Note: to avoid misunderstanding, I believe Freud is a figure of huge cultural and historical importance, and I sympathise with his project of trying to devise a completely secular psychology building on Darwinian premises. Many of his ideas about sexuality as a central motive force, about the role of the unconscious in every aspect of mental life, how repressing instinctual drives can lie behind certain types of mental illness, his development of the talking cure, these and numerous other ideas have become part of the culture and underlie the way many people live and think about themselves today. However, I strongly disapprove of Freud’s gender stereotyping of men and women, his systematic sexism, his occasional slurs against gays, lesbian or bisexuals and so on. Despite the revolutionary impact of his thought, Freud carried a lot of Victorian assumptions into his theory. He left a huge and complicated legacy which needs to be examined and picked through with care. My aim in these reviews is not to endorse his opinions but to summarise his writings, adding my own thoughts and comments as they arise.

***

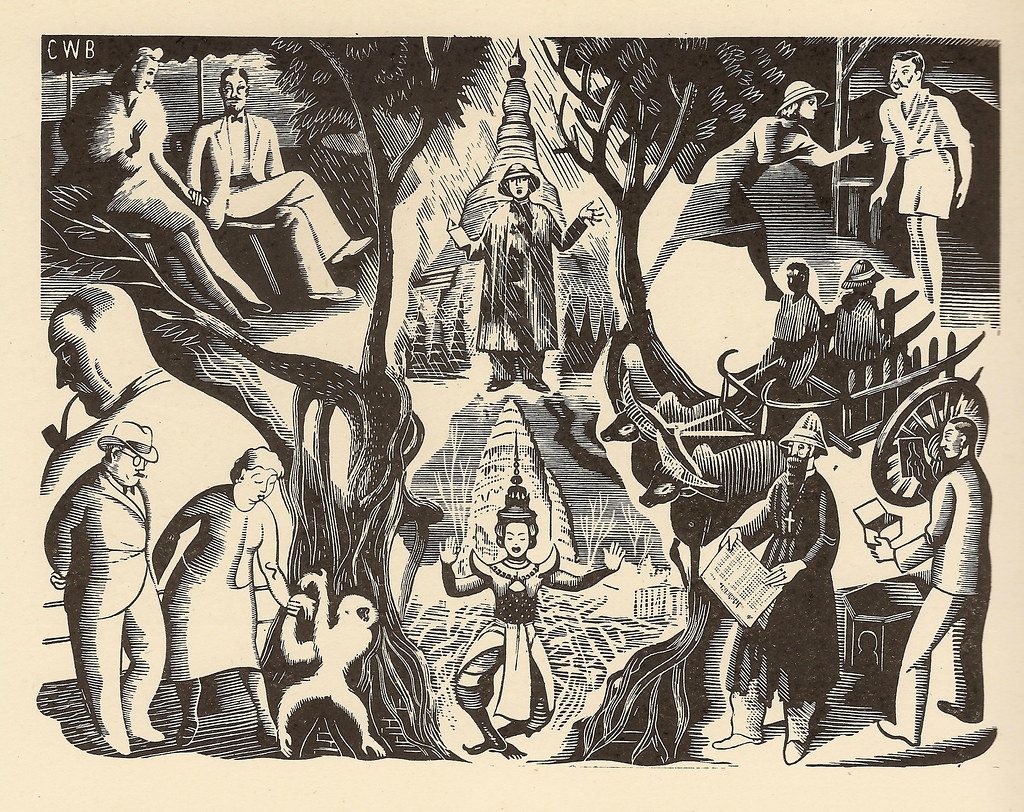

Civilisation and Its Discontents might more accurately be titled Why Civilisation Makes Us Unhappy. Freud suggests that civilisation is built on the renunciation of sexual and aggressive drives but that, although this benefits wider society, it often comes at the expense of anxiety and guilt i.e. mental illness, for us as individuals.

Many of the articles and books I’ve read about Freud claim that this was his single most influential book.

Civilisation and Its Discontents is a good example of Freud’s lifelong interest in the Big Questions of society – religion, morality, art and so on. His attempts at explaining the origins of society in Totem and Taboo (1914) and Moses and Monotheism (1939) were heavily criticised at the time and have been generally discredited since. His attack on Christianity in The Future of an Illusion (1927) doesn’t address (or invent) historical events in the same way as Totem and Moses does and so hasn’t dated so badly. It’s more an analysis of the psychological underpinnings of organised religion and so retains some force – although it has been superseded by thousands of later writers, commentators, utopians and revolutionaries, also seeking to abolish religious belief, so it’s just one polemic in a very crowded field.

By comparison with those other books, Civilisation and Its Discontents (although it kicks off with yet another dig at religious belief) is built on stronger foundations. Its central thesis that repression of our baser instincts is simultaneously the basis of a ‘civilised’ society and the source of many problems and mental illnesses suffered by its civilised citizens. This is an intuitively plausible argument which the passage of time has done nothing to discredit, which is why many critics reckon it might have been Freud’s single most influential book: its message that modern society makes us ill probably reached a far wider audience than any of his more theoretical or therapeutic works.

1.

Freud opens with a reference to his essay The Future of an Illusion, his most sustained, full-frontal attack on the psychological bases of religious belief. Freud replies to a critic who had written to say that Future failed to take into account genuinely spiritual feelings, in particular the ‘oceanic feeling’ of which the religious speak (as did Freud’s renegade follower, C.G. Jung).

Freud explains that this feeling is a relic, left after the realistic ego grew up, of a person’s infantile narcissism and sense of oneness with the world. For Freud religious belief begins in the infant’s sense of helplessness and need for parental protection, a feeling which is reborn and accentuated in the adult by their nervous awareness of the countless risks and dangers of human existence.

2.

Life is cruel. Human beings, endowed with memory to remember the past and reason enough to foresee the disasters of the future, need protection from both. There are three ways of escaping reality:

- Defence mechanisms, such as religion.

- Substitute satisfactions and sublimations of hopes and fears – Art.

- Intoxicants to extinguish consciousness.

What is the purpose of life? Well, who knows. But when you examine the way people actually behave – and not what they say – it is clear that most people live life in the pursuit of happiness. This happiness is threatened by three things:

- The decay and dissolution of the body.

- The destructiveness of the outside world.

- Our difficult relations with other people.

So how can we escape this dreadful predicament?

- hedonism? (full of risks and danger)

- art? (limited to the percipient few)

- intoxicants? (ultimately self-destructive)

- Eastern quietism? (brings only mild contentment, not happiness)

- hermetic isolation? (you go mad)

- delusions and mental illness? (as in psychotics and paranoiacs)

- mass delusions? (for example, religion)

- love, which may be the source of our greatest gratifications? (but oh how exposed and vulnerable we are to its sudden withdrawal)

- the enjoyment of beauty? (fickle and easily destroyed)

There are maybe three psychological types, who will each tackle these problems differently:

- The Erotic Man who wants love and sexual satisfaction.

- The Narcissist who tries to take control of the world in his own mental pleasures.

- The Man of Action who seeks to change the world.

But there is one complete worldview which seeks to tackle all of these threats to our wellbeing – Religion. Religion tackles the vulnerability of human beings by:

- depressing the value of life in this world

- drawing its followers into an unreal view of the world, similar to mass delusion

- fixing them in psychical infantilism

3.

So, it’s 1930. We are all discontented with civilisation. Why? Because in rising to a civilised level we have been forced to renounce many instinctual pleasures. A glance at many primitive peoples, for example, Australian aborigines, seems to show a people at one with life. By contrast, psychoanalysis has shown the terrible price in neurosis and nervous disease paid by ‘civilised’ people for the benefits of civilisation. A general disappointment with the early promises to improve life made by science and technology hasn’t improved things. So what are the salient features of this civilisation we are so unhappy with?

- technology and the exploitation of nature

- the creation of order and beauty

- higher mental achievements, for example, religion, art and science

- the ordering of human affairs via Justice and the Law

On the level of the individual citizen, civilisation is a process which results in:

- character-formation

- the sublimation of the instincts into ‘higher’ cultural achievements

- the renunciation of instinct

4.

The development of civilisation is like the growth of an individual. Savage men are driven to compete for a wife/sex object. One strong man comes to rule the horde. Then the sons rise up and kill the Father. Genital love is the motor in the formation of the Family. Aim-inhibited love leads to friendship and camaraderies, useful for uniting the group and forming bonds between them. Once set on this path, Man is moved to sublimate his basic sex-drive into more complicated psychic and social structures. As society is built up it exerts tighter control on the individual’s potentially anarchic sexuality, corralling it and narrowing it down to focus on heterosexual pairing. Even that restricted arena of expression mustn’t come about before a rigorous series of rituals have been carried out.

So much for libido and sex drive. Are there other reasons for the unhappiness created by civilisation?

5.

Yes. Human beings are violent. The Biblical injunction to love your neighbour is only necessary because there is such a violent urge in all of us to rape, torture, exploit and mutilate our neighbour. Society uses every means at its disposal to rearrange libido so as to secure social acquiescence. One obvious way is via aim-inhibited libido, libido which is rerouted into either generalised affection (for your dog or children or old people) or into friendship, rerouted libido which vastly expand the ties of family into society.

Civilisation has to use its utmost efforts in order to set limits to man’s aggressive instincts and to hold the manifestations of them in check by psychical reaction formations. Hence, therefore, the use of methods designed to incite people into identifications and aim-inhibited relationships of ‘love’, hence the restriction upon sexual life, and hence, too, the ego-ideal’s commandment to love one’s neighbour as oneself – a commandment which is justified by the fact that nothing runs so strongly counter to the original nature of man.

(Pelican Freud Library, volume 12, page 303)

The communists say that men were originally peaceable and equal but that the institution of private property has corrupted them. Do away with private property and everything will be alright. Freud laughs. On the contrary, all societies are bound together by what they exclude, by their ability to project the natural aggression of their members outwards onto outsiders.

In this respect the Jewish people, scattered everywhere, have rendered most useful services to the civilisations who were their hosts. (volume 12, page 305)

A newly insurgent dream of Germanic world domination has inevitably raised the oldest scapegoat upon which to focus its anger – the Jew. And the communist utopia in Russia turns out to call for an entire class to anathematise, the bourgeoisie (although, at this period, the direst fate was being meted out to the wealthier peasants, known as kulaks.)

In order to become civilised, man has to give up these two elements: unbridled sexual satisfaction and the expression of aggression. Primitive man expressed these easily and was happy. He also died young. Civilised man has exchanged happiness for security. We live long lives with a lot of frustration and misery in them.

6.

Section 6 is a complicated defence of Freud’s theory of the death instinct or Thanatos. Originally Freud posited just two psychic classes, ego-instincts and object-instincts. The idea of narcissism, first developed in an essay of 1914, complicated matters and by 1920 Freud had developed a new fundamental opposition, that between Eros and the death drive, between instincts which seek to unify, to bind (in a primitive way with the breast, with food; later with a sex-object; in a sublimated form with friends or comrades, via aim-inhibited libido) and instincts which seek to break psychic energy down into smaller units, ultimately to death.

In practice our instincts always appear in some combination. On the personal level libido accompanied with aggression is sadism; the death drive comes to the aid of group psychology and aim-inhibited libido by being deflected outwards onto strangers and enemies. Aggression thwarted is turned inwards as masochism or self-punishment or suicide. Despite opposition and scepticism to these ideas, even within analytic circles:

I adopt the standpoint, therefore, that the inclination to aggression is an original, self-subsisting instinctual disposition in man, and that it constitutes the greatest impediment to civilisation. (12: 313)

Civilisation is a process in the services of Eros, whose purpose is to combine single human individuals, and after that families, then races, peoples and nations, into one great unity, the unity of mankind. These collections of men are libidinally bound to each other. Necessity alone, the advantages of work in common, will not hold them together. But man’s natural aggressive instinct, the hostility of each against all and of all against each, opposes this programme of civilisation. This aggressive instinct is the derivative and the main representative of the death instinct which we have found alongside Eros and which shares world dominion with it. Thus the evolution of civilisation represents a struggle between Eros and Death, between the instinct of life and the instinct of destruction, as it works itself out in the human species. This struggle is what all life essentially consists of and it is this battle of giants that our nursemaids try to distract us from with their lullaby about Heaven. (12: 314)

7.

So how is this aggression controlled in the individual? Through the superego. By returning it in upon itself, by setting a part of itself aside, the ego is able to satisfy upon itself the aggressive wishes it would like to impose on others – Freud calls this mental agency the conscience and the emotional affect it produces in us is guilt. The superego is the watch-dog of civilisation planted inside the head of each of us.

Guilt is the fear of the loss of love, its primal source the withdrawal of parental love. In its simplest form, if you do something bad you are anxious that you will be found out and that love will be withdrawn from you, the love of your parents or of the community at large. So you can still do wrong but will strive not to be found out.

In the more sophisticated form, you develop a full superego based on childish experiences and anxieties. Now you feel guilty even if no-one finds out or can find out what you’ve done – because someone does know; your conscience knows. What’s more, it knows about things you haven’t even done but have fantasised about doing; and it knows about things you’ve fantasised about doing and repressed so deeply you don’t even remember them. Since everyone has the same Oedipal fantasies, everyone suffers a greater or lesser sense of guilt.

More: the superego is fiercest in those who set out to please it most; the more you try to please it in every way, the more demanding the superego becomes. Hence the pathological saint. And if bad luck from the external world does actually befall you, this only provides the punishing superego with more opportunities to punish you for being such a loser. Hence, Freud declares, with the confidence of an unbelieving Jew, the characteristics of the Jewish race, in that the more calamities overtook it, the more they blamed themselves.

More: there is an original substratum of guilt laid down in all of us due to archaic vestiges of the primal Parricide, which is bequeathed to each of us at birth. Its traces are reawakened by naughty things we do, which introduces us to fear of punishment (withdrawal of love); and further reinforced by the introjection of that fear/aggression in a superego. The more we renounce our instincts, the more the superego is given energy to punish us, to demand more. Therefore, insofar as civilisation is defined as the renunciation of instinct, it must inevitably lead to an increase in guilt. Civilisation, by its very nature, reinforces the superego in all of us, and the superego is the punishing principle. Civilisation must make everyone feel guilty.

8.

So, to recap: The price we pay for civilisation and security is the loss of happiness through instinctual renunciation and an accompanying increase in personal guilt.

Freud goes on to speculate that maybe guilt is the product not of libidinal wishes but only of repressed aggressive wishes. So neurotic symptoms are the result of the libido being repressed; when aggression is repressed it reactivates ancient feelings of remorse (for murders, real or imaginary) and guilt i.e. the aggression is rechannelled, via the superego, against the repressing ego, in the form of demands for more obeisance and penitence.

Freud draws the analogy between the development of an individual and the development of civilisation. In the latter, also, a superego, an ego-ideal, is created in the form of a strong leader – Moses, Jesus et al. Just as the oedipal boy unconsciously wishes his authoritative father dead but then suffers remorse and guilt at these buried feelings, so the Jews and Christians wanted their insufferably strict leaders dead and then, in fact, killed them. And just as the individual superego – in the latency period – sets up an idealised version of the dead leader’s injunctions and punishes followers for not attaining them, so entire peoples feel guilt and remorse at the primal murder they’ve committed, set up idealised versions of the murdered Father (of Moses who talked to God, of Jesus who IS God) and punish themselves for not living up to these impossibly high ethical standards.

Over and above the vague sense of guilt or malaise whose origin Freud has explained, there are the specific injunctions of the superego. In individual patients, modern therapy often consists in softening the impossibly strict demands made on them by their own superegos, demands which result in unhappiness and illness.

In society as a whole, the same is true. Our society makes impossible demands on people. Freud singles out the injunction to love your neighbour as yourself as a prime example. It is a fine specimen of the highest ethical ideal a society can rise to, but its very impossibility leads to unhappiness among the many people who try to live up to it, fail, and then punish themselves.

Freud dryly remarks that he thinks maybe a real change in the relations of people and their possessions, a genuine redistribution of wealth – in other words communism – would be more likely to produce ethical improvement than religion’s insistence on demanding the impossible.

Credit

The history of the translation of Freud’s many works into English forms a complicated subject in its own right. Civilisation and Its Discontents was translated into English in 1961 as part of The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Quotes in this blog post are from the version which was included in Volume 12 of the Pelican Freud Library, ‘Civilisation, Society and Religion’, published in 1985.