This big heavy paperback is the glossy catalogue to a comprehensive exhibition of Grosz’s work which was held in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection back in 1997. The long and detailed text was written by Ralph Jentsch, who is ‘managing director of the Grosz Estate, author of a number of catalogues and books on George Grosz, and a well-known expert in German Expressionism.’

It is a massive compendium of works by Grosz in all media – cartoons, caricatures, book illustrations, oil paintings, watercolours, sketches, drawings, collages and so on, not just from his mature years but starting with his earliest surviving sketches of cowboys and Indians and the heroes of boys’ own adventure stories which he loved as a lad.

There’s also plenty of evocative black-and-white photos of Grosz during the first 40 years of his life (1893 to 1933), featuring lots of semi-private shots of him messing about in his studio or playing the banjo – and also photos which give context to the story, from a typical German pub interior of the 1890s of the sort his father ran, to street scenes in Berlin, where he made the first half of his career.

In total there are 410 numbered works and photos in the main text, plus an additional 67 b&w photos in the 16-page potted biography at the end. It’s a visual feast, as they say, giving you a real sense of the visual universe he inhabited and the one he created.

(This book is the first volume of a two-volume and two-exhibition project – this one covers the Berlin years, the second one covers his time in exile in America, 1933-1959. Later, they were combined into one portmanteau book, link below.)

I’ve summarised Grosz’s life story in my review of his autobiography, A Small Yes and a Big No, no need to do it again. Instead, I’ll just mention half a dozen or so themes, issues or ideas which arise from a careful reading of this big book.

Transition from soft to hard lines

The first thirty or so pages include still life sketches Grosz did in conventional pencil or charcoal using multiple lines and hatching to create light and shade. These go alongside a consciously different style he developed for commercial caricatures, still very formal and multi-lined with an Art Nouveau feel. He had a different style again for the pictures he was hoping to use to start a career as a book designer.

Among the multitude of early sketches there are pub scenes, brawls in the street, and some gruesome (imaginary) murders. The point is – they’re all done in a much scribbled over, blurry, multi-line style.

What’s fascinating is to see how, during the war, he quickly and decisively changed his style to one of spare, scratchy single lines. Stylistically, it’s the decisive move: before – smudgy, obscure, feverishly drawn and overdrawn figures; after – scratchy, one-line figures, buildings, objects.

Evening in Motzstraße (1918)

It’s fascinating to read his own account of how and why the change came about.

In order to attain a style that reproduced the hardness and insensitivity of my subjects, I studied the most direct expressions of art: I copied the folkloristic drawings in the urinals; they seemed to me the expression and most immediate rendering of strong emotions. I was also stimulated by the unequivocalness of children’s drawings. So I gradually reached my knife-hard style that I needed to draw what I saw. (Art in Danger, 1925)

I wonder if any other major artists, anywhere, ever, has credited their style as being derived from the drawings in public lavatories?

This is just one revealing quote from the many which Jentsch gives us from Grosz’s own autobiography, from the prefaces to the books, to the justificatory notes he prepared for each of his court cases, and to the countless letters he wrote to all his friends. We learn that Grosz wrote a vast correspondence to all his friends and acquaintances, kept copies of it all (which survive) and expected long and detailed replies in return – or else the friends were liable to get a none-too-polite reminder.

Grosz is a really fluent and enjoyable prose writer – his descriptions of holidays on the Baltic or the threatening atmosphere of Depression Berlin are a joy to read in their own right.

America

Jentsch’s quotes very liberally from Grosz’s autobiography (it is, after all, extremely jocular and readable) in bringing out Grosz’s obsession with America and its pop culture. As a boy he devoured James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking novels, as well as the pulp westerns of Karl May, the detective hero Nick Carter, and loved everything American.

Having just read John Willett’s two books about Weimar art and culture, I can see that Grosz’s enthusiasm was part of a much broader cultural trend: the Germans loved American culture. Not only was there jazz which took everyone by storm, but the radio and gramophone were American inventions and everyone round the world fell in love with Charlie Chaplin’s silent comedies.

Later, for the avant-garde designers and architects which Willett’s book describes, America remained the beacon of all things modern, particularly the staggering efficiency of its industry and design. Henry Ford’s many books were bestsellers in Germany, as were the innovations of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s time and motion and efficiency studies.

I always think the most incongruous fan of America in this milieu was the Marxist playwright Brecht, who wrote loads of poems about a fantasy America, devoted a play to Chicago gangsters, as well as setting a number of plays and oratorios there, such as his oratorio about Lindbergh’s famous solo flight across the Atlantic. American jazz, cars, fashions and technology all stood for the exciting and new, liberated from the dead hand of Old Europe and its defunct empires.

Towards the end of his Weimar career (and in the depths of the Great Depression) Grosz’s attitude towards America (like Brecht’s) had become a good deal more satirical and critical. Now he sees all mankind as blindly greedily chasing after the consumer capitalism which America has perfected and exported to the world. But although the attitude has hardened – it’s still America which is at the centre of his thoughts.

Dreams, romantically dispensed and advertised a thousand times over: comfortable living, bath-tub, sports, utility car, and at best a weekend with cocktails and beauty queen. America has shown the way, we’re following after – due to war somewhat behind – in our naturally slow way. Even in Marxist Russia, America is the model and ardently desired goal. The goal is: rational exploitation of all raw material sources so as to procure comfort for the little man on the basis of mass machine production. (quoted page 135)

Just one year later – 1933 – Grosz was himself in America, beginning the long struggle to make a new career, which is described in his autobiography and in the second of these two volumes.

Alas, several of Grosz’s biggest most colourful fantasias on American themes (from the end of the Great War and featuring cowboys with six-shooters, wizened old trappers, gold miners and saloon whores) were confiscated by the Nazis and have never been found, so we only know them from old photos.

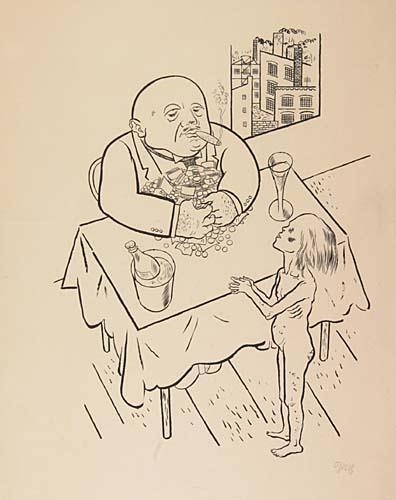

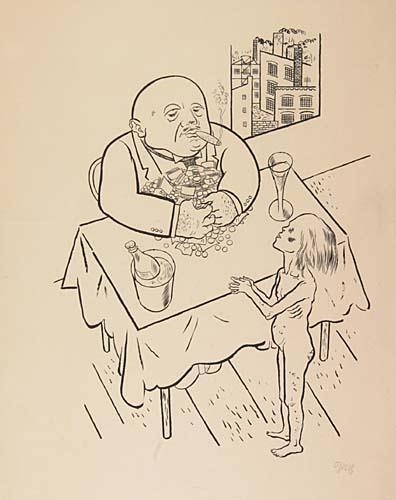

Misanthropy

Boy, Grosz hated people, he always hated people, he really hated people. Jentsch’s book clarifies that Grosz never saw action during the Great War, he had a nervous breakdown before he reached the front and ended up back in Berlin making sketches, caricatures and paintings which expressed his virulent hatred for people, for men, and for Germany in particular, for the state which had committed its young men to this suicidal folly and which had wanted to force him into the meat grinder.

It was a combination of loathing Germany and obsessing about America which made him change his name from the original Georg Groβ to the Anglicised George Grosz (just as his close friend and collaborator Helmut Herzfeld changed his name to the Anglicised John Heartfield).

Grosz’s misanthropy makes a mockery of his so-called communist beliefs. He joined the German communist party the day it was set up in November 1918 and played a role in the 1918 Berlin revolution, signing a revolutionary declaration published by a collective of revolutionary artists. But after his trip to the USSR in 1922 (where he actually met Lenin), Grosz quickly lost any political faith and lapsed into a universal contempt for mankind.

Hatred for humanity drips from the hundreds and hundreds of drawings from this era, and from the watercolours in particular, which show a relentless parade of corrupt and ugly old men, apparently surrounded by grim, half-naked prostitutes.

Before sunrise (1922)

As Grosz wrote to his friend J. B. Neuman:

My drawings will naturally stay true – they are fireproof. They will later be seen as Goya’s work [is]. They are not documents of the class struggle, but eternally living documents of human stupidity and brutality.

Red

In 1916 to 1918 Grosz went through a red phase, lots of paintings done almost entirely in shades of blazing red. The house is on fire, the city is going up in flames. It didn’t last too long, but while it did it was very, very red.

Metropolis (1917)

A painting like this displays a raft of his characteristics. The knife-hard outline styling of all the figures is well established. Humans are caricatures with hardly any attempt at naturalistic shading or modelling. Perspective has been thrown away in preference for a crazy vortex of planes which gives the sense of a crashing chaos of urban architecture. Women are more often than not half or completely naked, with a little pubic bush in sight just to ram home the point. Corruption, sex, seediness. Everywhere.

Nudes

Grosz did a surprising number of nude studies, almost all of them unflattering or verging on the grotesque.

More surprisingly, he did a large amount of pornographic sketches and drawings, pornographic in the sense that they show men and women very explicitly and enthusiastically engaging in sexual practices, his misanthropy coming over loud and clear in the fat ugliness of everyone involved.

But there’s also something haunted about portraying men and women again and again at the feverish, pleasure-filled but somehow empty, tragic and futile copulations which obsess humanity, and to what end.

The obsessive reworking of the same theme (he liked women bending over and displaying their big wobbly buttocks) give the sense of a man questing, searching, trying to find the answer to the reason – why? Why are we animals? Why do we behave like farmyard beasts? What is behind this absurd farce?

The sex drawings cross over with a set of disturbing sketches and paintings of a cartoon character called ‘John the slayer of women’, who was much in his thoughts in 1917 and 1918. He claimed the set was inspired by a notorious murder of the time – or was it just a misogynist way to let off steam and vent the huge amount of anger he had permanently burning inside?

John, The Lady Killer (1918)

Dada and collage

Grosz was a central figure in the Berlin branch of Dada which got going about 1918. He formed a close working partnership with the Herzfeld brothers who set up a publishing house for avant-garde work – the Malik-Verlag – where Grosz was able to publish a series of ‘albums’ of lithographs throughout the 1920s (nearly all of which were confiscated and banned by the authorities).

He collaborated with Helmut Herzfeld aka John Heartfield in the invention and development of photo-montage i.e. cutting out objective pictorial elements like photos or text or headlines from newspapers or magazines and pasting them into grotesque and satirical combinations.

Grosz considered the painting below as one of his most important, and it had pride of place at the Dada exhibition in June 1920.

You can see the way any idea of perspective has been completely abandoned in the name of a potentially endless collage of objects, images and planes. The collage element of newspaper cuttings and magazine images is made particularly obvious on the table. There is the characteristically bitter satire of the so-called ‘pillars’ of the establishment at the bottom. And there is a naked woman with boobs and the characteristic hint of pubic hair to the left of the main figure.

Apart from anything else, there’s a ‘Where’s Wally’ pleasure to be had in deciphering all the visual elements in these, the most cluttered works of his career.

Germany: A Winter’s Tale (1918)

Watercolours

Grosz had a number of styles – or a number of ways of deploying his basic vision. Thus the book juxtaposes the intense oil paintings (above) with the just as savage watercolours, but the latter have a very different feel. Watercolour makes the images lighter and Grosz has a very stylish way of letting the colour leach and bleed around the central subjects, something not possible in oils.

Waltz dream (1918)

The nipples and bush of a scantily-clad woman/prostitute are probably the most prominent visual element, but what I like is the variety and inventiveness of the colours and the way they are arranged in patches or facets. Surprisingly decorative, isn’t it?

De Chirico vistas and mannequins

In 1919 and 1920 Grosz experimented with a series of works which combined receding vistas of perfect multi-story buildings, as developed by the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, with the photo-montage technique he’d been developing with Heartfield.

The result is uncanny, weird and grotesque objects made out of material cut from newspapers and magazines. The final, unsettling element is the omission of faces from the human figures, their heads instead the blank ovals of the shop-window mannequins of the day.

Republican Automatons (1920)

In a completely different style from the raging, red fractured cityscapes, here Grosz presents man as a faceless robot, a characterless shop-window dummy in a soulless landscape of factories and houses, a heartless automaton made up of interchangeable parts (as Jentsch puts it, on page 122).

To ram the message home Grosz stopped signing these automaton paintings and had a stamp made which said GEORGE GROSZ CONSTRUIERT, emphasising their machine-like quality.

Portfolios and collections

Drawing can be an effective weapon against the brutal Middle Ages and stupidity of man of our time, provided that the hand is trained and the will is clear.

As early as 1916 Grosz had a plan for a vast three-volume collection of drawings to be titled The Ugliness of the Germans. In the event he managed to get published the First George Grosz Portfolio and The Little George Grosz Portfolio in small editions. As you can imagine, original copies of these are worth a fortune today.

One of the great virtues of Jentsch’s book is that it includes nearly all the drawings from all his major collections, including the later ones which caused such a scandal – Gott mit uns (1920), In the shade (1921), The Brigands (1922), Ecce Homo (1923), The Mirror of the Bourgeoisie (1925) The New Face of the Ruling Class (1930).

This allows you to see what all the fuss was about and judge for yourself. It also lets you see each of the series in the context of the others, building up a cumulative effect.

Jentsch goes into detail about each of the trials, giving dates and places where Grosz and his publishers were arraigned and their punishments on each occasion (fines and confiscations). He devotes quite a few pages to a chronology of one of the longest court cases in the history of the Weimar Republic, the prosecution of Grosz and his publisher Herzfeld for some of the illustrations created for a stage adaptation of the classic novel, The Good Soldier Svejk, which started in 1928 and went through four separate trials on into 1932.

Grosz really was a thorn in the side of respectable society and it’s worth buying the book for the portfolios alone, which in their spare directness brutally convey seething his seething anger at man’s inhumanity to man.

‘Lions and leopards feed their young’ from The Brigands (1922)

Grosz was lucky, very lucky to happen to be offered a job in New York in 1932, and to persuade his wife and children to join him early in 1933, just two weeks before Hitler came to power.

He’d been taking the mickey out of Hitler for over ten years. On the day of Hitler’s accession SA troops broke into both Grosz’s flat and Berlin studio. If he’d been there he would have been taken off for interrogation, torture, prison and probable death. Lucky man.

Siegfried Hitler by George Grosz (1922)

And he was right when he compared himself to Goya. To later ages, to our age, his drawings and paintings are comparable with Goya’s, as ‘eternally living documents of human stupidity and brutality’.

Related link

Related reviews