It should not be too difficult to arrange my escape and then I shall return to the solitary church in that enchanted world, where by day fantastic birds fly through the petrified forest and jewelled crocodiles glitter like heraldic salamanders on the banks of the crystalline rivers, and where by night the illuminated man races among the trees, his arms like golden cartwheels and his head like a spectral crown… (p.169)

This is a novel of staggering, visionary brilliance, whose otherworldly vividness is matched only by the eerily detached and psychological flatness of all the human characters.

Ballard’s third canonical novel (he suppressed his first effort, The Wind From Nowhere) is another disaster scenario which slowly unfolds, creating an ’emergency zone’ where ordinary or rational notions of time and order and comprehensible behaviour slowly collapse.

The protagonist is another fictional doctor (Dr Kerans in The Drowned World, Dr Ransom in The Drought, Dr Edward Sanders in this one) who finds himself drawn towards the danger zone, becoming briefly entangled with an eligible young woman, but far more attracted to the area of collapse because he subconsciously knows it will release him from reason, from social relations, from his past.

And so he becomes another Ballard protagonist on a journey towards the area of decay, to an abandoned city strewn with derelict cars, empty hotels, eerie shopwindow mannequins and always, everywhere, the drained swimming pools and dried-up fountains.

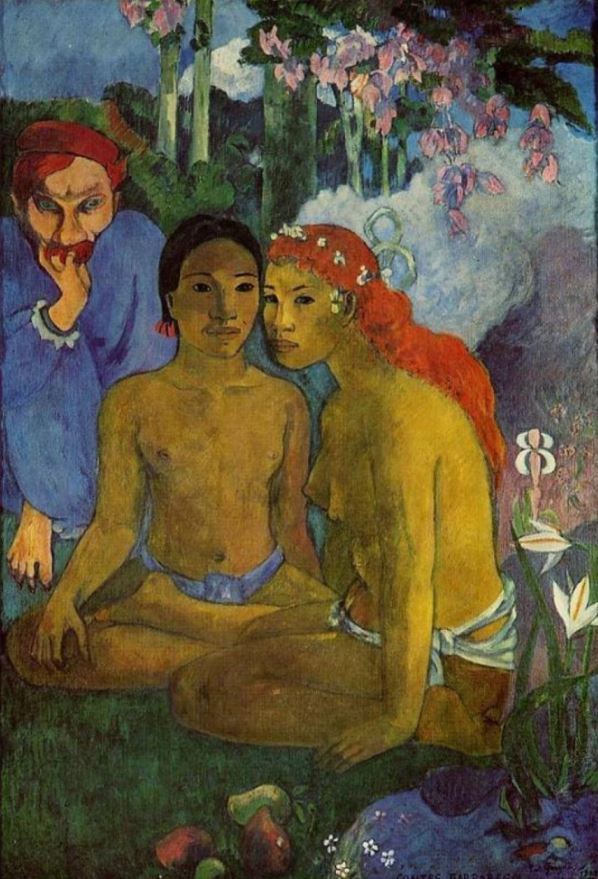

And it’s another Ballard novel which references a haunting painting which in many ways seems to have been its inspiration – Isle of the Dead by the Swiss Symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin for this novel, as Yves Tanguy’s painting Jours de Lenteur (1937) was a visual spur for The Drought.

Part one – The Equinox

Dr Edward Sanders is 40. For fifteen years he has been working in Africa, for the past ten at the Fort Isabelle leper hospital in the Cameroon. He has been having an affair with the wife of one of his colleagues, a microbiologist named Max Clair, the wife’s name being Suzanne Clair.

Three months ago the Clairs had, without explanation, abruptly quit the leper hospital, and gone to the town of Mont Royal, close to some jewel-mining operations. Mont Royal is upriver of the coastal town of Port Matarre. Then Sanders receives a letter from Suzanne telling him the forest is ‘full of jewels’. For obscure reasons, uncertain (like most Ballard protagonists) of his own motivation, Sanders takes a month’s leave from the hospital to go and see the Clairs.

The novel opens as the steamer Sanders is travelling on from Libreville (the modern-day capital city of Gabon) arrives at Port Matarre. On board he has struck up relations with two typically queer, aloof and puzzling characters, the Catholic priest Father Balthus, and a short intense man he is forced to share a cabin with, Ventress. He steps ashore on the day of the spring equinox – darkness and light are perfectly balanced.

Sanders quickly discovers something strange is going on. There are no river steamers up to Mont Royal. The railway is closed. The roads are closed. The telegraph is down. He visits the military chief of the area who tells him that news is being… rationed.

He notices the sky is eerily dark and the jungle across the river and surrounding the town has a sombre, colourless feel about it.

Then Sanders gets caught up in a James Bond-style shootout down at the native harbour. At the centre of it is Ventress carrying a suitcase he’s at great pains to protect from a gang of machete- and gun-toting thugs seemingly under the command of a tall blonde-haired man who directs operations from a cruiser which steers up into the docks. Ventress escapes, a dazed Sanders staggers back to his hotel.

After just a few days in town Sanders has picked up a characteristically featureless Ballardian woman, the journalist Louise Peret, who has got wind of something happening up-country and knows there’s a story in it. Down at the docks, before the fight kicked off, she had identified a body the locals were just pulling from the river. It was the assistant to an American journalist who’d gone up country before her.

The thing is – the dead man’s arm was encased in a crystalline sheath which glittered and emitted a strange light. Earlier in the day, in the local market, Sanders had come across a trader who opened a secret cache of flowers, each of which was encased in a brilliant, multi-faceted crystal, freezing cold to the touch.

The night before Sanders had looked up into the sky and seen an extraordinarily bright white object moving over the night sky. He realised it is the telecoms satellite Echo but…shining with an eerie efflorescence as if… encased in jewels...

And so, the secret of the novel leaks out. Somewhere close to Mont Royal the jungle is turning to crystal. As the story progresses, other characters tell him the same process is being reported in the Florida Everglades and the Pripet Marshes of Russia. I.e. across the world.

Sanders strikes a deal with a local, one Captain Aragon, who takes him in his river cruiser up the African river into the heart of… crystals. The comparisons with Conrad’s most famous novel are too obvious to make. After a few days’ vividly described chuntering up the jungley river they come to a pontoon blocking their way and a busy army base. Aragon docks the ship and Sanders makes himself known to the officer in charge, one Captain Radek, himself a doctor (p.63).

Sanders is surprised to see none other than Ventress coming ashore from another boat which has docked at the military base. What’s he doing here? Radek allows Sanders to join an ‘inspection party’ which is proceeding up the river towards Mont Royal. As you might expect, they soon come to stretches where the forest has been turned into crystals whose facets flash light.

Then they arrive at the abandoned city of Mont Royal (like the abandoned London of The Drowned World, the abandoned Mount Royal in The Drought). They dock and the inspection party splits up into groups of soldiers, each led by an NCO. Sanders wanders through the characteristic Ballardian landscape of the abandoned city, cars strewn around the roads, shops eerily deserted and drained swimming pools and empty fountains.

They arrive right at the edge of the crystal zone, and watch an army helicopter trying to fly over it, whose rotors suddenly start crystallising, causing it to crash.

Sanders watches fascinated as an eddy of light passes out of the forest and towards him, crystallising the vegetation all around him, including a nearby car, while his own clothes begin to grow frostings and rimes of crystal, and suddenly a man is yelling at him from the window of a nearby mansion.

The ‘scientific’ explanation

Part two opens with a pretty crude bit of explication. Ballard includes an excerpt from a letter supposedly written by Sanders to the head of the leper hospital, Dr Paul Derain, which gives a comprehensive explanation for the crystallising phenomenon (rather as the ‘scientific’ explanation for both the drought and the drowned world are delayed until we’re well into the story).

It doesn’t make complete sense but the crucial fact is the explanation is based on TIME.

The discovery of anti-matter posits the existence of anti-time. We suspect that anti-matter and matter destroy each other continuously throughout the universe. Well, in the same way, time must be meeting anti-time and annihilating itself. And as time is destroyed, the universe’s total quotient of time decreases so that – like a super-saturated solution – the remaining atoms and molecules are crystallising out ‘in an attempt to secure their foot-hold upon existence’ (p.85).

In the letter Sanders explains that the weird effects he sees around him are connected to events in distant star systems, which astronomers have been observing, of entire systems like the island galaxy M31 becoming crystal, appearing to double in size and brilliancy. Events here in the forests of Africa are intimately linked with disturbances around the universe. (In fact the letter includes a reference to the Everglades in Florida which have, by the time he writes the letter, become almost entirely crystallised with the result that some three million Americans have had to flee their homes.)

Part two – The Illuminated Man

Then the narrative reverts the ‘present’ – in fact right back to the cliffhanger moment which part one ended on – Sanders on the verge of the crystallising zone when he hears someone shout his name from a nearby mansion. He runs across the crystallising grass to find Ventress with a shotgun, hiding behind a window. The reason becomes clear when someone takes a shot at them through the window and then Sanders, venturing downstairs is attacked by the same mulatto and crew of thugs who he’d saved Ventress from back in the fight at the native docks in part one.

Ventress appears to be locked in a feud with the mine-owner Thorensen. Why? He doesn’t explain, continuing to speak in what Sanders describes as ‘his ambiguous and disjointed way’ – so Sanders can’t guess why they appear to be ready to kill each other. (All this reminds me of the inexplicable feud between Whitman and Jonas in The Drought – as if there are people who just want to kill each other, sometimes for reasons they can’t even remember.)

After the shootout in the mansion, Ventress and Sanders venture out into the open and make their way along the half-crystallised river. Then they come across the wreckage of the crashed helicopter, ‘the four twisted blades veined and frosted like the wings of a giant dragonfly’ (p.96). Under the wreckage is an almost entirely crystallised body, it is Radek, the army doctor who greeted Sanders. The latter tears him free from his crystal sheaths and then ties his body to a handy broken tree trunk with his belt and gently pushes it into the river to send downstream and hopefully out of harm’s way.

Then Sanders and Ventress come to an isolated summer house, covered in crystals like a frosted wedding cake. As they approach there are shots, confusion, Ventress is trapped in a net by Thorensen’s men, and a huge Negro approaches with a panga to finish him off, but the surface of the frozen river cracks and gives way under his weight and while he’s extricating himself, Ventress wriggles free and escapes.

Now Sanders is with Thorensen who slowly realises who he is and reluctantly takes him through into the summer house where he is introduced to Serena. Now we learn that Serena is the hapless young who Ventress bullied her poor colonialist parents into letting him marry, then took off to a remote cabin in the forest. Ventress treated her appallingly and Thorensen stole her away whereupon Ventress went mad and has spent six months in an asylum. Now he has returned to take his revenge and steal back his child bride.

So that’s the basis of Ventress and Thorensen’s endless feud. Sanders looks down at Serena lying pale and frail in bed. She’s obviously very ill. Thorensen gives her some of the gems he picked up after the fight at the white mansion. Now Sanders witnesses something amazing which is that the jewels retard the crystallising effects. It is as if concealed in their hears they have the concentrated time which can reverse the time sickness which is causing the crystallisation.

Sanders says he must get back to Port Matarre. Thorensen says he’ll send him there with two of his African trackers. So off they set but after a while, Sanders realises they’re going round in circles. In fact Thorensen is using him as bait to lure Ventress out of hiding just as Ventress used him as bait at the mansion.

The guides disappear leaving Sanders on his own but moments later he hears a firefight in the jungle and goes back to find one of the blacks dying of gunshot wounds. Terrified by all this, Sanders takes off back in the direction of the river. it is heavily crystallised but he hopes to walk along the hard surface back towards the town.

Suddenly he sees a man carrying a wooden burden and hopes it is a soldier foraging for wood but on getting closer is horrified to see that it is Radek who he tried to save. Now most of the crystals have melted in the fast-flowing river Sanders realises that when he tore Radek from from the crystallised ground he ripped half his chest and face off! The man is a bleeding wreck of a man who can’t see and can barely talk but he has just enough energy to bed Sanders – Take me… back. Take me back!’ Sanders dodges the weaving figure and runs for the river, diving into its now free-flowing shallows.

A few hours later he emerges from the river where the road leads to a white building, the Bourbon Hotel. He is back in civilisation. Soldiers greet him and radio base. Captain Aragon turns up and tells him Louise Peret is waiting for him. Not only that but Mr and Mrs Clair – his friend and the friend’s wife who he was having an affair with – are at the hotel, too.

Sanders is greeted by Max, has a shower, changes into new clothes (admittedly the washed clothes of a man who died in the crystal forest) and has civilised drinks with Max and Suzanne. When they discuss Sanders’s adventures in the forest it becomes clear that Suzanne is entranced by the forest and its world of brilliantly-coloured jewelled facets.

Max tactfully beats a retreat (by implication, knowing his wife and best friend have had an affair) and it is only when he’s let alone with her that Sanders realises that Suzanne is showing the first symptoms of leprosy! So that’s why she and Max made such a sudden exit from the Fort Isabelle leper hospital. And there was he thinking it was him and their affair. Wrong again.

Next morning Sanders is bewildered to see that, although Max and Suzanne are overseeing a fairly modern hospital with plenty of resources, the trees and undergrowth are populated by shadowy groups of native lepers. They are refugees from a Catholic leprosie where the priest did little more than pray for them, and are too frightened to come into the modern hospital.

Then Sanders ‘girlfriend’, the beautiful slender journalist Mlle Louise Peret turns up, a breath of fresh air compared to a) the complicated psychodrama playing out around Suzanne and b) the macabre figures of the black lepers hiding in the undergrowth. He takes her to the bungalow the Clairs have lent him, and they make love.

Afterwards, Sanders expands on the ideas of darkness and light, speculating that these polar opposites are coming into sharper relief as time drains away from the world and Louise and he play spot the archetype: she (Louise) is light to Suzanne the dark lady. Thorense and Ventress’s endless feud is somehow binary. Father Balthus, is he darkness and who is his opposite? Sanders? Louise reveals that an army launch is going back up the river and she wants to be on it.

That evening he goes for dinner with Max and Suzanne but instead of discreetly absenting himself afterwards, Max insists on getting out a chessboard and playing a game, while Suzanne retires. An hour or so later the game ends and Sanders walks round the grounds. He sees the outline of the white hotel in the moonlight. He catches a glimpse of Suzanne and makes his way there. He catches up with her and she takes him into the ruined corridors of the abandoned building and up to a second floor room which she has made a kind if refuge.

Here on the bed Sanders makes love to his leprous mistress. The binary black and white imagery is laid on with a trowel. In the afternoon the chalet room was filled with blazing sunlight so he and Louise had to pull down a blind to make love. Now here in the ruined white hotel in the black night he makes love to his dark lady by wan moonlight. They talk. She is suddenly super-sensitive about her disease. She pulls her nightgown around her and before he can stop her runs out the room and down the abandoned corridors

Later that night, back in his chalet, Sanders is awoken by cars being loaded up and searchlights. Max bangs on his door asking if Suzanne is with him. Sanders disclaims all knowledge. Max is almost crying: Suzanne has run off, presumably into the forest. He goes off in search. Sanders takes a group of black servants with him to the Bourbon Hotel but they quickly settle down for a smoke.

Leaving them, Sanders walks back along the road into the abandoned Mont Royal. The crystallising process is much further advanced, the crystals hang from streetlights an overhead wires. Sanders comes across a smashed-in jewellers shop and realises that where the jewels lie on the pavement, the crystals don’t work. It is as if deep within them the jewels contain concentrated time, as well as light, which fights off the time disease of the crystals. Tired, Sanders sits down in the little patch of crystal-free pavement with his back to the wall and fills his pocket with gems.

When he awakes much of the jewels’ power has worn off and he is horrified to find his entire arm up to the shoulder encased in crystals. It is very heavy and very cold. He has been woken by Ventress tugging him. At that moment there is a shot and the window above them shatters. Thorensen and his crew of blacks are upon them. Again. Round and round this feud goes with the pointless circularity of a mad obsession.

Ventress stuffs some of the remaining jewels into Sanders’s pockets and tells him to run, run for his life, keeping in motion is the only thing that will prevent the crystals progressing from his shoulder to neck and thence to his head. And so for hours and hours Sanders runs through the crystallising jungle, The Illuminated Man, windmilling his crystallised arm round and round, gaining a slight relief from the process.

Finally he comes to the crystallised summer house and hears a voice hissing his name. It is Ventress. Again. Hiding in the underside of the summer house, peeking out over the surface of the ground and between pillars at Thorensen’s riverboat which is moored in the river a hundred yards or so away. The black crew load the ship’s cannon and fire repeated volleys at the summer house, the idea being not to destroy it but to shatter the crystals enough for the boar to approach really close. But in the event, after an hour or more of firing, the boat rams hard into the crystals but rears up on its hull and becomes landlocked, the crystals slowly starting to form over it.

This leads to one of the most contrived but strangest moments which is when a vast fifteen-foot crocodile, festooned with crystals lumbers heavily towards the house. Only when it is almost upon them does Sanders realise he can see a gun barrel sticking out of its mouth and realise it is an elaborate costume. He fires point blank into the crocodile which rears up on its hind legs revealing the mulatto who has been a repeated assailant of Ventress’s and Sanders, rearing up, keeling over and dying.

Ventress tells Sanders to go, go now: now all the blacks are dead and it is just him against Thorensen. Go!

And so Sanders staggers through the all-the-time more heavily crystallising jungle until he stumbles across a clearing and discovers the Catholic church of Father Balthus. He stumbles up the aisle and holds his arm up to the enormous jewel-encrusted crucifix and, of course, his arm is freed from its crystals. All the while Father Balthus watches from the organ where he is playing baroque organ music.

For three days Sanders stays with him in their church refuge, eating frugal meals, pumping the bellows for the organ, as his arm slowly heals and Father Balthus gives him his Christina interpretation of the crystallising, namely that the risen Christ is all around them in the new light of the forest. Eventually, the jewel’s power fades and the crystals invade the church and start advancing up the aisle. Balthus pushes the enormous crucifix into Sanders’s hands and tells him to escape. Sanders’s last sight of the priest is of him standing on the verandah of the church, arms outspread in the posture of crucifixion and the crystals move in to embalm him.

through the crystal forest Sanders staggers, using the jewels’ power to melt a path through the by-now almost solid walls in each direction.

1. He comes upon the lepers he’d seen hiding in the undergrowth near the hospital. Now they are dancing in the forest, weaving a strange saraband, old and young, men and woman, children. They dance up to him then away, eerily. And Sanders realises they are led by a tall figure in a black hood and only as it turns away does he realise it is Suzanne, now thoroughly incorporated into her leprous avatar.

2. He stumbles upon the damn summer house, again, now entirely immured in crystals and goes into the bedroom where he sees the corpse of Thorensen, the feud finally over, the bloody hole in his chest from a shotgun wound turned to ornate crystal, lying beside the embalmed Serena, her chest barely moving in its carapace of light. And then sees a figure running past the building, shedding fragments of crystal as it runs, crying out over and over Serena Serena. It is mad Ventress.

Finally, Sanders blunders out of the jungle and into the arms of the troops waiting at the perimeter. Ironically, he is charged with looting the enormous crucifix, until Max and Louise intervene with the authorities.

Now, it is two months later in Port Matarre and he winds up his letter to the director of his leprosie, Dr Paul Derain. He casually mentions that he thinks he has seen an efflorescence of the sun and its surface crossed by a distinctive lattice-work, a vast portcullis which may one day reach out and crystallise the planets themselves, stopping them in their tracks.

Louise has looked after him but he has not really been there, his heart is in the crystal forest and so she has grown away from him. Max asks him to come and work at the new hospital, but Sanders isn’t interested. He finishes writing the letter and leaves it to be posted, settles his bill and walks down to the quayside. Captain Aragon and his launch putters by, the two men nodding to each other. They reach an understanding. Half an hour later the launch turns and heads upriver, taking Sanders back into the heart of the crystal forest and his destiny.

He is coolly watched by Max and Louise from the quayside, but what do they understand of what he and Suzanne discovered, that

the only resolution of the imbalance within their minds, their inclination towards the dark side of the equinox, could be found within that crystal world. (p.173)

Related links

Reviews of other Ballard books

Novels

- The Drowned World (1962)

- The Drought (1964)

- The Crystal World (1966)

- Some style features of the early novels of J.G. Ballard

- J.G. Ballard’s literary experimentalism

- The Atrocity Exhibition (1970)

- Preface to the French edition of Crash

- Crash (1973)

- Pornography, simile and surrealism in The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash

- Concrete Island (1974)

- High Rise (1975)

- The Unlimited Dream Company (1979)

- Hello America (1982)

Short story collections

- The Voices of Time and Other Stories (1962)

- The Terminal Beach (1964)

- The Disaster Area (1967)

- Vermilion Sands (1971)

- Low-Flying Aircraft and Other Stories (1976)

- The Venus Hunters (1980)

- Myths of the Near Future (1982)

Other science fiction reviews

Late Victorian

1888 Looking Backward 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy – Julian West wakes up in the year 2000 to discover a peaceful revolution has ushered in a society of state planning, equality and contentment

1890 News from Nowhere by William Morris – waking from a long sleep, William Guest is shown round a London transformed into villages of contented craftsmen

1895 The Time Machine by H.G. Wells – the unnamed inventor and time traveller tells his dinner party guests the story of his adventure among the Eloi and the Morlocks in the year 802,701

1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells – Edward Prendick is stranded on a remote island where he discovers the ‘owner’, Dr Gustave Moreau, is experimentally creating human-animal hybrids

1897 The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells – an embittered young scientist, Griffin, makes himself invisible, starting with comic capers in a Sussex village, and ending with demented murders

1899 When The Sleeper Wakes/The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells – Graham awakes in the year 2100 to find himself at the centre of a revolution to overthrow the repressive society of the future

1899 A Story of the Days To Come by H.G. Wells – set in the same future London as The Sleeper Wakes, Denton and Elizabeth defy her wealthy family in order to marry, fall into poverty, and experience life as serfs in the Underground city run by the sinister Labour Corps

1900s

1901 The First Men in the Moon by H.G. Wells – Mr Bedford and Mr Cavor use the invention of ‘Cavorite’ to fly to the moon and discover the underground civilisation of the Selenites

1904 The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth by H.G. Wells – scientists invent a compound which makes plants, animals and humans grow to giant size, prompting giant humans to rebel against the ‘little people’

1905 With the Night Mail by Rudyard Kipling – it is 2000 and the narrator accompanies a GPO airship across the Atlantic

1906 In the Days of the Comet by H.G. Wells – a comet passes through earth’s atmosphere and brings about ‘the Great Change’, inaugurating an era of wisdom and fairness, as told by narrator Willie Leadford

1908 The War in the Air by H.G. Wells – Bert Smallways, a bicycle-repairman from Kent, gets caught up in the outbreak of the war in the air which brings Western civilisation to an end

1909 The Machine Stops by E.M. Foster – people of the future live in underground cells regulated by ‘the Machine’ until one of them rebels

1910s

1912 The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Professor Challenger leads an expedition to a plateau in the Amazon rainforest where prehistoric animals still exist

1912 As Easy as ABC by Rudyard Kipling – set in 2065 in a world characterised by isolation and privacy, forces from the ABC are sent to suppress an outbreak of ‘crowdism’

1913 The Horror of the Heights by Arthur Conan Doyle – airman Captain Joyce-Armstrong flies higher than anyone before him and discovers the upper atmosphere is inhabited by vast jellyfish-like monsters

1914 The World Set Free by H.G. Wells – A history of the future in which the devastation of an atomic war leads to the creation of a World Government, told via a number of characters who are central to the change

1918 The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs – a trilogy of pulp novellas in which all-American heroes battle ape-men and dinosaurs on a lost island in the Antarctic

1920s

1921 We by Evgeny Zamyatin – like everyone else in the dystopian future of OneState, D-503 lives life according to the Table of Hours, until I-330 wakens him to the truth

1925 Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov – a Moscow scientist transplants the testicles and pituitary gland of a dead tramp into the body of a stray dog, with disastrous consequences

1927 The Maracot Deep by Arthur Conan Doyle – a scientist, engineer and a hero are trying out a new bathysphere when the wire snaps and they hurtle to the bottom of the sea, where they discover…

1930s

1930 Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon – mind-boggling ‘history’ of the future of mankind over the next two billion years – surely the most sweeping vista of any science fiction book

1938 Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis – baddies Devine and Weston kidnap Oxford academic Ransom and take him in their spherical spaceship to Malacandra, as the natives call the planet Mars

1940s

1943 Perelandra (Voyage to Venus) by C.S. Lewis – Ransom is sent to Perelandra aka Venus, to prevent a second temptation by the Devil and the fall of the planet’s new young inhabitants

1945 That Hideous Strength: A Modern Fairy-Tale for Grown-ups by C.S. Lewis– Ransom assembles a motley crew to combat the rise of an evil corporation which is seeking to overthrow mankind

1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell – after a nuclear war, inhabitants of ruined London are divided into the sheep-like ‘proles’ and members of the Party who are kept under unremitting surveillance

1950s

1950 I, Robot by Isaac Asimov – nine short stories about ‘positronic’ robots, which chart their rise from dumb playmates to controllers of humanity’s destiny

1950 The Martian Chronicles – 13 short stories with 13 linking passages loosely describing mankind’s colonisation of Mars, featuring strange, dreamlike encounters with Martians

1951 Foundation by Isaac Asimov – the first five stories telling the rise of the Foundation created by psychohistorian Hari Seldon to preserve civilisation during the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1951 The Illustrated Man – eighteen short stories which use the future, Mars and Venus as settings for what are essentially earth-bound tales of fantasy and horror

1952 Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov – two long stories which continue the future history of the Foundation set up by psychohistorian Hari Seldon as it faces attack by an Imperial general, and then the menace of the mysterious mutant known only as ‘the Mule’

1953 Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov – concluding part of the Foundation Trilogy, which describes the attempt to preserve civilisation after the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1953 Earthman, Come Home by James Blish – the adventures of New York City, a self-contained space city which wanders the galaxy 2,000 years hence, powered by ‘spindizzy’ technology

1953 Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury – a masterpiece, a terrifying anticipation of a future when books are banned and professional firemen are paid to track down stashes of forbidden books and burn them until one fireman, Guy Montag, rebels

1953 The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester – a breathless novel set in a 24th century New York populated by telepaths and describing the mental collapse of corporate mogul Ben Reich who starts by murdering his rival Craye D’Courtney and becomes progressively more psychotic as he is pursued by telepathic detective, Lincoln Powell

1953 Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke a thrilling narrative involving the ‘Overlords’ who arrive from space to supervise mankind’s transition to the next stage in its evolution

1954 The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov – set 3,000 years in the future when humans have separated into ‘Spacers’ who have colonised 50 other planets, and the overpopulated earth whose inhabitants live in enclosed cities or ‘caves of steel’, and introducing detective Elijah Baley to solve a murder mystery

1956 The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov – 3,000 years in the future detective Elijah Baley returns, with his robot sidekick, R. Daneel Olivaw, to solve a murder mystery on the remote planet of Solaria

— Some problems with Isaac Asimov’s science fiction

1956 They Shall Have Stars by James Blish – explains the invention, in the near future, of i) the anti-death drugs and ii) the spindizzy technology which allow the human race to colonise the galaxy

1956 The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester – a fast-paced phantasmagoria set in the 25th century where humans can teleport, a terrifying new weapon has been invented, and tattooed hard-man, Gulliver Foyle, is looking for revenge

1959 The Triumph of Time by James Blish – concluding novel of Blish’s ‘Okie’ tetralogy in which mayor of New York John Amalfi and his friends are present at the end of the universe

1959 The Sirens of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut – Winston Niles Rumfoord builds a space ship to explore the solar system where encounters a chrono-synclastic infundibula, and this is just the start of a bizarre meandering fantasy which includes the Army of Mars attacking earth and the adventures of Boaz and Unk in the caverns of Mercury

1960s

1961 A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke a pleasure tourbus on the moon is sucked down into a sink of moondust, sparking a race against time to rescue the trapped crew and passengers

1962 The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – Dr Kerans is part of a UN mission to map the lost cities of Europe which have been inundated after solar flares melted the worlds ice caps and glaciers, but finds himself and his colleagues’ minds slowly infiltrated by prehistoric memories of the last time the world was like this, complete with tropical forest and giant lizards, and slowly losing their grasp on reality.

1962 The Voices of Time and Other Stories – Eight of Ballard’s most exquisite stories including the title tale about humanity slowly falling asleep even as they discover how to listen to the voices of time radiating from the mountains and distant stars, or The Cage of Sand where a handful of outcasts hide out in the vast dunes of Martian sand brought to earth as ballast which turned out to contain fatal viruses. Really weird and visionary.

1962 A Life For The Stars by James Blish – third in the Okie series about cities which can fly through space, focusing on the coming of age of kidnapped earther, young Crispin DeFord, aboard space-travelling New York

1962 The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick In an alternative future America lost the Second World War and has been partitioned between Japan and Nazi Germany. The narrative follows a motley crew of characters including a dealer in antique Americana, a German spy who warns a Japanese official about a looming surprise German attack, and a woman determined to track down the reclusive author of a hit book which describes an alternative future in which America won the Second World War

1962 Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut – the memoirs of American Howard W. Campbell Jr. who was raised in Germany and has adventures with Nazis and spies

1963 Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut – what starts out as an amiable picaresque as the narrator, John, tracks down the so-called ‘father of the atom bomb’, Felix Hoenniker for an interview turns into a really bleak, haunting nightmare where an alternative form of water, ice-nine, freezes all water in the world, including the water inside people, killing almost everyone and freezing all water forever

1964 The Drought by J.G. Ballard – It stops raining. Everywhere. Fresh water runs out. Society breaks down and people move en masse to the seaside, where fighting breaks out to get near the water and set up stills. In part two, ten years later, the last remnants of humanity scrape a living on the vast salt flats which rim the continents, until the male protagonist decides to venture back inland to see if any life survives

1964 The Terminal Beach by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s breakthrough collection of 12 short stories which, among more traditional fare, includes mind-blowing descriptions of obsession, hallucination and mental decay set in the present day but exploring what he famously defined as ‘inner space’

1964 Dr. Strangelove, or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb by Peter George – a novelisation of the famous Kubrick film, notable for the prologue written as if by aliens who arrive in the distant future to find an earth utterly destroyed by the events described in the main narrative

1966 Rocannon’s World by Ursula Le Guin – Le Guin’s first novel, a ‘planetary romance’ or ‘science fantasy’ set on Fomalhaut II where ethnographer and ‘starlord’ Gaverel Rocannon rides winged tigers and meets all manner of bizarre foes in his quest to track down the aliens who destroyed his spaceship and killed his colleagues, aided by sword-wielding Lord Mogien and a telepathic Fian

1966 Planet of Exile by Ursula Le Guin – both the ‘farborn’ colonists of planet Werel, and the surrounding tribespeople, the Tevarans, must unite to fight off the marauding Gaal who are migrating south as the planet enters its deep long winter – not a good moment for the farborn leader, Jakob Agat Alterra, to fall in love with Rolery, the beautiful, golden-eyed daughter of the Tevaran chief

1966 – The Crystal World by J.G. Ballard – Dr Sanders journeys up an African river to discover that the jungle is slowly turning into crystals, as does anyone who loiters too long, and becomes enmeshed in the personal psychodramas of a cast of lunatics and obsessives

1967 The Disaster Area by J.G. Ballard – Nine short stories including memorable ones about giant birds, an the man who sees the prehistoric ocean washing over his quite suburb.

1967 City of Illusions by Ursula Le Guin – an unnamed humanoid with yellow cat’s eyes stumbles out of the great Eastern Forest which covers America thousands of years in the future when the human race has been reduced to a pitiful handful of suspicious rednecks or savages living in remote settlements. He is discovered and nursed back to health by a relatively benign commune but then decides he must make his way West in an epic trek across the continent to the fabled city of Es Toch where he will discover his true identity and mankind’s true history

1966 The Anti-Death League by Kingsley Amis –

1968 2001: A Space Odyssey a panoramic narrative which starts with aliens stimulating evolution among the first ape-men and ends with a spaceman being transformed into a galactic consciousness

1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick In 1992 androids are almost indistinguishable from humans except by trained bounty hunters like Rick Deckard who is paid to track down and ‘retire’ escaped ‘andys’ – earning enough to buy mechanical animals, since all real animals died long ago

1969 Ubik by Philip K. Dick In 1992 the world is threatened by mutants with psionic powers who are combated by ‘inertials’. The novel focuses on the weird alternative world experienced by a group of inertials after they are involved in an explosion on the moon

1969 The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin – an envoy from the Ekumen or federation of advanced planets – Genly Ai – is sent to the planet Gethen to persuade its inhabitants to join the federation, but the focus of the book is a mind-expanding exploration of the hermaphroditism of Gethen’s inhabitants, as Genly is forced to undertake a gruelling trek across the planet’s frozen north with the disgraced native lord, Estraven, during which they develop a cross-species respect and, eventually, a kind of love

1969 Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut – Vonnegut’s breakthrough novel in which he manages to combine his personal memories of being an American POW of the Germans and witnessing the bombing of Dresden in the character of Billy Pilgrim, with a science fiction farrago about Tralfamadorians who kidnap Billy and transport him through time and space – and introduces the catchphrase ‘so it goes’

1970s

1970 Tau Zero by Poul Anderson – spaceship Leonora Christine leaves earth with a crew of fifty to discover if humans can colonise any of the planets orbiting the star Beta Virginis, but when its deceleration engines are damaged, the crew realise they need to exit the galaxy altogether in order to find space with low enough radiation to fix the engines – and then a series of unfortunate events mean they find themselves forced to accelerate faster and faster, effectively travelling forwards through time as well as space until they witness the end of the entire universe – one of the most thrilling sci-fi books I’ve ever read

1970 The Atrocity Exhibition by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s best book, a collection of fifteen short experimental texts in stripped-down prose bringing together key obsessions like car crashes, mental breakdown, World War III, media images of atrocities and clinical sex

1971 Vermilion Sands by J.G. Ballard – nine short stories including Ballard’s first, from 1956, most of which follow the same shape, describing the arrival of a mysterious, beguiling woman in the fictional desert resort of Vermilion Sands, the setting for extravagantly surreal tales of the glossy, lurid and bizarre

1971 The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula Le Guin – thirty years in the future (in 2002) America is an overpopulated environmental catastrophe zone where meek and unassuming George Orr discovers that is dreams can alter reality, changing history at will. He comes under the control of visionary neuro-scientist, Dr Haber, who sets about using George’s powers to alter the world for the better with unanticipated and disastrous consequences

1971 Mutant 59: The Plastic Eater by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis – a genetically engineered bacterium starts eating the world’s plastic, leading to harum scarum escapades in disaster-stricken London

1972 The Word for World Is Forest by Ursula Le Guin – novella set on the planet Athshe describing its brutal colonisation by exploitative Terrans (who call it ‘New Tahiti’) and the resistance of the metre-tall, furry, native population of Athsheans, with their culture of dreamtime and singing

1972 The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe – a mind-boggling trio of novellas set on a pair of planets 20 light years away, the stories revolve around the puzzle of whether the supposedly human colonists are, in fact, the descendants of the planets’ shape-shifting aboriginal inhabitants who murdered the first earth colonists and took their places so effectively that they have forgotten the fact and think themselves genuinely human

1973 Crash by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s most ‘controversial’ novel, a searingly intense description of its characters’ obsession with the sexuality of car crashes, wounds and disfigurement

1973 Rendezvous With Rama by Arthur C. Clarke – in 2031 a 50-kilometre-long object of alien origin enters the solar system, so the crew of the spaceship Endeavour are sent to explore it in one of the most haunting and evocative novels of this type ever written

1973 Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut – Vonnegut’s longest and most experimental novel with the barest of plots and characters allowing him to sound off about sex, race, America, environmentalism, with the appearance of his alter ego Kilgore Trout and even Vonnegut himself as a character, all enlivened by Vonnegut’s own naive illustrations and the throwaway catchphrase ‘And so on…’

1974 Concrete Island by J.G. Ballard – the short and powerful novella in which an advertising executive crashes his car onto a stretch of wasteland in the juncture of three motorways, finds he can’t get off it, and slowly adapts to life alongside its current, psychologically damaged inhabitants

1974 Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick – America after the Second World War is a police state but the story is about popular TV host Jason Taverner who is plunged into an alternative version of this world where he is no longer a rich entertainer but down on the streets among the ‘ordinaries’ and on the run from the police. Why? And how can he get back to his storyline?

1974 The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin – in the future and 11 light years from earth, the physicist Shevek travels from the barren, communal, anarchist world of Anarres to its consumer capitalist cousin, Urras, with a message of brotherhood and a revolutionary new discovery which will change everything

1974 Inverted World by Christopher Priest – vivid description of a city on a distant planet which must move forwards on railway tracks constructed by the secretive ‘guilds’ in order not to fall behind the mysterious ‘optimum’ and avoid the fate of being obliterated by the planet’s bizarre lateral distorting, a vivid and disturbing narrative right up until the shock revelation of the last few pages

1975 High Rise by J.G. Ballard – an astonishingly intense and brutal vision of how the middle-class occupants of London’s newest and largest luxury, high-rise development spiral down from petty tiffs and jealousies into increasing alcohol-fuelled mayhem, disintegrating into full-blown civil war before regressing to starvation and cannibalism

1976 Slapstick by Kurt Vonnegut – a madly disorientating story about twin freaks, a future dystopia, shrinking Chinese and communication with the afterlife

1979 The Unlimited Dream Company by J.G. Ballard – a strange combination of banality and visionary weirdness as an unhinged young man crashes his stolen plane in suburban Shepperton, and starts performing magical acts like converting the inhabitants into birds, conjuring up exotic foliage, convinced his is on a mission to liberate them

1979 Jailbird by Kurt Vonnegut – the satirical story of Walter F. Starbuck and the RAMJAC Corps run by Mary Kathleen O’Looney, a baglady from Grand Central Station, among other satirical notions including the new that Kilgore Trout, a character who recurs in most of his novels, is one of the pseudonyms of a fellow prison at the gaol where Starbuck serves a two year sentence, one Dr Robert Fender

1980s

1980 Russian Hide and Seek by Kingsley Amis – set in an England of 2035 after a) the oil has run out and b) a left-wing government left NATO and England was promptly invaded by the Russians – ‘the Pacification’, who have settled down to become a ruling class and treat the native English like 19th century serfs

1980 The Venus Hunters by J.G. Ballard – seven very early and often quite cheesy sci-fi short stories, along with a visionary satire on Vietnam (1969), and then two mature stories from the 1970s which show Ballard’s approach sliding into mannerism

1981 The Golden Age of Science Fiction edited by Kingsley Amis – 17 classic sci-fi stories from what Amis considers the ‘Golden Era’ of the genre, basically the 1950s

1981 Hello America by J.G. Ballard – a hundred years from now an environmental catastrophe has turned America into a vast, arid desert, except for west of the Rockies which has become a rainforest of Amazonian opulence, and it is here that a ragtag band of explorers from old Europe discover a psychopath has crowned himself President Manson, has revived an old nuclear power station in order to light up Las Vegas, and plays roulette in Caesar’s Palace to decide which American city to nuke next

1981 The Affirmation by Christopher Priest – an extraordinarily vivid description of a schizophrenic young man living in London who, to protect against the trauma of his actual life (father died, made redundant, girlfriend committed suicide) invents a fantasy world, the Dream Archipelago, and how it takes over his ‘real’ life

1982 Myths of the Near Future by J.G. Ballard – ten short stories showing Ballard’s range of subject matter from Second World War China to the rusting gantries of Cape Kennedy

1982 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke – Heywood Floyd joins a Russian spaceship on a two-year journey to Jupiter to a) reclaim the abandoned Discovery and b) investigate the monolith on Japetus

1984 Neuromancer by William Gibson – Gibson’s stunning debut novel which establishes the ‘Sprawl’ universe, in which burnt-out cyberspace cowboy, Case, is lured by ex-hooker Molly into a mission led by ex-army colonel Armitage to penetrate the secretive corporation, Tessier-Ashpool, at the bidding of the vast and powerful artificial intelligence, Wintermute

1986 Burning Chrome by William Gibson – ten short stories, three or four set in Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ universe, the others ranging across sci-fi possibilities, from a kind of horror story to one about a failing Russian space station

1986 Count Zero by William Gibson – second in the ‘Sprawl trilogy’

1987 2061: Odyssey Three by Arthur C. Clarke – Spaceship Galaxy is hijacked and forced to land on Europa, moon of the former Jupiter, in a ‘thriller’ notable for Clarke’s descriptions of the bizarre landscapes of Halley’s Comet and Europa

1988 Memories of the Space Age Eight short stories spanning the 20 most productive years of Ballard’s career, presented in chronological order and linked by the Ballardian themes of space travel, astronauts and psychosis

1988 Mona Lisa Overdrive by William Gibson – third of Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ trilogy in which street-kid Mona is sold by her pimp to crooks who give her plastic surgery to make her look like global simstim star Angie Marshall, who they plan to kidnap but is herself on a quest to find her missing boyfriend, Bobby Newmark, one-time Count Zero; while the daughter of a Japanese gangster who’s sent her to London for safekeeping is abducted by Molly Millions, a lead character in Neuromancer

1990s

1990 The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling – in an alternative version of history, Victorian inventor Charles Babbage’s design for an early computer, instead of remaining a paper theory, was actually built, drastically changing British society, so that by 1855 it is led by a party of industrialists and scientists who use databases and secret police to keep the population suppressed