This is a small-ish (five rooms) but excellent, vivid, thought-provoking and FREE exhibition about the work and legacy of the legendary British photojournalist, filmmaker and humanitarian, Tim Hetherington (1970 to 2011).

It brings together 65 of his striking photos taken from warzones but also a lot more too, including: four large films projected onto wall-sized screens, half a dozen or so short interviews watchable on video screens with headphones, four or five of the cameras he actually used and one of his smartphones, plus documentary artefacts like his diary and notes, and examples of his half dozen or so photobooks.

Installation view of the Liberia room in ‘Storyteller: Photography by Tim Hetherington’ at IWM London. Photo by the author

The exhibition makes several key points:

1. Hetherington was uncomfortable with being just a war photographer. He felt a greater responsibility to the stories and to the people he met than that. And so he spent longer than is usual for traditional war snappers with the communities and fighters he was covering, and often returned months or years later. So while he continued to work as a photographer on assignment from the likes of the Vanity Fair magazine, he also developed the notion of ‘projects’, generally leading up to photobooks (see list below).

2. Hetherington was tremendously reflective and fluent. He appears not only in the four films (detailed below) and in the half dozen or so video interviews, but also via his own words – there are short pithy quotes printed around the walls. As to the content, it tends to be variations on the same basic idea which is the responsibility he felt to the people he photographed, the obligation he felt to dig beneath the stereotyped images of, for example, Catastrophe in Africa, to try to give his subjects more agency and dignity.

3. Hetherington also broke with convention in his use of vintage cameras through the early 2000s – a time of major advances in digital photography – and the display cases contain some of his actual cameras, such as his Rolleiflex 2.8 FX camera where he had to manually wind the film on with a side handle and manually set the focus. (Elsewhere we can see his Mamiya 7 film camera and Vivitar flash gun.)

The idea was that slowing the photographing process down him gave more freedom to interact with people, while challenging him to take more carefully considered photographs.

Installation view of the Libya room in ‘Storyteller: Photography by Tim Hetherington’ at IWM London. Note the display case containing one of Tim’s cameras and flash attachments next to a contact sheet and notebook.

Projects

1. Healing Sport

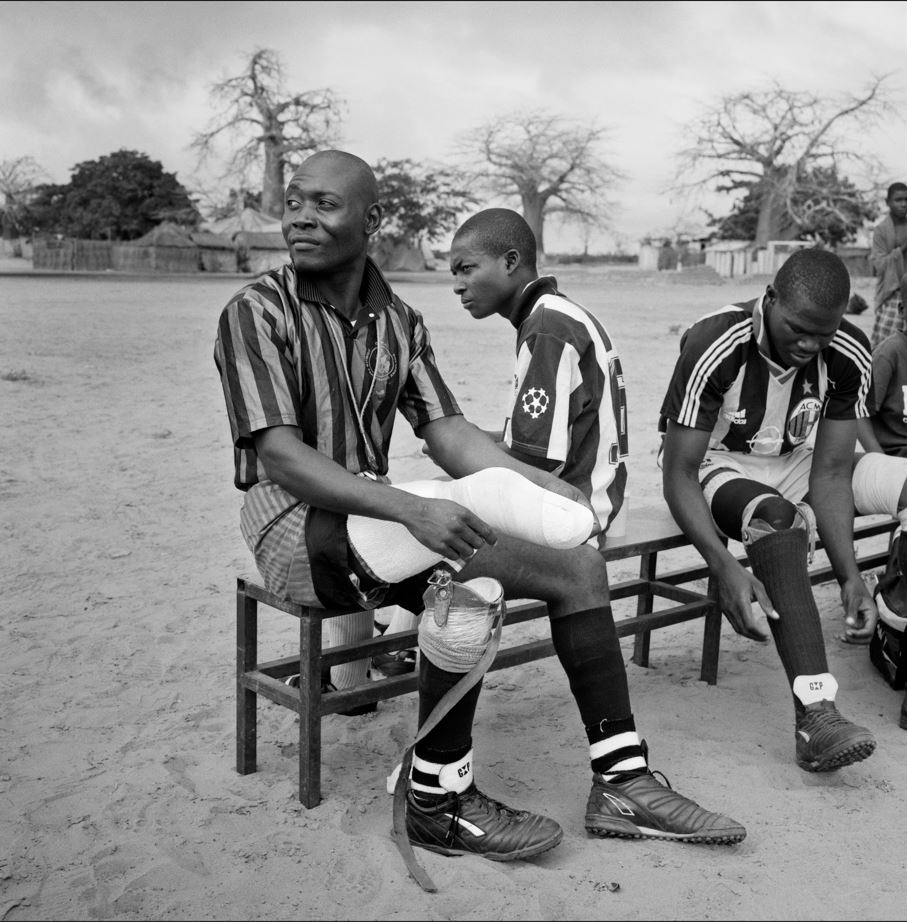

In 1999, Hetherington began work on his first large-scale project, ‘Healing Sport’. The idea was to look at the role of sport in ‘healing’ or creating spaces for reconciliation after conflict in war-torn countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone and Angola.

An amputee about to take to the field for a friendly football match at a war veterans camp situated on the outskirts of Luanda, Angola. June 2002, by Tim Hetherington © IWM (DC 63058)

2. Liberia (2003 to 2007)

The second Liberian Civil War (1999 to 2003) was Hetherington’s first experience of an active frontline. He joined up with journalist James Brabazon to capture the story of the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) as they marched on the capital, Monrovia, to overthrow Liberian president Charles Taylor.

For his initial assignment Hetherington photographed and filmed LURD combatants over a period of five weeks, but later returned to work, and at times live in Liberia as it transitioned from civil war to democracy. The result was the photobook ‘Long Story: Bit by Bit: Liberia Retold‘, a combination of photography, oral testimony and personal memoir, along with video footage which was incorporated into a documentary film.

A Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) combatant in Liberia, June 2003 by Tim Hetherington at IWM London © IWM (DC 64010)

3. Afghanistan (2007 to 2008)

In 2007 Hetherington travelled with journalist Sebastian Junger to cover the front line of the war in Afghanistan. They were embedded in a platoon of the 173rd Airborne Brigade based at an isolated outpost called Restrepo in the Korengal Valley.

Initially it was an assignment for Vanity Fair magazine and Hetherington and Junger took turns to embed with the platoon for periods during its 15-month deployment, eating, sleeping and going on operations with the soldiers.

The idea is that the photos here avoid the clichés of battle and instead show these young Americans at work and play, off-duty, rough-housing and larking about and, in a famous sequence, sleeping. So evocative was the image of these tough young men shown in the vulnerable state of sleep that it gave rise to one of his films (see below).

A sleeping soldier from the United States Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley by Tim Hetherington © IWM (DC 66144)

In fact the boys got a lot of material from this deployment, resulting in news items and magazine features, several books, a video installation and ‘the multi-award winning and Oscar-nominated documentary film, Restrepo‘. A lot of product, in other words.

The wall caption optimistically says that spending this much time with the soldiers, building up a high level of trust so that they let him capture them in all kinds of moods – all this ‘led him to ask questions through his work about the nature of masculinity’. The nature of masculinity. Really? This is the kind of modish boilerplate that curators write when they haven’t got anything to say. I don’t think the photos ask any questions whatsoever about masculinity, to any male it looks like a lot of male soldiers hanging out, training, play-fighting, smoking, and sleeping. Being soldiers, in other words.

US soldiers filling sandbags at the Restrepo outpost in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley by Tim Hetherington © IWM

4. Libya (2011)

This was his final project, left unfinished at his death. During the Arab Spring (see my review of The New Middle East: The World After The Arab Spring by Paul Danahar) a wave of anti-government protests across North Africa and the Middle East starting in January 2011, Hetherington embarked on a new project to document the battle to overthrow Colonel Gaddafi’s regime in Libya.

Apparently, Hetherington left notes saying he wanted his photographs to bring out the ‘staged’ and ‘theatrical’ aspect of modern conflict, how a lot of it is performed by combatants who were raised on Vietnam or Rambo movies.

Installation view of the Libya room in ‘Storyteller: Photography by Tim Hetherington’ at IWM London. Photo by the author

It was here, on 20 April 2011, that Hetherington was killed while covering the front lines in the besieged city of Misrata. It’s unclear whether he was wounded by shrapnel from a mortar shell or a rocket-propelled grenade. He was badly wounded but still alive when he was loaded into a van to be driven to hospital but bled to death on the journey. The same attack killed photographer Chris Hondros, badly wounded photographer Guy Martin and wounded photographer Michael Christopher Brown.

Four films

Two of the rooms are dark spaces set aside for video presentations. One of them contains three short films on a loop which have been created for three screens i.e. split-screen films, being:

- Healing Sport (6 minutes 24 seconds)

- Sleeping Soldiers (4 minutes 34 seconds)

- Liberian Graffiti (1 minute 22 seconds)

As you can see, they each relate directly to the three main zones of his reporting and the projects.

The cinema room at ‘Storyteller: Photography by Tim Hetherington’ at IWM London showing the three screens showing different images, part of ‘Sleeping soldiers’ (photo by the author)

At the other end of the series of rooms – in effect the exhibition’s climax – is a dark room dedicated to showing the standalone film, ‘Diary’.

- Diary (19 minutes 8 seconds)

All the films are to an extent experimental, more like art films than news or reportage. They are OK but I’ve seen better. They feel almost like student works. Hetherington might have been an inspired photographer but producing a film, even of only a few minutes duration, is a completely different business. Our movie-saturated culture demands very high standards. And speaking as the series producer of various TV magazine shows, there’s a lot of craft involved, especially in counterpointing images and sound, an often overlooked but absolutely crucial aspect of film-making.

Thus, sorry to burst anyone’s bubble, but I felt Diary was poor. I especially disliked the use of the voice of what is presumably his girlfriend, recorded from phone messages: on a trivial level a) because it is, with horrible inevitability, American (Vanity Fair; US troops; based in New York; American girlfriend); but, more seriously, b) because it’s a pretty primitive concept to cut scenes of lonely sad hotel rooms, showers and beds, splice these with a few hairy moments out on patrol with troops or driving in a car which comes under attack, and then splice in the voice of girlfriend. It conveys quite a teenage aesthetic. Is he saying the life of a foreign correspondent/photographer can be lonely and isolating? Not a very interesting insight. And purely in terms of technique, hardly any of the shots are particularly good, and the sad girlfriend’s voice strategy feels corny. A student effort.

Self-absorption

This brings me to a thought which won’t make me any friends, which is that there’s an awful lot about him in the exhibition.

The wall labels make the same point over and over that he stayed far longer than usual among the communities and got to know people really well in order to tell their stories blah blah blah but the funny thing is we don’t hear any of their stories.

The LURD fighters in Liberia, the grunts in Afghanistan, I don’t think a single one of them is named. Instead, what we do get a lot of is how this or that project helped Tim grow as a person. In the interviews he explains that this project or that moment or the other photo represented a turning point, when he came to realise x, y or z, had a new insight, helped his evolution as a photographer. An overwhelming amount of it is about Tim, Tim, Tim and I was disappointed with the thinness of analysis of the actual conflicts he covered, Liberia, Afghanistan, Libya.

Thus in the ‘Healing Sport’ film, number 1) he is interviewed throughout the film, in fact the spine of the film is an extended interview with Tim Hetherington. 2) None of the sporting figures he photographed is interviewed or even mentioned by name. 3) He doesn’t talk about the sports so much as what the sports meant for him, about how the thing developed into one of his projects and dovetailed his interest in going behind the scenes of a story along with his concept of the Trojan Horse i.e. shedding light on conflict via a more acceptable subject i.e. sport. The core of the film is Hetherington telling us how he conceived and evolved the project and what it meant for him. It is, once again, all about him.

This self-absorption comes over in the captions scattered around the walls. Of the Afghanistan photos he wrote:

I didn’t want to pretend this was about the war in Afghanistan. It was a conscious decision. It comments on the experience of the soldier. It’s about brotherhood.

Not particularly offensive, you might think, but it’s about him and his decision-making. It’s a bit more obvious in another quote:

I became much more interested in the interrelationships between the soldiers and my own relationship to the soldiers than I was in the fighting.

In the Liberia section:

I have no desire to be a kind of war firefighter flying from war zone to war zone.

I do not set out to make a work of journalism but rather a visual novel that draws upon real people and places.

The attitude is best epitomised in this one:

My examination of young men and violence or of young men…it’s as much a journey about my own identity as it is about those young soldiers.

The wall captions tell us that he took many portraits of himself and that he was a prolific diarist, capturing his moods and thoughts and ideas. There’s an electronic version of his last journal which we can read via a touch screen. No surprise, maybe, that a man who was a prolific diarist made a film titled ‘Diary’ of which he wrote:

Diary is a highly personal and experimental film that expresses the subjective experience of my work, and was made as an attempt to locate myself after ten years of reporting.

Even the exhibition curator, Greg Brockett, agrees:

‘In the process of curating this exhibition, and the years I have spent cataloguing and researching Tim Hetherington’s archive, I have discovered just how driven Hetherington was to explore his own fascination with the world through the lens of conflict. I’ve uncovered a depth of personal insight to Hetherington’s character and his thoughtful approach to his work.’

I, I, I – the exhibition overflows with Hetherington’s sense of himself as an artist and maker gifted with particularly fine feelings and a special commitment to the people he photographed and yet … we get almost no sense of the personhood of any of the people he photographed, no names, no sustained engagement with them and little or no analysis of the conflicts he covered.

The amazingly vivid photo of the Liberian fighter looking at us with a hand grenade by his side, it would have been so much more powerful if we’d learned something about his story, his hopes, how he ended up where he is, rather than another sugary quote from Hetherington about his aims as an artist and his never-ending attempts to ‘locate himself’…

The Tim Hetherington cottage industry

A lot of people have taken Hetherington at his word as a mighty photographer and film-maker because, following on from all the self-centred quotes, I was amazed to learn of the small cottage industry which has grown up around him.

A year after his death, in 2013, Hetherington’s parents set up the Tim Hetherington Trust.

In 2013 his buddy Sebastian Junger made a documentary film about him, ‘Which Way Is the Front Line From Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington’ (2013).

In 2016 a Tim Hetherington Fellowship was set up by World Press Photo and Human Rights Watch.

In 2016 the Tim Hetherington Photobook Library was set up in the Bronx, New York which appears to simply be all the books he owned when he died, as if they are the sacred relics of a saint.

And in 2017 the Imperial War Museum received the complete Tim Hetherington Archive from the Tim Hetherington Trust and set about ordering and cataloguing them, one result of which was their setting up a Tim Hetherington and Conflict Imagery Research Network.

So Hetherington is not only a famous war photographer and Oscar-nominated film-maker but this exhibition obviously represents the museum’s first opportunity to showcase their (relatively) newly-acquired archive and give it a real splash.

Inevitably, the IWM has also produced a book to accompany the exhibition, Tim Hetherington: IWM Photography Collection on Amazon. One more piece of Hetherington merch to join the photobooks, magazine articles, interviews and documentaries.

After a while I felt positively overloaded with Hetheringtonia, with Hetherington-mania. What will be next? A musical based on his life? Nomination as a saint?

He was a great photographer. He made a vivid war documentary. He talked a very good game in his pukka private school tones (Stonyhurst College and Oxford) and this exhibition is a scholarly, thorough and imaginative (the interactive journal, the cameras) act of respect by the new holders of his archive. But if you want to understand more about the actual conflicts he covered (Liberia, Afghanistan, Libya) and the people affected by them, I don’t think this is the place to do it.

Related links

- Storyteller: Photography by Tim Hetherington continues at the Imperial War Museum until September 2024 and it is FREE

- Tim Hetherington collection and Conflict Imagery Network (IWM)

- Tim Hetherington: Photojournalist and filmmaker (IWM)

- Tim Hetherington: IWM Photography Collection on Amazon

- Tim Hetherington Wikipedia page

- Tim Hetherington Trust website