At Archie Schwert’s party the fifteenth Marquess of Vanburgh, Earl Vanburgh de Brendon, Baron Brendon, Lord of the Five Isles and Hereditary Grand Falconer to the Kingdom of Connaught, said to the eighth Earl of Balcairn, Viscount Erdinge, Baron Cairn of Balcairn, Red Knight of Lancaster, Count of the Holy Roman Empire and Chenonceaux Herald to the Duchy of Aquitaine, ‘Hullo,’ he said. ‘Isn’t this a repulsive party? What are you going to say about it?’ for they were both of them, as it happened, gossip writers for the daily papers.

I tend to prefer older novels to contemporary novels and poetry because they are more unexpected, diverting, free from our narrow and oppressive modern morality and better written. Go any distance into the past and the characters will have better manners and the narrator write a more grammatically correct English than you get nowadays. There will also be old phrases which I dimly remember from my youth which have now vanished, swamped by all-conquering Americanisms. And, sometimes, you just get scenes which are odder and more unexpected than earnest, issue-led modern fiction can allow itself. Thus, at the opening of Evelyn Waugh’s beautifully written, impeccably well mannered, but ultimately devastating 1932 novel, Vile Bodies, we read:

High above his head swung Mrs Melrose Ape’s travel-worn Packard car, bearing the dust of three continents, against the darkening sky, and up the companion-way at the head of her angels strode Mrs Melrose Ape, the woman evangelist.

Not the kind of sentence you read every day.

Crossing the Channel

Vile Bodies opens on a cross-channel ferry packed with an assortment of Waugh-esque eccentrics, including a seen-it-all-before Jesuit priest, Father Rothschild, a loud and brash American woman evangelist, Mrs Melrose Ape, and her flock of young followers; some members of the fashionable ‘Bright Young People’ aka ‘the Younger Set’ (Miles Malpractice, ‘brother of Lord Throbbing’, and the toothsome Agatha Runcible, ‘Viola Chasm’s daughter’); two tittering old ladies named Lady Throbbing and Mrs Blackwater; the recently ousted Prime Minister, The Right Honourable Walter Outrage, M.P.; and a hopeful young novelist Adam Fenwick-Symes, who has been writing a novel in Paris.

Although there are passages of narrative description what becomes quickly obvious is that Waugh is experimenting with the novel form in a number of ways. One is by presenting short snatches of conversation and dialogue between a lot of groups of characters briskly intercut. No narratorial voice gives a setting or description, there is only the barest indication who’s talking, sometimes no indication at all. You’re meant to recognise the speakers by the style and content of what they say. It’s like the portmanteau movies of the 1970s, like a Robert Altman movie, briskly cutting between short scenes of busy dialogue.

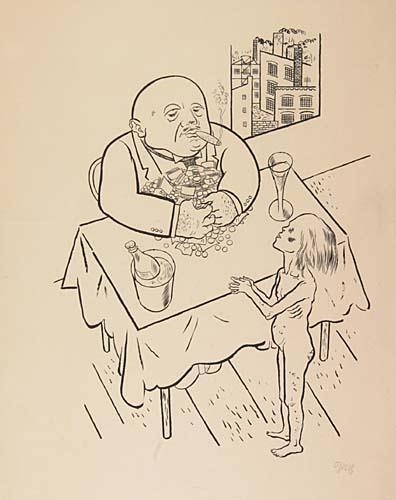

The book as a whole is a concerted satire on the generation of ‘Bright Young Things’, the privileged young British aristocrats and upper-middle-class public schoolboys who were adolescents during the Great War and who graduated from Oxford or Cambridge in the early 1920s, throwing themselves into a lifestyle of wild abandon and endless partying in the rich man’s quarter of London, Mayfair.

As you might expect, we not only get accounts of their activities, but the point of view of their disapproving elders and betters. Here’s the former Prime Minister, who we often find in conclave with Lord Metroland and Father Rothschild:

‘They had a chance after the war that no generation has ever had. There was a whole civilization to be saved and remade — and all they seem to do is to play the fool. Mind you, I’m all in favour of them having a fling. I dare say that Victorian ideas were a bit strait-laced. Saving your cloth, Rothschild, it’s only human nature to run a bit loose when one’s young. But there’s something wanton about these young people to-day.’

The younger generation’s frivolity is exemplified in the way Adam’s engagement with his fiancée, Nina Blount, is on again, off again, on again, their breaking up and making up punctuating the novel right till the end, in a running gag.

To start it off, Adam telephones Nina to tell her that the customs officials at Dover confiscated his novel and burned it for obscenity. She is sad but has to dash off to a party. In London he checks into the eccentric Shepheards Hotel (note the posh spelling), Dover Street, run by the blithely forgetful owner, Lottie Crump, who can never remember anyone’s name (‘”‘You all know Lord Thingummy, don’t you?’ said Lottie”). Lottie was, apparently, based, as Waugh tells us in his preface, on ‘Mrs Rosa Lewis and her Cavendish Hotel’.

Here Adam discovers the posh and eccentric clientele, including the ex-king of Ruritania (my favourite), assembled in the bar (the parlour) and wins a thousand pounds on a silly bet with a fellow guest. So he rushes to phone up Nina to tell her their wedding is back on again. She is happy but has to rush off to a party, as she always does.

Adam goes back to the group of guests, all getting drunk, and an older chap who calls himself ‘the Major’ offers the advice that the best way to invest his money is bet on a horse. In fact, he knows a dead cert, Indian Runner, running in the forthcoming November Handicap at twenty to one. So Adam drunkenly hands over his newly-won thousand pounds to the Major to put on this horse. The reader little suspects that this, also, will become a running gag for the rest of the book.

Then Adam stumbles back to the phone in the hallway and rings up Nina to ask her about this horse. It is a comic premise of the novel that the world it portrays is minuscule and everybody knows everybody else, so it comes as no surprise that Nina just happens to know the horse’s posh owner and tells him it’s an absolute dog and will never win anything. When Adam explains that he’s just handed over his £1,000 to a Major to bet on it, Nina says well, that was foolish but she must dash for dinner and rings off. As usual.

Phone dialogue

A propos Adam and Nina’s conversations, Waugh prided himself that this was the first novel to include extended passages of dialogue carried out on the phone. Something about the phone medium offers the opportunity to make the characters sound even more clipped, superficial and silly than face-to-face conversation would:

‘Oh, I say. Nina, there’s one thing – I don’t think I shall be able to marry you after all.’

‘Oh, Adam, you are a bore. Why not?’

‘They burnt my book.’

‘Beasts. Who did?’

Beasts and beastly. Dreadful bores. Ghastly fellows. I say, old chap. That would be divine, darling. Everyone speaks like that, and focusing on the dialogue brings this out.

Gossip columns and the press

Vile Bodies is wall to wall posh. That was its selling point. Waugh tells us that the ‘Bright Young People’ were a feature in the popular press of the time, as the characters in Made In Chelsea or Love Island might be in ours. Hmm maybe the comparison with a TV show is not quite right. After all, the characters appear in the gossip columns of the papers and some of the characters are themselves part of the set who make a career on the side writing about their friends.

When I was younger there were gossip columns by Taki in the Spectator and Nigel Dempster in the Express and Daily Mail. I imagine the same kind of thing persists today. Obviously people like to read about the goings-on of the rich and privileged with a mixture of mockery and jealousy. That’s very much the mix Waugh was catering to. He’s well aware of it. He overtly describes the ‘kind of vicarious inquisitiveness into the lives of others’ which gossip columns in all ages satisfy.

But over and above the permanent interest in the comings and goings of the very rich, the subject of the dissolute younger generation just happened to be in the news at the time and so Waugh’s novel happened to be addressing a hot topic at just the right moment. He was instantly proclaimed the ‘voice’ of that generation and Vile Bodies was picked up and reviewed, and articles and profiles and interviews were spun off it, and it sold like hot cakes. His reputation was made.

Interesting that right from the start of his writing career, it was deeply involved in the press, in the media. Vile Bodies is, on one level, about the rivalry between two gossip columnists for popular newspapers, and feature scenes in newsrooms and even with the editor of the main paper. Two of his books from the mid-30s describe how he was hired by a newspaper as a temporary foreign correspondent, the two factual books, Remote People and Waugh in Abyssinia. And he used the experiences and material from both books as material for his satirical masterpiece about the press, Scoop (1938). If we look back at Decline and Fall with this in mind, we notice that a number of key moments in that book are caused by newspaper reports, and that many of the events are picked up and reported by and mediated by the Press.

Waugh’s 1930s novels are famous for their bright and often heartlessly comic depiction of the very highest of London high society, but it’s worth pointing out how the topic of the Press runs through all of them, and the extent to which his characters perform their roles and are aware of themselves as performers (see below).

Bright Young People

Anyway, back to Vile Bodies, it is a masterpiece of deliberately brittle superficial satire, the text’s fragmentation into snippets of speech enacting the snippets of apparently random, inconsequent conversation overheard at a party, the world it comes from being one of endless parties, endless frivolity, which he captures quite brilliantly.

‘Who’s that awful-looking woman? I’m sure she’s famous in some way. It’s not Mrs Melrose Ape, is it? I heard she was coming.’

‘Who?’

‘That one. Making up to Nina.’

‘Good lord, no. She’s no one. Mrs Panrast she’s called now.’

‘She seems to know you.’

‘Yes, I’ve known her all my life. As a matter of fact, she’s my mother.’

‘My dear, how too shaming.’

It’s a set, a group, a clique. They all know each other and many are related, couples, parents, children, aunts, cousins. Waugh’s novels themselves partake of this cliqueyness by featuring quite a few recurring characters. Figures we first met in the previous novel, Decline and Fall, include Lord Circumference and Miles Malpractice, little David Lennox the fashionable society photographer. Lord Vanbrugh the gossip columnist is presumably the son of the Lady Vanbrugh who appeared in D&F and Margot Maltravers, formerly Mrs Beste-Chetwynde who was a central character in the same novel, also makes an appearance under her new name, Lady Metroland, hosting a fashionable party. (She confirms her identity by whispering to a couple of Mrs Ape’s angels that she can get them a job in South America if she wishes, the reader of the previous novel knowing this would be at one of Lady M’s string of brothels there). And quite a few of these characters go on to appear in Waugh’s later novels. The effect is to create a comically complete ‘alternative’ version of English high society, with its narrow interconnectedness.

Thus we know from Decline and Fall that Lord Metroland married Margot Beste-Chetwynde. She was heiress to the Pastmaster title. Therefore her son, Peter Beste-Chetwynde, in time becomes Lord Pastmaster. Margot caused a great stir in Decline and Fall by going out with a stylish young black man. Here in Vile Bodies there is a sweet symmetry in discovering that her son is going out with a beautiful black woman. Hence Lord Metroland’s grumpy remark:

‘Anyhow,’ said Lord Metroland, ‘I don’t see how all that explains why my stepson should drink like a fish and go about everywhere with a negress.’

‘My dear, how rich you sound.’

‘I feel my full income when that young man is mentioned.’

Sociolect

The snobbery is enacted in the vocabulary of the text. Various social distinctions are, of course, directly indicated by possession of a title or one’s family. But also, of course, by how one speaks. Obviously there’s the question of accent, the way the upper class distinguish themselves from the middle and lower classes. But it’s also a specific vocabulary which marks one off as a member of the chosen, its sociolect – not only its slang but a very precise choice of key words which mark off a group, signal to other members one’s membership of the group and of course, signal to everyone else their very definite exclusion. Thus:

Divine Mrs Mouse thinks a party should be described as lovely. When her daughter describes the party she’s just been to as divine her mother tut tuts because that single word betokens the class above theirs, indicates that her daughter is getting above her station.

‘It was just too divine,’ said the youngest Miss Brown.

‘It was what, Jane?’

Because it is a word very much associated with the hardest core of the upper classiest of the Bright Young Things, represented in this book by the wild and heedless party animal, Miss Agatha Runcible.

Miss Runcible said that she had heard of a divine night club near Leicester Square somewhere where you could get a drink at any hour of the night.

Bogus This is another word much in vogue to mean simply ‘bad’ with the obvious overtone of fake:

- ‘Oh, dear,’ she said, ‘this really is all too bogus.’

- Miss Runcible said that kippers were not very drunk-making and that the whole club seemed bogus to her.

In fact their use of ‘bogus’ is cited by Father Rothschild as one of the things he notices about the younger generation. He takes a positive view of it, suggesting to his buddies Mr Outrage and Lord Metroland that the young actually have very strict morals and find the post-war culture they’ve inherited broken and shallow and deceitful. (In this way ‘bogus’ for the 1920s was similar to what ‘phoney’ was to be for Americans in the 1950s as popularised by Catcher In The Rye, ‘square’ was for hippies, and ‘gay’ is for modern schoolchildren).

Too ‘Too’ is an adverb of degree, indicating excess. Most of us use it in front of adjectives as a statement of fact, for example ‘This tea is too hot’. But the upper classes use it as one among many forms of exaggeration, indicating the simply superlative nature of their experiences, their lives and their darling selves. Used like this, ‘too’ doesn’t convey factual information but is a class marker; in fact its very factual emptiness, its semantic redundancy, highlights its role as a marker of membership:

- ‘I think it’s quite too sweet of you…’

- ‘Isn’t this too amusing?’

- ‘Isn’t that just too bad of Vanburgh?’

‘It was just too divine’ contains a double superlative, the adverb ‘too’ but also the adjective ‘divine’ itself, which is obviously being used with frivolous exaggeration. The party was divine. You are divine. I am divine. We are divine.

Such and so Grammatically ‘such’ is a determiner and ‘so’ is an adverb. So ‘so’ should be used in front of an adjective, ‘such’ in front of a noun phrase. In this narrow society, they are both used in much the same way as ‘too’, to emphasise that everything a speaker is talking about is the absolute tip top. After listening to someone telling us they had such a good time at such a wonderful party and spoke to such a lovely man, and so on, we quickly get the picture that the speaker lives a very superior life. To get the full effect it needs to be emphasised:

- ‘Such a nice stamp of man.’

- ‘It seems such a waste.’

- ‘Such nice people.’

- ‘Such a nice bright girl.’

There’s an element of risk in talking like this. Only a certain kind of person can carry it off. Trying it on among people who don’t buy into the entire elite idea, or among the real elite who know that you are not a member, risks ridicule.

So talking like this is a kind of taunt – I can get away with this ridiculous way of speaking but you can’t. The epitome of this verbal bravado is Miss Runcible, whose every word is littered with mannered vocabulary and superlatives, flaunting her superlative specialness, daring anyone else to compete.

Simply Paradoxically, for a very self-conscious elite, the pose is one of almost idiotic simplicity. Consider Bertie Wooster. His idiocy underpins his membership of the toff class. He is too stupid to do anything practical like have a job and his upper class idiocy is a loud indicator that he doesn’t need a job, but lives a life of privilege. Well one indicator of this attitude is use of the word simply.

- ‘I simply do not understand what has happened’

- ‘Nina, do you ever feel that things simply can’t go on much longer?’

- ‘Now they’re simply thrilled to the marrow about it .’

- ‘She’d simply loathe it, darling.’

- ‘Of course, they’re simply not gentlemen, either of them.’

Darling Preferably drawled, a usage only the very confident and suave can get away with.

‘Darling, am I going to be seduced?’

‘I’m afraid you are. Do you mind terribly?’

‘Not as much as all that,’ said Nina, and added in Cockney, ‘Charmed, I’m sure.’

Terribly Another denoter of frivolous giddy poshness, since the time of Oscar Wilde at least, via Saki and Noel Coward. Terribly and frightfully.

- ‘No, really, I think that’s frightfully nice of you. Look, here’s the money. Have a drink, won’t you?’

- ‘I say, you must be frightfully brainy.’

-making Many of these elements have survived the past 90 years, they continued into the equally frivolous Swinging Sixties and on into our own times, though often mocked, as in the TV series Absolutely Fabulous (1992 to 1996). A locution which is a bit more specific to this generation, or certainly to this book, is creating phrases by adding ‘-making’ to the end of an adjective. Thus:

- ‘Too, too sick-making,’ said Miss Runcible.

- ‘As soon as I get to London I shall ring up every Cabinet Minister and all the newspapers and give them all the most shy-making details.’

- Miss Runcible said that kippers were not very drunk-making and that the whole club seemed bogus to her.

- ‘Wouldn’t they be rather ill-making?’

- ‘Very better-making,’ said Miss Runcible with approval as she ate her haddock.

The usage occurs precisely 13 times in the novel, mostly associated with the most daring character, fearless Miss Runcible, and Waugh pushes it to a ludicrous extreme when he has her say:

‘Goodness, how too stiff-scaring….’ (p.174)

This locution made enough of an impression that Waugh singled it out in his preface to the 1964 edition of the novel for being widely commented on, and even taken up by a drama critic who included it in various reviews: ‘”Too sick-making”, as Mr Waugh would say.’ Did people actually say it, or was it a very felicitous invention?

Cockney

In my review of Decline and Fall I noted how much Waugh liked describing Cockney or working class characters and revelled in writing their dialogue. Same here. Thus a taxi driver tells Adam:

‘Long way from here Doubting ‘All is. Cost you fifteen bob…If you’re a commercial, I can tell you straight it ain’t no use going to ‘im.’

This turns out not to be a personal foible of Waugh’s. In Vile Bodies we learn that mimicking Cockney accents was highly fashionable among the creme de la creme of the Bright Young Things.

- ‘Go away, hog’s rump,’ said Adam, in Cockney,

- ‘Pretty as a picture,’ said Archie, in Cockney, passing with a bottle of champagne in his hand.

- ‘Look,’ said Adam, producing the cheque. ‘Whatcher think of that?’ he added in Cockney.

- ‘Good morning, all,’ she said in Cockney.

At university I knew very posh public schoolboys who had a cult of suddenly dropping into very thick Jamaican patois which they copied from hard-core reggae music (the extreme Jamaican pronunciation of ‘nay-shun’ kept recurring). Same kind of thing here – upper class types signalling their mockery and frivolity by mimicking the accents of the people about as far away from them on the social spectrum as possible.

Alcohol

Everyone’s either drunk, getting drunk or hungover. Their catchphrase is ‘Let’s have a drink’.

‘How about a little drink?’ said Lottie.

The American critic Edmund Wilson made the same comment about the literary types he knew in 1920s New York, and in general about ‘the Roaring Twenties’, ‘the Jazz Era’. Everyone drank like fish.

They went down the hill feeling buoyant and detached (as one should if one drinks a great deal before luncheon). (p.173)

Everyone was nursing a hangover. Everyone needed one for the road or a pick-me-up the next morning, or a few drinks before lunch, and during lunch, and mid-afternoon, and something to whet the whistle before dinner, and then onto a club for drinks and so on into the early hours. At luncheon with Nina’s father:

First they drank sherry, then claret, then port.

It goes without saying that these chaps and chapesses are not drinking beer or lager. Champagne is the unimpeachable, uncritisable, eternal choice for toffs and all occasions.

- (Unless specified in detail, all drinks are champagne in Lottie’s parlour.)

- Archie Schwert, as he passed, champagne bottle in hand, paused to say, ‘How are you, Mary darling?’

- Adam hurried out into the hall as another bottle of champagne popped festively in the parlour.

Drinking heavily and one more for the road and still partying at dawn are fine if you’re in your 20s (and well off and good looking). Give it 40 years and you end up looking and talking like the Major in Fawlty Towers as so many of these bright young things eventually did.

Ballard Berkeley as Major Gowen in Fawlty Towers

The extended scene at the motor races (Chapter Ten) contains a very funny description of four posh people becoming very drunk. Their progressive inebriation is conveyed entirely via their speech patterns, which become steadily more clipped and the subject matter steadily more absurd, so that when a race steward comes round to enquire where the driver of the car they’re supporting has gone to (his arm was hurt in an accident so he’s pulled into the pits and his car is empty) they immediately reply that he’s been murdered. When the steward asks if there’s a replacement driver, they immediately reply, straight faced, that he’s been murdered too.

‘Driver’s just been murdered,’ said Archie. ‘Spanner under the railway bridge. Marino.’

‘Well, are you going to scratch? Who’s spare driver?’

‘I don’t know. Do you, Adam? I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if they hadn’t murdered the spare driver, too.’

Since they each drink a bottle of champagne before lunch, the three posh friends start to come down at teatime and Waugh is as good on incipient hangovers as on inebriation.

The effect of their drinks had now entered on that secondary stage, vividly described in temperance handbooks, when the momentary illusion of well-being and exhilaration gives place to melancholy, indigestion and moral decay. (p.177)

More on this scene below.

Politics

The satirical point of view extends up into political circles, one of the jokes being that several of the most extreme and disreputably hedonistic of the Bright Young People are, with a certain inevitability, the sons and daughter of the leaders of the main parties and, since one or other of them is in power at any given moment, children of the Prime Minister.

In fact the mockery extends to the novel’s cheerfully satirical notion that the British government falls roughly every week. In the opening chapter we meet the Prime Minister who’s just been ousted, Outrage, and in the same chapter the supremely modish Miss Runcible. Only slowly does it become clear that she is, with a certain inevitability, the daughter of the current Prime Minister (Sir James Brown).

Half way through the book this Prime Minister is ousted because of stories about the wild party held at Number 10 which climaxed with his half-naked daughter, dressed as a Hawaiian dancer, stumbling drunkenly out the front steps of Number 10 and straight into the aim of numerous press photographers and journalists. Disreputable parties held by Tory toffs at Number 10? Well, it seems that in this, as so many other aspects of British life, nothing has really changed since the 1930s.

Moments of darkness

The best comedy, literary comedy as opposed to gag fests, hints at darker undertones. Shakespeare’s comedies tread, briefly, close to genuine cruelty or torment as, for example, in the hounding of Malvolio in Twelfth Night. Comedy generally is an unstable genre. For a generation or more we’ve had the comedy of cruelty or humiliation or embarrassment. I find a lot of modern comedy, such as The Office too embarrassing and depressing to watch.

Waugh’s comedy goes to extremes. It often includes incidents of complete tragedy which are played for laughs, or flicker briefly in the frivolous narrative as peripheral details, which are glossed over with comic nonchalance but which, if you pause to focus on them, are very dark.

It’s there in Decline and Fall when little Lord Tangent has his foot grazed by a shot from the starting gun at school sports day, the wound gets infected and he has to have the foot amputated. A lot later we learn, in a throwaway remark, that he has died.

Flossie’s death

Something similar happens here when a young woman, Florence or Flossie Ducane, involved in a drunken party in the room of one of the posh guests at the posh Shepheard’s Hotel attempts to swing from a chandelier which snaps and she falls to the floor and breaks her neck. Adam sees a brief report about it in the newspaper:

‘Tragedy in West-End Hotel.

‘The death occurred early this morning at a private hotel in Dover Street of Miss Florence Ducane, described as being of independent means, following an accident in which Miss Ducane fell from a chandelier which she was attempting to mend.‘

1. All kinds of things are going on here. One is the way moments of real tragedy provide a foil for the gay abandon of most of the characters. Each of these momentary tragedies is a tiny, flickering memento of the vast disaster of the First World War which looms over the entire decade like a smothering nightmare – all those dead husbands and brothers and fathers who everyone rushes round brightly ignoring.

(There’s a famous moment in the story, when Adam is hurrying to Marylebone station to catch a train out to the country pile of Nina’s father [Doubting Hall, Aylesbury], when the clock strikes 11 and everyone all over London, all over the country is still and quiet for 2 minutes because it is Remembrance Sunday. Then the 2 minutes are up and everybody’s hurly burly of life resumes. When I was young I read the handful of sentences which describe it as an indictment of the shallowness of Adam and the world, barely managing their perfunctory 2 minutes’ tribute. Now I see it as a momentary insight into the darkness which underlies everything, which threatens all values.)

2. On another level, the way Adam reads about Flossie’s death in a newspaper epitomises the way all the characters read about their own lives in the press; their lives are mediated by the media, written up and dramatised like performances. They read out to each other the gossip column reports about their behaviour at the latest party like actors reading reviews of their performances, and then, in turn, give their opinions on the columnists/critics’s writing up, creating a closed circle of mutual admiration and/or criticism.

3. On another, more obviously comic, level, what you could call the PR level, Adam smiles quietly to himself at how well the owner of the Shepheard’s Hotel, Lottie Crump, handled the police and journalists who turned up to cover Flossie’s death, smooth-talking them, offering them all champagne, and so managing to steer them all away from the fact that the host of the party where the death occurred was a venerable American judge, Judge Skimp. His name has been very successfully kept out of the papers. Respect for Lottie.

Simon Balcairn’s suicide

Then there’s another death, much more elaborately explained and described. Simon, Earl of Balcairn, has his career as a leading gossip columnist (writing the ‘Chatterbox’ column in the Daily Excess) ruined after he is boycotted by Margot Metroland and blacklisted from the London society through whom he makes his living. He gets Adam to phone Margot and plead to be admitted to her latest party, one she is giving for the fashionable American evangelist, Mrs Ape, but she obstinately refuses. He even dresses up in disguise with a thick black beard and gatecrashes, but is detected and thrown out.

Convinced that his career, and so his life is over, Simon phones in one last great story to his newspaper, the Daily Excess, a completely fictitious account of Margot’s party in which he makes up uproarious scenes of half London’s high society falling to their knees amid paroxysms of religious guilt and renunciation (all completely fictitious) – then, for the first time completely happy with his work, lays down with his head in his gas oven, turns on the gas, inhales deeply, and dies. It is, and is meant to be, bleak.

This feel for the darkness which underlies the giddy social whirl, and the complicated psychological effect which is produced by cleverly counterpointing the two tones, becomes more evident in Waugh’s subsequent novels, Black Mischief (1932) and A Handful of Dust (1934). In this novel he describes it as

that black misanthropy…which waits alike on gossip writer and novelist…

And it appears more and more as the novel progresses, like water seeping through the cracks in a dam. Nina starts the novel as the model of a social butterfly, utterly empty-headed and optimistic. After she and Adam have a dirty night in Arundel i.e. sex i.e. she loses her virginity, she ceases being so much fun. She finds the parties less fun. She starts to squabble with Adam. About half way through the novel she is, uncoincidentally, the peg for an extended passage which sounds a note of disgust at the book’s own subject matter (which is where, incidentally, the title comes from):

‘Oh, Nina, what a lot of parties.’

(…Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris–all that succession and repetition of massed humanity…. Those vile bodies…)

Waugh cannily sprinkles among the witty dialogue and endless parties a slowly mounting note of disgust and revulsion.

Comedy is adults behaving like children

From the moment of her deflowering Nina grows steadily more serious, almost depressed. You realise it’s because, in having sex, she’s become an adult. Things aren’t quite so much bright innocent fun any more. At which point I realised that the appeal of the Bright Young Things is, in part, because they behave like children, drunk and dancing and singing (OK, so the drinking is not exactly like young children) but at its core their behaviour is childish, persistently innocent and naive.

The Bright Young People came popping all together, out of some one’s electric brougham like a litter of pigs, and ran squealing up the steps.

Much comedy is based on adults behaving like children. It’s a very reliable way of getting a comic effect in all kinds of works and movies and TV shows. It occurs throughout this book. There’s a funny example when, at Margot Metroland’s party, the ageing ex-Prime Minister, Mr Outrage, gets caught up in the exposure of Simon Balcairn infiltrating the party in disguise but, because of the obscure way the thing is revealed with a variety of pseudonyms and disguises, the PM becomes increasingly confused, like a child among adults and he is reduced to childishly begging someone to explain to him what is going on. The comic effect is then extended when he is made to confess he experiences the same bewildering sense of being out of his depth even in his own cabinet meetings.

‘I simply do not understand what has happened…. Where are those detectives?… Will no one explain?… You treat me like a child,’ he said. It was all like one of those Cabinet meetings, when they all talked about something he didn’t understand and paid no attention to him.

Mr Chatterbox

Balcairn’s suicide creates a vacancy for a new ‘Mr Chatterbox’ and Adam happens to be dining in the same restaurant (Espinosa’s, the second-best restaurant in London) as the features editor of the Daily Excess, they get into conversation and so, with the casualness so typical of every aspect of these people’s lives, he is offered the job on the spot. ‘Ten pounds a week and expenses.’

Adam’s (brief) time as a gossip columnist turns into a comic tour de force. Just about everyone Simon mentioned in his last great fictitious account of Margot’s party (mentioned above) sues the Daily Excess (’62 writs for libel’!) with the result that the proprietor, Lord Monomark, draws up a list of them all and commands that none of them must ever, ever be mentioned in the paper again. This presents Adam with a potentially ruinous problem because the list includes ‘everyone who is anyone’ and so, on the face of it, makes his job as gossip columnist to London’s high society impossible.

He comes up with two solutions, the first fairly funny, the second one hilarious. The first one is to report the doings of C-listers, remote cousins and distant relatives of the great and good, who are often ailing and hard done by. The column’s readers:

learned of the engagement of the younger sister of the Bishop of Chertsey and of a dinner party given in Elm Park Gardens by the widow of a High Commissioner to some of the friends she had made in their colony. There were details of the blameless home life of women novelists, photographed with their spaniels before rose-covered cottages; stories of undergraduate ‘rags’ and regimental reunion dinners; anecdotes from Harley Street and the Inns of Court; snaps and snippets about cocktail parties given in basement flats by spotty announcers at the B.B.C., of tea dances in Gloucester Terrace and jokes made at High Table by dons.

This has the unexpected benefit of creating new fans of the column who identify with the ailments or afflictions of these ‘resolute non-entities’.

The second and more radical solution is simply to make it up. Like a novelist, Adam creates a new set of entirely fictional high society characters. He invents an avant-garde sculptor called Provna, giving him such a convincing back story that actual works by Provna start to appear on the market, and go for good prices at auction. He invents a popular young attaché at the Italian Embassy called Count Cincinnati, a dab hand at the cello. He invents Captain Angus Stuart-Kerr the famous big game hunter and sensational ballroom dancer.

Immediately his great rival gossip columnist, Vanbrugh, starts featuring the same (utterly fictional characters) in his column, and then other characters begin to mention them in conversation (‘Saw old Stuart-Kerr at Margot’s the other day. Lovely chap’) and so on. This is funny because it indicates how people are so desperate to be in the swim and au courant that they will lie to themselves about who they’ve seen or talked to. It indicates the utter superficiality of the world they inhabit which can be interpreted, moralistically, as a bad thing; but can also be seen as a fun and creative thing: why not make up the society you live in, if the real world is one of poverty and war?

But Adam’s masterpiece is the divinely slim and attractive Mrs Imogen Quest, the acme of social desirability, to whom he attributes the height of social standing. She becomes so wildly popular that eventually the owner of the Daily Excess, Lord Monomark, sends down a message saying he would love to meet this paragon. At which point, in a mild panic, Adam quickly writes a column announcing the unfortunate news that Mrs Quest had sailed to Jamaica, date of return unknown.

You get the idea. Not rocket science, but genuinely funny, inventive, amusing.

Father Rothschild as moral centre

Adam and Nina are invited to a bright young party held in a dirigible i.e. airship.

On the same night their more staid parents, politicians and grandees attend a much more traditional party for the older generation at Anchorage House. The main feature of this is the Jesuit Father Rothschild sharing with Mr Outrage and Lord Metroland a surprisingly mild, insightful and sympathetic view of the behaviour of the young generation. They have come into a world robbed of its meaning by the war, a world where the old values have been undermined and destroyed and yet nothing new has replaced them. A decade of financial and political crises ending up in a great crash. No wonder they make a point of not caring about anything. Genuinely caring about someone or something only risks being hurt. Hence the vehemence of the display of aloofness, nonchalance, insouciance, darling this and divine that and frightfully the other, and refusing point blank to ever be serious about anything.

In fact, Father Rothschild is given an almost apocalyptic speech:

‘Wars don’t start nowadays because people want them. We long for peace, and fill our newspapers with conferences about disarmament and arbitration, but there is a radical instability in our whole world-order, and soon we shall all be walking into the jaws of destruction again, protesting our pacific intentions.’

And this was written a few years before Hitler even came to power. Everyone knew it. Everyone sensed it. The coming collapse. The bright young things are laughing in the dark.

A touch of Auden

W.H. Auden often gets the credit for introducing industrial landscapes and landscapes blighted by the Great Depression into 1930s poetry, but it’s interesting to notice Waugh doing it here in prose. In a plane flying to the South of France, Nina looks down through the window:

Nina looked down and saw inclined at an odd angle a horizon of straggling red suburb; arterial roads dotted with little cars; factories, some of them working, others empty and decaying; a disused canal; some distant hills sown with bungalows; wireless masts and overhead power cables; men and women were indiscernible except as tiny spots; they were marrying and shopping and making money and having children.

One episode in the sad and dreary strand of English poetry and prose through the middle half of the twentieth century, E.M. Foster’s lament for the cancerous growth of London in the Edwardian era, D.H. Lawrence’s horrified descriptions of the mining country, John Betjeman’s comic disgust at light industrial towns like Slough, Philip Larkin’s sad descriptions of windswept shopping centres. But during the 1930s it had an extra, apocalyptic tone because of the sense of deep economic and social crisis.

Other scenes

The movie

Adam goes back to visit Nina’s father for a second time to try and borrow money, but is amazed to walk into the surreal scene of a historical drama being filmed at her father’s decaying country house (Doubting Hall, set in extensive grounds) by a dubious film company The Wonderfilm Company of Great Britain, run by an obvious shyster, a Mr Isaacs. (Worth noting, maybe, that Waugh has the leading lady of the movie, use what would nowadays be an unacceptable antisemitic epithet. Waugh himself has some of his characters, on very rare occasions, disparage Jews, but then they disparage the middle classes, politicians, the authorities and lots of other groups. Their stock in trade is amused contempt for everyone not a member of their social circle. Waugh comes nowhere near the shocking antisemitism which blackens Saki’s short stories and novels.)

Isaac is such a shyster he offers to sell Adam the complete movie, all the rushes and part-edited work for a bargain £500. Adam recognises a crook when he sees one. But his prospective father-in-law doesn’t, and it’s a comic thread that, towards the end of the novel, old Colonel Blount has bought the stock off Isaacs and forces his reluctant neighbour, the Rector of his church, to stage an elaborate and disastrous showing of what is obviously a terrible film.

(It is maybe worth noting that Waugh had himself tried his hand at making a film, with some chums from Oxford soon after he left the university, in 1922. It was a version of The Scarlet Woman and shot partly in the gardens at Underhill, his parents’ house in Hampstead.)

The motor race and Agatha

Adam, Agatha Runcible, Miles Malpractice and Archie Schwert pile into Archie’s car for a long drive to some remote provincial town to watch a motorcar race which a friend of Miles’ is competing in. It’s mildly comic that all the good hotels are packed to overflowing so they end up staying in a very rough boarding house, sharing rooms with bed which are alive with fleas. Early next morning they do a bunk.

The car race is described at surprising length, with various comic details (in the pits Agatha keeps lighting up a cigarette, being told to put it out by a steward, and chucking it perilously close to the open cans of petrol; this is very cinematic in the style of Charlie Chaplin).

There is a supremely comic scene where Miles’s friend brings his car into the pits and goes off to see a medic – one of the competitors threw a spanner out his car which hit our driver in the arm. A race steward appears and asks if there’s a replacement driver for the car. Now, in order to smuggle his pals into the pits in the first place, Miles’ friend had handed them each a white armband with random job titles on, such as Mechanic. The one given to Agatha just happened to read SPARE DRIVER so now, drunk as a lord, she points to it and declares: ‘I’m spare driver. It’s on my arm.’ The race steward takes down her name and she drunkenly gets into the racing car (she’s never driven a car before) her friends ask if that’s quite wise, to drive plastered, but she replies: ‘I’m spare driver. It’s on my arm’ and roars off down the course.

There then follow a sequence of comic announcements over the race tannoy as it is announced that Miss Runcible’s car (‘No 13, the English Plunket-Bowse’) has a) finished one lap in record time b) been disqualified for the record as it is now known she veered off the road and took a short cut c) has left the race altogether, taking a left instead of a right turn at a hairpin corner and last seen shooting off across country.

Our three buddies repair to the drinks tent where they carry on getting drunk. When ‘the drunk major’ turns up, promising to pay Adam the £35,000 that he owes him thanks to the bet he promised to make on a racehorse, they each have a bottle of champagne to celebrate.

Eventually it is reported that the car has been spotted in a large village fifteen miles away, town where it has crashed into the big stone market cross (‘ (doing irreparable damage to a monument already scheduled for preservation by the Office of Works)’).

Our threesome hire a taxi to take them there and witness the car wreck, mangled against the stone post and still smoking. Villagers report that a woman was seen exiting the car and stumbling towards the railway station. They make their way to the railway station and the ticket seller tells them he sold a ticket to London to a confused young woman.

(It may be worth noting that this entire chapter, with its extended and detailed description of competitive car racing, was almost certainly based on a real visit to a car race Waugh made, to support his pal David Plunket Greene. The real life race, which took place in 1929, is described, with evocative contemporary photos, in this excellent blog.)

Agatha’s end

To cut a long story short, after interruptions from other strands, we learn that Agatha sustained serious enough injuries in her car smash to be sent to hospital. But that’s not the worst of it. She had concussion and has periodic delusions, so she is referred on to ‘the Wimpole Street nursing home’. Here, in Waugh’s telegraphic style, we are given impressionistic snippets into her nightmares in which she is driving always faster, faster! and the comforting voice of her nurse trying to calm her as she injects her with a tranquiliser.

There’s a final scene in this strand where several of her pals pop round to visit her, bringing flowers but also a little drinky-wink, then some other appear and before you know it there’s a full scale party going on in her room, someone brings a gramophone, they all dance to the latest jazz tune. They even bribe the staid nurse with a few drinks and things are getting rowdy when, inevitably, the stern matron arrives and kicks them all out. Carry on Bright Young Things.

But, long story short, the excitement exacerbates Agatha’s shredded nerves and, towards the end of the narrative, we learn in a typically throwaway comment from one the characters, that Agatha died. Adam:

‘Did I tell you I went to Agatha’s funeral? There was practically no one there except the Chasms and some aunts. I went with Van, rather tight, and got stared at. I think they felt I was partly responsible for the accident…’

The fizzy bubbles mood of the opening half of the novel feels well and truly burst by this stage. Characters carry on partying and behaving like children but it feels like the moral and psychological wreckage is mounting up like a cliff teetering over them all.

Nina’s infidelities

The on again, off again relationship between Nina and Adam comes to a head when she declares she’s in love with a newcomer in their social circle, a man who speaks in even more outrageous posh boy phrases than anyone else. In fact, she casually informs Adam, she and Ginger got married this morning. Oh.

But this is where it gets interesting because Nina is such an airhead that she can’t really decide, she can’t make up her mind between Adam and Ginger. She goes off on a jolly honeymoon to the Med with him, but doesn’t like it one bit, he’s off playing golf most of the day. If you recall, Adam and Nina had had sex, at the hotel in Arundel, so there’s a more than emotional bond between them. Anyway, long and the short of it is she agrees to see him, to come and stay with him and, in effect, to start an affair with him as soon as she gets back to London.

It is all done for laughs but Waugh doesn’t need to draw the moral, to go on about psychological consequences, to editorialise or point out the moral implications for Nina and her set. All of this is conspicuous by its absence. It is left entirely to the reader to draw their own conclusions. Waugh’s text has the chrome-covered sleekness of an Art Deco statuette, slender, stylish, quick, slickly up to date.

He is the English F. Scott Fitzgerald, giving a highly stylised depiction of a generation in headlong pursuit of fun, drinks, drinks and more drinks, endless parties, with the shadow of the coming psychological crash looming closer and closer over his narratives.

The completely unexpected ending

The cinema show

Comedy of a sort continues up to the end, with the scene I mentioned before, of gaga old Colonel Blount, accompanied by Nina and Adam who are staying with him for Christmas, insisting on taking his cinematographic equipment round to the much put-upon local Rector, spending an age setting it up, and then blowing his entire household fuses in showing the terrible rubbish film which the director Isaacs has flogged to him.

It is a great comic scene if, to my mind, no longer as laugh out loud funny as the early scenes, because my imagination has been tainted by a silly death (Flossie), a suicide (Simon Balcairn), the nervous breakdown and death of pretty much the leading figure int he narrative (Agatha).

Anyway, after the power cut, the Colonel, Adam and Nina motor back to Doubting Hall for Christmas dinner and are in the middle of boozy toasts when the Rector phones them with the terrible news. War has broken out. War?

The last world war

In an extraordinary leap in subject matter and style, a startling break with everything which went before it, the very last scene discovers Adam, dressed as a soldier, amid a vast landscape of complete destruction, a barbed wire and mud nightmare derived from the grimmest accounts of the Great War and stretching for as far as the eye can see in every direction. It is the new war, the final war, the war Father Rothschild warned against, the war they all knew was coming and which, in a way, justified their heartless frivolity. Nothing matters. Jobs don’t matter, relationships don’t matter, sobriety or drunkenness, wild gambling, fidelity or infidelity, nothing matters, because they know in their guts that everything, everything, will be swept away.

Waugh’s humour continues till the end, but it is now a grim, bleak humour. For floundering across the mud landscape towards Adam comes a gas-masked figure. For a moment it looks as if they will attack each other, the unknown figure wielding a flame thrower, Adam reaching for one of the new Huxdane-Halley bomb (for the dissemination of leprosy germs) he keeps in his belt. God. Germ warfare. The utter ruined bottom of the pit of a bankrupt civilisation.

Only at the last minute do they realise they’re both British and then, when they take their masks off, Adam recognises the notorious Major, the elusive figure who took his money off him at Shepheard’s all those months (or is it years) ago, to bet on a horse, who he briefly met at the motor racing meet, and now gets talking to him, in that upper class way, as if nothing had happened at all.

‘You’re English, are you?’ he said. ‘Can’t see a thing. Broken my damned monocle.’

Now the Major invites him into the sanctuary of his ruined Daimler car, sunk past its axles in mud.

‘My car’s broken down somewhere over there. My driver went out to try and find someone to help and got lost, and I went out to look for him, and now I’ve lost the car too. Damn difficult country to find one’s way about in. No landmarks…’

It is the landscape of Samuel Beckett’s post-war plays, an unending landscape of utter devastation, dotted with wrecks of abandoned machinery and only a handful of survivors.

Once they’ve clambered into the car’s, the Major opens a bottle of champagne (what else?) and reveals a dishevelled girl wrapped in a great coat, ‘woebegone fragment of womanhood’. On closer examination this turns out to be one of Mrs Apes’ young girls, the laughably named Chastity. When quizzed, Chastity ends the narrative with a page-long account of her trials. It turns out that Margot Metroland did manage to persuade her to leave Mrs Ape’s religious troupe and go and work in one of her South American bordellos –so this fills in the details of the 3 or 4 girls we met during Decline and Fall who were being dispatched to the same fate.

Only with the outbreak of war, she returned to Europe and now presents in a breathless paragraph the story of her employment at a variety of brothels, being forced into service with a variety of conquering or retreating troops of all nations. The Major opens another bottle of champagne and starts chatting her up. Adam watches the girl start flirtatiously playing with his medals as he drifts into an exhausted sleep.

So, Waugh is pretty obviously saying, all of Western civilisation comes down to this: a shallow adulterer, a philandering old swindler, and a well-worn prostitute, holed up in a ruined car in a vast landscape of waste and destruction.

Aftershocks

Vile Bodies is marketed as a great comic novel and it is, and is often very funny, but as my summary suggests, it left me reeling and taking a while to absorb its psychological shocks. The deaths of Flossie, Simon and Agatha, and Nina’s slow metamorphosis into a thoughtless adulterer, all steadily darken the mood, but nothing whatsoever prepares you for the last chapter, which is surely one of the most apocalyptic scenes in the literary canon.

I had various conflicting responses to it, and still do, but the one I’m going to write down takes a negative view.

Possibly, when I was young and impressionable and first read this book, I took this devastating finale to be an indictment of the hollowness of the entire lifestyle depicted in the previous 200 pages. Subject to teenage moodswings which included the blackest despair, I took this extreme vision of the complete annihilation of western civilisation at face value and thought it was a fitting conclusion to a novel which, from one point of view, is ‘about’ the collapse of traditional values (restraint, dignity, sexual morality).

But I’m older now, and now I think it represents an artistic copout. It is so extreme that it ruins the relative lightness of the previous narrative. All the light touches which preceded it are swamped by this huge sea of mud.

And it’s disappointing in not being very clever. Up to this point any reader must be impressed, even if they don’t sympathise with the posh characters, by the style and wit with which Waugh writes, at the fecundity of his imagination, and the countless little imaginative touches and verbal precision with which he conveys his beautifully brittle scenarios.

And then this. Subtle it is not. It feels like a letdown, it feels like a copout. It’s not a clever way to end a noel which had, hitherto, impressed with its style and cleverness. It feels like a suburban, teenage Goth ending. It’s not much above the junior school essay level of writing ‘and then I woke up and it was all a dream’.

A more mature novel might have ended with the funeral of Agatha Runcible and recorded, in his precise, malicious way, the scattered conversations among the usual characters, momentarily brought down to earth and forced to confront real feelings, before swiftly offering each other and drink and popping the champagne. In this scenario the Major might have turned up as a fleeting character Adam still can’t get to meet, Nina unfaithful thoughts could have been skewered, Margot Metroland’s society dominance reasserted despite heartbreak over her dead daughter, Lord Monomark appointing yet another bright young thing as Mr Chatterbox, the ousted Prime Minister Mr Outrage still utterly confused by what’s going on, and maybe a last word given to sage and restrained Father Rothschild. That’s what I’d have preferred.

Instead Waugh chose to go full Apocalypse Now on the narrative and I think it was a mistake – an artistic error which became more evident as the years passed and the world headed into a second war, which he was to record much more chastely, precisely, and therefore more movingly, in the brilliant Sword of Honour trilogy.

Credit

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh was published in 1930 by Chapman and Hall. All references are to the 1983 Penguin paperback edition.

Related links

Evelyn Waugh reviews

- Decline and Fall (1928)

- Vile Bodies (1930)

- Remote People (1931)

- Black Mischief (1932)

- Ninety-Two Days (1934)

- A Handful of Dust (1934)

- Waugh in Abyssinia (1936)

- Scoop (1938)

- Work Suspended (1942)

- Put Out More Flags (1942)

- Brideshead Revisited (1945)

- Scott-King’s Modern Europe (1947)

- The Loved One (1948)

- Men at Arms (1952)

- Love Among the Ruins (1953)

- What is Waugh satirising in ‘Love Among The Ruins’?

- Officers and Gentlemen (1955)

- The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957)

- Unconditional Surrender (1961)

- The Complete Short Stories of Evelyn Waugh

- Evelyn Waugh: A Biography by Selina Hastings (1994)