The most striking characteristic of Symbolist artists is their withdrawal into the realm of the imagination. It is the solitude of the dreamer, of one who, marooned on a desert island, tells stories to himself. It is the solipsistic solitude of one who is sure of nothing outside himself.

(Symbolism, page 35)

This is an enormous coffee-table book, some 31.5 cm tall and 25 cm wide. The hardback version I borrowed from the library would break your toes if you dropped it.

Its 227 pages of text contain a cornucopia of richly-coloured reproductions of symbolist paintings, famous and obscure, from right across the continent, with separate chapters focusing on France, Great Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, the Slavic countries, the Mediterranean countries and so on.

The main body of the text is followed by eight pages giving potted biographies of the key symbolist artists, and a handy table of illustrations. All of this textual paraphernalia. as well as the end-covers and the incidental pages. are lavishly decorated with the evocative line drawings of Aubrey Beardsley.

It is a beautiful book to have and hold and flip through and relish.

Symbolism was a literary movement

So what is Symbolism? A big question which has stymied many art historians. Gibson approaches the problem from a number of angles. For a start, Symbolism (rather like Surrealism) was a literary movement before it was an artistic one. The Symbolist manifesto published in 1886 was written by a poet, Jean Moréas, and was built around analysis of the poets of the day, not the artists, versifiers such as Paul Verlaine (1844 to 1896) or Stéphane Mallarmé (1842 to 1898). In his article Moréas suggested that these writers were aiming ‘to clothe The Idea in perceptible form.’ In looking for ways to illustrate this point he mentioned the similar aim in several contemporary artists, most notably Gustave Moreau.

OK, but what idea? Well, there were eventually hundreds of symbolist painters and the problem is that pretty much every one of them had a different ‘idea’.

Symbolism against the modern world

Gibson takes a different tack, not wasting ink trying to define the elusive ideal and instead offers a sociological explanation. What almost all the symbolist artists had in common was a rejection of the scientific rationalism and the industrial pragmatism of the age (the late nineteenth century). The social and industrial trends of the time were represented by a writer like Émile Zola, who embraced the modern age in all its dirt and squalor and poverty and drunkenness, developing an approach he called ‘Naturalism’, minutely detailed and carefully documented fictions about life as it really was in late nineteenth century France, among seamstresses, coalminers, prostitutes and the like.

In a similar spirit the influential philosopher Auguste Comte preached a social philosophy called ‘Positivism’, which thought that humanity could use scientific and technological advances to create a new society – a technocratic and utopian ideal which found its fullest expression in the English-speaking world in the scientific utopias of H.G. Wells.

Symbolists hated all this. They thought it was killing off all the mystery and imagination in life. They turned their backs on factories and trams and went in search of the strange, the obscure, the irrational, the mysterious, the barely articulatable.

Symbolism a legacy of lapsed Catholicism

Gibson makes the profound point that symbolism mainly flourished in a) Catholic countries b) that had been transformed by industrialisation. If you had only one of these two factors, no dice. Thus the strongly Catholic countries of the Mediterranean (Spain or Italy) were unaffected because they hadn’t suffered the upheavals of widespread industrialisation. Britain was mostly unaffected because, although blighted by industrialisation, it was not a Catholic country. Combining the two criteria explains why symbolism flourished in the northern Catholic regions of heavily industrialised France, Germany and Belgium.

Gibson explains how the Industrial Revolution, coming later to these countries than to pioneering Britain, seriously disrupted the age-old beliefs, traditions and customs of Roman Catholicism. In particular, huge numbers of the peasant population left the land and flocked to the cities, to become a new industrial proletariat (or fled Europe altogether, emigrating to the United States). In the second half of the nineteenth century Europe saw social disruption and upheaval on an unprecedented scale.

Urban intellectuals in Catholic countries felt that the age-old sense of community and tradition embodied by continent-wide Catholicism had been ruptured and broken. Many lost their faith in the face of such huge social changes, or as a result of the intellectual impact of Darwinism, or the visible triumph of science and technology. But they regretted what they’d lost.

Take The Great Upheaval by Henry de Groux (1893). Gibson reads this confusingly cluttered painting as representing the disruption of traditional values in a society undergoing rapid change: note the broken crucifix in the centre-right of the composition.

Symbolism, then, represents the mood right across northern Europe of artists and intellectuals for whom traditional Catholicism had died, but who still dreamed of transcendental values, of a realm of mysteries and hints from ‘the beyond’. As Gibson eloquently puts it, Symbolism is:

the negative imprint of a bygone age rich in symbols, and the expression of yearning and grief at the loss of an increasingly idealised past. (p.24)

Hence the widespread movement among intellectuals to set up clubs, new religious ‘orders’, hermetic societies, cabbalistic cults, to turn to spiritualism, clairvoyance, and a wide range of fin-de-siècle voodoo.

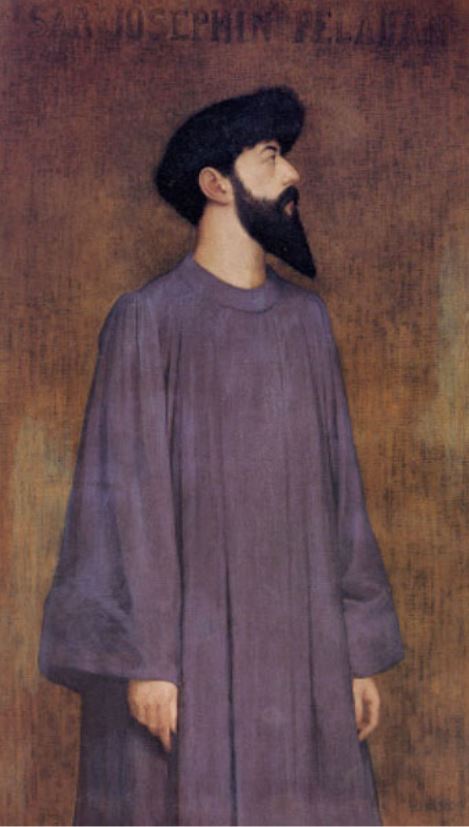

Péladan was one of the founders of the mystical Salon de la Rose+Cross which aimed to support Symbolist art. He changed his name to Sâr (or ‘Magus’) Mérodak.

Mention of voodoo prompts the thought that, up till now I’ve made it sound like harmless replacement for lost religious certainties. I haven’t brought out the widespread sense of anxiety and nightmarish fear which also dominates much of Symbolist art, as in this brilliantly terrifying image by the Belgian painter Léon Spilliaert.

Symbolism and the femme fatale

There’s a lot of threat in Symbolist paintings. In Monet women innocently walk through fields with parasols, in Renoir women are laughing dancing in sunlit gardens. But in Symbolist paintings women tend to be depicted as extremes, either as muses dreaming of another world or as sexually threatening and voracious demons.

The Biblical story of Salome who persuades King Herod to have John the Baptist beheaded, haunts the fin-de-siecle era. Wilde wrote a play about it, Strauss an opera, and there are scores of paintings. In most of them Salome represents the femme fatale, the woman who uses her sexual attraction to lure men into dangerous or fatal situations. Dr Freud of Vienna would have said the real terror lying hidden in these paintings was the male castration complex. Surely the idea was never made more explicit than in this painting by Julius Klinger which shows Salome carrying – not the traditional head of John – but a severed set of testicles and penis drooling blood, along with the blood-red knife with which she has just cut off a man’s penis.

Why this anxiety? Why, above all, did it present itself in sexual form?

Maybe because Symbolist artists were almost all men (there were several successful women Impressionists –Morisot, Cassat – but no female Symbolists that I can see), and that they were dedicated to exploring the irrational aspects of human nature – and not much is more irrational than people’s sex lives, fantasies, desires and anxieties.

And so these men, psyched up to explore the strange, the fantastical, the edgy the socially taboo – ended up projecting onto the blank canvas of ‘woman’ a florid range of their own longings and fears. The ‘irrational’ is not the friend of feminism. Here is ‘Sin’ (1893) by Franz von Stuck.

The smooth white skin and pink nipples and her mild smile of the alluring half-naked woman almost distract you from the enormous snake draped round her neck, resting on her right boob, and ready to bite off your… your what? (‘Paging Dr Freud’ as they used to say in Hollywood screwball comedies.) A very Catholic image since, after all, the basis of Catholicism is the snake tempting Eve who in turn tempted Adam into the Fall. In this image Snake and Woman once again tempt the (male) viewer. Anxious male artist speaking to anxious male viewer.

Symbolism and death

If Symbolist art often portrays Woman (with a capital W) as femme fatale, it just as often betrays anxieties about Death (with a capital D). But Death not as most of us will experience it (hooked up to beeping machines in a soulless hospital ward), Death instead encountered like a seductive figure in a folk tale, often handsome and alluring, often female, even sexy.

Not many images in this genre outdo The Tomb of Arnold Bocklin by Ferdinand Keller for shimmering morbid atmosphere.

Symbolism and decadence

Fin-de-siècle art is often identified with ‘Decadence’, the cult of etiolated aristocrats reclining on velvet divans in an atmosphere heavy with incense and debauchery, as epitomised in the classic novel, Against Nature by J-K Huysmans.

Gibson sheds light on this, too, by saying the Decadence wasn’t fuelled so much by a sense of decline, as by a resolute opposition to the doctrine of Progress, a subtly different idea. This artistically aristocratic sensibility refused to kow-tow to the vulgar jingoism and gimcrack technical advances of the age (telegraphs, telephones, electric lights, early cinema – how ghastly), remaining nostalgic for the imagined superiority of its ancestors in an imaginary, pre-scientific age.

There are always servants in Decadent literature. From a sociological point of view that is one of their most important features. In fact servants feature in the most famous line and much-quoted from the the ‘decadent’ symbolic drama Axël by the French writer Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, where a typically aloof aristocrat drawls:

“As to living, our servants will do that for us.”

The Salon de la Rose+Croix

In 1891 the Symbolist Salon de la Rose+Croix published a manifesto in which they declared that Symbolist artists were forbidden to practice historical, patriotic and military painting, all representations of contemporary life, portrait painting, rural scenes, seascapes, orientalism, ‘all animals either domestic or connected with sport’, flowers or fruit. On the plus side, they welcomed mystic ecstasy, the Catholic ideal, and any work based on legend, myth, allegory or dream (p.56). It’s an accurate enough snapshot of the Symbolist mentality.

- The Sphinx (1896) by Fernand Khnopff

- Detail from Apollo’s Chariot (1914) by Odilon Redon (In the 1890s Redon took to working solely in pastels, like Edgar Degas at the same period.)

This sensibility locks itself away from the world, cloistered (a Catholic image) in an ivory tower, waking only at night (Symbolism is as fascinated by night, by shades of darkness, as Impressionism is by sunlight and daytime: yin and yang).

Rejecting science, the exoteric (obvious) and everyday banality, Symbolism retreats into esoteric studies of the past, into alchemy, into the artificial recreation of medieval ‘orders’ (the more artificial, the more delicious), into mesmeric incantations about sin and death and damnation (overlooking the rather more mundane positive elements of Catholicism – charity, good works and so on).

The vast range of Symbolism

The great success of this book is in bringing together a really vast range of works from right across Europe to show how this mood, this urge, this wish for another, stranger, irrational world, took so many weird and wonderful forms, in the paintings of hundreds of European artists.

And it also investigates the shifting borders of Symbolism, where the impulse to ‘clothe the Idea’ shaded off into other schools or movements, be it post-Impressionist abstraction, Expressionist Angst, Art Nouveau decorativeness, or just into something weird, unique and one-off.

The more I read on and the more examples I saw, the more I began to wonder in particular about the border between Symbolism and ‘the Fantastic’. Despite Gibson’s inclusivity, some of the paintings reproduced here look more like illustrations for fantasy novels than grand gestures towards a solemn mystery world. It’s a tricky business, trying to navigate through such a varied plethora of images.

Here, from the hundreds on offer, are the paintings which stood out for me:

- I lock my door upon myself (1891) by Fernand Khnopff Feels symbolist because its apparent naturalism is very obviously pregnant with meaning: Is she enacting the characteristic gesture of Decadents everywhere, locking herself away from the drab, workaday world?

- Portrait of Georges Rodenbach (1895) by Lucien Levy-Dhurmer A breath-taking combination of immaculate draughtsmanship with the soft shimmering effect achieved by pastels.

- Isabel and the pot of basil (1897) by John White Alexander What magnificent light effects!

- Satan’s Treasures (1895) by Jean Delville Not much mystery about the sexual imagery in this orgy.

- The three fiancées (1893) by Jan Toorop Toorop was half-Javanese hence, apparently, the stick-thin limbs which reference Javanese shadow theatre.

- Money (1899) by Frantisek Kupka Possibly more the illustration to a Grimm’s fairy tale than a work of fine art. Reminding us that the high tide mark of Symbolism was also the classic era of book illustration, by the likes of Arthur Rackham. Can book illustrations be symbolist?

- Sadko (1876) by Ilya Repin Is this symbolist in the sense of pointing towards some deeper meaning – or just plain fantasy painting for its own sake?

Symbolists against nature

Numerous symbolist writers and artists argued that the world of art is radically separate from the so-called ‘real world’. They thought that the Impressionists (who they heartily disliked) were simply striving for a better type of naturalism. Symbolists, on the contrary, wanted next to nothing to do with the yukky real world. As Gibson puts it:

No longer was nature to be studied in the attempt to decipher its divine message. Instead, the artist sought subjects uncanny enough to emancipate imagination from the familiar world and give a voice to neurosis, a form to anxiety, a face, unsettling as it might be to the profoundest dreams. And not the dreams of an individual, but of the community as a whole, the dreams of a culture whose structure was riddled with subterranean fissures. (p.27)

Symbolists found the idea of the total autonomy of the work of art

No following of nature, then, but, in various manifestos, essays, poems and paintings, the Symbolists claimed the total autonomy of art, accountable to no-one but the artist and the imagination of their reader or viewer. Gibson argues that these claims for the complete autonomy of art lie at the root, provide the foundation of, all the later movements of Modernism. Maybe.

Symbolism ended by the Great War

What is certain is that the strange other-worlds of Symbolism came to a grinding halt with the Great War, which tore apart the community of Europe more violently than the Industrial Revolution. The movements which emerged just before and during it – the avant-garde cubists, the violent Futurists, the absurdist Dadaists – all tended to despise wishy-washy spiritualism, all guff about another world. In one way or another they embraced the realities, and excitements, and absurdities, of this one.

Nonetheless, the irrational mood and the imperative to reject the business-like bourgeois world, was revived by the Surrealists (founded in 1924) and it’s easy to identify a continuity of fantastical imagery from the later symbolists through to the Surrealists.

But the Surrealists’ great secret wasn’t other-worldly, it was other-mindly. Their worldview wasn’t underpinned by lapsed Catholic notions of the divine and the demonic. The Surrealists were students of Freud who thought that if they brought the creatures of the unconscious out into the open – via automatic writings and artfully arranged bizarre imagery – they would somehow liberate the world, or at least themselves, from bourgeois constraints.

So much for the theory: but in practice some of the art from the 1920s, and even 1930s, is not that distinguishable from the weirder visions of the 1880s and 1890s.

The conservatism of Symbolism

Reading steadily through the book made me have a thought which Gibson doesn’t articulate, which is that almost all of this art was oddly conservative in technique.

It is overwhelmingly realistic and figurative, in that it portrays human beings (or angels of death or satanic women or whatever), generally painted in a very traditional academic way. There are (as the Rose+Croix wanted) on the whole no landscapes, still lives or history scenes featuring crowds. Instead you get one or two people caught in moments of sombre meaningfulness, but depicted with all the completeness of finish of the most traditional Salon painting.

Hardly any of it is experimental in technique. Not much of it invokes the scattered brush work of a Monet or the unfinished sketchiness of a Degas or the interest in geometric forms of a Cézanne. Nothing in the book is as artistically outrageous as the colour-slashed paintings of the Fauves, of Derain or Vlaminck.

In other words, this art of the strange and the other-worldly comes over as peculiarly conservative. I guess that chimes with the way the belief almost all these artists shared in some kind of otherworld, some meaning or presence deeper than our everyday existence, was profoundly conservative, a nostalgic hearkening back to an imagined era of intellectual and spiritual completeness.

The twentieth century was to blow away both these things – both the belief in some vaporous, misty otherworld, and the traditional 19th century naturalist style which (on the whole) had been used to convey it. Cars and planes, tanks and bombs, were to obliterate the worlds of both tranquil lily ponds and midnight fantasias.