This is a lovely exhibition, the first major UK exhibition of the leading French Impressionist Berthe Morisot’s work since 1950, but it’s also much more than that.

It is also a sustained comparison of Morisot’s work with the 18th century artists she knew and loved, which means that about a third of the paintings on display (about 15 out of a total 45 or so) are not by Morisot at all, but by eighteenth century classics, such as Watteau, Fragonard, Boucher and, surprisingly, the Brits Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.

A collaboration

How did this come about? Well, the Musée Marmottan Monet is ‘the world’s leading research centre for the work of Berthe Morisot’ and it turns out that Morisot was very influenced by eighteenth century art – the French eighteenth century work of Fragonard and Watteau and Boucher, but also the English eighteenth century art which she saw on her honeymoon to England in 1875.

And Dulwich Picture Gallery houses a celebrated collection of 18th century painting. So this exhibition is by way of being a collaboration between these two galleries – The Musée Marmottan Monet providing nine key examples of Morisot’s work (along with prime examples from international collections) and these are then juxtaposed with French and English eighteenth century paintings from the Dulwich collection and elsewhere – with the aim of demonstrating Morisot’s debt to the previous century, both in subject matter and aspects of her painting style.

Berthe Morisot potted biography

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot (1841 to 1895) was a French painter and a founding member of Impressionism. In 1864, she exhibited for the first time in the highly esteemed Salon de Paris. Her work was selected for exhibition in six subsequent Salons until, in 1874, she joined the ‘rejected’ Impressionists in the first of their own exhibitions, a show which included Cézanne, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley. Morisot went on to participate prominently in seven of the eight Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886 (she missed one in 1878, having just given birth to her daughter, Julie). In 1894 the art critic Gustave Geffroy as one of ‘les trois grandes dames’ of Impressionism, alongside Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt.

Morisot was well connected. She came from an affluent family who secured her painting lessons, first copying works in the Louvre, and then as a pupil to landscape painter Camille Corot, who taught her to make swift outdoor sketches.

She married Eugène Manet, brother of her friend and colleague Édouard Manet. Her sister, Edma, was also a painter. The Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarmé was a family friend. She was a member of the haut bohemien.

Room one

The exhibition is in four rooms. The first room contains eight paintings, designed partly to give you an introduction to her light and airy style, but almost all of the captions also draw attention to the fact that, even at the time, many critics spotted her closeness in spirit to eighteenth century painting.

What they meant was that something in the lightness and airiness of her style, something in the domestic intimacy of her subjects (almost entirely women), and even in her use of shades of white and silver, related directly back to the mood and tone of French Rococo painting.

‘Woman at her Toilette’ by Berthe Morisot (1875 to 1880). Image courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund

Take ‘Woman at her Toilette’. To quote the curators:

With its silvery palette and fluent brushwork, the painting appears as ephemeral as a mirror reflection. Reviewing it at the Fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1880, art critic Paul Mantz noted: ‘everything floats, nothing is formulated […] there is here a finesse like that found in Fragonard.’

Or:

‘The genius of the eighteenth century, but not its debauchery, lives again in these familiar and select images, which are animated by a kind of airy voluptuousness.’ (Henri Focillon)

Or take the painting at the start of this review, ‘At the Ball’. The woman in evening dress is holding an eighteenth-century fan, opened to display a picture-within-the-picture, a scene of outdoor courtship known as a fête galante, a genre invented by the eighteenth-century artist Watteau. (The fan belonged to Morisot and is included in the exhibition so we can admire its civilised 18th century style.)

Morisot was fond of making this kind of allusion to eighteenth-century visual culture and the connection proved attractive to collectors. The curators tell us that Rococo art had gone into a long period of neglect after the French Revolution but that, in Morisot’s generation, it underwent a revival. Exhibitions reintroduced eighteenth-century French art to the public and the Louvre opened new rooms devoted to the era.

So when Renoir declared her ‘the last elegant and “feminine” artist that we have had since Fragonard’ and Paul Girard, reviewing her summary exhibition in 1896 commented that her work was ‘the eighteenth century modernised’, it showed that she was very much on trend, and it was reflected in her sales. ‘At the Ball’ was bought from the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876 by art collector Georges de Bellio, to complement his existing collection of eighteenth-century art, and many of her works were sold to collectors with similar tastes.

Room two

The second room has the highest proportion of non-Morisot to Morisot, 8 or so works by other artists to her four. This is the room where the curators show a number of eighteenth century works and explore Morisot’s relationship to them. This turns out to be quite complicated, in the sense that she had a multi-levelled relationship with the artists of the preceding century, which evolved over time.

Engaging the classics

In her late teens and early twenties she had undergone supervised training which consisted of copying classic works at the Louvre. Over 20 years later, she returned to the Louvre to engage with the classics, no longer copying them but translating them into her own, loose, rough, late-impressionist style.

In her forties and fifties, Morisot engaged directly with grand mythological paintings in museum collections, translating elements of their compositions into her own Impressionist language. Unlike the copies that formed part of her own early training, these are original interpretations by a confident, mature artist.

Thus the exhibition shows us (a photo of) Apollo revealing his divinity to the shepherdess Issé by the great Rococo painter François Boucher:

And then shows us Morisot’s interpretation or translation or reinvention of the two embracing young women at the bottom left of the painting into her own hazy, light, unfinished style:

‘Apollo revealing his divinity to the shepherdess Issé, after François Boucher’ by Berthe Morisot (1892) © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Now this raises all kinds of questions. On the face of it, I prefer the Boucher, as I consistently preferred all the 18h century originals to Morisot’s ‘interpretations’ when they were laid side by side. There’s more depth, more perspective, more (wonderful) painting technique, more detail and more visual pleasure to be had by the works by Fragonard, Boucher and Watteau on show here. They look and feel like the luxury objects they were intended to be.

And yet, Morisot’s work is doing something different: its looseness, its rough finish, its lack of interest in realistic perspective or twinkly detail are the result of something else. There’s a lot of experimentation going on in the technique, namely the long, blunt, wide brushstrokes which can be seen in the green reeds. (And it’s fascinating to learn that Monet very much liked this feature of Morisot’s later style, and went on to use a similar combination of short and longer sinewy brushstrokes and pastel colouring in his paintings of water lilies.)

But, arguably, there’s also a psychological dimension at play. In the Boucher work, the embracing women are yet more examples of the kind of sumptuous sensuality which floods the painting. In Morisot’s version they’re still naked, and we can see the outlines of their bodies, and yet these bodies are being dissolved into or drowned or clambered over by the powerful green reeds, powerful green reeds which, on the left, swirl and curve, leading the viewer’s eyes into a background which isn’t magically alluring but is more unadorned and bleak. Humanless and troubling.

The female gaze

Something similar can be said of another direct comparison the show gives us. First, look at this characteristically sensual and saucy painting by Fragonard of a woman reclining, all pink nipples and soft porn confection:

‘Young Woman Sleeping’ by François Boucher. Fondation Jacquemart-André – Institut de France, Domaine de Chaalis, Fontaine- Chaalis

Pretty obviously this painting, and this entire genre of painting, was designed to please and titillate its male audience with what T.S. Eliot called the ‘promise of pneumatic bliss’. And here is Morisot’s reinterpretation:

Same subject i.e. head and shoulders of a topless young woman reclining on an ornamental sofa or bed and yet…the Morisot comes from a different world, both artistically and psychologically. On the painterly level, the Bouchard buries the outlines of the subject in a realistic depiction i.e. you see more or less what you would see in real life, maybe a little Photoshopped and improved, but the outlines are soft a gentle.

On the contrary, the Morisot makes a point of emphasising outlines. Note the strong green lines shaping her hair, particularly as it tumbles onto her shoulder, the outline of her right shoulder against the pillow, the outlines of her right boob and forearm and left handing resting on it.

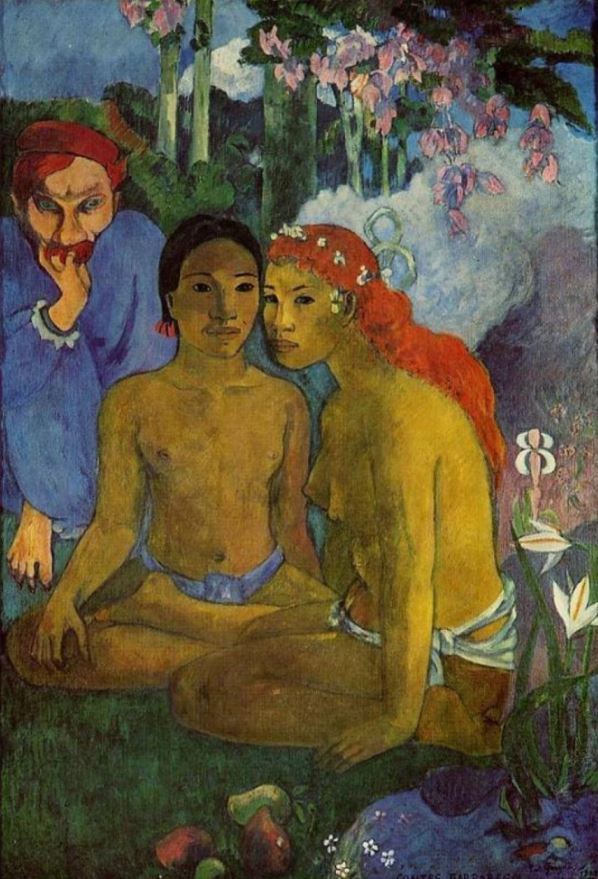

This painting isn’t interested in realism; it is making a statement about the artificiality of painting itself. In this respect, several of her later (this is from 1892) works reminded me of Gauguin, who had long ago ceased bothering about ‘realism’ and become interested in simplifying patterns and designs using heavy outlines, shapes which refer back to objects in the real world but take them a long way towards a kind of primitive abstraction.

Morisot isn’t Gauguin, but I thought some of her later works had moved just as far beyond impressionism, but in her own distinctive way. Another vivid example is ‘Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laertes’ from right at the end of her life (1893 – she died in 1895)

The straight-on face and the black, very loosely painted dress, reminded me of Edvard Munch more than Renoir or the other classic-era impressionists.

And this brings me to the other aspect of the work, which is its psychological impact. The Bouchard woman, a sleek airbrushed imago, has been painted for male viewing pleasure. The Morisot picture for other reasons altogether. As discussed, it is, on one level, an exercise in painterly technique, in exploring the world beyond pure realism. But on a psychological level it is just as complex. This woman doesn’t exist to give any man pleasure. This isn’t painted for the controlling male gaze. She comes across as a real individual, with idiosyncratic hair, colouring, non-male-fantasy boobs; like a painting of a woman who happens not to be wearing a top.

And, as well, there is some kind of power radiating from t, a sense of psychological depth. She reminds me of the heroines of late Victorian fiction, of Hardy or Zola or Henry James, of women whose every transient thought and emotion and response is annotated and analysed in vertiginous detail over three or four hundred pages novels.

There are a lot of paintings of women in the exhibition but, in my opinion, there is quite a big gulf between Morisot’s pretty-pretty, dressed-up Victorian women from the 1870s and 1880s, which are often variation on Renoir’s delightful dancing ladies – and these later depictions, which are something altogether different. They anticipate the much blunter honesty and psychological complexity of much early twentieth century portraiture.

Working in pastel

Room three also contains a useful contrast in the medium of pastel. From the 18th century we have a stunningly beautiful portrait of an unknown man by Jean-Baptiste Perronneau. This is the kind of work that has to be seen in the flesh to be appreciated. A reproduction like this flattens and smooths it out. In the flesh you can see the amazing amount of work that’s gone into the pastelwork, for example the way repeated layerings of broad blue crayon create a rich sensual impression like you could reach out and touch it, whereas, the wall label tells us, the intricate detail of his neckerchief was achieved with a fine-nibbed pen. It looks pretty good in this reproduction, but it’s a wonder to stand in front of.

Portrait of a Man, Thought to be Louis Journu, Known as Montagny by Jean-Baptiste Perronneau (1757 to 1758)

And so, placed next to it is a very good pastel portrait of her daughter Julie by Morisot:

Again, the Morisot doesn’t have the astonishing finish or visual depth of the Perronneau. And yet, in its very sketchiness, it indicates an infinitely more modern consciousness, a proto-modern sensibility made of gaps and fragments, the strange ellipses and leaps of consciousness which modernist literature was about to start exploring about a decade later (I’m thinking about the earliest works of Kafka and Joyce).

The French eighteenth century

So, as mentioned above, the exhibition is worth visiting to see not just works by Morisot, but also (an admittedly small) number of works by French eighteenth century masters. There’s a pretty poor portrait of a young girl by Fragonard but a dazzling work by Watteau:

Completely different in style from those guy’s frothy confections and commedia dell’arte whimsy, there’s a lovely piece by the master of eighteenth century realism, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, The Scullery Maid, a characteristically humble domestic scene of a serving maid getting eggs out of a jug surrounded by beautifully depicted bowls and servant-level bric-a-brac.

This leads off in another direction because it turns out that Morisot’s sister, Edma, was also an artist and she is represented here by just one work, a beautiful landscape in the manner of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot who both girls had studied under. These are all delights.

The English connection

But back to the English. The exhibition explains that Morisot spent her honeymoon (with Manet’s brother, Eugène) on a trip which took in the joys of the Isle of Wight and then London. In London she saw the huge collection amassed by Sir Richard Wallace, Marquess of Hertford, which has been preserved for the nation as the Wallace Collection.

It was here that she was introduced to the works of 18th century English masters such as Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and George Romney. The exhibition takes a little detour to explain the different styles of these three men, and discuss some key works by each of them, and then how their styles or motifs found their way into Morisot’s work.

Gainsborough is the most obviously close to Morisot because of his light, feathery, sketchy approach, which drew criticism from the more grand and finished Reynolds, yet was precisely the quality that attracted the quick, sketchy Frenchwoman.

Installation view of ‘Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism’ at Dulwich Picture Gallery, setting ‘Mrs Mary Robinson’ by George Romney (1781, on the left) against ‘Winter, or Woman with a Muff’ by Berthe Morisot (1880)

Summary

Not all of Morisot’s work is great. The fourth and final room contains only works by her and I have to admit I didn’t like most of them.

Worthy depictions of domestic interiors, of her growing daughter, intimate portraits of women outside in the Bois de Boulogne or out in a boat or resting on divans (clearly a full-time occupation for many Victorian ladies), I often found their style either washed-out (several of the supposedly sweet and intimate studies of her daughter gave her such a yellow-pale face she looked like a corpse, for example, ‘Children with a basin‘) or so quick and sketchy as to feel amateurish.

Very good amateurish, but in many of her paintings the multiple clumsinesses wherever I looked just stopped me really enjoying them, giving in, surrendering, saying Yes.

By contrast, I was enraptured by almost all the eighteenth century works (except for the ghastly, ugly Fragonard in room one), by her sister’s one work, and also by the massive work by a painter I haven’t mentioned yet, her contemporary James Tissot (The Ball on Shipboard), included because Tissot moved from Paris to London and made a great success of his career, so much so that, on her honeymoon trip, Morisot seriously considered doing the same and moving to London.

Even the 18th century ‘cartoons’ or preliminary sketches for big works like by Boucher (‘Vulcan’s Forge) delighted and enchanted with a depth and finish and wonderful technique, in a way that most of the Morisot didn’t.

For this reason I hardly think it the scandal of the century that Morisot isn’t as well known as many of the other impressionists. To be blunt, I don’t think she’s as good. Or definitely not on the strength of the works presented here, a handful of which are really good, some are pretty good, and some are positively poor.

But then again, it depends on your aesthetic. Did my general preference for the 18th century works indicate that I’m a peasant, a man of poor taste, a liker of pretty pictures and chocolate box art, who doesn’t appreciate more demanding (and hardly that demanding) art?

Here’s a test. Here’s the bold, take-no-prisoners self-portrait which the curators open the show with.

I get that she’s a strong independent woman, and that this comes over not only in the directness of her gaze but in the super-confidence with which she didn’t finish it. The French have an expression, ‘je-m’en-foutisme’, which translates as ‘I don’t give a damn-ism’ (or ruder, four-letter equivalents).

So, is the scrappy finish and the lack of immediate visual appeal outweighed by the strength of character and psychological depth of a painting like this? Your answer will determine whether you like Morisot, or at least the selection of 30 or so Morisot paintings to be found in this small but incredibly stimulating and hugely enjoyable exhibition.

The merch

I’ve made the point in previous reviews of Impressionist exhibitions, but one reason for the ongoing popularity of the Impressionists is simply that their paintings transfer so well onto posters and mugs and tea towels and jigsaws and the whole world of merchandise. Painting which, large and in the flesh feel half finished and scrappy, when reduced to the size of a coffee cup or tea tray, suddenly look finished, light and attractive. Never ceases to amaze me. As you can see from the full range of Morisot merchandise on sale at the Dulwich Picture Gallery shop:

The promotional video

Related links

- Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism continues at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 10 September 2023

Related reviews

- Impressionists by Antonia Cunningham (2001)

- The Private Lives of the Impressionists by Sue Roe (2006)

- 50 Women Artists You Should Know (2008)

- Women, Art and Society by Whitney Chadwick (2012)