How to say Oceania

First the pronunciation. All the curators and scholars on the audio-guide (£2.50 and well worth it) pronounced it: O-SHE-EH-KNEE-ER. They are mostly Oceanians (Auusies and Kiwis) themselves. Whereas Tim Marlow, RA artistic director, pronounces it: O-SHE-ARE-KNEE-ER. Maybe that’s the British pronunciation.

The map

Second, the map. Oceania is immense, covering – at its widest extent, about a third of the earth’s surface. Yet it is almost all water. Apart from the continent of Australia, the big islands of New Guinea and New Zealand, it mainly comprises hundreds of small to tiny islands or atolls, scattered over the immensity of the Pacific Ocean.

It was only later that European geographers divided the vast area into Polynesia (Greek for ‘many islands’), Melanesia (meaning ‘islands of black people’) and Micronesia (‘small islands’).

The people

It took a vast period of time for them to be settled. Indigenous Australians migrated from Africa to Asia around 70,000 years ago, and arrived in Australia around 50,000 years ago. Papua New Guinea was first colonised 30,000 years ago.

But most of the islands of Oceania were populated a lot later (or more recently), starting maybe around 3,000 to 3,500 BC on Fiji, 1400 BC in the Bismarck Archipelago, 1000 BC on Tonga, 300 to 400 AD for Easter Island and Hawaii, New Zealand between 800 and 1200 AD.

So the problem any exhibition of ‘Oceania’ faces is this extraordinary diversity of histories, cultures, languages and religions to be found over this vast extent.

The timeline

It can be simplified as:

- Tribal peoples travel across the islands, settling them over a huge time span from 50,000 BC to 400 AD.

- European discovery: various Pacific islands were ‘discovered’ from the 16th century onwards by European explorers from Portugal, Spain and Holland (e.g. the Dutchman Abel Tasman who gave his name to Tasmania in 1642). But Anglocentric narratives tend to focus on the four voyages of Captain James Cook, the first of which arrived at Tahiti in 1769 with Cook going on to map the islands of the Pacific more extensively than any man before or since.

- Colonisation: during the 19th century one by one the islands fell under the control of European powers, namely Britain and France and Holland, with Germany arriving late in the 19th century and then America seizing various islands at the turn of the 20th century. Everywhere Europeans tried to impose European law, brought missionaries who tried to stamp out tribal customs, sometimes used the people as forced labour, and everywhere brought diseases like smallpox which devastated native populations.

- Political awakening: during my lifetime i.e. the last 30 or 40 years, the voices of native peoples in all the islands have been increasingly heard, fighting for political independence, demanding reparations for colonial-era injustices, a great resurgence of cultural and artistic activity by native peoples determined to have their own stories heard, and a great wind of change through western institutions and audiences now made to feel guilty about their colonial legacy, and invited to ask questions about whether we should return all the objects in our museums to their original owners.

- Global warming: unfortunately, at the same time as this great artistic and political awakening has taken place, we have learned that humanity is heating up the world, sea-levels will rise and that a lot of Oceania’s sacred places, historic sites and even entire islands are almost certainly going to be submerged and lost.

The peg for the exhibition

250 years ago, in August 1768, the Royal Academy was founded by George III. Four months earlier, Captain James Cook had set off on his epoch-making expedition to the Pacific. This exhibition celebrates this thought-provoking junction of events.

The exhibition itself

I love tribal art, native art, primitive art, whatever the correct terminology is. Some of my favourite art anywhere is the Benin Bronzes now in the British Museum (and other European collections), so I should have loved this exhibition. There are well over a hundred carved canoes, masks, statues, spears and paddles, totems, roof beams, and other ‘native’ or ‘tribal’ objects which emanate tremendous artistic power and integrity.

Tene Waitere, Tā Moko panel (1896 to 1899) Te Papa © Image courtesy of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

I think one of the problems is that I found it, in fact, too immense. Overwhelmed by wall after wall of extraordinary masks and carvings I found the narrative or explanations behind the objects difficult to follow. It is the challenge of ‘Oceania’ as a subject that it is so huge and so diverse. Every single island had its own peoples, with their own myths, legends, traditions and ways. It wasn’t like reading about the ancient Greeks or Egyptians which are reasonably uniform and stable entities – it was like reading about a thousand types of ancient Greek or Egyptians.

The exhibition attempts to create order from this profusion by allotting objects to themed rooms, thus:

1. Introduction

A huge map of Oceania takes up one wall of the central octagonal room, whose other dominating feature is a vast cascading blue curtain, a work of art invoking the enormous Pacific made by the Mata Aho Collective of four Māori women. And on another wall, a video of Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner from the Marshall Islands reciting one of her poems in a strong American accent.

2. Voyaging and navigation

This room contains some breath-takingly beautiful carved wooden canoes, paddles, prows, fierce wooden headposts, ornate carvings and painted figureheads. In the background, on the left, you can see a display case which contains several of the ‘stick charts’ which native peoples used as navigational aids.

Tupai, a native from Tahiti, who I learned about when I read the biography of Captain Cook, was a native who joined Cook’s crew and became extremely useful as an interpreter with tribes on the islands he visited. Tupai made a number of drawings of natives and Europeans and these and a number of other drawings are scattered throughout the show. interesting, but dwarfed by the visual and imaginative impact of the enormous canoes and masks and statues.

3. Expanding horizons

Spears, head dresses, statues, ceremonial clubs and dance shields.

The commentary makes the point that a lot of the artefacts now on display in Western museums were not stolen and looted. Most Oceanic cultures placed importance on gift-giving for cementing alliances, mediating power, exchanging brides and grooms, and so on. Hence a lot of the stuff on show here was given freely by native peoples keen to establish their idea of good relationships with the newcomers by exchanging. And of course, the European ships exchanged or ‘sold’ to the natives all sorts of European goods, from trashy gewgaws, to useful tools and equipment.

4. Place a community

A room about buildings showing how native peoples decorated their buildings with paintings or carvings depicting myths, legends, important ancestors, and how the architecture not only mediated space, but also, in some sense, controlled time. For example as you entered a chamber decorated with carvings of your ancestors, you were literally going back to their time.

This room included one of the highlights, an enormous long, carved, wooden roofbeam from the Solomon Islands which featured some exquisitely carved figures of seagulls, pinned tail up to the side of the wall, as if diving down to catch the wooden fish depicted swimming along beneath them.

Also included were some fairly explicit images of the sexes, a number of men with penis sheathes and the goddess Dikulai carved with her legs wide apart and, apparently, pulling apart her labia.

5. Gods and ancestors

This is another room full of enormous carved wooden and stone statues, for example of the two-headed figure of Ti’i from Tahiti, or the immense stone Maori figure of Hava Rapi Nui. There’s a wooden depiction of Lono, the Hawaiian god who was to be Captain Cook’s nemesis.

6. The spirit of the gift

Examples of the gifts whose exchange was such an important part of the culture of many of the islands: necklaces made of teeth or shells, armshells, half a dozen enormous decorated barkcloths the size of Persian carpets, cloaks made of feathers or flax, and a couple of three-foot-tall, feathered godheads.

7. Performance and memory

Most of these artefacts were not ‘art’ in our sense, objects to be kept hanging on a wall or in sterile conditions in galleries. Most of them were made to be used – to be worn, moved or swung, in an atmosphere of incense and music and celebration, or commemoration or ritual.

Objects like a lifesize costume for a ‘chief mourner’, or the huge display of fans, figures, masks, a dance paddle, a head crest, carved wooden shields, a war club, a ceremonial adze, a crocodile mask. Things that were meant to come alive in the hands of experienced users.

8. Encounter and empire

Here come the horrible Europeans bringing their Christianity, their ‘rule of law’ and their ideas of ‘private property’ which could be bought and sold at a profit, instead of freely exchanged as gifts.

That said, the exhibition emphasises how native peoples used all the new objects and materials which Europeans exchanged with them to produce new hybrid forms of art, incorporating European materials and motifs, precursors, in some ways, to tourist souvenirs.

In the enormous display case which took up one entire wall and housed some 15 stunning carved objects, pride of place went to another long slender carving, this time of a feast trough carved in the shape of a crocodile, from Kalikongu, a village in the West Solomon Islands.

19th-century feast bowl from the Solomon Islands, nearly 7 metres long. Photograph: Trustees of the British Museum

9. In pursuit of Venus (infected)

The exhibition completely changes tone as you round the corner and come across the longest continuous video projection I’ve ever seen. Onto the wall of the longest room in the Royal Academy is projected this 21st century live-action animated art work by Lisa Reihana, a 26-metre wide, 32-minute long installation. To quote from Reihana’s website:

In 1804, Joseph Dufour created Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, a sophisticated 20-panel scenic wallpaper whose exotic subject matter referenced popular illustrations of the times and mirrored a widespread fascination with Captain Cook and de la Perouse Pacific voyages. Two hundred years later Lisa Reihana reanimates this popular wallpaper as a panoramic video spanning a width of 26 metres.

While Dufour’s work models Enlightenment beliefs of harmony amidst mankind, Reihana’s version includes encounters between Polynesians and Europeans which acknowledge the nuances and complexities of cultural identities and colonisation. Stereotypes about other cultures and representation that developed during those times and since are challenged, and the gaze of imperialism is returned with a speculative twist that disrupts notions of beauty, authenticity, history and myth.

If you’re puzzled by the title, it is explained by the fact that Captain Cook’s 1768 voyage to the Pacific was commissioned by the Royal Society to record the transit of Venus, a phenomenon it was hoped would help improve navigation, and which astronomers knew would be better observed from the South Pacific than from Britain.

The subtitle, ‘infected’, rather brutally reminds us of the immense devastation wrought on native populations by the disease-bringing Europeans (whose diseases had earlier ravaged the populations of the Caribbean, north and central America).

Here’s a clip from In pursuit of Venus (infected):

The film presents a panorama of all kinds of social interactions from the colonising period including, inevitably, scenes of brutality and killing.

For me this completely changed the tone of the exhibition. Up till then I had been admiring Oceanic culture from the past: from this point onwards, for the last two rooms, the exhibition transitions to being about contemporary art by contemporary artists from the Oceanic region, a different thing entirely.

A completely different thing because these artists, without exception, being 21st century artists, employ what is now the universal, global language of contemporary art. They may have been born in New Zealand or the Marshall Islands, but they have been educated into the international visual language of contemporary art from New York to Beijing.

Thus a lot of their visual and artistic distinctiveness was lost.

10. Memory

These last two rooms mix a handful of awesome traditional masks or wood carvings with bang up-to-date contemporary works of art.

For example, The Pressure of Sunlight Falling by Fiona Partington (b.1961 New Zealand) consists of five enormous digital photographs of casts made of the heads of Pacific people. The work is based on the fact that, on the Pacific voyage of French explorer Dumont d’Urville, from 1837 to 1840, the eminent phrenologist, Pierre-Marie Dumoutier, took life casts of natives that the expedition encountered. Centuries later, Pardington heard about this, and dug around in the archives to discover some of the original casts. In the words of the catalogue, she:

reinvests their mana by highlighting their neoclassical dignity and beauty through immaculate lighting and composition.

This is all well and good and interesting. And the photos are stunning.

But for me they come from the world of contemporary art, they could be hanging in the Serpentine or Whitechapel or ABP gallery – all of which are worlds away from the anthropological imagination required to imagine yourself into a Maori canoe or a Solomon Island hut filled with wood carvings of the ancestors.

11. Memory and commemoration

The final room contains a couple of ‘tribal’ works, but the balance has now shifted decisively towards very contemporary Oceanic art.

These include Blood Generation (2009), a collaboration between artist Taloi Havini and photographer Stuart Miller. Between 1988 and 1998 there was a brutal civil war between Papua New Guinea and the people of Bougainville, triggered by external interests in mining. The young people who grew up during this era are known locally as the ‘blood generation’. The art work consists of a series of brooding, mostly black and white, photos of young people from the blood generation and the mine-scarred landscape they grew up in.

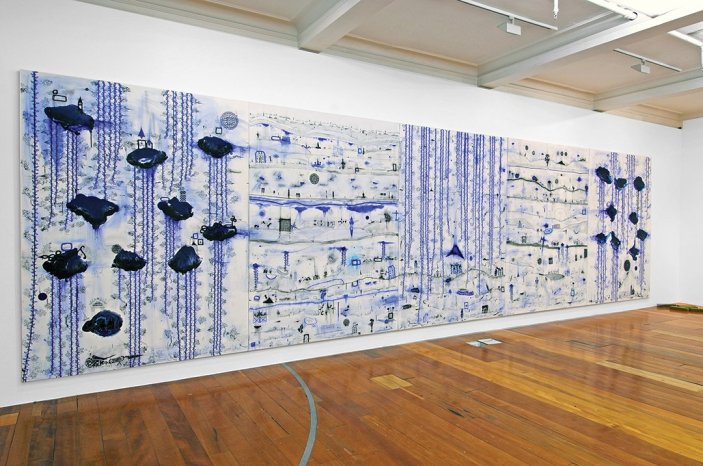

One whole wall of this last room is devoted to an enormous painting on canvas, Kehe tau hauaga foou (To all new arrivals) by John Pule (2007).

And a video, Siva in motion, in which video artist Yuki Kihara is dressed in a black Victorian dress, and then slowly performs dance movements traditionally ascribed to the Hindu god Siva. The work is in memory of the 159 victims of the 2009 tsunami, which is why it is in the room devoted to ‘Memory and commemoration’.

I hope you can see why, by the end of these eleven rooms packed with geography, history, new peoples and languages and gods and customs and traditions, I felt that these final, absolutely contemporary art works, though they may well bring an exhibition of Oceanic art right up to date, also threw me.

They had the regrettable effect of overwriting much of the visual impact of the native objects I’d seen earlier in the exhibition. Photography and video are so powerful that they tend to blot out everything else.

I wish I’d stopped at room eight, among the amazing carved head and feathered masks and strange threatening statues, and kept the strange, powerful, haunting lost world of Oceania with me for the rest of the day.

Video

The RA did a live broadcast from the opening of the exhibition, featuring Tim Marlow, RA artistic director and scholars discussing artefacts, and also including a live performance.

Related links

- Oceania continues at the Royal Academy until 10 December 2018

Reviews about the Pacific

- South Sea Tales by Robert Louis Stevenson (1895)

- The Moon and Sixpence by W. Somerset Maugham (1919) (partly set in Tahiti)

- The Narrow Corner by W. Somerset Maugham (1932) (set among Pacific islands)

- Solomon’s Seal by Hammond Innes (1980) (adventure thriller set during a coup on Bougainville)