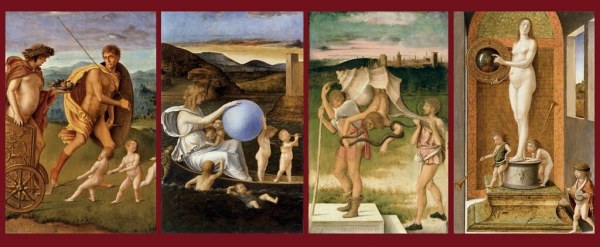

Instead Freud relies very heavily indeed on works of fiction and literature, folk tales and fairy tales, the myths and legends of Greece and Rome, anecdotes and incidents in the lives of great writers or artists (Goethe, Leonardo).

Right from the start Freud’s writings provided a new model for literary, artistic and biographical interpretation and so it’s no surprise that psychoanalytical theory caught on very quickly in the artistic and literary communities, and then spread to the academic teaching of literature and art where it thrives, through various reversionings and rewritings (Lacan, feminist theory) to this day.

It’s probably too simplistic to say psychoanalysis was never a serious scientific endeavour; but seems fair to say that, in Freud’s hands, it was always an extremely literary one.

What follows is my notes on some, not all, of the essays contained in Volume 14 of the Freud Pelican Library.

1. Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s ‘Gradiva’ (1907)

It was Jung, a recent convert to psychoanalysis, who brought this novel, Gradiva, by the German novelist Wilhelm Jensen, published 1903, to Freud’s attention. It is the story of an archaeologist, Norbert Hanold, who comes across an ancient bas-relief of a girl who is walking with a distinctive high-footed step. He names her ‘Gradiva’, which is Latin for ‘light-tripping’, and becomes obsessed with the image.

Cast relief of ‘Gradiva’ (1908), which, as a result of Freud’s essay on the novel, he bought and hung on his study wall

It comes into Hanold’s head that the relief is from Pompeii and that he will somehow meet the girl who is the model for it if he goes there. So off to Pompeii he goes and, one summer day, walking among the ruins, comes across an apparition, a hallucination, of the self-same girl!

They talk briefly and then she disappears among the ruins but not before displaying the unique walk depicted in the frieze. A second time he meets her and their talk clears his muddled mind. Over subsequent meetings and conversations it becomes clear that she is the girl who lives across the road from him in Berlin, named Zoe Bertgang, and whom he loved playing with as a boy.

What happened is that, at puberty, Hanold became obsessed with archaeology and, in his pursuit of it, rejected normal social activity, including with the opposite sex. He repressed and forgot his childhood love for Zoe, redirecting his energies, sublimating them, into an abstract love of Science. But, despite the best efforts, the repressed material returned, but in a garbled censored form, as his irrational unaccountable obsession with this carving.

Over the course of their meetings, Zoe slowly pulls him out of what is clearly some kind of nervous breakdown, eliminating all the voodoo and hallucinatory significances which he had accumulated around the relief; makes him realise she is just an ordinary girl, but one he has continued to be in love with.

Through her long and patient conversations, through talking through his odd symptoms and obsessions, he is slowly returned to ‘normality’, ‘reality’, and to a conventional loving relationship with a young woman. And so they get engaged.

This novel could almost have been written expressly to allow Freud to deploy his favourite themes. For a start it contains many of Hanold’s, dreams which Freud elaborately decodes, thus reaffirming the doctrine that dreams are ‘the royal road to the unconscious’. Confirming the theories put forward in The Interpretation of Dreams that during sleep the censorship of feelings and complexes which are rigorously repressed during conscious waking life, is relaxed, allowing deep wishes to enter the mind, albeit displaced and distorted into often fantastical imagery.

It allows Freud to reiterate his theory that the mind is comprised of two equal and opposite forces which are continually in conflict – the Pleasure Principle which wants, wishes and fantasises about our deepest desires coming true, sometimes in dreams, sometimes in daydreams or fantasies, sometimes in neurotic symptoms and mental disturbances – because it is continually struggling to get past the repressing force of the Reality Principle.

Dreams, like the symptoms of the neurotic and obsessive patients Freud had been treating since the 1980s, are compromises between these two forces. Thus the hero of the novel, Norbert Hanold, is a timid man whose profession of archaeologist has cut him off from the flesh and blood world of real men and women.

This division between imagination and intellect destined him to become an artist or a neurotic; he was one of those whose kingdom was not of this world.

But, in Freudian theory, the unconscious wishes often return from the place where they are most repressed, at the point of maximum defence. Hence it was precisely – and only – from the dry-as-dust, academic world of archaeology, where he had fled from the real world, that the repressed feelings could return in the form of a two thousand year-old relief – that Hanold’s real passion for the flesh-and-blood girl who lives across the road, can emerge.

There is a kind of forgetting which is distinguished by the difficulty with which the memory is awakened even by a powerful external summons, as though some internal resistance were struggling against its revival. A forgetting of this type has been given the name of repression in psychopathology.

Norbert seeks for Gradiva in Pompeii, driven there by increasingly delusive fantasies. Freud explains these as the last desperate attempts of the Censor to flee the unconscious wish to sexually possess the girl he has loved since his childhood, but, fearing her sexuality, fearing his own untrammeled sexuality, has blocked, repressed and sublimated into a love for his passionless, ‘scientific’ profession’, archaeology. The repressed always returns. You can run but you can’t hide.

It is an event of daily occurrence for a person – even a healthy person – to deceive himself over the motives for an action and to become conscious of them only after the event…

[Hanold]’s flight to Pompeii was a result of his resistance gathering new strength after the surge forward of his erotic desires in the dreams [Norbert is plagued by obscure passionate dreams which Freud analyses as sex-dreams]. It was an attempt at flight from the physical presence of the girl he loved. In a practical sense, it meant a victory for repression…

Except that it is precisely in Pompeii, with a kind of dreamy, Expressionistic logic, that Hanold runs into the very girl he’s gone all that way to escape, and who initially presents herself as the living incarnation of the 2,000 year-old relief.

Only slowly does the truth dawn on Norbert (and the reader) and his secret desires become revealed to him, even as he slowly realises this is a real flesh-and-blood girl and not some spirit, a girl who reveals her name to be Zoe, Greek for ‘life’.

The entire novel turns, in Freud’s hands, into another one of his case studies: Hanold is an obsessive neurotic suffering from bad dreams and delusions; Zoe is in the unique position of being both his repressed love-object and his psychoanalyst. She practises the ultimate ‘cure through love’ by tenderly returning Hanold to a correct understanding of Reality, of who he is, who she is, and the true nature of his feelings for her.

How was Hanold able to go along in the grip of his powerful delusions for so long?

It is explained by the ease with which our intellect is prepared to accept something absurd provided it satisfies powerful emotional impulses…

After all, Freud writes, in one of the many, many comparisons with religious beliefs and ways of thinking which litter his writings:

It must be remembered too that the belief in spirits and ghosts and the return of the dead which finds so much support in the religions to which we have all been attached, at least in our childhood, is far from having disappeared among educated people, and that many who are sensible in other respects find it possible to combine spiritualism with reason.

The Gradiva story allows Freud to elaborate on the link between but contrast between belief and delusion:

If a patient believes in his delusion so firmly, this is not because his faculty of judgement has been overturned and does not arise from what is false in the delusion. On the contrary there is a grain of truth concealed in every delusion, there is something in it which really deserves belief, and this is the source of the patient’s conviction, which is therefore to this extent justified.

This true element, however, has long been repressed. If eventually it is able to penetrate into consciousness, this time in a distorted form, the sense of conviction attaching to it is overintensified as though by way of compensation and is now attached to the distorted substitute for the repressed truth, and protects it from any critical attacks.

The conviction is displaced, as it were, from the unconscious truth on to the conscious error that is linked to it, and remains fixated there precisely as a result of this displacement.

The method described here whereby conviction arises in the case of a delusion does not differ fundamentally from the method by which a conviction is formed in normal cases. We all attach our conviction to thought-contents in which truth is combined with error and let it extend from the former over into the latter. It becomes diffused, as it were, from the original truth over onto the error associated with it, and protects the latter.

So in Gravida the dry, repressed Norbert is awakened from his dream-delusion of worship for a stone relief he has named Gradiva, into the reality of his long-lost childhood love for the flesh-and-blood woman Zoe:

The process of cure is accomplished in a relapse into love, if we combine all the many components of the sexual instinct under the term ‘love’; and such a relapse is indispensable, for the symptoms on account of which the treatment has been undertaken are nothing other than the precipitates of earlier struggles connected with repression or the return of the repressed, and they can only be resolved and washed away by a fresh high tide of the same passions. Every psychoanalytic treatment is an attempt at liberating repressed love which has found a meagre outlet in the compromise of a symptom.

So influential was Freud’s essay on Gradiva as suggesting and exemplifying a whole new way of reading and thinking about literature, that it became a cult, many of the early psychoanalysts carried round small models of the Gradiva relief and Freud had a full-scale replica hanging in his office (still viewable at the Freud Museum).

2. Psychopathic stage characters (1906)

Art allows for the vicarious participation of the spectator. When we read a poem we feel spiritually richer, subtler, nobler than we are. When we watch a play we escape from the confines of our dull cramped lives into a heroic career, defying the gods and doing great deeds. The work of art allows the spectator an increase, a raising of psychic power.

Lyric poetry serves the purpose of giving vent to intense feelings of many sorts – just as was once the case with dancing. Epic poetry aims chiefly at making it possible to feel the enjoyment of a great heroic character in his hour of triumph. But drama seeks to explore emotional possibilities more deeply and to give an enjoyable shape even to forebodings of misfortune; for this reason it depicts the hero in his struggles and, with masochistic satisfaction, in his defeats.

For Freud, crucially, human nature is based on rebellion:

[Drama] appeases, as it were, a rising rebellion against the divine regulation of the universe, which is responsible for the existence of suffering. Heroes are first and foremost rebels against God or against something divine.

We like to watch the hero rise, as a thrilling personification of the resentment we all feel against the limitations of Fate – and then to fall, after a brief heroic career, because their fall restores order and justifies our own craven supineness in relation to the world.

Freud likes the Greek dramatists because they openly understood and acknowledged the power of this: life is a tragic rebellion against Fate. The Greek view of life, essentially tragic – from Homer to Aeschylus – contrasted with the essentially rounded, optimistic view of the theisms, Judaism and Christianity, in which suffering may be pushed to its limit – Job, Jesus – but brings with its new understanding and even salvation.

Christianity takes an essentially comic, non-tragic view of the world; Jesus came to save us, to fulfil the Law, and in his torture, crucifixion and death we partake of a Divine Comedy of despair and renewal. With his resurrection the circle is complete. But there is no renewal in Greek tragedy. Neither Oedipus nor Thebes are renewed or improved.

The two worldviews deal with the same subject matter, and overlap in the middle, but from fundamentally opposed viewpoints.

Freud likes the Greeks because of their acknowledgment of the tragic fate of man: his later writings are loaded with references to Ananke and Logos, the twin gods of Necessity and Reason by which we must lead our lives.

Freud dislikes Christianity because it sets out to conceal this truth, to offer redemption, eternal life, Heaven, the punishment of the guilty and the salvation of the Good. It offers all the infantile compensations and illusions he associates with the weakest of his patients. It is intellectually and emotionally dishonest. It says the greatest strength is in submission to the Will of God, turning the other cheek, loving your neighbour as yourself.

As a good Darwinian Freud acknowledges that these standards may be morally admirable but, alas, unattainable for most, if not all of us mortals. In his view Christianity forced its adherents into guilt-ridden misery or to blatant hypocrisy. (Interestingly, it was actually Jung who, in their correspondence, called the Church ‘the Misery Institute’.)

Freud moves on to outline an interesting declension in the subject matter of drama:

Greek tragedy must be an event involving conflict and it must include an effort of will together with resistance. This precondition finds its first and grandest fulfilment in the struggle against divinity. A tragedy of this sort is one of rebellion, in which the dramatist and the audience takes the side of the rebel.

The less belief there comes to be in divinity, the more important becomes the human regulation of affairs; and it is this which, with increasing insight, comes to be held responsible for suffering. Thus the hero’s next struggle is against human society and here we have the class of social tragedies.

Yet another fulfilment of the necessary precondition is to be found in a struggle between individual men. Such are tragedies of character which display all the excitement of a conflict and are best played out between outstanding characters who have freed themselves from the bond of human institutions….

After religious drama, social drama and the drama of character we can follow the course of drama into the realm of psychological drama. Here the struggle that causes the suffering is fought out in the hero’s mind itself – a struggle between different impulses which have their end not in the extermination of the hero but in the victory of one of the impulses; it must end, that is to say, in renunciation…

For the progression religious drama, social drama, drama of character and psychological drama comes to a conclusion with psychopathological drama, hence the title of the essay. Psychological drama is where the protagonist struggles in his mind with conflicting goals, desires, often his personal love clashing with social values etc. Psychopathological drama is one step further, where the conflict takes place within the hero’s mind, but one side or aspect or impulse is repressed. It is the drama of the repressed motive, in which the protagonist demonstrates the symptoms Freud had written about in neurotic, namely that they are in the grip of fierce compulsions or anxieties but don’t know why.

The first of these modern dramas is Hamlet in which a man who has hitherto been normal becomes neurotic owing to the peculiar nature of the task by which he is faced, a man, that is, in whom an impulse that has been hitherto successfully repressed endeavours to make its way into action [the Oedipus impulse].

The essay repeats the interpretation Freud first gave of Hamlet in The Interpretation of Dreams, namely that the reason for Hamlet’s long delay in carrying out vengeance against his uncle is because his uncle has acted out Hamlet’s Oedipal dream – he has murdered his (Hamlet’s) father and bedded his (Hamlet’s) mother. This is the deep sexual fantasy which Freud posits at the core of the development of small boys and labelled the Oedipus complex, and Claudius has done it for Hamlet; he has lived out Hamlet’s deeply repressed Oedipal fantasy, and this is why Hamlet can’t bring himself to carry out the revenge on his uncle which his conscious mind knows to be just and demanded by social convention: it’s because his uncle has carried out Hamlet’s repressed Oedipal fantasy so completely as to have become Hamlet, on the voodoo level of the unconscious to be Hamlet. To kill his uncle would be to kill the oldest, most deeply felt, most deeply part of his childhood fantasy. And so he can’t do it.

I studied Hamlet at A-level and so know it well and know that Freud’s interpretation, although it initially sounds cranky and quite a bit too simplistic and glib – still, it’s one of the cleverest and most compelling interpretations ever made of the play.

Anyway, in this theoretical category of psychopathological drama, the appeal to the audience is that they, too, understand, if dimly, the unexpressed, repressed material which the protagonist is battling with. If in the tragic drama of the ancients the hero battles against the gods, at this other end of the spectrum, in modern psychopathological drama, the hero fights against the unexpressed, unexpressible, repressed wishes, urges, desires, buried beyond recall in his own unconscious.

3. Creative writers and daydreams (1907)

In this notorious essay Freud tries to psychoanalyse the foundation of creative writing but he’s notably hesitant. It’s a big subject and easy to look foolish next to professional critics and scholars. Hence Freud emphasises that he is only dealing with the writers of romances and thrillers i.e. anything with a simple hero or heroine or, to put it another way, which are simple enough for his psychoanalytical interpretation to be easily applied.

So: A piece of creative writing is a continuation into adulthood of childhood play. (The English reader may be reminded of Coleridge’s comment that the True Poet, as exemplified by his friend Wordsworth, is one who carries the perceptions of childhood into the strength of maturity.)

A piece of creative writing, like a day-dream, is a continuation of, and a substitute for, what was once the play of childhood.

Children play by recombining elements of the outside world into forms and narratives which suit their needs. As we grow up we stop overtly playing but Freud suggests that we never give up a pleasure once experienced and so we replace physically real playing with a non-physical, purely psychical equivalent, namely fantasising.

Childhood play is public and open but most people fantasise in private, in fact they’re more willing to admit to doing wrong than to confessing their fantasies. The child more often than not wants to be ‘grown up’; whereas many adults’ fantasies are childish in content or expression.

Now Freud steps up a gear and begins to treat fantasies as if they were dreams, in that he insists that ‘every single fantasy is the fulfilment of a wish, a correction of unsatisfying reality’. Each fantasy refers back to a childhood wish, attaches it to images or experiences in the present, and projects it into a future where it is fulfilled.

A work of art gathers its creative strength from the power of childhood recollections, for example Gradiva, centred on dreams and delusions powered by childhood erotic experiences.

At about this point it becomes clear that these ‘fantasies’ have a very similar structure to the dreams which Freud devoted such vast effort to interpreting in his book of the same title. Which is why everyday language in its wisdom also calls fantasies ‘day dreams’. So ‘day’ dreams and ‘night’ dreams are very similar in using imagery provide by the events of the day to ‘front up’ unexpressed, often repressed wishes.

Thoughts

The big flaw in this theory is, How do you deal with the fact that most of the literature of the ancients and of the Middle Ages consists of recycled stories, metaphors, even repeated lines i.e. are not the packaging of anyone’s childhood recollections but traditional narratives?

Freud says:

- the artist still makes decisions about how to order his material and these decisions are susceptible to psychoanalysis

- folk tales and myths i.e. recurrent stories, may themselves be seen as the wishful fantasies or the distorted childhood reminiscences of entire nations and peoples and be psychoanalysed accordingly

(Regarding the origin of myths, in a letter to his confidant Wilhelm Fliess, in 1897, Freud had written: ‘Can you imagine what endopsychic myths are? They are the offspring of my mental labours. The dim inner perception of one’s own psychical apparatus stimulates illusions of thought, which are naturally projected outwards and characteristically onto the future and the world beyond. Immortality, retribution, life after death, are all reflections of our inner psyche… psychomythology.)

The ‘voyeuristic theory’ outlined by Freud in Psychopathic Stage Characters, and this essay, would say the libidinal satisfaction to be achieved through watching or reading the literary work remains the same – the vested interest of the reader\spectator in vicariously rising above their dull every day lives – regardless of formal considerations. But there’s still a substantial objection which is, Why do we prefer some versions of a traditional story over others?

Freud is forced to concede the existence of a ‘purely formal – that is, aesthetic – yield of pleasure’ about which psychoanalysis can say little in itself.

The writer softens the character of his egoistic daydreams by altering and disguising it, and he bribes us by the purely formal – that is, aesthetic – yield of pleasure which he offers us in the presentation of his phantasies. We give the name of fore-pleasure to a yield of pleasure such as this which is offered to us so as to make possible the release of still greater pleasure arising from deeper psychic sources.

In my opinion all the aesthetic pleasure which a creative writer affords us has the character of a fore-pleasure of this kind, and our actual enjoyment of an imaginative work proceeds from a liberation of tensions in our minds.

Thus he has divided literary pleasure into two parts:

- fore-pleasure ‘of a purely formal kind’, ‘aesthetics’

- the deeper pleasure of psychic release, the cathartic release of libidinal energy

This is very similar in structure to his theory of jokes (as laid out in the 1905 work ‘Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious’). In this aesthetic, formal fore-pleasure – the structure of a limerick, the shape of a joke – is a pretext for the joke’s real work – the release of frustration, pent-up pressure, libido.

Critics argue that claiming the core purpose of art to be libidinal release – if the basic point of all art is some kind of psychosexual release – fails to acknowledge that the main thing people talk about when they discuss art or plays or books, the plot and characters and language, are secondary ‘aesthetic’ aspects. It is precisely the artfulness, the creative use the writer makes of traditional material, which is of interest to the critic and to the informed reader, upon which we judge the author, and it is this very artfulness which Freud’s theory leaves untouched. Which is to say that Freudianism has little to do with pure literary criticism.

Freudian defenders would reply that psychoanalysis helps the critic to elucidate and clarify the patterns of symbolism and imagery, the obsessions and ideas, which are crafted into the work of art. This clearly applies most to modern artists who think they have a personal psychopathology to clarify (unlike, say, Chaucer or Shakespeare, who focused on reworking their traditional material).

In practice, literary critics, undergraduates and graduate students by the millions have, since the publication of this essay, gone on to apply Freudian interpretations to every work of art or literature ever created, precisely be applying Freudian decoding to the formal elements of narratives which Freud himself, in his own essays, largely overlooked.

4. Leonardo da Vinci and a memory of his childhood (1910)

Leonardo could never finish anything. Freud says this was because he was illegitimate i.e. abandoned by his rich father and left with his peasant mother for years. This prompted two things: a sublime sense of the total possession of his mother without the rivalry of Daddy which is captured in his best art, for example the Mona Lisa; and a restless curiosity about where he came from.

These latter childhood sexual enquiries were sublimated into his scientific work, into his wonderful studies of Nature and its workings. But also explains why ,whenever he tried to do a painting, he ended up trying to solve all the technical problems it raised, and these problems raised others, and so on.

A good example is his trying to devise a way of doing frescoes with oil. It was his botched technical experiments in this medium which means the famous Last Supper has slowly fallen to pieces.

Observation of men’s daily lives shows us that most people succeed in directing very considerable portions of their sexual instinctual forces to their professional activity. The sexual instinct is particularly well-fitted to make contributions of this kind since it is endowed with a capacity for sublimation: that is, it has the power to replace its immediate aim by other aims which may be valued more highly and which are not sexual.

Freud turns Leonardo into a paradigmatic homosexual: a boy abandoned by his father and left too long under the influence of his mother who, in repressing his love for his mother, takes her part, introjects her into his psyche, identifies wholly with her and comes to look upon love-objects as his mother would i.e. looks for young boys whom he can love as his mother loved him. In a sense a return to auto-eroticism or narcissism.

Freud then uses his theory of Leonardo’s homosexuality to interpret the later figures in his paintings (for example, John the Baptist) as triumphs of androgyny, reconciling the male and female principles in a smile of blissful self-satisfaction.

Freud speculates that Mona Lisa re-awakened in Leonardo the memory of his single mother, hence the ineffable mystery of her smile – and Leonardo’s inability to finish the painting, which was never delivered to the patron, Mona’s husband, and so he ended up taking to the French court, where it was bought by King Francis I which is why it ended up hanging in the Louvre.

So Leonardo’s actual artistic technique, the extraordinary skill which produced the Mona Lisa smile, is merely a fore-pleasure, a pretext, a tool to draw us into what Freud sees as the real purpose of art, the libidinal release, in this case drawing us into sharing the same infantile memory of erotic bliss, of total possession of mummy, that Leonardo was expressing.

At the heart of this long essay is a dream Leonardo recorded in a notebook.

Leonardo dreamed that a vulture came into his room when he was a child and stuck its tail into his mouth. Freud says Leonardo would have known that the vulture was the Egyptian hieroglyph for ‘Mother’ and so the dream represents a deep memory of his infantile happiness at the total possession of his Mummy.

The only problem with this, as Peter Gay and the editors of the Freud Library point out, is that the word ‘vulture’ is a mistranslation in the edition of Leonardo’s notebooks which Freud read; the original Italian word means kite, a completely different kind of bird.

So a central plank on which Freud had rested a lot of his argument in this long essay is destroyed in one blow. But Freud never acknowledged the mistake or changed the passage and so it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that this is simple charlatanry, that Freud, here as in many other places, could not change mistakes because they were vital means which enabled him to project the powerful personal obsession which he called psychoanalysis out onto the real world. That, somehow, it was all or nothing. No gaps or retractions were possible lest the entire edifice start to crumble.

Leonardo is important to Freud because he was the first natural scientist since the Greeks. If Authority is the Father and Nature the Mother, then his peculiar fatherless upbringing also helps to explain Leonardo’s refusal to rely on ‘authorities’, and his determination to wrest the mysteries of Nature for himself, a rebellion against father and quest for total possession of mother which has clear Oedipal origins.

His later scientific research with all its boldness and independence presupposed the existence of infantile sexual researches uninhibited by the father…

This is an illuminating insight. But when, a few pages later, Freud says dreams of flying are all connected with having good sex, and Leonardo was obsessed with birds and flying machines because scientific enquiry stems from our infantile sexual researches, you begin to feel Freud is twisting the material to suit his ends.

This is even more the case in Freud’s treatment of Leonardo’s father. First we are told that not having a Dad helped Leonardo develop a scientific wish for investigation; then that having a father was vital to his Oedipal ‘overthrowing’ of Authority and received wisdom; then that Leonardo both overcame his father who was absent in his infancy and became like him insofar as he tended to abandon his artistic creations half-finished, just like Ser Piero (his dad) had abandoned him.

Freud is trying to have it all ways at once. A feeling compounded by moments of plain silliness: for example when Freud claims his friend Oskar Pfister found the outline of a vulture in the painting of St Ann with Jesus, or when Freud points out that a sketch of a pregnant woman from the notebook has wrong-way round feet, thus suggesting… homosexuality! In the notes we are told the feet look odd because they were, in fact, added in by a later artist. The net result of all these errors and distortions is that, by now, Freud is looking like a fool and a charlatan. The whole thing is riddled with errors.

Conclusion

Freud is like a novelist who scatters insights around him concerning the tangles, complexities, repressions and repetitions of human life with which we are all familiar – now that Freud has pointed them out to us. But whenever he tries to get more systematic, more ‘scientific’, he gets more improbable.

The insights into Leonardo’s psychology are just that, scattered insights. But when he tries to get systematic about infantile sexual inquiry or the origins of homosexuality, you feel credulity stretched until it snaps. It comes as no surprise to learn that the whole extended vulture-dream argument, which reeks of false scholarship and cardboard schematicism, has been shown to be completely wrong.

All the same, no less an authority than art historian Kenneth Clark said that, despite its scholarly errors, Freud’s essay was useful in highlighting the difference, the weirdness of Leonardo. This is the eerie thing about Freud: even when he’s talking bollocks, even when he’s caught out lying, his insights and his entire angle of vision, carry such power, ring bells or force you to rethink things from new angles, and shed fresh light.

5. The theme of the three caskets (1913)

This is an odd little essay on the three-choices theme found in many folk-tales, myths and legends. Freud concentrates on its manifestation in the Shakespeare plays, The Merchant of Venice and King Lear.

The Prince in Merchant wisely picks lead, rather than silver or gold, and thus wins the hand of Portia. Lear foolishly picks worldly things – Goneril and Regan’s sycophancy – and rejects Cordelia’s true love.

What Freud can now ‘reveal’ is that Cordelia and Lear really symbolise DEATH! By refusing his own death – i.e. his inevitable fate – Lear wreaks havoc on the natural order: a man must accept his death.

For the three caskets are symbols of the fundamental three sisters, the Norns of Norse, and the Fates of Greek mythology. The third Fate is Atropos or Death and so picking the third, the least attractive of three choices, is, in fact, to pick death.

Hang on, though: what about the classical story of the judgement of Paris? Paris gives the apple to Aphrodite, goddess of Love. Freud raises this objection only to smoothly deal with it: it’s because Man’s imagination, in rebellion against Fate, converts, in the Paris-myth, the goddess of Death into the goddess of Love, unconsciously turning the most hateful thing into the most loveful thing: it is one more example of the unconscious reversing polarities and making opposites meet.

The Fates were created as a result of the discovery that warned man that he too is a part of nature and therefore subject to the immutable law of death. Something in man was bound to struggle against this subjection, for it is only with extreme unwillingness that he gives up his claim to an exceptional position.

Man, as we know, makes use of his imaginative activity in order to satisfy the wishes that reality does not satisfy. So his imagination rebelled against the recognition of the truth embodied in the myth of the Fates and constructed instead, the myth derived from it, in which the goddess of Death is replaced by the goddess of Love.

This essay is a brilliant example of the weird, perverse persuasiveness of Freud’s imagination and a deliberate addition to the variety of strategies psychoanalysis has for literature:

- to the psychoanalysis of plot: Gradiva

- the psychoanalysis of artist’s character: Leonardo (above), Dostoyevsky (below)

- the psychoanalysis of myth-symbolism: the three caskets

- the psychoanalysis of the act of creation itself, what it does, what it’s for: Creative Writers and Daydreaming

- the psychoanalysis of the history of a genre: Psychopathic stage characters (above)

When you list them like this you realise the justice of Freud’s self-description as a conquistador. He deliberately set out to conquer all aspects of all the human sciences – art, literature, anthropology, sociology, history – to which his invention could possibly be applied, and he was successful.

6. The Moses of Michelangelo (1914)

It has traditionally been thought that Michelangelo’s imposing statue of Moses in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli depicts the leader of the Israelites having come down from the mountain with the tablets of the commandments only to see the Israelites dancing round the Golden Calf and to be about to leap up in wrath.

Freud completely reverses this view. Freud turns this Moses into a model of Freud’s idea of self-overcoming or the Mastery of Instinct:

The giant figure with its tremendous physical power becomes only a concrete expression of the highest mental achievement that is possible in a man, that of struggling successfully against an inward passion for the sake of a cause to which he has devoted himself.

This essay was written in 1914 just after the split with Freud’s disciples, Carl Jung and Alfred Adler, leaving Freud feeling bitter and angry. They thought they were rebelling against a stifling father figure who insisted on blind obedience to his theory and diktats. He thought he had given them a world of new insights, as well as personal help and support, only to watch them distort and pervert his findings for their own ends, to further their own careers.

You don’t have to be a qualified psychiatrist to speculate that there might be a teeny-weeny bit of self-portraiture in Freud’s interpretation of Moses: a heroic passionate man, founder of a whole new way of seeing the world, much-wronged by those he cared for, heroically stifling his justifiable feelings of anger and revenge. There is much in Moses for Freud to identify with.

Overcoming, this is Freud’s perennial theme: civilised man’s continual attempt to master his animal nature. It’s at its clearest here in his interpretation of Moses’ superhuman restraint but it runs like a scarlet thread through his work, eventually blossoming into full view in Civilisation and Its Discontents.

On the way to achieving the heroic self-denial which we call ‘civilisation’ the poor human animal takes many wrong turns and false steps: these are the illnesses, the neuroses, the hysterias and perversions which Freud spent the early part of his career discussing (see in particular, Three Essays On Sexuality 1905).

But even when you have achieved self-mastery, even if your development works out well and you rid yourself of your neuroses and arrive at a mature, adult morality, disenchanted from willful illusions like religious belief and personal superstition, all this heroic self-mastery only brings you face-to-face with a bigger problem: Fate and Death. How can you cope with this final insult to the narcissistic self-love which, despite all your conscious better intentions, nonetheless guides your actions?

Freud suggests a variety of strategies:

- falling ill: the ‘flight into illness’ identified as early as 1895 in his book on hysteria

- killing yourself: the superego’s rage against the failure of the ego to master reality

- rebellion against fate: as epitomised by all the heroes of myth and legend, which Freud identifies the core subject of heroic (Greek) tragedy

- sublimating unconscious panic-fear into its opposite, exaggerated submission and masochistic greeting of the blows of Fate (as in some types of submissive religious belief)

- outstaring Death with a calm rational stoicism (Freud’s view of himself)

But art, too, has a place among these responses. Art either:

- provides parables and models which help us come to terms with illness and death and Fate (as Gradiva is a model of the psychoanalytic cure; the three caskets are fairy tales which help us, unconsciously, to accept the inevitable)

- or helps us to rise emotionally above our narrow, cramped lives (as explained in Creative Writers and Psychopathic stage characters)

Or:

- is the product of compulsions, obsessions and neuroses on the part of the artist (for example, Leonardo) for whom art acts as therapy and whose purely personal solutions to these problems may appeal to our own situation, and in some way reconcile us to our own fate

- or simply evoke pleasant unconscious memories, for example the blissful mood conveyed by the smiles of the Mona Lisa or St John the Baptist

Art may leave us with a tantalising sense of mystery and transcendence; or it may thrill us with the spectacle of an artist grappling with feelings he barely understands, feelings and struggle which the art work makes us feel and sympathise with.

9. A childhood recollection from Dichtung Und Wahrheit (1917)

Dichtung Und Wahrheit was the title of the autobiography of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the great German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. Goethe was Freud’s lifelong favourite writer and Freud is liable to drop a Goethe quote into any of his essays at the drop of a hat.

One of the first anecdotes in Goethe’s autobiography describes the little poet, aged about three, throwing all the crockery in the house out into the street and chuckling as it smashed.

Freud shows, by citing comparable stories told by his patients, that this was an expression of Goethe’s jealousy and hatred of his new young brother who had just been born and threatened to supplant him in his mother’s affections. The brother later died and Goethe was, unconsciously, happy. So, in Freud’s hands, this inconsequential anecdote turns out to be a vital key to Goethe’s personality:

I raged for sole possession of my mother – and achieved it!

As with Moses, the autobiographical element in Freud is large. As he says in his own autobiography:

A man who has been the indisputable favourite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror, that confidence of success which often induces real success.

Compare with the way the ‘secret’ of Leonardo turned out to be the unquenchable if unconscious bliss he kept all his life of having possessed his mother’s love, undiluted by the absent father. The fact that so many of Freud’s insights turn out so nakedly to be repetitions of key aspects of his own personality prompts the $64,000 question: Are Freud’s insights into human nature the revelation of universal laws? Or a mammoth projection onto all mankind of his own idiosyncratic upbringing and personality?

10. The Uncanny (1919)

This is the first of these essays to be written under the influence of Freud’s second, post-Great War, theory of psychoanalysis. The new improved version was a great deal more complicated than earlier efforts.

This essay is an attempt to apply the symbolic mode of interpretation to the E.T.A Hoffman story of ‘Olympia and the Sandman’ in which several ‘doubles’ appear, creating an ‘uncanny’ effect.

For post-war Freud the human psyche is dominated by a compulsion to repeat: this is the secret of the anxiety dreams of shell-shock victims, or of the child’s repetitive games, discussed at such length in Beyond The Pleasure Principle, 1920.

An aspect of this profound human tendency to repeat is the idea of ‘doubles’. Beginning with the notion of the ‘soul’ – the Christian idea that we are made of two things, a body and a soul – doubles in various forms litter human culture.

Freud speculates that the role of doubles is to:

- stave off death: you have a secret double fighting on your behalf, a good fairy, a good angel etc

- underpin ideas of free will, of alternative actions which you could, but didn’t take

- become, by reversal, objects of aggression and fear, doubles which return as harbingers of doom in fairy stories and in neurotic hallucinations

After this little detour Freud gets to the point: the uncanny is the feeling prompted by the return of the childish belief in the omnipotence of thoughts.

For example, you think of someone and the next minute the phone rings and it’s them on the line. You experience an ‘uncanny’ sensation because, for a moment, you are back in the three year old’s narcissistic belief that the universe runs according to your wishes.

And the eruption into your tamed adult conscious of this primitive, long-repressed idea prompts a feeling of being ‘spooked’, unsettled – the Uncanny.

When someone has an ‘uncanny’ knack of doing something it’s the same: it makes us feel weird because their consistent success reminds us of our infantile fantasies of immediate wish-fulfilment and gratification; the powerful wish to be able to do something effortlessly and easily which possessed us as children but which we had to painfully smother and put behind us in order to cope with the crushingly ungratifying nature of reality.

In the broadest sense the uncanny is the return of the repressed: the Oedipus Complex, the omnipotence of thoughts, the obsession with doubles, even return to the womb feelings: they are strange, disturbing, but ultimately not terrifying because we have felt them before.

11. A seventeenth century demonological neurosis (1923)

Freud’s interest in witchcraft, possession and allied phenomena was of longstanding, possibly stimulated by his trip to the Salpetriere Hospital to study under Charcot in 1885.

Freud’s ‘Report’ on his trip mentions that Charcot paid a great deal of attention to the historical aspects of neuroses i.e. to tales of possession and so on.

The series of lectures of Charcot’s which Freud translated into German includes discussion of the hysterical nature of medieval ‘demono-manias’ and an account of a sixteenth century case of demonic possession.

It is recorded that in 1909 Freud spoke at length to the Vienna Society on the History of the Devil and of the psychological composition of belief in the Devil.

In mentioning ‘the compulsion to repeat’ in The Uncanny (a phenomenon dealt with at length in Beyond The Pleasure Principle and vitally important for understanding Freud’s later theory) Freud says:

It is possible to recognise the dominance in the unconscious mind of a ‘compulsion to repeat’ proceeding from the instinctual impulses and probably inherent in the very nature of the instincts – a compulsion powerful enough to overcome the pleasure principle, lending to certain aspects of the mind their demonic character, and still very clearly expressed in the impulses of young children, a compulsion too which is responsible for the course taken by the analyses of neurotic patients.’

Here we have the first glimmerings of the set of ideas which were to crystallise around the new concept of the superego, namely that it is the agent of the death drive, the fundamental wish of all organisms to return to an inorganic state of rest.

The superego channels this drive through the introjection (or internalisation) of the infantile image of our demanding parents, who continue to demand impossible standards all our lives and, when we fail to live up to them, harry us, persecute us, make us feel guilty, anxious, or depressed, filled with self-hatred and self-loathing.

One aspect of this is what earlier ages called ‘possession’, when people heard voices or seemed impelled to do what they didn’t want to. This impelling comes from the id, from our dumb, voiceless instincts – but the self-reproaches for having stepped out of line come from the superego, which, in some circumstances, exaggerates the fairly common guilt at our ‘sinfulness’ into florid ideas of demonic possession.

The essay is a psychoanalysis, using these new concepts, of the historical case of one Christopher Haizmann, a painter in the seventeenth century who fell into a melancholy at the death of his father and then claimed to the authorities that he had signed a pact with the Devil. The historical sequence of events is that he eventually renounced his pact and was looked after for a while by the Christian Brothers.

Freud diagnoses Haizmann as Grade A neurotic. Upon his father’s death he was prompted to review his life and realised he was a failure, a good-for-nothing. The pacts he reports himself as making, bizarrely, ask the Devil to take him as His son. Haizmann is transparently looking for a father-substitute who will punish him for his perceived failure.

More subtly, then, Haizmann is inflating the punitive superego (based on infantile memories of his father) into the grand figure of Devil, the bad or punitive father.

Unfortunately, upon re-entering the world, Haizmann suffered a relapse. He claimed to be the victim of an earlier pact he signed with the Devil and, for some reason, forgot about. Once more he renounced it upon being readmitted to life with the Christian Brothers, but this time he renounced the world also and spent the rest of his life with them.

The devil is the bad side of the father i.e. the child’s projection of his ambivalent feelings onto an ego-ideal. Sociologically speaking, in the history of religion, ‘devils’ were old gods who we have overcome and onto whom we then project all our suppressed lust and violence. So Baal was a perfectly decent Canaanite god until the Israelites overthrew the Canaanites in the name of their god, Yahweh, at which point the Israelites projected onto Baal him all the wickedness and lust in their own hearts. Satan, in Christian doctrine, was originally the brightest and best of God’s angels, before a similar process of overthrow and then being scapegoated with all our worst imaginings. So the devil is the father-figure we have overcome in fantasy, but onto whom we then project all the vilest wickedness in our own rotten hearts.

12. Humour (1927)

By the early 1920s Freud had devised a radical new tripartite picture of the psyche as consisting of the ego, id and superego, and had posited the existence in the psyche of a powerful death drive. He had done this in order to explain the compulsion to repeat which he saw enacted in situations as varied as shell-shocked soldiers obsessively repeating their dreams of war and a young child’s game of repeatedly throwing a toy away and reclaiming it.

Freud was in a position to apply his new structure and psychology to various literary and psychological phenomena.

Different from jokes or wit, ‘humour’ is what we call irony and is endemic among the British. When the condemned man is walking towards the gallows and he looks up at the sunshine and remarks, ‘Well, the week’s certainly getting off to a pleasant start’ it is his superego making light of the dire situation his ego finds itself in.

Like neuroses or drugs, humour is a way of dealing with the harsh reality we find ourselves in. It is like our parents reassuring us how silly and inconsequential is the big sports game we’ve just lost is, so it doesn’t matter anyway.

As you might expect if you’ve read this far and have been noticing the key themes which emerge in Freud, it turns out that humour, like tragedy, like so much else in Freud, is an act of rebellion:

Humour is not resigned; it is rebellious.

Once again the image of rebellion, whether it’s in art, or vis-a-vis the authorities, or against the smothering restrictions of religion, or, most fundamentally, against the dictates of fate and death themselves, God-less Man’s fundamental posture is one of rebellion and revolt. This feels to me close if not identical to the position of the secular humanist, Camus.

In this brief, good-humoured essay the superego appears in a good light for once, as an enlightening and ennobling faculty, instead of the punitive father-imago which he elsewhere claims underlies secular guilt and depression.

13. Dostoyevsky and parricide (1928)

Which is how he appears here. Burdened with an unnaturally powerful, bisexual ambivalence towards his sadistic father, Dostoyevsky never recovered from the crushing sense of guilt when his unconscious hatred and death-wishes against his father were fulfilled when his father was murdered in a street when Fyodor was 18.

Dostoyevsky’s fanatical gambling and spiritual masochism were aspects of his need to punish himself for his suppressed parricidal death-wishes…which came true!

Freud claims that another aspect of Dostoyevsky’s self-punishment were his epileptic attacks. When he managed to get sent to a prison-camp in Siberia i.e. was sufficiently punished by the outside world, his attacks stopped. He had managed to make the father-substitute, the Czar, punish him in reality, and therefore the attacks from inside his own mind, the psychosomatic epilepsy, could cease.

In amongst these psychological speculations comes Freud’s final word on the individual work of literature which, above all others, was crucial to his philosophy:

It can scarcely be owing to chance that three of the masterpieces of literature of all time – the Oedipus Rex of Sophocles, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov – should all deal with the same subject, parricide. In all three, moreover, the motive for the deed, sexual rivalry for a woman, is laid bare.

He goes on to say that the essence of this master plot has been attenuated as civilisation has done its repressive work to try and conceal it, i.e. what Oedipus does openly and explicitly (murder his father and sleep with his mother) is later carried out by unconsciously envied representatives (by Claudius in Hamlet). But the continuity is certainly suggestive…

And it is in the course of this essay that Freud makes the key remark that the essence of morality is renunciation, the closest he comes to talk about the content of ‘morality’ in the conventional sense, as opposed to a technical approach to its psychological origins and development.

One conclusion among many

If you’ve read through all of this you’ll maybe agree that Freud’s way of seeing things was so distinctive and powerful that, even though much of his claims and arguments may be factually disproved, even if he can be shown to be actively lying about some things, nonetheless, in a strange, uncanny way, it doesn’t stop you beginning to see the world as he does. It’s a kind of psychological infection; or a process of being moved into an entirely new worldview.

Hence the strong feeling he and his followers generated that the psychoanalytic movement he founded wasn’t just a new branch of psychology but an entirely new way of seeing the world, a worldview which gave rise to ‘disciples’ and ‘followers’ in a sense more associated with a religious movement than a simple scientific ‘school’.

Freud was so obsessed with religions because he was founding a new one, and so obsessed with Moses because he identified with him as a fellow founder of a new belief system.

Credit

The history of the translation of Freud’s many works into English forms a complicated subject in its own right. The works in this review were translated into English between 1959 and 1961 as part of The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. All references in this blog post are to the versions collected into Volume 14 of the Pelican Freud Library, ‘Art and Literature’, published in 1985.