This the largest exhibition devoted to the paintings of Dutch master Frans Hals to be held in the UK for more than thirty years and it is a joy from start to finish.

Wall label:

This painting of a carefree lute player in a jester’s costume is one of Hals’s earliest and most successful half-length genre paintings. Unusually, Hals depicted him as seen from below, a vantage point he normally reserved for some of his commissioned portraits. The young man’s sideway glance, cheeky smile, tousled hair and lopsided hat convey a moment of suspended animation. Freely applied brushstrokes enhance the painting’s sense of liveliness and spontaneity.

Joie de vivre

Joy is the key word, along with fun, humour, life and laughter. Hals is the painter par excellence of the enjoyment of life. Eschewing all the other genres of painting, Hals concentrated on the art of portraiture. His master and teacher, Karel van Mander, was a specialist in big works depicting scenes from the Bible and thought portraits were a peripheral, trivial sideline unworthy of a real artist. But his pupil was to prove him wrong and to establish portraiture as the basis of an entire career.

This exhibition demonstrates that portraits themselves come in a variety of types or genres. There are:

- formal portraits showing men of business and of importance in the community

- informal portraits catching people in moments of relaxation

- husband and wife portraits which themselves come in two flavours, either 2 individual works designed to be hung side by side or double portraits with the couple in one composition

- group portraits of, say, the elders of a church, the directors of a company, regents of almshouses or, as here, of local civic guards

- fictional portraits of character types such as the drunk, the buffoon and so on

- tender intimate portraits of family, children and friends

So ‘the portrait’ is a much larger and more varied genre than you would at first think, and this exhibition brings together brilliant examples of all these sub-genres by one of western art’s greatest masters of the form.

Willem van Heythuysen Seated in a Chair by Frans Hals (about 1638) © Private Collection. Courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd, London

Wall label:

The wealthy cloth merchant Willem van Heythuysen commissioned this small picture more than a decade after he posed for one of Hals’s largest portraits (on show in the second room). Hals depicted him nonchalantly tipping back his chair – a highly unconventional pose. His direct gaze and the riding whip in his hand add to the sense of tension. Van Heythuysen hung the portrait in a private room in his Haarlem residence.

Frans Hals (1582 to 1666)

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in Flanders but worked for most of his life in Haarlem, a Dutch commercial city overshadowed by Amsterdam.

Not long after the fall of Antwerp to the Spanish in 1585, as part of the 80 Years War, the Hals family moved to Haarlem in the northern Netherlands. In 1610 Hals enrolled in Haarlem’s Guild of St Luke in order to set up shop as a painter. His skill as a portraitist earned him many commissions from wealthy individuals, married couples, families and militia companies.

Hals’s lifetime was marked by plagues, war and religious controversies but none of that is in this exhibition, none of it intrudes on the stream of joyful, characterful portraits, on the life of people, rich people, businessmen, husbands and wives, drunks, city militias, jokers, entertainers and naughty children.

Wall label:

Laughing children offer coins to a cheerful busker, delighting in the dreadful sounds produced by his ‘rommel-pot’ (a pig’s bladder stretched over a jug). Wearing a fool’s foxtail, the man performs at Shrovetide, a time of merry-making before the fasting of Lent. This early genre painting reveals Hals’s extraordinary talent for characterisation and portraying laughter convincingly – especially that of children. The Rommel-Pot Player became one of the artist’s most popular paintings and was frequently copied.

Northern soul

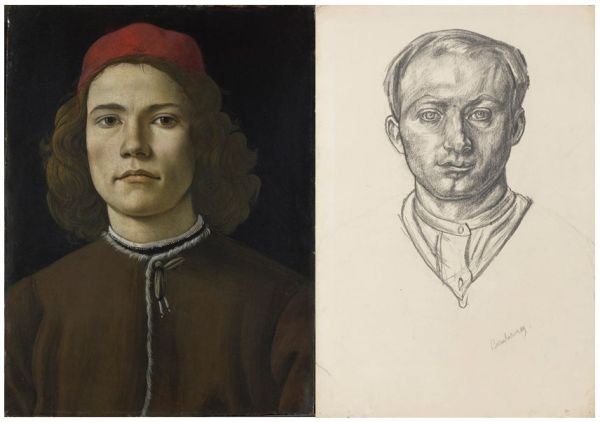

If you’ve read any of my other art reviews you’ll know that I’m biased against the Italian Renaissance, which I find barren, sterile and humourless, and in favour of the Northern Renaissance, which I find full of life, humour and lovely touches.

The early Renaissance rooms at the National Gallery alternate between Italian and northern (German and Flemish) art, the former all hot, harsh, rocky landscapes with humourless Madonnas, the latter lush fields covered in daisies and sweet flowers, smiling ladies with ornate hairdos, quirky characterful northern portraits. I prefer Quentin Matsys to Botticelli.

For me Hals is a continuation of that northern spirit. Instead of sleek beautiful Italians who are all planning how to poison each other or dream of mortifying themselves for Jesus, Hals portrays ugly, jovial, boisterous northerners shouting for more wine, about to tell a particularly rude joke or burst into song. His people are so obviously having fun that it’s impossible not to be carried away by their bonhomie.

Portrait of a Man, possibly Nicolaes Pietersz Duyst van Voorhout by Frans Hals (1636 to 1638) © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Wall label:

The confident pose of this man echoes that of ‘The Laughing Cavalier’, painted more than a decade earlier. It also repeats that picture’s low viewpoint so that the sitter appears to tower over us. Hals rendered The Laughing Cavalier’s decorated outfit fairly precisely, but here he evokes the sheen of the sitter’s satin jacket through wonderfully free handling of the brush.

Quick technique

As far as scholars can tell Hals never made preliminary sketches, he just dived straight in, working alla prima which means applying paint onto previous layers of still-wet paint in a single session, layer over layer, with quick confident brushstrokes.

On the plus side this quick expressive style adds to the sense of vigour and joie de vivre in his sitters. On the downside sometimes it leads to a wonkiness about the features of his people but you’re never quite sure whether that’s down his painterly shortcomings or because many of his sitters were a bit wonky in that ugly north European way.

Young Woman (‘La Bohémienne’) by Frans Hals (about 1632) © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Of this saucy woman the curators write:

The young woman gazes sassily to the side, her smile revealing her teeth. Most 17th-century Dutch viewers would have seen her expression as improper for a woman, indicating lack of refinement or even immorality. Her low-cut blouse suggests that she is a sex worker. This striking painting may have originally been intended for a brothel, where clients could sometimes choose from portraits of the women working there.

Laughter and joviality

When you see a painting or photograph of someone smiling or laughing I think most of us have a tendency to respond positively, maybe to smile along with the image, sometimes unconsciously. When you see a whole series of people laughing, joking, smiling and enjoying life, I think it has a cumulatively positive effect. The more I strolled around this exhibition, reading the wall labels about his friends, families, various bigwigs of Haarlem who Hals depicted in his brisk jovial style, the happier I became. I left the exhibition with a song in my heart.

The curators make the simple point that it’s hard enough to capture the likeness of someone in coloured oil brushed onto a flat canvas, but it’s fiendishly difficult to capture people laughing. All too often the attempt results in people who look like freaks or grotesques which is why so few big name artists ever attempted it. Hals is one of the few artists in all art history to successfully depict people having fun, a major part of human existence which is surprisingly absent from so much art. As the curators put it:

Hals was one of the very few artists throughout the history of Western painting who successfully managed to paint people smiling and laughing; a challenge shunned by most painters because it was so difficult.

His most famous work, ‘The Laughing Cavalier’, is a classic example of this ability although, a moment’s study makes you realise the man is not in fact laughing at all, instead has the ghost of a knowing debonaire smile on his lips, the old dog.

Wall label:

The identity of the smiling (rather than laughing) man depicted in what is arguably Hals’s most famous portrait is not known to us. Its curious title was coined in 19th century England. His luxuriously decorated clothes suggest he was probably a bachelor. Married men tended to dress more soberly. With the man’s hand-on-hip pose, Hals generates a palpable sense of depth.

1. Early works

Between 1601 and 1603 Hals was apprenticed to Karel van Mander, the artist, biographer and art theorist. In 1610, Hals became a member of the painters’ guild of Haarlem and quickly became the most sought after portrait painter in the city. None of Hals’s early works survive. Instead he bursts on the scene aged 28 with a fully finished and marvellous style. Straightaway he is not just portraying people but giving you a vivid sense of their living presence, as in early paintings such as ‘Portrait of Catharina Hooft with her nurse’, about 1620.

Portrait of Catharina Hooft with her Nurse by Frans Hals (1619 to 1620) Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Photo: Jörg P. Anders

2. Portraiture into art

In Hals’s time, portraits had a dynastic function. They preserved the sitter’s place within the family line for posterity. Portraits also expressed status and wealth, often derived through the Dutch Republic’s colonial empire. This room explores how Hals’s fresh, energetic approach allowed him to transform portraiture from a merely functional genre into an expressive, imaginative art form. This was aided by his extraordinarily free, confident brushwork. Most of the paintings are of individual sitters but it also contains two big group portraits of militias.

I find their studied theatrical poses funny e.g. the guy on the right holding out his hand as if to burst into song. It takes a moment to notice that the third sitting from the right is turning his wineglass upside down, ‘More wine, waiter!’ while to his right and the other side of the table a fellow is mashing a lemon in his right hand, squeezing the juice onto a plate of fresh oysters. These are meant to be the respectable members of a responsibly civic guard and yet it looks like a frat party. And the faces! How distinctive and characterful each one is. The curators write:

In Holland, wealthy male citizens often served as officers in their city’s voluntary guards. Earlier group portraits of such militias tended to be formal and static. Hals infused the genre with life, capturing his sitters’ characters and relationships. Hals’s militia group portraits proved popular – he painted six between 1616 and 1639.

3. Invented characters

Portrait commissions for wealthy sitters required a certain decorum. In his scenes featuring ordinary people of the 1620s and 1630s Hals allowed himself more freedom. In many of these works his brushwork becomes even more rough and vigorous.

Hals depicted social ‘types’ with individualised traits, blending elements of portraiture, expressive head studies and ‘genre’ subjects from everyday life. The genre pictures show how Hals engaged with subjects that were popular in Rederijkerskamers (Chambers of Rhetoric), dramatic societies whose performances and poetry featured outlandish characters and imagery.

His characters include merry musicians, laughing fools and rowdy drinkers. He based these on real people, possibly even his own children, as well as on stock characters from satirical plays. Hals himself was a member of a chamber of rhetoric that staged such performances.

The Merry Lute Player by Frans Hals (1624 to 1628) Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London Corporation © Harold Samuel Collection, Mansion House, City of London

Wall label:

Musicians seen up close were already popular subjects when Hals painted this lute player. But he made the motif his own through more plausibly animated characterisations. This merry youth has put down his lute to raise his glass in a spirited toast. Hals has expertly captured the way light reflects on different surf aces, including the glass, the wooden lute and the boy’s sleeves.

Loose brushwork

The exhibition refers continually to Hals’s loose expressive brushwork and this is very evident in every painting. But it’s difficult to judge how this compares with his contemporaries’ practice until you come to a massive painting in this room. This is ‘Young Woman with a Display of Fruit and Vegetables’ and what’s interesting is that Hals only painted the human figure, everything else was done by noted still life painter Claes van Heussen.

Young Woman with a Display of Fruit and Vegetables by Frans Hals and Claes van Heussen (1630) © Courtesy the owner. Photo: The National Gallery, London

The trouble with online reproductions like this is that you can’t make out what is immediately obvious when you see this huge picture (2 metres wide by 1.5 metres high) in the flesh, which is the complete difference in technique between the woman and the fruits. Her face, her clothes, her hands are all done with free vigorous loose brushstrokes and these are in striking contrast with all the fruit, the vegetables, the barrels and baskets and so on, which are painted with microscopic pedantic precision, striving as much as possible for photographic accuracy.

This one painting makes abundantly clear the difference in technique between Hals and other contemporary artists.

4. Family ties

Hals’s sensitivity to personality and presence made him a brilliant observer of relationships. Only one double portrait by Hals survives. This relaxed and intimate work probably represents Isaac Abrahamsz Massa and his wife Beatrix van der Laen. Hals and Massa were friends and Massa is represented in two other portraits on show here.

Portrait of a couple, probably Isaac Abrahamsz Massa and Beatrix van der Laen by Frans Hals (about 1622) © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Wall label:

Few artists can represent nonchalance as well as Hals. The laid-back poses of this couple suggest they are completely at ease with each other. Hals brilliantly captured the casual way the woman rests her hand on her husband’s arm, smiling at us disarmingly.

A large part of his oeuvre consists of pendant – or paired – portraits of couples. Many have been separated over time but pendants are best understood and enjoyed as a single work of art. The exhibition reunites two sets of pendant portraits which have not been seen together in living memory (i.e. Fran ois Wouters and his second wife, Susanna Baillij; and pendant portraits of Tieleman Roosterman and Catharina Brugman).

Occasionally Hals painted an entire family. As with the group portraits of militia guards in the second room, Hals managed complex composition with an air of deceptive ease. The care taken to arrange the sitters is disguised by an overall impression of brisk brushwork and relaxed expressions.

Family Group in a Landscape by Frans Hals (1645 to 1648) © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Wall label:

A symphony of zigzagging brushstrokes, this portrait of an unidentified family centres on the parents. Their eyes are locked in a tender gaze, their joined hands symbolising loyalty and devotion. The daughter looks on while the son and the Black boy look directly at the viewer. The latter’s role in the family is unclear. Forced servitude was illegal on Dutch soil, but he may have been brought to the country as a result of the Dutch Republic’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. European artists in this period often depicted Black people with generic facial features, but here Hals presents the young man’s distinct personality, portraying him with dignity and humanity.

5. Up close

This small room displays half a dozen miniature masterpieces. Best known for his large works on canvas, Hals also painted on a much smaller scale throughout his career. He preferred to paint these smaller works on a smooth surface, usually a wooden panel. Using smaller brushes, Hals employed the same free and expressive technique as in his larger works.

These small portraits make for a more intimate viewing experience. Some will have been intended for the private quarters of a sitter’s residence, to be seen only by family and close friends. Others – mainly of scholars and clergymen – were copied to scale by Haarlem’s most prominent printmakers. The resulting engravings would be used to illustrate books or to circulate the sitter’s likeness. The two standout pieces in this room, for me, were the pendant pair of children making music. These really display loose brushwork to create a terrific sense of immediacy.

Wall label:

These jewel-like pendants celebrate the delights of music. The girl looks down, reading from her song book and tapping her hand to the beat, whereas the boy looks up while playing the violin. These may be the ‘two square portraits of the children of Hals’ mentioned in an inventory of 1644. A Haarlem resident who knew Hals’s children recalled that they were fervent musicians.

6. Late work

In his late work Hals’s painting technique enters its bravest phase. He was around 80 years old when he painted some of the works in this room. At that age the human eye rarely sees as clearly as it once did, but we should not attribute Hals’s late style to diminishing eyesight. His tendency towards an ever-bolder application of paint was a deliberate artistic choice.

The later 17th century saw a general trend towards a smooth style in Dutch painting, think Vermeer. But Hals resolved to pursue his own methods. And as this room attests, there were patrons who preferred his dynamic brushwork and powerful characterisation over what was fashionable.

Like Titian before him, and Rembrandt around the same time, Hals must have decided that a bold – even rough – painting style was a fitting culmination of his lifelong practice.

Here you can really see his brushwork become free and open. Some details made me think of the deliberately rough brushwork of Cézanne or the Impressionists from 200 years later, and the curators tell us that Hals, whose reputation had sunk low, was revived and praised by Impressionist painters, especially Manet.

Probably the single work where you see it most is the Portrait of Jasper Schade. If you scan back through the pictures I’ve included you can see the extravagant attention Hals paid to the details of fabric in his portraits of the lute player, Willem van Heythuysen, Nicolaes Pietersz Duyst van Voorhout, the laughing cavalier or the extraordinary detailed depiction of the gold pattern on the dress of the baby held by Catharina Hooft. Compare the fabrics in all those paintings with the treatment of the jacket worn by Jasper Schade – it really is just a blizzard of white and grey zigzags, completely quick and cursory compared to all those earlier works.

Wall label:

This portrait suggests that Jasper Schade was extremely concerned with looking fashionable. We know from contemporary sources that he had a reputation for spending excessive amounts on his clothes. Throughout his spectacular taffeta jacket, but especially in the sleeve, we can delight in Hals’s brush dancing over the surface of the picture. Tracing each rapid stroke with our eyes probably takes about as long as it took Hals to paint them.

Less obviously rough and ready, my favourite work in the final room is this portrait of a stern, sturdy north European burgher who reminds me of Oliver Cromwell. The loose brushstrokes the curators are talking about are less obvious here, though visible if you peer in close to examine his huge white cuff or the strips of fabric hanging from his belt. Unlike the theme of joking, bantering, laughing joie de vivre which I’ve emphasised to far, it was this guy’s brooding intense stare which stuck with me as I left this wonderful life-enhancing exhibition.

Dutch trio

Hals’s life almost exactly matched what is now called the Dutch Golden Age:

The Dutch Golden Age was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the era from 1588 to 1672, in which Dutch trade, science, and art and the Dutch military were among the most acclaimed in the world. (Google Arts)

He is generally considered one of the trio of great Dutch artists, alongside his younger contemporaries Rembrandt (1606 to 1669) and Vermeer (1632 to 1675).

I’ve read comments sagely pointing out that he’s probably the least of this trio: Rembrandt beats him for his extraordinary handling of chiaroscuro which gestures towards a deeper humanity and a more mysterious spirituality than Hals ever reaches; and Vermeer’s silent interiors take us to a completely alternative universe of stillness and exquisite perceptions.

But still, there is also room in art for lolz and bantz, for the rumbustious enjoyment of life, for squeezing lemon juice onto the oysters and shouting for another bottle of wine. And Hals is the poet par excellence of that smiling, joking, jostling love of life.

Related link

- Frans Hals continues at the National Gallery until 21 January 2024