This is the UK’s first ever retrospective of the Russian avant-garde artist Natalia Goncharova. It’s huge, bringing together over 160 international loans which rarely travel, including works from Russia’s State Tretyakov Gallery which houses the largest collection of Goncharova’s work.

The exhibition is imaginatively laid out with some lovely rooms, and it certainly gives you a good sense of her range of styles, not only in painting, but in lithographs, fashion and costume design, especially for modern ballet, posters, pamphlets and much more. But it also leaves you with a few nagging questions…

Peasants Picking Apples by Natalia Goncharova (1911) State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Fabric design

Goncharova was born in Russia in 1881. She grew up on her family’s country estates in Tula province, 200 miles from Moscow. Her family were impoverished aristocrats who made their fortune through textiles, in fact the name of Goncharova’s family estate, Polotnianyi Zavod, means ‘cloth factory’. From early childhood, Goncharova witnessed the rhythms the farmers’ lives – working the land, planting and harvesting – and also became deeply familiar with all the stages of textile production, from shearing sheep to weaving, washing and decorating the fabric.

Hence two threads to her artistic practice:

- fabric design, which ran through the 1910s and led to her wonderful designs for the Ballets Russes in the 1920s and 30s, as well as commissions from fashion houses

- a profound feel for the rhythms of agricultural labour, which she depicted in a number of early paintings (like Peasants picking apples, above)

The first room epitomises both threads with several paintings showing agricultural labourers, in a highly modernist style, alongside a display case containing an example of the kind of traditional costume worn by the peasant women on Goncharova’s estate.

Cubo-futurism

What comes over is Goncharova’s very quick artistic development from about 1908, when she was doing stylised but essentially traditional paintings of peasant subjects, to 1911 when she had transformed herself into one of the leading lights of the Moscow avant-garde.

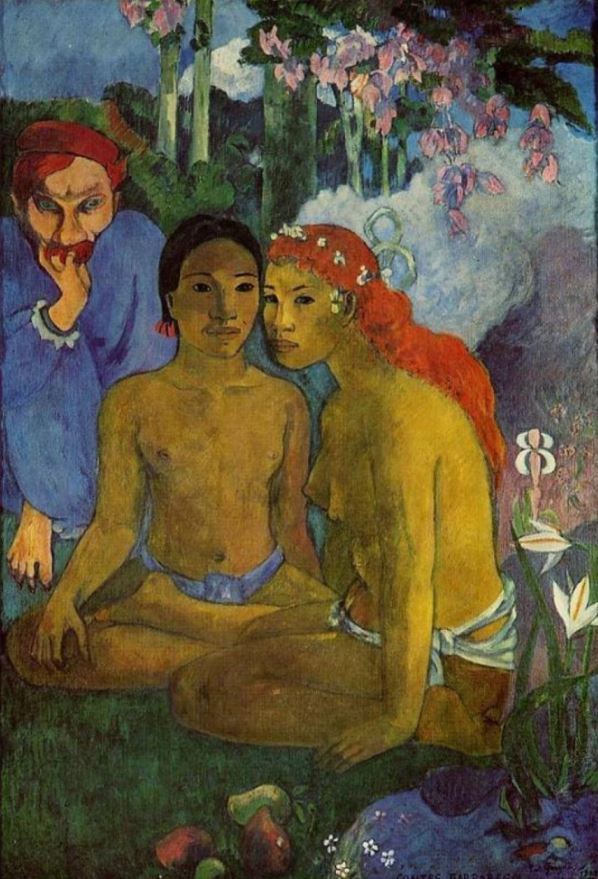

Her swift development was helped by two Moscow industrialists – Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin – who had built up extensive art collections of leading European artists such as Cézanne, Gauguin, Picasso and Derain, and made their collections accessible to the public. These French works had an electrifying effect on young Russian avant-garde artists, which was accentuated by news of the new movement of Italian Futurism, which they could read about in international art magazines.

Goncharova swallowed both influences whole and became the leader of what contemporaries came to call Russian ‘cubo-futurism’. Various contemporaries are quoted commenting that she was the leader of the younger generation, not only in painting, but in self-presentation, creating an avant-garde ‘look’, as well as happenings, given walking through Moscow’s streets wearing stylised tribal markings on her face, or involved in volumes of avant-garde poetry published just before the Great War.

A work like Linen from 1913 seems to be a straight copy of Picasso-style cubism, cutting up an everyday domestic scene into fragments and pasting in some text, as if from a newspaper or advertising hoarding. The main differences from a cubist work by Picasso or Braques is that the text is in Russian, and the bright blue is completely unlike the cubist palette of browns and greys.

The 1913 exhibition and ‘everythingism’

This exhibition feels logical and well designed, and features at least two particularly striking rooms. The first one is dedicated to recreating the landmark retrospective Goncharova was given in September 1913 at the Mikhailova Art Salon in Moscow. The 19193 show included more than 800 works (!) and was the most ambitious exhibition given to any Russian avant-garde artist up to that date. Goncharova was thirty-two years old.

The curators have brought together thirty big paintings which featured in the 1913 show and created a central column in the style of those circular bulletin boards you get in Paris, on which they have plastered copies of some of the posters and reviews of the original exhibition.

Here we learn that Goncharova’s fellow artist and long-time partner, Mikhail Larionov, invented the term ‘everythingism’ to describe her openness to diverse styles and sources, the way her paintings invoke all kinds of sources from the folk designs of her family farm, through to the latest ideas from Paris and Rome.

Thus the thing which comes over from the 30 or so works in this room is their tremendous diversity. There’s a striking female nude which reminded me of something similar by Matisse, there’s a pipe smoker at a table, a motif familiar from Cézanne, there’s a surprising work which looks like a dappled impressionist painting. It really is a little bit of everything and so ‘everythingism’ seems an accurate label.

You could claim this is as a positive achievement, indeed one of the wall labels praised the lack of ‘hierarchy’ in Goncharova’s diverse styles and I understood what they were getting at. There was the implication that it is somehow masculine to want to be the leader of the avant-garde, at the cutting edge, always one step ahead: and somehow a slave of capitalist or consumer culture to need to create a unique brand or style.

By contrast, Goncharova is praised for her more easygoing, unmasculine and uncapitalist stance – allowing herself to be open and receptive to all kinds of visual approaches, mixing Cézanne with Russian icons, or cubism with peasant designs, or futurism as applied to distinctly Russian cityscapes. She was presented as ‘a universal artist’.

You can see how, at the time, she seemed to contemporaries to be a one-woman explosion of all the latest visual breakthroughs and trends because she was covering so much territory.

The drawback of this approach is that Goncharova risks, in retrospect, appearing to be a Jill of all trades but a mistress of none. Lots of the works in this room were interesting but you found yourself thinking, ah, that’s the cubist influence, that’s the futurism, that’s a touch of Cézanne, and so on. They all had her mark, but not so many seemed entirely her, if that makes sense.

For me the most distinctive work in the room was the series of paintings she called Harvest, which was originally made up of nine large works which were designed to be hung together. Two have gone missing but Tate have hung the other seven together on one wall and the effect is stunning.

Harvest: Angels Throwing Stones on the City (1911) by Natalia Goncharova. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

The palette of red, orange and tan runs across all seven paintings and gives them a tremendous visual unity. Also note the highly stylised, almost child-like depiction of the human figure, with simplified arms and legs and big simple eyes. The same big wide white eyes with huge jet black irises which appear in Peasants picking apples. This is maybe her core visual style.

Harvest uses Christian motifs. It was inspired by popular prints and the frescoes in Russian cathedrals and takes its images from the Book of Revelation in which the end of the world is presented as a symbolic harvest with the grapes of human souls being gathered and thrown into the winepress of God’s anger.

All in all, surprisingly religious, unironically religious, for an avant-garde artist. It comes as no surprise to discover that room six of the exhibition is devoted to just her religious paintings, featuring half a dozen enormous works she did on Christian subjects, notably four tall narrow full-length portraits of the four evangelists. I can see the way she has applied her distinctive cubo-futurist style to a very traditional Russian subject – I note her characteristic way with big white eyes – but I didn’t really warm to them.

Fashion and design

Room four picks up the theme of Goncharova the fashion designer, showing work commissioned from her by the couturier to the Imperial court, Nadezhda Lamanova, in 1911 to 1912. This room also includes work commissioned from Goncharova after the war by Marie Cuttoli, whose design house Myrbor showcased carpets and fashion designs by famous contemporary artists.

There’s a series of sketches from the 1920s, haute couture-style sketches which make the women subjects look as tubular as a Fairy Liquid bottle, with no hips or waist or bust, which were utterly unlike her modernist paintings, and looked more or less like any other fashion sketches for stick-thin flappers from the Jazz Age.

But on the opposite wall was a piece which I thought might be my favourite from the whole show, a study Goncharova did for a textile design in the later 1920s. I loved the vibrancy of the colours and the primitiveness of the design. In fact it’s only one of a series she did using bird motifs but, to me, it was a standout piece.

Design with birds and flowers: Study for textile design for House of Myrbor 1925 to 1928 by Natalia Goncharova. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

The Great War

In April 1914, Goncharova and Larionov were invited to Paris by the famous ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev to work on designs for his opera-ballet The Golden Cockerel. This was presented in Paris to great acclaim and the pair followed it up with an exhibition. But then the Great War broke out, and both were forced to return to Moscow. Larionov was called up for military service and sent to the front line, was wounded within weeks and invalided out of the army.

Goncharova responded to the crisis by creating a series of prints titled Mystical Images of War which brought together symbols Britain, France and Russia together with images from the Book of Revelation and Russian medieval verse. They use her trademark stylisation of the human face and eyes, and throw in the religious iconography which we’ve by now realised was a big part of her psyche.

The fourteen or so prints on display in room five are a really interesting mix of modern warfare and traditional Orthodox iconography, featuring angels wrestling biplanes, the Virgin Mary mourning fallen soldiers, and the Pale Horse from the Apocalypse. She chose to create prints in order to reach a broad popular audience with what are, essentially, patriotic rallying cries, which also feature patriotic heroes who defended Mother Russia against invaders.

‘Angels and Aeroplanes’ from Mystical Images of War by Natalia Goncharova (1914) © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Books and photos

Room seven is a narrow corridor between the conventionally-shaped rooms six and eight. As in other exhibitions, this corridor makes a good space not to hang works of art, but to place books, pamphlets, photos, prints and posters related to the artist under review, in the long rack of display cases lining the wall.

For this exhibition the curators have displayed artist manifestos, exhibition catalogues and a number of books of poetry which Goncharova was involved in writing or designing or illustrating. The later part of the case displays the ephemera she produced for a series of artists’ balls in Paris, including posters, tickets and programmes. There’s a speaker on the wall from which comes a Russian voice reciting some of the avant-garde poetry included in the pamphlets on display. (It is, apparently zaum or ‘transrational’ poetry, from ‘World Backwards’ by Alexey Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov, and Vzorval or ‘Explodity’ also by Kruchenykh.)

Cubo-futurism

Room eight is devoted to another series of cubo-futurist works, highlighting classic Modernist-style depictions of factories and machines and cars and bicycles, all those implements of power and speed which were fetishised by the Italian founder of Futurism, Marinetti.

There are some great pieces here, classic Futurist depictions of machines and factories, a big painting of a bicyclist, another titled Aeroplane over a Train, and a vivid depiction of rowers on the river (which reminded me of the similar treatment given the same subject by Cyril Powers, the British printmaker, twenty years later, as featured in the current exhibition of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art at Dulwich Picture Gallery).

Cyclist (1913) by Natalia Goncharova (1881 to 1962) State Russian Museum © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Admirable though many of these paintings were, I began to be nagged or puzzled by something. Usually in a major retrospective, you are shown samples of the artist’s work throughout their career. Goncharova was established as a leader of the Russian avant-garde by the time of her huge exhibition in 1913, and lived on until 1962, producing works well into the 1950s.

So where are they? Where are all the later works? Here we are in room eight of ten and we are still… only at 1913?

The first eight rooms of this ten-room survey have all hovered around the years 1910 to 1914. Nowhere does the exhibition say so explicitly, but are we to conclude from this lack of later content that her golden years were a brilliant but brief period, from 1911 to 1914 or 1915?

Goncharova in Paris

Only in this, the ninth and penultimate room, do we learn what happened to Goncharova as a result of the Russian Revolution, namely that she and Larionov were on a tour with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes through Switzerland, Italy and Spain when the October Revolution broke out. The revolution, and then the civil war, prevented them from returning home, and in 1919 Goncharova moved into a flat in Paris that would remain her home for the rest of her life.

This penultimate room contains half a dozen works from the 1920s during which Goncharova received more commissions for ballet costume, some from fashion houses (as mentioned earlier) and a few funky commissions for interior design, including an impressive painted screen made in 1928 for the American patron Rue Winterbotham Carpenter. She did the interior designs for the Paris house of Serge Koussevitsky, exploring the motif of the Spanish Lady on a monumental scale.

When she had accompanied the Ballet Russe in Spain, Goncharova had become fascinated by the clothes of the Spanish women she saw, and ‘the Spanish woman’ became a recurring motif in her inter-war years, maybe because the vividness and ethnic distinctiveness of the outfits reminded her of the Russian peasant look she knew so well.

By far the most impressive work was a huge abstract work titled Bathers from 1922. It is immense, at least fifteen feet across, and reminded me of all kinds of other modernist abstract painters though I couldn’t quite put my fingers on who. First time it’s ever been exhibited in the UK and a coup for the exhibition organisers.

Ballet designs

Anyway, the point remains – why isn’t there more of her work from the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s? You might have expected the last room in the show to cover the later part of her career but, instead, the exhibition takes an unexpected detour to make this final room, arguably the best in the exhibition.

It is a big space which has been specially darkened to create an atmospheric setting in which to review Goncharova’s work for the ballet and the theatre. Lining the walls are drawings and sketches for costumes Goncharova designed for productions of The Golden Cockerel (Rimsky-Korsakoff) and Les Noces (Stravinsky). There are some videos of her costumes and backdrops being used in revivals of the ballets, The Golden Cockerel footage is a silent but colour film of a production dressed in Goncharova’s costumes which toured Australia in the late 1930s.

But the highlights of the room are four or five of the actual costumes themselves, the costumes Goncharova designed for these classic ballet productions, which are featured in display cases around the room. They are all wonderfully bright and imaginative, drawing on the (to us) exotic and fanciful traditions of Russian legend and folklore.

Theatre costume for Sadko (1916) by Natalia Goncharova. Victoria and Albert Museum, London © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

And, last but not least, the room is filled with music, with clips from the famous ballet scores in question, wonderful Russian melodies filling the air as you stroll from wonderful costume to fascinating set designs, or stop to watch footage of actual performances using Goncharova’s colourful and vivid costumes.

The music, the darkened atmosphere, the videos of performances, and the glass cases of costumes – all make this room completely unlike the previous nine and a very evocative space to be in.

Summary

This is a major exhibition by a leading Russian artist who, for a period before the Great War, epitomised the avant-garde for her compatriots. She produced a lot of striking paintings, as well as pioneering designs for ballet costumes and sets, and a wealth of prints and posters and pamphlets and poetry books.

And yet I was left with two nagging questions: first, from such a profusion of images and designs, not that much really rang my bell. A lot of it was striking and thought-provoking and interesting – but possibly only the design with birds and flowers really set me alight.

The stylised human figures with those big eyes is the nearest Goncharova comes to having a recognisable ‘look’ and I liked it, but only up to a point. I actively disliked its application to the icons and evangelists and wasn’t, at the end of the day, that taken with the Great War prints, either.

Comparison with Käthe Kollwitz

Great War prints by a woman artist made me think of the epic prints created by the German woman artist Käthe Kollwitz. These are infinitely more powerful. Comparing the two made me think that maybe Goncharova was held back by her attachment to the Russian Orthodox tradition and its Christian iconography. Kollwitz, by contrast, has broken free of all traditional or religious straitjackets in order to create spartan images of humanity under stress which still speak to us today with horrifying force.

Then again, maybe I’m comparing apples and oranges. Goncharova’s works were created at the very start of the war, when it was thought of as a religious crusade, and everyone thought it would be over by Christmas. Whereas Kollwitz’s haunting images were made nearly ten years later after not only bitter defeat, but collapse of the German state and descent into semi-civil war. So it’s not a fair comparison at all. But you can see why, if you set the two side by side – as we latecomers a hundred years later are able to – Kollwitz’s images are vital, a necessary record of a horrifying period; whereas Goncharova’s are an interesting and nice inclusion in a retrospective of her work, but have nowhere near the same importance or force.

Where is the later work?

And second, where was the work from the later years? Are we to deduce from its almost complete absence from this exhibition, that the curators consider Goncharova’s work from the 1930s, 40s and 50s to be poor or sub-standard? Or is it for some reason hard to borrow and assemble for an exhibition like this?

As far as I could see, the only work dating from either the 1940s or 1950s was one medium-size set design for Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird, which Goncharova drew in 1954.

Set design for the final scene of The Firebird by Natalia Goncharova (1954) Victoria and Albert Museum, London © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

I thought this was brilliant, vivid and fun, in a completely different style from everything which preceded it, like a highly stylised illustration for a children’s book. So is this what Goncharova’s work from the 1950s looked like?

Having devoted eight or so rooms to going over with a fine tooth comb the intricacies of her output from 1911 to 1915 or so, it’s a shame we didn’t get at least one room telling us what happened to her style in the entire last thirty years of her career.

Video

‘Visiting London Guide’ produce handy two-minute video surveys of all London’s major exhibitions. I include them in my blog because they give you an immediate sense of what the exhibition looks like.

Related links

- Natalia Goncharova continues at Tate Modern until 8 September 2019