This is a stunning exhibition bringing together over 40 paintings by one of the most famous names from the classic period of western art, Peter Paul Rubens (1577 to 1640). It brings together masterpieces from international and private collections, many of which are appearing in the UK for the first time i.e. it represents a unique opportunity for lovers of classic Old Master art. There are some really stunning paintings and a suite of exquisitely crafted chalk drawings on display. It is a feast for the eyes and mind and imagination.

Questioning the Rubenesque

However, it cannot be emphasised too strongly that it is very much a themed exhibition. It really is about Rubens and women.

The stereotypical view of Rubens is as a painter of ample, fleshly, nude women, hence the adjective ‘Rubenesque’, which the Collins dictionary defines as:

‘of, characteristic of, or like the art of Rubens; colourful, sensual, opulent, etc. 2. full and shapely; voluptuous; said of a woman’s figure.’

This exhibition very much sets out to question that stereotype and to show that Rubens painted a much broader range of female characters, in a far greater range of postures, poses and compositions, than the stereotype suggests. Which explains why the poster for the show is very much not of a plump scantily clad woman but of the impeccably buttoned-up Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino (see below).

Strong independent women

Not only that but, in line with contemporary feminist ideology, the exhibition is keen to emphasise that many of these women were far from being passive victims of the male gaze, but in all kinds of ways were, in real life, and in the iconography of the paintings, strong independent women possessed of that key quality of feminist theory, agency.

Thus almost all the 40 or so pictures here are of women, with men playing only peripheral or negligible roles, if they appear at all.

There are paintings of women members of his family, rich influential female patrons, lovely chalk sketches of naked women, key women figures from Christian iconography, and the show builds to a tremendous climax with a final room showing four enormous oil paintings of women figures from classical mythology.

There are some men in some of the paintings, but they are always playing a secondary or negligible role. In the words of the press release:

‘The exhibition will be the first to challenge the popular assumption that Rubens painted only one type of woman, providing instead a more nuanced view of the artist who painted more portraits of his wives and children than almost any other, even Rembrandt. The exhibition reveals the varied and important place occupied by women, both real and imagined, in his world.’

Rubens’ changing style

In a more specialist, art history kind of way:

‘A further theme follows the evolution of the female nude in Rubens’s art. It demonstrates how Rubens’s early nudes were quite different in style from those he became famous for, tracing how he arrived at his preferred form through an engagement with sculpture, careful study of antique models and observation from life.’

Room 1. Introduction

Room one contains eight wonderful oil paintings. One is an early self portrait to introduce the man himself, and then, in line with the exhibition theme, seven portraits of women. First, some historical background:

‘Early in his career Rubens realised that his extraordinary ability to paint portraits could open doors. In May 1600, aged 22, he left Antwerp for Italy, where he stayed until 1608, employed by Vincenzo I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua. This position afforded him opportunities to travel to Spain, Venice, Florence, Rome and to Genoa, where his qualities as a portraitist became fully apparent. Rubens’s dazzling and innovative portraits of noblewomen revolutionised the genre and cemented his relationships with wealthy and powerful patrons.’

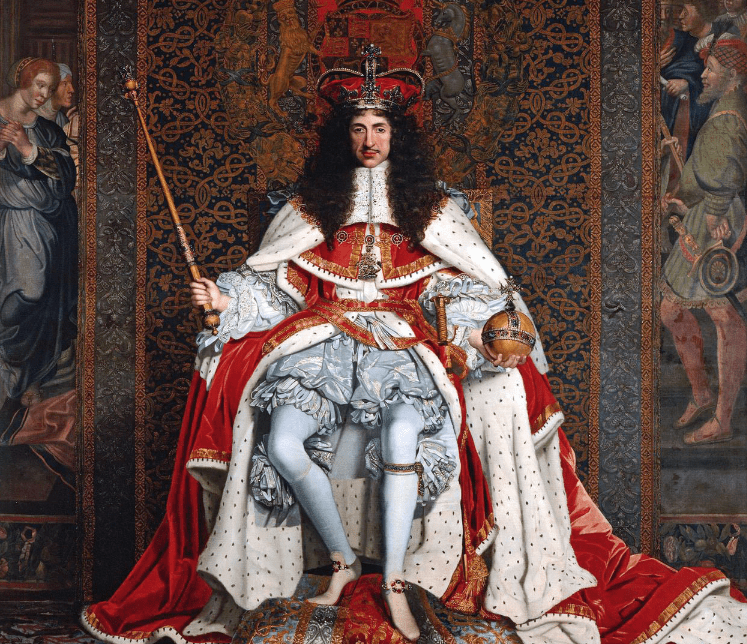

The first room is dominated by an enormous, sumptuous and commanding full-length portrait of the Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino. No reproduction can convey the scintillating, dazzling richness of the oil paint which makes up this awesome, luxury portrait. It is deliberately placed to dominate the first room and announce Rubens’s supreme skill as a painter of power, money and women.

Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino by Peter Paul Rubens (1606) National Trust Collections, Kingston Lacy (The Bankes Collection)

Once you’ve gotten over the visual shock of this huge masterpiece, you can move on to process the six other paintings of women. There’s a further portrait of a powerful woman, Isabel Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain, though depicted in the outfit of a nun, a member of the Order of Poor Clares, reminding us that this was the period of heightened Catholic religiosity referred to as the Counter Reformation.

There’s a series of portraits of ‘unknown women’, resplendent in 17th century dresses, whose luxury fabrics are depicted with loving precision, obviously well-off though not aristocrats.

But maybe the most affecting paintings is the set of ‘intimate’ portraits depicting Rubens’ family, namely his first wife Isabella Brant (1591 to 1626) and eldest daughter, Clara Serena (1611 to 1623), both of whom died relatively young, his daughter at just 12.

Room 2. Figuring Faith

The second room is a long corridor shape and contains paintings and drawings of a religious nature. Working for the Catholic rulers of Antwerp, Rubens was commissioned to create works designed to promote the Counter-Reformation, the Europe-wide movement to revive and reinvigorate Catholic faith, theology, institutions, and project the power of the Catholic monarchs who defended it.

However, in line with the exhibition’s theme of women, the 20 or so works on display here are for the most part not huge, grand, overpowering and religiose images; most of them are relatively modest in scale but what they do have in common is the curators’ wish to foreground Rubens’s treatment of women in the Christian stories.

The Virgin in Adoration before the Christ Child by Peter Paul Rubens (1616 to 1619) KBC Bank, Antwerp, Museum Snyders & Rockox House

It is quite drily funny how, no matter what the subject depicted, the curators insist that the female figures in them are the real stars, the real centres of attention, exercising agency and power in the way every 21st century feminist would approve of.

There’s a wall-sized digital print of an adoration of the Virgin, printed out and plastered on the wall, in which the Virgin is quite obviously receiving her dues from an array of grovelling men.

In a depiction of the Flight into Egypt, it is Mary who taking the ‘heroic’ role of protecting the baby Jesus.

‘Despite the sense of foreboding, and the shadowy rider visible on the horizon, Mary radiates calm.’

There’s an Ascension of Mary which features lots of men in 17th century clerical dress (actually the apostles) but all they can do is stare upwards in amazement at the Virgin taking off into the sky.

There’s two long narrow portrayals of women accompanied by skinny clerics and these turn out to be portraits of two women saints, Walburga and Catherine of Alexandria, strong independent saints.

There’s a study of Saint Barbara fleeing from her father, who has his sword drawn ready to kill her. Typical toxic patriarchy.

By now seeing everything through the eyes of the curators what we notice in a depiction of the ‘The Lamentation’ is that:

‘it is the women who model how we are to respond to this heart-breaking sight. Gazing at Christ, Mary Magdalen pulls at her hair in distress. The Virgin cradles Christ’s body and tenderly closes his eyes. At his feet are The Three Maries (Holy Women from the Bible).’

And at the centre of all this fuss, a dead white man, the best kind.

Denying the Rubenesque

The curators are at pains to emphasise that Rubens’ women are no more voluptuous than those of his predecessors. They are simply more life-like, their skin more convincingly elastic and believably warm. Rubens’ nudes aren’t plumper or more fleshly, they insist, just better painted.

It’s an interesting claim, and I suppose you couldn’t assess it for yourself without reviewing hundreds more works by Rubens and as many by his contemporaries. But the evidence of your eyes tends to suggest that the most striking of Rubens’ women, the climax of his development as displayed in the stunning final room, are chubby, well covered, however you want to express it. See room 4, below.

Room 3. Stone Made Flesh

‘The female nude was a subject of fascination and constant evolution within Rubens’s art. In Italy, Rubens intensively studied ancient sculptures, memorising their forms and postures. He also drew on the Renaissance artist Michelangelo who was similarly informed by ancient art. Recording observations in his notebook, Rubens devised a new type of vigorous, monumental, female nude.’

This room is the most scholarly of the three, an exploration of how Rubens’ modelling of the female figure evolved, especially after a visit to Rome early in his career. This includes a series of studies, finished paintings, a classical marble sculpture, a silverware design, sketches of classical statues, and one large finished oil painting, of Adam and Eve, to demonstrate his early handling of the female nude – all demonstrating his changing approach.

‘Rubens’s nudes became increasingly dynamic and lifelike throughout the 1620s and 1630s.’

All of these works are relatively small and require quite a bit more study and historical knowledge than the bigger, more attractive, finished oil paintings, certainly for an amateur like me.

Alongside these scholarly specimens are eight or so lovely chalk studies of female nudes. I love chalk or charcoal sketches of nudes, male or female. After all these years I still find something magical in the way the human form and shape, the lifeliness of a human body, its warmth and shape, the beauty and pathos of the bare forked animal, can be conveyed by lines of chalk on flat paper when crafted by a master.

All of them were, obviously, really good, but one in particular stood out for me and, despite the blare of the bigger, finished paintings, might have been my favourite thing in the show. After I’ve finished walking slowly through an exhibition, weighed down by the duty of reading the wall captions, I always turn around and walk back, liberated from facts and figures and free to like whatever takes my fancy.

I often play a game where I ask myself, if I can choose just one work from each room, which would it be? This is the one work I’d want to own from the whole exhibition. Scholars think it might be a study for Mary Magdelene, maybe leaning down to wash the feet of Jesus.

What grabbed me is the immense skill of the shading and cross-hatching, the use of black and white chalk, leaving most of the surface untouched and so parchment colour standing in for fleshtone, and how this technique, this skill, can make a person of flesh and blood appear in front of you. The depiction of her lower back, the curve of her bottom, the shading of the thighs and the shadow where her calves are tucking up under her thighs, the creases in the sole of her foot, the five little pinkies. The delicacy, the skill and the exactitude never cease to pluck my heart, make me gasp.

Room 4. Goddesses of Peace and Plenty

In line with their feminist slant the curators emphasise that:

‘The women Rubens depicts are not simply passive figures to be observed but active agents of their own destiny. Nowhere is this clearer than in the dramatic mythological narratives that he loved to paint. Inspired by the Renaissance paintings of Titian and the ancient stories of Ovid and Virgil, in these scenes the goddesses Venus, Juno and Diana are presented as strong and intelligent. It is no coincidence that Rubens’s depictions of powerful, peace-making women were created at a time when his homeland was ravaged by the Eighty Years’ War (1568 to 1648).’

Hence it is that the fourth and final room contains four huge and awe-inspiring paintings with mythological themes and reputedly depicting these active agents of their own destiny, namely:

- Venus, Mars and Cupid (c. 1614) from Dulwich Picture Gallery’s own collection

- Diana Returning from the Hunt (1615) from Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- The Birth of the Milky Way (1636 to 1638) from the Museo del Prado, Madrid, on display in the UK for the first time

- Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia (1625 to 1628) Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

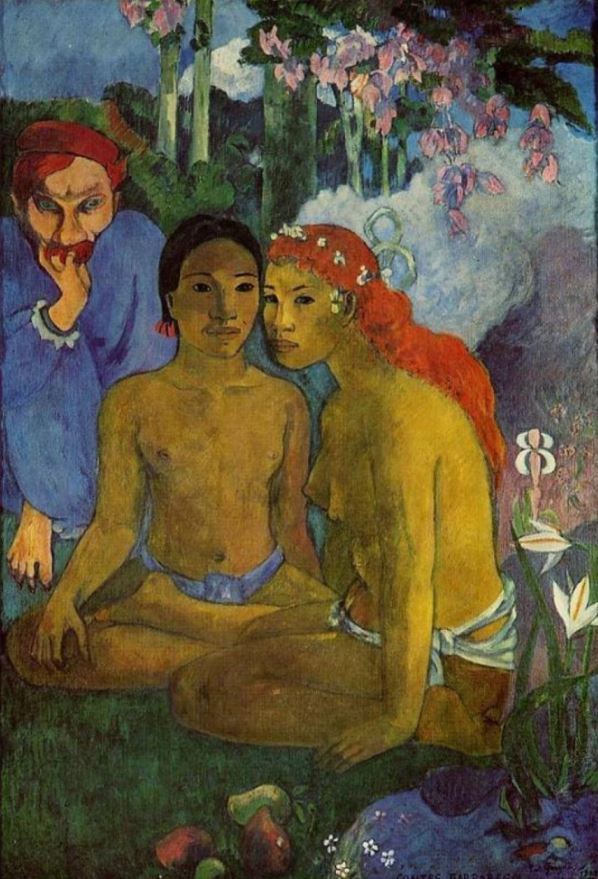

The thing is that, although the curators try their best to claim that these women are not subject to the male gaze, but are strong independent women overflowing with agency, that’s not really how they actually look.

In my opinion this one, ‘Three Nymphs with a Cornucopia’ can be taken as a test case. It depicts the horn of plenty overflowing with the good things of life, namely a grocer’s shop full of ripe plump juicy fruit, so ripe and juicy that it has attracted the attention of scavenging parrots and a cheeky monkey, to add drama and narrative to a classical allegorical scene.

Is it just me or are the two naked women depicted as extensions of this vision of youthful fertile juicy fruitfulness?

I think they are. Far from asserting anyone’s agency, I’d have thought this picture epitomises the reverse: surely these women are totally objectified, depicted in all their youthful sexiness as direct extensions of the world of fruit and fecundity.

This is one of eight paintings Rubens took to Spain as a gift from his patron, the Archduchess Isabel Clara Eugenia, to King Philip IV, to butter him up. Made by a man to flatter a king, far from being a rebuttal it strikes me as being a kind of triumph of the male gaze – sexy topless fruitful babes designed to decorate on the walls of the most powerful man in Europe.

More interesting to me, more persuasive and touching, is the information that Juno, in this huge representation of ‘The Birth of the Milky Way’ resembles Helena Fourment, Rubens’s second wife.

According to the curators, it is thought that his happy second marriage to Helene inspired his increasingly sensuous presentation of women during the 1630s. That seems to me a plausible and happy explanation of the plump sensuality of the nudes he painted in his final decade, just as Rembrandt’s love for his wife shine through his later paintings. I’m not sure anybody portrayed in a painting, male or female, has any ‘agency’. In my opinion they’re all trapped by composition, design, treatment, by the artist’s aims and whims, and all subject to the human gaze of us, centuries later, completely cut off from the value systems in which these works were created.

But paintings very much can convey tenderness and love. And that’s what I found in this small room full of magnificent works of art. The milk of human kindness. Motherly love. The pure, naked, redemptive love we all wish, deep down, we could recapture.

The Birth of the Milky Way by Peter Paul Rubens (1636 to 1638) © Photographic Archive, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Happily ever after

In fact this final wall caption made me realise that mention of Rubens’ second wife had been seeded throughout the show, starting with early mention of how, after the early death of his first wife, in 1630 Rubens married his second and much younger wife, Helena Fourment (1614 to 1673).

‘Their blissful marital state in the final decade of his life, during which time they had five children, provided a wellspring of love and an increased interest in sensual mythological themes.’

In a world afflicted with terrible pain and suffering it cheered me up to learn that this great artist was blessed with a long, happy, rewarding marriage. Good for him! And these images, painted late in his life, at the peak of his experience of art and life, however others may wish to interpret them, struck me as wonderfully accepting celebrations of beauty, humanity and love.

Rubens among his peers

I was struck by a quote from co-curator Dr Ben van Beneden which gives a pithy summary of three of Western Art’s Golden Greats:

‘If Raphael endowed his female figures with grace, and Titian with beauty, Rubens gave them veracity, energy and soul.’

Strong independent parrots

I noticed that one of the most powerful paintings in the final room, the Cornucopia, featured some beautifully vivid parrots pecking away at the fruit flowing from the horn, and this reminded me that the awesome painting of the Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino in the first room also features a parrot perched on her grand chair and bending down, twisting its neck in that inquisitive parrot way.

It occurred to me that maybe Dulwich’s next exhibition should be about ‘Parrots in Painting’. It could bring together depictions of a variety of strong, independent parrots who resist the human gaze to insist on their psittacine agency.

The video

Related links

- Rubens and Women continues at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 28 January 2024

- National Gallery Rubens biography

Related reviews

- Rubens and his Legacy @ The Royal Academy (January 2015)

- More art reviews