This is an amazing exhibition by an extraordinary artist.

Marina Abramović is one of the most famous performance artists in the world. This major retrospective, filling all 11 rooms of the Royal Academy’s main exhibition space, takes you on a rollercoaster ride through her extraordinarily prolific, disruptive, endlessly inventive career and works.

Early years

Abramović was born in 1946 in Belgrade, then freshly liberated from Nazi occupation and the capital of newly communist Yugoslavia (now, of course, the capital of Serbia). There is a room devoted to her interaction with communism which we’ll come to later.

From 1965 to 1972 Abramović studied as an academic painter in Belgrade and Zagreb. However, towards the end of that period, she began to engage with the era’s radical political and artistic ideas which expanded the definition of art far beyond traditional media such as painting and sculpture. In the early 1970s she began to create work which would help define and shape the emerging genre of performance art.

What is performance art?

According to Wikipedia:

Performance art is an artwork or art exhibition created through actions executed by the artist or other participants. It may be witnessed live or through documentation, spontaneously developed or written, and is traditionally presented to a public in a fine art context in an interdisciplinary mode.

By definition, for most performance art you had to be there to experience the full thing, very similar to theatre. But it can, of course, be recorded in writing, photographs or video. The exhibition proceeds in more or less chronological order through Abramović’s career, using just such media i.e. video, photo and writings, to convey her numerous performances and activities, along with documentation and the props, or recreation of props, used in various performances.

Re-enactments

One of the exhibition’s huge attractions is that is also includes re-enactments of four of her most iconic pieces. These are being reperformed in the UK by performance artists live in the Academy galleries, for the first time. These live performances are reperformed by performance artists trained at the institute Abramović set up for the purpose, the Marina Abramović Institute. They are:

- Imponderabilia (1977) approximately 1 hour per performance

- Nude with Skeleton (2002) approximately 2 hours per performance

- Luminosity (1997) approximately 30 minutes per performance

- The House with the Ocean View (2002) performed continuously over 12 days, 24 hours per day

Stillness and endurance

What set Abramović apart from the beginning was her practice of taking everyday actions and turning them into strange and disturbing rituals through stillness and endurance. She pioneered using the live body in her work and has consistently tested the limits of her own physical and mental tolerance.

A lot of performance art is very confrontational, lots of shouting and dancing about, but what Abramović’s version confronts you with, above all, is the spectacle of her endurance. Most of her performances are very passive. If you were expecting wild dancing, gesticulation, recital, verbalising, forget it. All four of the performances put on here, and may of the others recorded on video, are about complete stillness. She holds the same pose for hours. But her ability to persist in ritualised positions raises all kinds of thoughts in the mind of the spectator – about human endurance, female endurance, and her personal endurance.

Endurance

For example, I found one of the most moving pieces a recent film projected on the wall of Abramović standing in a grimly derelict kitchen, dressed in a Victorian-style black dress, holding a bowl of milk which is full up to the brim. Standing stock still, without moving.

That’s all. But, of course, as the minutes tick by, this simple pose becomes steadily harder to maintain as her muscles protest at the rictus position, start quivering, then shaking which, of course, spills the white milk down the front of her dark dress, at first in small drops, then bigger drips.

This is clearly a video someone has taken of the original video, which explains the wobbly camera and zooming in and out. Still, it conveys the experience:

I can’t really put into words why I found this so staggeringly moving and poignant. So simple, so brilliant, saying something haunting about the human condition, the poverty of so many mundane human tasks, the pitifulness of human vulnerability.

Here’s a description of the fuller context from the Fondation Louis Vuitton website:

‘Carrying the Milk’ was filmed in the abandoned kitchen of the Laboral University of Gijón (Asturias, Spain) which was originally built to be an orphanage. In this self-portrait as a foster mother, the artist, austere and dressed in black, in the monastic setting of this time-ravaged kitchen, ‘religiously’ holds a container of milk. Despite an apparent stillness and a mind inhabited by action, the artist trembles, gradually spilling the white liquid on her long black dress. The milk references the initial purpose of the place, and the kitchen resembles that of her pious grandmother, where family life took place. With the addition of a mystical reference – the performances of ‘The Kitchen’ series are inspired by the life of Saint Teresa of Avila – and her contemplative nature, Marina Abramović explores the precarious balance between body and spirit, considering her work as a form of spiritual purification.

Confrontations

One of her most famous early works was ‘Rhythm 0’ from 1974. In this Abramović presented herself as an object to be acted upon. She stood motionless for eight hours alongside a table of 72 implements capable of being used for pain or pleasure, for the public to use on her as they wished.

Initially hesitant, some audience members became increasingly violent, stripping Abramović to the waist, cutting her skin, and even holding a gun to her neck. When the performance ended and Abramović moved, the public fled the galleries. The trauma of the experience turned part of the artist’s hair white.

Recreation of the trestle table covered with (scary) implements which Abramović invited gallery visitors to apply to her in ‘Rhythm 0’ (1974), with video footage projected on the wall behind. Photo by the author

What does that tell us about human nature, not just the audience’s which became steadily more abusive, but about Abramović’s for conceiving and then putting up with the performance? And then our attitude, 50 years later, comfortable gallery goes watching this ritual of degradation? Strange eddies of disturbing thoughts…

Forty later she performed ‘The Artist is Present’ at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She set up a table in the atrium and sat at it every day for three months. Members of the public were invited to sit silently opposite the artist for a duration of their choosing, their gazes meeting. The faces of both the audience members and Abramović herelf were filmed and photographed during the process. The footage indicates how much the experience challenged, discomfited and disturbed the visitors, sitting in the hot chair, forced into an intense one-on-one human confrontation but with none of the talking, greeting, etiquette and gesturing which normally defuses and manages such a situation. Instead the intense confrontation of human and human, triggering really deep feelings of disquiet and anxiety.

Installation view of ‘The Artist is Present’ showing a bank of stills of Abramović juxtaposed with stills of the many gallery visitors who sat opposite her. Photo by the author.

Imponderable

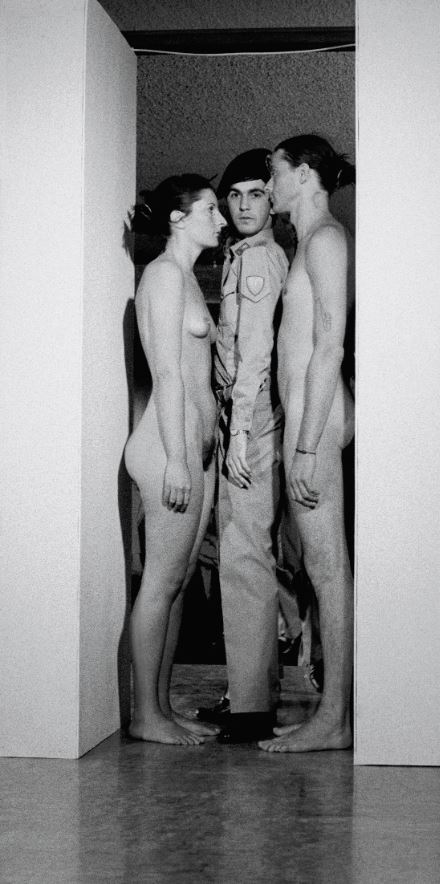

Several of the staged reperformances involve nudity (real live naked people!) in the gallery. The most famous one, and the most interactive, is the work titled ‘Imponderabilia’. This is an extremely simple but devastatingly effective idea. Have two naked people stand on either side of a narrow doorway so that visitors to the gallery are forced to squeeze between their naked bodies. Here’s a record of the original performance from 1977, featuring Marina and her performance partner Ulay.

Imponderabilia by Ulay / Marina Abramović (1977) Galleria Communale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Ulay / Marina Abramović

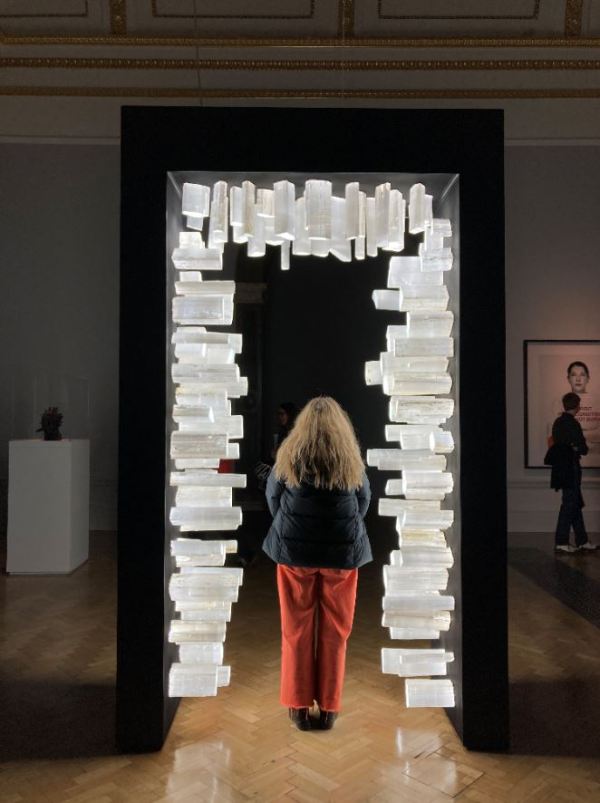

And here it is recreated now, in 2023, at the Royal Academy by some of the performers from the Marina Abramović Institute.

Installation view of ‘Imponderabilia’ by Marina Abramović (1977/2023) Live performance by Agata Flaminika and Kam Wan. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

I went through it, twice. You can’t go through facing forwards, you have to face one or other of the naked people. The friend I went with was amused to see whether I would face the boobs or the willy. Both times I faced the man to avoid the slightest accusation of wanting to brush against bare boobs.

In the event, this teenage question of embarrassment is irrelevant because it turns out to be a really intense, highly charged experience. It’s impossible to put into words but I felt a tremendous bolt of embarrassment, self consciousness, physical awareness, strangeness, which seized me for the 3 or 4 seconds it took to squeeze through.

Usually I go through an exhibition in a fairly sober, unruffled, detached mode and mostly react to works intellectually and clinically. But I was really disturbed by this brief experience. I loitered just past the door for a few minutes trying to figure out what just happened to me, almost feeling the need to sit down and recover. So did a middle-aged woman who came through me after me, and we both tried to put it into words but couldn’t, perplexed and disturbed.

Nudity

There’s one other nude performance in the show. In ‘Nude with Skeleton’ (2002) a naked woman lies on a dais or platform and two white-clothed assistants carefully position a full-length human skeleton on her body, then walk away. Then we, the audience, watch a naked woman quietly breathing, with every breath the white skeleton rising and falling. What is going on?

Installation view of ‘Nude with Skeleton’ (2002/2005/2023) Live performance by Madinah Farhannah Thompson. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives and Galerie Krinzinger © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

The question of nudity is worth discussing a bit. I live in England, a notoriously tightly wrapped, prudish society with a surprising amount of embarrassment around nudity and boobs in particular (page 3, the media’s obsession with side boob, under boob etc). So you have to address that in your mind and try to park it i.e. eliminate the prurient part of your reaction. Because clearly nudity is about something else, it’s about the human body in a completely open, exposed, vulnerable state. As I approached the two naked people my overwhelming feeling was how small they were, how open and defenceless. For a moment I was overcome with compassion for poor struggling humanity, its weakness and helplessness. No wonder so many people believe in God, surely this isn’t all there is, this poor bare forked animal.

But in a piece like the skeleton work you can see how nudity is appropriate because it very much is about the body, and the skeleton within us all, to which we will return. In other words, you can argue that nudity is appropriate when the subject matter is the human body, in the door piece, the skeleton piece.

As a general rule, it’s arguable that you have understood a work (of art or literature or whatever) when you are able to see round it enough to criticise it. What I’m driving at is that, although nudity may be appropriate in many works, you can question whether it’s necessary for all of them. There’s a film in the Communist room where Abramović starts off in a white doctor’s coat declaiming a speech to camera and something about her tightly wrapped hair and her stiletto shoes and the fact you couldn’t see a dress under the coat made me suspect she was about to strip off. I bet my friend she would and, after five or so minutes of talk, she did, indeed, take off the white coat to reveal a sheer black negligée in which she proceeded to do a very energetic folk (gypsy) dance, her boobs bouncing all over the place.

I didn’t find it erotic, I found it funny because it felt so predictable. It had the heavy logic of ten million soft porn movies and so it wasn’t surprising, unexpected or engaging. (It wasn’t total nudity, either, just to be clear.)

I think what I’m trying to say is that a focus on the body, the female body, and on the naked female body, can be surprising, inventive, confrontational, disorientating and creative. But it can also become a mannerism, a quick way of getting a reaction, a shock tactic.

So, back to the ‘Nude with Skeleton’ performance, the room it happened in was dark and packed, with many people sitting on the floor, like an infants’ school play, but what was chiefly interesting was watching the white-coated assistants trying to balance a skeleton on a naked person. This was trickier than it sounds because the naked person kept breathing, bits of their body moving up and down, so that bits of the skeleton kept slipping off the smooth skin. It was like watching someone setting up a tricky window display.

Once the white-coated assistants had finished and walked away and there was just a naked person lying under a skeleton, all the drama disappeared and the watchers stood up, stretched, looked around and walked away. Being a few yards away from a naked women felt surprisingly, well, meh… That also was odd, strange, worth pondering…

Collaborating with Ulay

‘Imponderabilia’ is just one of many many performances Abramović staged with German artist Ulay, real name Frank Uwe Laysiepen. They met in 1975 and Ulay was, for a decade or more, her partner in performance and life. One particularly big room features multiple screens on which are projected half a dozen black-and-white films from the 1970s in which they staged various interactions.

The curators blandly comment that these films ‘explore male and female dualities’ but you feel quite a massive amount more than that is going on, something profound, deep and searching about human nature, the human predicament, human limits.

In one they are standing facing each other and take it in turns to shout at the top of their lungs for a single breath. This feels very 70s, very primal scream therapy. On the screen next to it they are involved in a deep French kiss.

Shouting then snogging: installation view of some of the videos made by Marina Abramović and Ulay. Photo by the author

On the wall is a set of prints showing them facing away from each other but linked by their long hair which is plaited together into a Gordian knot.

In a particularly intense video, ‘Rest Energy’ – obviously more recent as it’s in colour (1980) – they pair stand with Ulay holding the feather end of an arrow strung in a bow while Marina grips the wooden bow itself and slowly leans back away from him, thus creating a greater and greater tension, with the arrow all the while pointing at her body. If he fumbled or slipped, the arrow would shoot through her neck. The ultimate trust exercise. As I watched I could feel my body tensing up and my breathing becoming more anxious.

The ultimate trust exercise: installation view of the Marina Abramović exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

The couple split up in 1989, in fact during one of their largest-scale performances.

Walking the Great Wall

For in the next room we learn that Abramović and Ulay set off to walk from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China, intending to meet somewhere in the middle and get married (!). In the event, by the time they actually met, after some 90 days of solo walking, they realised their relationship and their period of working together was over. This room displays film footage of each performer walking, titled ‘The Lovers, Great Wall Walk’ (1988), which leads up to a ritualised separation.

But that’s arguably the least interesting thing in the room. During the walk Abramović became fascinated by all things related to the wall, learning that it was built along the earth’s energy lines, reading up on Chinese and Tibetan medicine. She had become conscious of passing over stones that held vast quantities of geological and human energy.

One tangible output of this was a set of huge prints which seem to be a sort of brass rubbing of different parts of the wall, in different styles and patterns. These were just really lovely to look at, interesting to see the very wide range of brickwork involved, but also beautiful to look at as abstract patterns and designs.

Installation view of ‘The Lovers, Great Wall Walk, Wall Rubbings’ by Marina Abramović (1988) Photo by the author

The room also features urns in two media. There are two big black urns, one shiny, one with a dull matt finish which, apparently, symbolise Ulay and Abramović and, more generally, the male and female principles – titled ‘The Sun, The Moon’ (1987) . According to the curators:

They speak to themes of the duality and symbiosis present in many of the couple’s works, yet also marked the breakdown of their artistic and personal connections. Abramović realised: ‘The vases represented us and our inability to perform together anymore.’

They are big and black and a pleasant shape. Nice things to look at.

Installation view of the urns, the urn prints and the Great Wall of China rubbings © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

But they’re given an extra dimension by a set of big prints of urns on the wall behind them, three urns and a scarf, titled ‘Modus Vivendi: Urn 1, Urn 2, Veil, Urn 3’. Like the brick rubbings and the two urns this doesn’t seem to have much to do with performance in any way. They’re just beautiful and beguiling images, lovely pastel colours, shimmering asymmetrical images, and a pleasing sense that they’re made on rough-hewn parchment adding to a sort of rough-hewn ethnic finish.

Video

Here’s an excerpt from what looks like a longer video about Abramović and Ulay’s relationship which, alas, makes them sound like everybody else, but does include some footage of the bow and arrow performance, of their earlier confrontational performances (mutual slapping) then goes heavy on the ill-fated Wall of China walk.

The Communist Body

This room brings together works about or referencing Abramović’s origins in the communist state of the former Yugoslavia. Communism was obviously a repressive system but it did preserve peace and security among the Balkans’ squabbling nationalities, a situation which swiftly broke down into brutal internecine wars with the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991.

Abramović’s parents Danica Rosić and Vojin Abramović had been partisan fighters in the Second World War. Celebrated as heroes they were rewarded with coveted state jobs. The strictures of communist ideology – from extreme physical discipline to restricted freedom of speech – shaped Abramović’s early years and her subsequent formation as an artist.

The five-pointed communist star appears in many early pieces, as she explored communist ideology and its impact on herself and others. In ‘Rhythm 5’ (1974), this took the form of a wooden structure which was set alight as she lay within it. The resultant dense smoke was suffocating and caused the artist to faint.

Installation view of the long panel displaying photos of the performance of ‘Rhythm 5’ by Marina Abramović. Photo by the author

The following year she incised a star into her abdomen as part of the performance ‘Lips of Thomas’, leaving behind an indelible scar on her body. Abramović left Belgrade in 1976 but continued to feel a close tie to the region.

Balkan Baroque

Obviously she was affected when, from 1991 onwards, her native country collapsed into a series of interlocking civil wars marked by astonishing brutality. At the Venice Biennale in 1997 she presented ‘Balkan Baroque’, a complex and multifaceted reflection on her homeland.

This consisted of two elements, videos and an activity. On the wall were projected three videos, in the centre a film of Abramović dressed in the white coat of a doctor and reciting a folk story about a rat catcher, before taking off her coat to reveal herself as (in her own words) ‘a sexy dancer’ who proceeds to dance the Hungarian Czardas. In smaller projections to left and right of her film of her father and her mother, filmed in a series of static poses reacting to the narrative and then the dance, the father ending up with a pistol in his hands, the mother at first showing empty hands and then with crossed hands on her eyes.

Meanwhile, part two of the piece was Abramović herself sitting amid a huge pile of animal bones fresh from the abattoir and slippery with blood and gristle, and attempting to wash and clean it. In her own words:

It was summer in Venice, very, very hot and after a few days already worms start coming out of the bones. And the smell was unbearable. The whole idea that by washing bones and trying to scrub the blood, is impossible. You can’t wash the blood from your hands as you can’t wash the shame from the war. But also it was important to transcend it, that can be used, this image, for any war, anywhere in the world. So to become from personal there can be universal.

The video is here, in the Royal Academy but, regrettably, the pile of bones on display is antiseptically clean and dry and no woman is sitting amid them desperately trying to wash the blood off herself. British Health and Safety regulations. Shame. Rotting bloody bones would have freaked everyone out.

‘Balkan Baroque’ by Marina Abramović,, a 4-day performance at XLVIII Venice Biennale (June 1997). Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović

The Hero

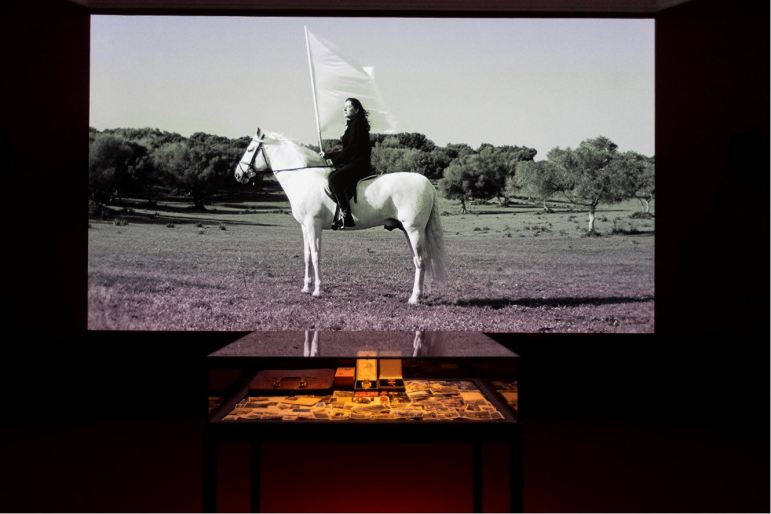

Three years later, Abramović’s father, Vojin Abramović, passed away. In memory of him she created ‘The Hero’. This consists of two elements: 1) a big projection of a black-and-white shot of her sitting – characteristically stationary – on a white horse, holding a white flag flapping in the wind to the accompaniment of an elegiac arrangement of the Yugoslavian national anthem. And 2) a display case in front of it showing a collection of memorabilia, army membership and medals and so on associated with her father.

Installation view of ‘The Hero’ by Marina Abramović (2001) showing the film and the display case devoted to her father. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives and Luciana Brito Galeria © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

To my irritation I learn that this film was displayed on a hoarding in Piccadilly Circus as recently as last year but I managed to miss it:

Surprisingly, this isn’t an ironic reference to heroes and heroism. She genuinely means it. In fact the piece is accompanied by a Heroes’ Manifesto:

Heroes should not lie to themselves or others

Heroes should not make themselves into an idol

Heroes should look deep inside themselves for inspiration

The deeper they look inside themselves, the more universal they become

Heroes are universe

Heroes are universe

Heroes are universe

Heroes create their own symbols

Symbols are the Heroes’ language

The language must then be translated

Sometimes it is difficult to find the key

Heroes have to understand silence

Heroes have to create a space for silence to enter their soul

Silence is like an island in the middle of a turbulent ocean

Heroes must make time for the long periods of solitude

Solitude is extremely important

Away from home

Away from family

Away from friends

Heroes should have more and more of less and less

Heroes should have friends that lift their spirit

Heroes have to learn to forgive

Heroes have to learn to forgive

Heroes have to learn to forgive

Heroes have to be aware of their own mortality

For the Heroes, it is not only important how they live their life but also how they die

Heroes should die consciously, without anger, without fear

Heroes should die consciously, without anger, without fear

Heroes should die consciously, without anger, without fear

If we wanted, we could pause here and reflect on the disastrous impact of Serb nationalism on the Balkans in the 1990s, the atrocities committed by the Serbian Army and paramilitaries (documented in, for example, books by Anthony Loyd and Michael Ignatieff), the 1,425 day-long siege of Sarajevo by the Yugoslav/Serbian Army, and so on. It seems odd, and maybe distasteful, to create such an unironic image. The way it’s placed next to the Balkan Baroque mound of bones suggests the progression from heroic nationalist rhetoric to villages full of butchered peasants.

Doors

To quote the curators:

Every day we move without thinking through a series of thresholds, each ushering us between different experiences and states of being. Throughout cultures, portals have also been understood as symbolic sites of passage between good and evil, darkness and light, paradise and hell, life and death. Building on her earlier ‘Transitory Objects’, Abramović has created numerous works that give representation to transition and transformation. ‘The portal, for me, is really about a changed state of consciousness. It’s about how to access different temporal dimensions from the cosmic to the earthly.’

Hence this portal adorned with illuminated crystals. This was first displayed at the Modern Art Museum in Oxford, whose website provides further details:

A 297cm-tall portal adorned with 190 selenite crystals jutting out from each internal side. Selenite is a variety of gypsum with properties that conduct light and act as a natural optic fiber. A custom-made circuit of LED panels transmits light through the crystals, which emerges from the absorbant black-painted steel structure. This creates a portal with an intensely illuminated centre.

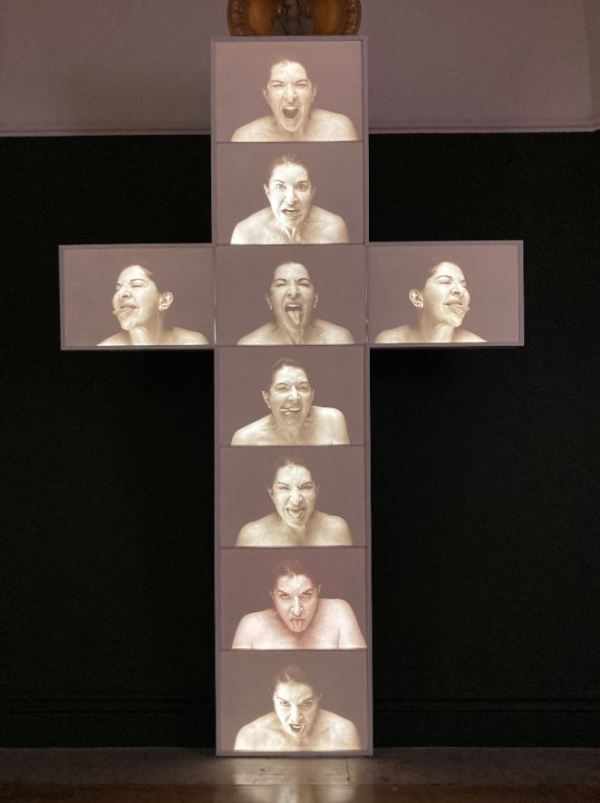

Four crosses

In the main atrium space of the galleries are arrange four enormous crosses made up of still photos of the artist pulling a wide variety of faces (2019). In their positioning, leaning out from the walls, they reference the language of Slavic icons and I couldn’t help thinking that, quite obviously, she’s replaced the figure of the crucified Christ, Son of God, with herself, an act, you might think, of quite staggering narcissism and which reflects back through the entire show the thread of self-promoting exhibitionism which is part and parcel of performance art. Here I am. I am a work of art.

Alternatively, you could give it a feminist interpretation, saying the idealised figure of a dead man representing the dead hand of patriarchal religion has been replaced by the reality of a living woman in all her emotional messiness and reality.

Or split the difference with an ungendered, humanist interpretation, that an idealised religious figure designed to take our thoughts away from this world has been replaced by a real live human being in all her emotional complexity and predicaments.

The House with the Ocean View

The exhibition concludes with an enormous installation, the reperformance of ‘The House with the Ocean View’. This involves a mockup of two floors of an apartment with 3 rooms on the first floor and open to the viewing public like rooms in a doll’s house when the front has been opened.

First performed by Abramović in 2002, she lived continuously for 12 days in this ‘home’ of only three spaces in the Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. Abramović fasted by only drinking water, while converting the most basic functions of living into rituals. Audiences were invited to witness it on the condition that they didn’t speak. Held a year after 9/11, the work, according to the curators, ‘created a collective vigil’. Maybe. Or maybe it was an odd, strangely engaging, slightly bewildering, boring and yet hypnotic experience…

Interactive fun

The Chinese adventure was her first time not performing directly in front of an audience. After the relationship with Ulay broke down she had to start again. Part of this was thinking about pieces which still interact with the audience but without the presence of the artist. Hence her series of ‘Transitory Objects For Human Use’. These are objects designed to make the audience the central participant of the artwork without requiring the presence of the artist. According to the curators:

Rather than sculptures or items of furniture, the ‘Transitory Objects’ act as tools allowing viewers to access the energy and curative power of the crystals and metal that form them, based on traditional Chinese medicine’s correspondences between minerals and parts of the body.

In practice these are a series of green metallic head rests, seats and stands stuck onto the wall of the gallery and visitors are encouraged to interact with them – standing on podiums, resting your forehead against head rests, sitting astride the metal chairs. Maybe visitors felt ‘traditional Chinese medicine’s correspondences between minerals and parts of the body’ but these provided posing and photo opportunities for scores of gallery goers queuing up to strike a pose and tell their friends all about it on Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok.

Installation view of ‘White Dragon’ by Marina Abramović (1989) Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

Masks

Along the wall of the room with the woman lying under a skeleton is a series of works which, when you look at them, seem to be prints of the iconic images of Abramović pulling faces. It’s only when you approach them sideways that you realise these are 3-D sculptures, with the faces cut into successive layers of alabaster.

These are ‘Five Stages of Maya Dance’ (2013/2016) in which she performed to camera the extremes of human expression and then the photographs were carved in negative relief on alabaster slabs:

turning them into performative sculptural objects that memorialise the artist’s performance yet transform into rough stone when approached.

An entertaining 3-D optical illusion. One more wonder, delight and entertainment in a brilliant exhibition.

‘Five Stages of Maya Dance’ by Marina Abramović. Left: one of the sculptures face-on. Right: the series of five sculptures from the side. Photo by the author.

Conclusion

I have commented on barely half the works on display. It’s a massive, mighty exhibition. Amazing. Mind blowing. An extraordinary body of work which helped define and shape performance art for its 50 year history, and continues to amaze and challenge and disturb and impress and inspire. Epic. Must see. Best exhibition in London.

Related links

- Marina Abramović at the Royal Academy continues until 1 January 2024

- Marina Abramović biography