Impressionist artists paint what they see; post-Impressionist artists paint what they feel.

Post-Impressionism

The most important fact about ‘post-Impressionism’ is that the expression was coined in 1910, by an English art critic (Roger Fry), well after the painters it referred to were all dead. It is generally used to describe the principal French painters of the 1880s and 1890s, specifically Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, along with lesser artists of the period – but is an entirely invented, post hoc expression.

This large format book (30 cm tall x 23 cm wide) includes 180 illustrations (80 in dazzling full colour) so that, even without reading the text, just flicking through it is a good introduction to the visual world of the era.

The Impressionist legacy

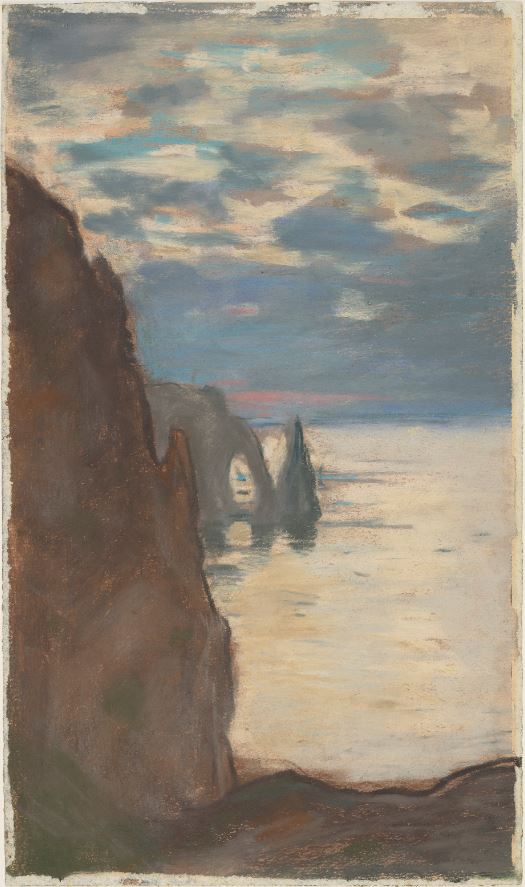

Essentially, the Impressionists in the 1860s and 70s had broken with the constraints of the style of academic painting which was required to gain entry to the annual exhibitions at the official Paris Art Salon – thus also breaking with the traditional career path to establishing a professional livelihood through sales to traditional ‘bourgeois’ patrons.

The Impressionists saw themselves as a group of ‘independents’ or ‘intransigents’ who broke various rules of traditional painting, such as:

- the requirement that a painting depict grand historical or mythological subjects – the Impressionists preferred to depict subjects and scenes from everyday life

- the requirement for each painting to be as realistic as possible a window onto an imagined scene by concealing brushstrokes – whereas the Impressionists foregrounded highly visible dabs and brushstrokes

- the requirement to bring each painting to a peak of completion, with a high finish – whereas the Impressionists often let raw canvas show through, deliberately creating an air of rapid improvisation in pursuit of their stated aim to capture ‘the fleeting moment’

The Impressionists also established the idea of organising group exhibitions independent of the Salon, a new and provocative idea which placed them very firmly outside the official establishment. The history of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, held between 1874 and 1886, is complex and multi-layered.

Meanwhile, their great patron, the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, developed the idea of holding one-artist shows organised in such a way as to show each artist’s evolving style and subject matter, itself a novel idea at the time.

And lastly, the Impressionists garnered from their various writerly supporters a range of manifestos, pamphlets and articles defending them and explaining their artistic principles.

These, then, were the achievements and strategies which the post-Impressionists inherited and took full use of.

The weakness of post-Impressionism as an art history term

Thompson’s book from start to finish shows the problematic nature of the term ‘post-Impressionism’ almost as soon as you try to apply it. Sure, many of the ‘post-Impressionists’ exhibited together at a series of exhibitions in the 1880s and 90s – but they were never a self-conscious group, never had manifestos like the Impressionists.

Far from it, during the 1880s Gauguin, who developed into a ‘leader’ of many of the younger artists, expressed a violent dislike of the so-called ‘neo-Impressionist’ group which developed in the 1890s and which was virulently reciprocated. Yet, despite hating each other, they are both now usually gathered under the one umbrella term, post-Impressionism.

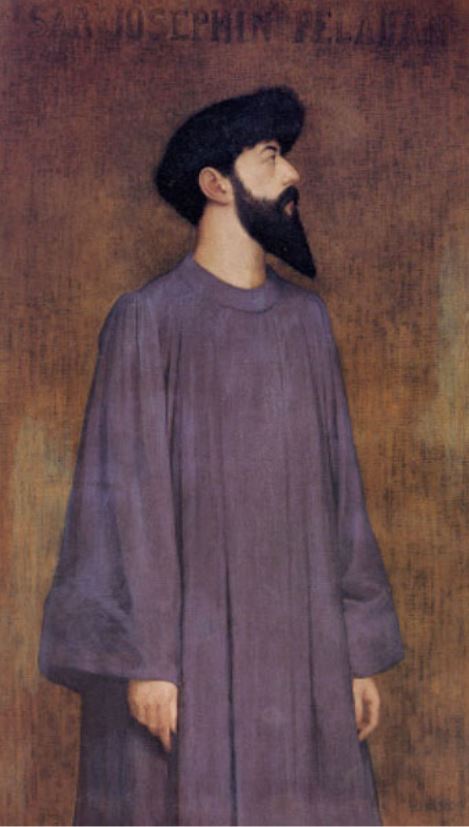

The new young artists of the 1880s and 1890s worked amid a great swirl of artistic movements, which included Symbolism (Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau) and the would-be scientific neo-Impressionism (often identified with Pointillism) of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, as well as the influence of non-French artists such as Ferdinand Holder (Swiss) or James Ensor (Belgian) and, of course, of the Dutchman Vincent van Gogh. All of these came from different traditions and weren’t so in thrall to the essentially French Impressionist legacy.

Again and again consideration of the term post-Impressionism breaks down into the task of tracking the individual careers and visions of distinct artists – with the dominating personalities being Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, but with lesser contemporaries including Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Eduard Vuillard also contributing.

If you can make any generalisations about the ‘post-Impressionists’ it is around their use of very bright, harsh garish colours (compared with the Impressionists’ more muted tones) and their departure from, their flying free from, the constraints of a ‘naturalistic’ ideology of painting ‘reality’.

In summary

Thompson’s book is an excellent and thought-provoking account of the complex of commercial pressures, individual initiatives and shifting allegiances, characters, theories, mutual competition, individual entrepreneurship and changing loyalties which undermine any notion of a clear discernible pattern or movement in the period – but which makes for an absorbing read.

Four key exhibitions

The first half of the book gives a detailed account of a series of key exhibitions, which she uses to bring out:

a) the differences between so many of the artists

b) their changing ideas and allegiances

1. The Eighth Impressionist Exhibition (1886)

Of the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition we learn that only Degas, Pissarro, Guillamin and Berthe Morisot of the original group exhibited, Renoir and Monet having cried off, partly hoping still to exhibit at the Salon. Degas created a lot of ructions by insisting that the show take place during the same weeks as the official Salon’s big annual exhibition – a deliberately provocative gesture – and insisting that a number of his figure-painting friends take part, though they had little real affinity with Impressionism (namely Mary Cassatt, Forain, Zandomeneghi and the completely unrelated Odilon Redon).

It is useful to learn that the pointillists Seurat and Signac, along with the old-timer Pissarro and his son Lucien (who were both experimenting with pointillism), were given a room of their own. This explains why they gave such a strong vibe of being a new and distinct movement and so prompted the critic Félix Fénéon to give them the name ‘Neo-Impressionists’.

As mentioned above, Gauguin had a falling-out with Signac which led the followers of both to crystallise into opposing camps.

2. The Volpini Exhibition (1889) ‘Groupe Impressioniste et Synthétiste’

To mark the centenary of the Great Revolution of 1789, the French government sponsored a huge Universal Exhibition, to be held in buildings erected in the grounds around the newly opened Eiffel Tower.

As part of the Exhibition the Salon/Academie of Beaux-Arts staged a big show designed to tell the story of French painting over the previous century, which included some but not many of the Impressionists, and then only of their early works.

Gauguin organised a rival show at the Cafe Volpini in the nearby Champs de Mars made up of artists he had met painting in Brittany, including Émile Bernard, Émile Schuffenecker, Charles Laval, Léon Fauché and Louis Roy. Later historians credit this show with the launch of a ‘Pont-Aven’ school (named after the French town where Gauguin had developed his style) but Thompson shows how varied in look and style these artists were, which tends to undermine that claim.

Notable were the absentees: Toulouse-Lautrec was considered for the Volpini show but eventually debarred because he’d been exhibiting at a private club, and van Gogh, who desperately wanted to be included, was prevented from doing so by his art dealer brother, Theo, who thought it was a tacky alternative to the official Exhibition.

To the untrained eye the pieces shown here:

- have gone completely beyond the Impressionist concern for the delicate depiction of light and shadow into a completely new world of vibrant colours and stylised forms – The Buckwheat Harvest by Émile Bernard

- and, if they are depicting ‘modern life’, they do so with – instead of dashes and daubs of light – very strong black outlines and sinewy lines, very much in line with Lautrec’s work and the feel of Art Nouveau – Avenue de Clichy, Five O’Clock in the Evening by Louis Anquetin

The word ‘synthétiste’ appeared, applied to Anquetin’s work, and meaning the combination of heavy dark outlines with areas of flat, unshadowed, uninflected colour.

The art critic Fénéon wrote an insightful review of the exhibition in which he singled out Gauguin as having found a new route past Impressionism which was also completely opposite to the pseudo-scientific approach of the pointillists, a style in which Gauguin:

rejects all illusionistic effects, even atmospheric ones, simplifies and exaggerates lines

giving the areas created by the outlines vibrant, often non-naturalistic colouring. Breton Calvary, the Green Christ (1889).

During the late 1880s a young painter named Paul Sérusier, studying at the Academie Julian, had gathered a number of devotees who called themselves the ‘Nabis’ or prophets, and they decided that Gauguin was the vanguard of a new painting and set off to Brittany to meet and copy the Master.

Gauguin was also at the core of an essay written by the painter and critic Maurice Denis – ‘Definition of Neo-Traditionism’ – which claimed that:

- Gauguin was a master of a new style which emphasised that a painting is first and foremost an arrangement of colour on a flat surface

- therefore, it is futile trying to achieve illusionistic naturalism

- and that the neo-traditionists (as he called them), having realised this, were returning to the function of art before the High Renaissance misled it, namely to create an art which is essentially decorative – which doesn’t pretend to be anything other than it is

3. The Fourth Le Barc de Boutteville Exhibition of Impressionists and Symbolists (1893)

This exhibition featured 146 works by 24 artists and displayed a bewildering variety, including as it did Impressionists like Pissarro, neo-Impressionists like Signac, the independent Toulouse-Lautrec, ‘school of Pont-Aven’ followers of Gauguin, and ‘Nabis’ like Bonnard and Vuillard. If it sounds confusing, that’s because it is confusing.

The explanation for it being such a rag-tag of different artists and styles is that it was one of a series put together by the thrusting new art dealer, Le Barc de Boutteville. The main beneficiaries were the ‘Nabis’ who fitted in well with the contemporary literary movement of symbolism. Nabi landscape by Paul Ranson (1890).

Thompson brings out the political differences between the pointillists – generally left-wing anarchists – and the Nabis – from generally well-off background and quickly popular with established symbolist poets and critics.

4. The Cézanne One-Man Show (1895)

Cézanne acquired the reputation of being a difficult curmudgeon. In the early 1880s he abandoned the Paris art world and went back to self-imposed exile in his home town of Aix-en-Provence. When his rich father died in 1886, Cézanne married his long-standing partner, Hortense, moving into his father’s large house and estate. To young artists back in Paris he became a legendary figure, a demanding perfectionist who never exhibited his work.

The 1895 show was the first ever devoted to Cézanne, organised by the up-and-coming gallery owner and dealer, Ambroise Vollard. The 150 works on display highlighted Cézanne’s mature technique of:

- creating a painting by deploying blocks of heavily hatched colour built up with numerous parallel brushstrokes

- his experiments with perspective i.e. incorporating multiple perspectives, messing with the picture plane

- his obsessive reworkings of the same subject (countless still lives of apples and oranges or the view of nearby Mont Sainte-Victoire)

The one-man show marked a major revaluation of Cézanne’s entire career and even prompted some critics to rethink Gauguin’s previously dominant position, demoting him as leader of the post-Impressionists and repositioning him as the heir to a ‘tradition’ of Cézanne, placing the latter now as a kind of source of the new style.

You can certainly see in this Vollard portrait something of the mask-like faces of early Matisse, and the angular browns of Cubism (Picasso was to paint Vollard’s portrait in cubist style just 11 years later), even (maybe) the angularities of Futurism. It all seems to be here in embryonic form.

Thompson’s analysis of these four exhibitions (chosen from many) provides snapshots of the changing tastes of the period, but also underlines the sheer diversity of artists working in the 1880s and 1890s, and even the way ‘traditions’ and allegiances kept shifting and being redefined (she quotes several artists – Bernard, Denis – who started the 1890s revering Gauguin and ended it claiming that Cézanne had always been their master).

Themes and topics

In the second half of the book Thompson looks in more detail at specific themes and ideas of the two decades in question.

From Naturalism to Symbolism

If one overarching trend marks the shifting aesthetic outlooks from 1880 to 1900 it is a move from Naturalism to Symbolism. In 1880 artists and critics alike still spoke about capturing the natural world. Symbolism was launched as a formal movement in 1886 with its emphasis on the mysterious and obscure. By the end of the 1880s and the early 1890s artists and critics were talking about capturing ‘hidden meanings’, ‘subtle harmonies’, ‘penetrating the veils of nature’ to something more meaningful beneath.

Thus although Monet and Cézanne continued in their different ways to investigate the human perception of nature, the way their works were interpreted – by critics and fellow artists – shifted around them, influenced by the rise of an increasing flock of new art movements.

Thompson vividly demonstrates this shift – the evolution in worldviews from Naturalism to Symbolism – by the juxtaposition of Women Gleaning (1889) by Camille Pissarro and Avril (1892) by Maurice Denis just a few years later.

The difference is obviously one of vision, style and technique, but it is also not unconnected with their political differences. Pissarro was a life-long left-winger with a strong feel for working people: his oeuvre from start to finish has a rugged ‘honesty’ of subject and technique. Denis, by contrast, was a committed Catholic mystic who spent his career working out a private system of religious symbols, a personal way of depicting the great ‘mysteries’ of the Catholic religion.

Politically, thematically, stylistically, they epitomise the shifting currents, especially of the 1890s.

‘Synthesis’

Synthesis/synthetism was a common buzzword of the Symbolists. It means the conscious simplification of drawing, of composition and the harmonisation of colour. Included in this general trend were the taste for Japanese art (liked by everyone from the 1870s onwards), the symbolist fashion for ancient art e.g. from Egypt, and for ‘primitive’ European art i.e. the Italian 14th century.

(This growing taste for exotica and the non-European obviously sets the scene for the taste for Oceanic and African art which was to come in in the early years of the 20th century.)

Interestingly, Thompson shows how this same line of interpretation – simplification, strong outline, unmediated colour – can be applied both to Seurat’s highly academic pointillist paintings and, in a different way, to the violently subjective works of Gauguin. On the face of it completely different, they can be interpreted as following the same, very basic, movement in perception.

Portraiture

Cézanne’s portrait of Achille Emperaire (1868) was contemptuously rejected by the judges at the Salon. 20 years later, hung at the back of the collector Père Tanguy’s shop, it was a subject of pilgrimage and inspiration to the new generation – to the likes of Gauguin, van Gogh, Bernard and Denis.

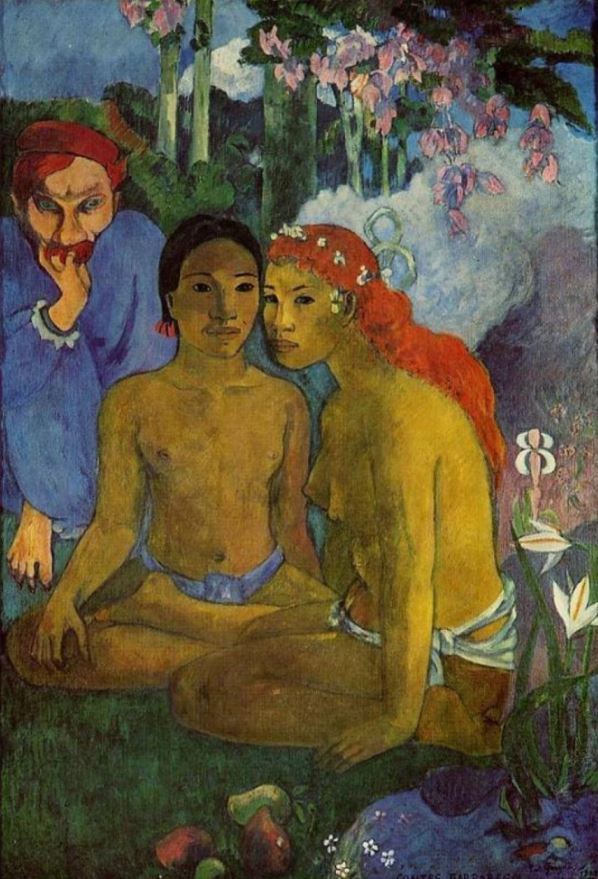

Thompson explores the differing approach to portraits of more marginal figures like Redon, van Rysselberghe and Laval, but the centre of the chapter compares and contrasts Gauguin’s virile ‘synthetic’ self-portraits with van Gogh’s quite stunning self-portraits.

The examples Thompson chooses show both artists as head and shoulders above their peers, with van Gogh achieving a kind of god-like transcendence.

Gay Paree

Thompson makes the interesting point that ‘Gay Paree’ was largely a PR, press and tourist office invention of the last decades of the 19th century, capitalising on the proliferation of bars, circuses and cabarets, epitomised by the Moulin Rouge, opened in 1889, and marketed through the expanding medium of posters and adverts in new, large-format newspapers and magazines.

Yet by the 1890s this had become a darker vision, a night-time vision. Thompson compares the lovely sun-dappled idylls of Renoir, who painted working class revellers at the Moulin de Galette cafe in Montmartre in the 1870s – with the much darker, sometimes elegant-sometimes grotesque visions of the dwarfish aristocrat, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec – At the Moulin Rouge (1892). The 1890s were a darker decade.

Politics

In the last few chapters Thompson brings in an increasing amount of politics. The chapter on Gay Paree had already brought out how life for the average working class Parisian, despite the tourist posters, still involved harsh, long hours at poor pay (and she throws emphasis in particular on the exploitation of women – as laundry women, washerwomen, shop assistants, and the huge army of prostitutes).

This is all set against the increasing political turmoil in Paris, which saw a number of anarchist bombings in the 1880s and 1890s leading up to the assassination of President Carnot in 1894, who was stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist. In the backlash, some art critics were arrested for their left-wing sympathies and left-wing artists (Pissarro and most of the pointillists) kept their heads down.

Later the same year – 1894 – saw the beginning of the long, scandalous Dreyfus Affair, which started with the arrest of a Jewish army captain for supposedly leaking military secrets to the Germans. He was tried and found guilty on very shaky evidence then, after a long campaign to free him, another trial was held, which found him guilty again and sentenced him to hard labour on Devil’s Island.

(Although it’s a fiction book, Robert Harris’s An Officer and a Spy gives the most detailed account of the evidence and the successive trials which I’ve read.)

The affair dragged on for over a decade, driving a great wedge between supporters of the Establishment, of the law and justice system, of la patrie and of Catholicism – and liberal and left-wing politicians and sympathisers, who saw the whole thing as an embarrassing stitch-up, as the symbol of a fossilised reactionary order which needed to be overthrown.

The Affair also brought out a virulent strain of antisemitism among anti-Dreyfusards, who used his supposed guilt to implicate the whole world of cosmopolitan culture, corruption, decadent art, sexual perversion and all the usual suspects for right-wing ire.

And the Affair divided the art world. Degas, in particular, comes off very badly. As a conservative anti-Dreyfusard, he severed ties with all Jews of his acquaintance (including his old Impressionist colleague, Pissarro). Shameful.

The Dreyfus Affair brought into focus a movement on the right, known as le Ralliement, which attempted to bring all the forces of ‘order’ into one unified movement in order to combat the perceived growth of working class and socialist movements.

Suffice to say that the artistic developments of the 1890s took place against a darker, more intense social background than that of the 1880s.

Thompson shows how this shifting political backdrop can be read into the art of the 1890s, with Catholic artists like Denis producing works full of Christian imagery, while the perfectly balanced and idealised visions of the neo-Impressionists (given that most of them were well-known left-wingers) can be interpreted as the depiction of a perfect socialist world of justice and equality.

In this more heavily politicised setting, the apparently carefree caricatures of Toulouse-Lautrec gain a harsher significance, gain force as biting satire against a polarised society. (Certainly, the grotesqueness of some of the faces in some of the examples given here reminded me of the bitter satirical paintings of post-war Weimar Germany, found in Otto Dix and George Grosz.)

Meanwhile, many other artists ‘took refuge in’ or were seeking, more personal and individual kinds of spirituality.

This is the sense in which to understand Thompson’s notion that if there is one overarching movement or direction of travel in the art of the period it is out of Naturalism and into Symbolism.

At its simplest Symbolism can be defined as a search for the idea and the ideal beneath appearances. Appearances alone made up more than enough of a subject for the Impressionists. But the post-Impressionists were searching for something more, some kind of meaning.

In their wildly different ways, this sense of a personal quest – which generated all kinds of personal symbols and imagery – can be used to describe Cézanne (with his obsessive visions of Mont Sainte-Victoire), Gauguin’s odyssey to the South Seas where he found a treasure trove of imagery, Van Gogh’s development of a very personal symbolism (sunflowers, stars) and even use of colours (his favourite colour was yellow, colour of the sun and of life), as well as the journeys of other fin-de-siecle artists such as the deeply symbolic Edvard Munch from Norway – who Thompson brings in towards the end of the book.

Landscape

In the chapter on landscapes Thompson is led (once again) back to the masterpieces by those two very different artists, van Gogh and Gauguin. Deploying the new, politicised frame of reference which she has explained so well, Thompson judges the success or failure of various artists of the day to get back to nature, specifically to live with peasants and express peasant life.

Judged from this point of view, Gauguin comes in for criticism as a poseur, who didn’t really share the peasant superstitions of the people he lived among in Brittany any more than he really assimilated the non-European beliefs of the peoples of Tahiti where he went to live in 1895.

He is contrasted with the more modest lifestyle of Pissarro, who lived in relative poverty among farmers outside Paris more or less as one of them, keeping his own village plot, growing vegetables, keeping chickens.

Or with van Gogh, who had a self-appointed mission to convey, and so somehow redeem, the life of the poor.

Conclusion

This is an excellent introduction to a complicated and potentially confusing period of art history. Not only does it give a good chronological feel for events, but the chapters on themes and topics then explore in some detail the way the various movements, artists, styles and approaches played out across a range of subjects and themes.

Paradoxically, the book is given strength by what Thompson leaves out. She doesn’t mention the Vienna Secession of 1897, doesn’t really explore the Decadence (the deliberately corrupt and elitist art of drugs and sexual perversion which flourished in the boudoirs and private editions of the rich), she mentions Art Nouveau (named after an art gallery founded in 1895) once or twice, but doesn’t explore it in any detail.

Mention of these other movements makes you realise that post-Impressionism, narrowly defined as the reaction of leading French artists of the 1880s and 1890s to the Impressionist legacy, was itself only part of a great swirl and explosion of new styles and looks in the 1890s.

It may be pretty dubious as an art history phrase, but ‘post-Impressionism’ will probably endure, in all its unsatisfactoriness, because it helps mark out the three or four main lines of descent from Impressionism in France – neo-Impressionism, neo-Traditionism, and specifically the work of Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, and Seurat – from the host of other related but distinct movements of the day.

Self-portrait with portrait of Bernard (1888) by Paul Gauguin

Nineteenth century France reviews