This exhibition in is in the smaller set of three rooms at the back of the Royal Academy building i.e. it’s more of an amiable stroll through three rooms of relatively small drawings, rather than, say, the full-on assault course of the 11 big rooms of the extraordinary Marina Abramović show.

It does what it says on the tin, brings together 80 or so works by all the famous Impressionist and post-Impressionist artists plus quite a few I’d never heard of before, experimenting with different media on paper.

Exhibitions need an aim or project and this one aims to explore how Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists in late 19th-century France didn’t just use paper works as studies but radically transformed the status of works on paper. Previously, drawings were mostly conceived as preparations for paintings; in the hands of the Impressionists drawings, pastels, watercolours, temperas and gouaches were increasingly perceived as more than just preparatory techniques, and became autonomous works of art, claiming a shared aesthetic with painting.

Dancer Seen from Behind by Edgar Degas (c. 1873). Essence (diluted oil paint) on prepared pink paper. Collection of David Lachenmann

Who are we talking about? The eye-catching famous artists are: Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Eva Gonzalès, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh.

Less well known are the likes of Albert Lebourg, Jacques Emile-Blanche, Armand Guillaumin, Frederico Zandemeneghi.

Impressionists recap

As the curators explain:

The avant-garde artists known as the Impressionists came to prominence during the late 1860s and early 1870s, first exhibiting in Paris as a group in 1874. They shared a concern to depict scenes from everyday life and to address contemporary issues, which encouraged them to challenge traditional attitudes to drawing and seek innovation. Vivid colour, a quick, loose touch, and daring viewpoints, together with a deliberate lack of finish, were their means of capturing the fugitive effects of nature as well as vignettes of modern life.

The portability of drawing materials greatly facilitated direct observation and the recording of scenes on the spot. The eight Impressionist exhibitions, held in Paris between 1874 and 1886, included a large number of works on paper and reflected their shift in status. This was also encouraged by dealers who recognised the economic advantage of exhibiting and selling works on paper.

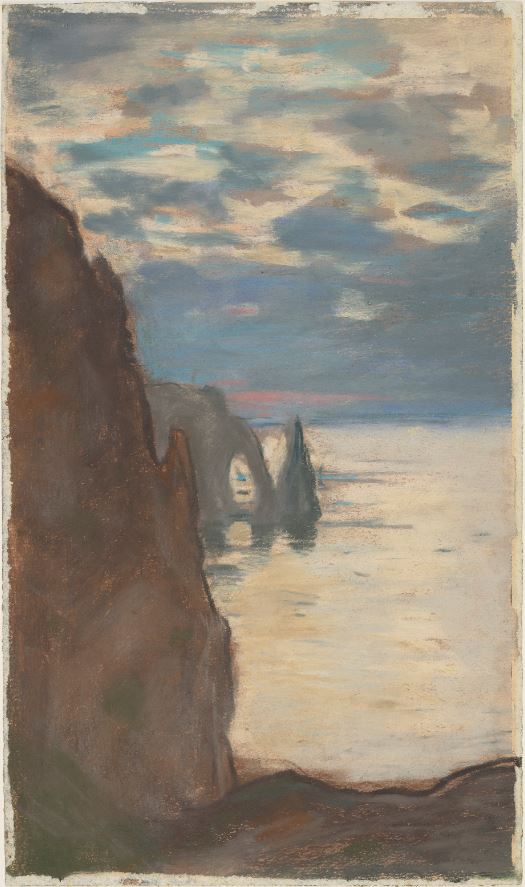

Cliffs at Etretat: The Needle Rock and Porte d’Aval by Claude Monet (c. 1885). Pastel on wove paper. National Galleries of Scotland

What it’s like

The most striking thing, for me, was how the drawings faithfully echo the style of each artist’s paintings i.e. the way each of the artists have strong signature styles or vision no matter what medium they’re working in.

So you see a hazy landscape of cliffs by the sea and instantly know it’s Monet; charcoal images of ballet dancers posed at striking angles and know its Degas; a round-faced woman’s face smiling at some outdoors dance and know it’s Renoir; a grotesque, angular woman in an urban setting and you know it’s Toulouse-Lautrec; a light and airy landscape made out of cubes and rectangles of colour and you know it’s Cezanne.

So you can play an entertaining game of standing far away from the wall to try and identify the artist by their style, then stroll over to the wall label to find out if you were correct. For example, who would you think this is by?

Portrait de Marie-Thérèse Gaillard by Mary Cassatt (1894) Pastel on paper. Private collection. Photo © 2007 Christie’s Images Limited

In this case it’s a trick question. You might have thought Renoir, from the treatment of the face, but it is in fact by Mary Cassatt. Note the striking difference in finish between the face – expertly and completely rendered – and the clothes, rendered in a completely different, hurried, unfinished style, with the background wall hovering somewhere between the two.

What I liked

The most striking work in room 1 is the Portrait of Madame Henri Wallet by Jacques Emile-Blanche simply because of its size. It’s a John Singer Sargent-style and sized portrait of an elegant society woman, and so stands out in a room full of much smaller, much more hazy and impressionistic images.

Degas sketched and drew things around him so compulsively that his colleagues nicknamed him Monsieur Pencil and, appropriately, there are more works by him in this exhibition than any other artists, 12 in total, all of which I liked.

I love sketches and drawings, I love art which is half-finished, ghostly, hinting at a half-grasped reality, which is why I’ve always loved Degas’ strange and mysterious Woman at a Window (1871), which used to be tucked away in a side room at the Courtauld Gallery. Here it is presented in all its pregnant mystery and an epitome, for me, of the power of paintings or drawings which are better left unfinished, full of hints and implication.

But I’d forgotten, if I ever knew, about Degas’s friend Frederico Zandemeneghi (1841 to 1917). Zandemeneghi was invited by the Impressionists to exhibit at four of their 8 exhibitions. He was particularly close to Degas. They shared an interest in depicting scenes of modern life featuring women subjects, seen from unconventional viewpoints, often cropping the image unexpectedly, and using vibrant colourful pastels.

This example has several of those characteristics in spades, namely the dramatic cropping which makes the subject feel really close-up and in your face. And the very bright colours, blue, yellow, orange, red, making the most of the range of human sight.

Study of a Woman from Behind by Federico Zandomeneghi (1890 to 1897) Pastel on cardboard. Galleria D’Arte Moderna, Milan. Photo © Comune di Milano

The show is in chronological order, starting with works from the 1870s. Room 2 contains works from the 1880s. The highlight for me was van Gogh’s ‘The Fortifications of Paris with Houses’ from 1887, made from a combination of graphite, chalk, watercolour and gouache. This reproduction in no way conveys the glowing brightness of the original. Then I liked the contrast between the architecturally accurate apartment block on the left and the vague ‘impressionistic’ grass in the foreground. Then I noticed the way the big fortification wall is not made of bricks but of hundreds of vertical dabs of orange and grey. And then I noticed the ghostly couple walking past in the foreground, ghosts of the millions of people who lived and died in the great cities of Europe, leaving barely a trace of chalk on paper. At which point I realised that there’s a kind of spectrum of solidity, from the super-solid apartment blocks on the right, to the more dabbed and impressioned fortifications themselves, and then to the human beings, the least permanent or impactful things in the picture or in history, hundreds of millions of us leaving less trace than walls or buildings.

The Fortifications of Paris with Houses by Vincent van Gogh (1887) Graphite, black chalk, watercolour and gouache on paper. The Whitworth, The University of Manchester. Photo by Michael Pollard

The exhibition concludes in room 3 with works from the 1890s and 1900s, which saw an ever-growing appreciation of works on paper and a proliferation of exhibitions of the medium. There’s a lot more Degas who emerges as probably the strongest and most consistent artist on paper. Off in one corner is a set of quiet, thoughtful, washed-out watercolours by Cézanne from late in his career. At the opposite corner of the room, both literally but also in terms of subject matter is a small set of three vivid, scratchy, angular images of the louche underworld of Montmartre by Toulouse-Lautrec.

But floating above this world of human troubles is the work I liked the best, a classic of what, during the 1890s came to be known as Symbolist art, the wonderful, visionary ‘Ophelia among the flowers’ by Odilon Redon.

The Impressionists were trying to capture the truths of the modern world, applying light quick touches to capture the fleeting moment. Redon, by complete contrast, sought out ‘the light that never was on land or sea’, depicting images from the inner world of fantasy and dream. So I thought he was pretty out of place in an exhibition of impressionists. But his inclusion makes sense if we forget the exhibition’s main title for a moment and think of it more as a study of the evolution of drawing and painting on paper in France from the 1870s to the 1900s. From that perspective the inclusion of Redon makes sense for his technical prowess. The flowers are obviously the dominant element in the work, but after a while you realise that it’s the peculiar quality of the light in the top middle and right of the image which give it its haunting, apocalyptic quality.

Consequences

According to the curators:

The French avant-garde artists’ interest in drawing and the remarkable range of their production had far-reaching consequences. The hierarchical distinction made between painting and drawing ceased to exist. Freedom of execution and a laissez-faire attitude to materials provided an impetus that allowed the world to be depicted in more imaginative ways, leading to developments in 20th-century art such as Abstract Expressionism.

So as we progress through the works in chronological order, we are not just witnessing the development of visual styles, generally away from figurativism and towards greater abstraction, but the evolution of the medium of drawing itself, as it prepares for the great lift-off of modern art at the start of the twentieth century.

It’s not all masterpieces. Some are not-great early works (for example, by van Gogh or Gauguin) which are of largely scholarly interest, others are wishy-washy landscapes which are a bit meh (Armand Guillaumin). But overall it’s a lovely civilised way to spend an hour, enlivened by a regular stream of masterpieces. It’s worth visiting just to see the 12 Degas works and the 3 or 4 pieces by Frederico Zandemeneghi and the van Gogh. But other visitors will find other works to marvel at and cherish.

Dancers on a Bench by Edgar Degas (around 1898) Pastel on tracing paper © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Related links

- Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec continues at the Royal Academy until 10 March 2024