Extraordinary the impact this book had. First a series of five movies 1968-73, then a TV series (1974-5). In recent years the movie franchise rebooted, first with Tim Burton’s 2001 version and then again, with a new sequence of films (Rise of the Planet of the Apes 2011, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes 2014, War for the Planet of the Apes in 2017). Just these three movies alone have grossed over $2 billion.

And ever since the original movie there’s been an impressive array of comic books and graphic novels, computer games, toys and theme park rides (!).

Why is the story so powerful? What is its hold?

Frame story – Jinn and Phyllis

It is thousands of years in the future. The planets have been colonised and interstellar travel is common. Many travel on business in fast rockets. Jinn and Phyllis are more like tourists in space, dallying in a sealed sphere whose sails can be set larger or smaller to catch the solar winds coming from the stars and drift around the universe. One day they see an object flying by, change course to collect it, and find it is a message in a bottle, a glass bottle. Inside it are sheafs of paper with a long narrative scrawled on them.

Jinn reads out this narrative which makes up the main body of the text.

The narrative of Ulysse Mérou

This text is written by the journalist Ulysse Mérou in the year 2500. He has been invited to join the space expedition led by Professor Antelle, and accompanied by his assistant Arthur Levain, which is travelling to the nearest star, the mega-star Betelgeuse.

(Although published in 1963 everything about the space trip reminds me of H.G. Wells. We are not told anything about the design of the ship or nature of the propulsion system (always the snag in space travel sci-fi). Antelle is travelling in a ship he designed and built himself, almost as if he’d done it in a shed at the bottom of the garden. And they choose Mérou to accompany them because he is good at chess. In other words the whole story has the charming amateurism of Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger stories or Well’s earlier science fantasies, many light years remote from the reality of the vast army of technicians backed up by the state, which would be required just to take a man to the moon later the same decade.)

It takes two years to travel to Betelgeuse, one year to accelerate to nearly the speed of light, a few days travelling at phenomenal speed, then a year slowing back down. As any reader of science fiction should have picked up, the closer to the speed of light you travel, the more time slows down relative to objects and people travelling at normal speeds i.e. people on Earth. Thus, while the trip to Betelgeuse will only take the trio two years, something like 350 years will have passed on Earth. Everyone they know and everything they know will have died and changed utterly.

Arrival on Soror

When they get to Betelgeuse, they discover there are four planets circling the super-star, and one of them, surprise surprise, is the same distance from the big star as Earth from the sun, and appears to have the same gravity and atmosphere as our home planet.

Our trio takes to one of the space ‘launches’ built into the main spaceship (no description whatsoever of what it looks like or how it works) and shuttle down to the planet, skimming over what appear to be cities, with buildings laid out along streets, before landing in a clearing in a ‘jungle’.

Once again, it comes as no surprise that the air on the planet is breathable – made of oxygen and nitrogen pretty much the same ratio as on Earth.

(This is as wildly improbable as when Cavor and Bedford unscrew the door of their sphere in First Men In The Moon and discover that the moon has a breathable atmosphere, if rather thin. Monkey Planet is not hard science fiction of the heavily factual Arthur C. Clarke variety. We are more in the realm of science fable.)

They christen the planet Soror, sister to our Earth.

So the three Frenchmen get out, stretch, wander around, see birds flying overhead, are struck by how similar the trees and flower are and discover a waterfall, so they strip off and swim and wash. It feels like a film already. You can imagine the tropical sunlight dappling through exotic leaves onto the sun-kissed bodies of our three hunky heroes.

Nova

At which point there is a Robinson Crusoe moment, as they spot a human footprint in the sand. A woman’s footprint by the shape of it. And then she appears.

Being a man, Boulle casts this first alien human as a woman, and being a Frenchman he imagines her a naked woman – and the whole thing veers towards the crudest pulp sci-fi when he describes her as a golden-skinned, physically perfect woman, a goddess perfect in form and feature etc.

I shall never forget the impression her appearance made on me. I held my breath at the marvellous beauty of this creature from Soror, who revealed herself to us, dripping with spray, illuminated by the blood-red beams of Betelgeuse. it was a woman – a young girl, rather, unless was a goddess. She boldly asserted her femininity in the light of this monstrous sun, completely naked and without any ornament other than her hair which hung down to her shoulders…Standing upright, leaning forwards, her breasts thrust out towards us, her arms raised slightly backwards in the attitude of a diver…It was plain to see that the woman, who stood motionless on the ledge like a statue on a pedestal, possessed the most perfect body that could be conceived on earth. (p.23)

Mérou christens her Nova, and she strikes this reader as being the oldest pulp fiction trope in the world – the pure, innocent, scantily-dressed (in fact, naked) damsel, who will, later on in the book, be threatened by great big hairy apes – with only our gallant narrator to protect her.

But, puzzlingly, it quickly becomes clear that Nova cannot talk and is scared when they laugh or talk. She can only make quick grunting noises, almost like an ape. In fact the three Frenchmen’s smiles and laughter scare her off.

Next day they go frolic in the waterfall again, and the perfect woman returns, with a man, fine figured but also mute. More mute humans assemble. When our trio put on their clothes, the humans recoil in fear and disgust. Walking back to the spaceship our heroes are attacked from all sides by quite a crowd of humanoids, as many as a hundred, who rip and tear their clothes off. Then the mob of animal-humans proceeds to break into the space launch and destroy, rip and tear apart everything they can get their hands on. But not like human vandals working systematically. More like animals, tearing and worrying and biting at something they don’t understand.

Destruction of the ship

Having trashed the ship, the savage humans drag our heroes back to their village. Except it doesn’t even have huts, is more a random scattering of makeshift shelters, a few branches leaning against trees, just as the great apes make. Nova, as you might have guessed, has formed a bond with our gallant narrator and comes and snuggles up against him, again more like an animal seeking warmth than an intelligent partner.

The manhunt

The next morning they are all woken by alarming sounds, ululations and shouts, yes shouts, language, as of humans. The humanoids run round in a panic and set off in the opposite direction, Mérou fleeing with them.

He begins to realise the people coming behind are beaters and the humanoids are being driven – and then he hears shots, gunshots. They are being driven towards hunters out for some sport.

Mérou comes to a break in the tall grass and is flabbergasted to see an enormous gorilla wearing clothes and wielding a shot gun, taking shots at the terrified humans as they emerge from the long grass into this break.

Mérou watches a human burst out of the grass into the open area and the gorilla carefully take aim and shoot him. He hands his gun to a smaller chimpanzee, behind him, also dressed, who recharges it with cartridges and returns it to the gorilla. Mérou’s head is spinning at what this seems to say about the planet they’ve arrived on – the traditional roles of ape and man appear to have been completely reversed.

Mérou waits till the gorilla fires (hitting another human) and hands the gun over to be reloaded, and then takes his chance. He runs across the break of open ground and into the long grass on the other side. But it is only to stumble into a trap of mesh netting which scoops him and other humans up into a huge struggling bundle, waiting for the master apes to come.

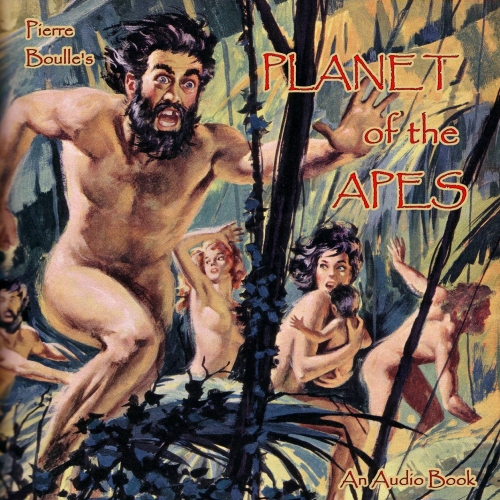

Cover of an audiobook of Monkey Planet which captures the terror of the hunt, artwork by Harry Schaare (1964)

The human laboratory

Mérou is thrown into a cage along with other naked humans. He watches in disbelief as the gorillas return from the hunt and lay out the killed humans neatly and artistically, smoothing down ruffled hair as a human hunter would smooth down an animal’s fur or feathers, arranging the corpses in aesthetic poses.

Mérou is still reeling from the way the gorillas are wearing clothes, normal clothes, hunting clothes. One sneezes and brings a handkerchief out of his breeches to blow his nose. The cages are on wheels and are pulled by a sort of tractor back to a sort of hunting lodge where the female gorillas are waiting, wearing dresses and hats. A photographer turns up and snaps the hunter gorillas posing by their kills, with their proud womenfolk on their arms. Mérou feels as if he’s going mad.

Finally the hunters clamber onto some of the tractors, and along with those pulling cages full of human captives, they set off some distance to arrive at a town. Mérou observes a grocer pulling down his blind as he opens up shop. They have motor cars, banks, shops. It all sounds like a French provincial town except… populated by apes!

Mérou is unloaded at a hospital-like building and ushered down a corridor into a cage, one of many containing single or pairs of humans bedded on straw. Over the weeks it becomes clear that they are lab animals, kept to be experimented on. The experiments are mostly behavioural i.e. the Pavlov experiment of ringing a bell and offering food to make the animals salivate, eventually just ringing the bell to produce the same reaction.

The warders – two gorillas named Zoram and Zanam – hang fruit from the roof of a cage, then put four cubes in the cage. Only Mérou has the intelligence to realise that if you stack the four boxes on top of each other you can simply step up them and reclaim the fruit. The other humans watch him with complete incomprehension. By now he has realised that the humans really are animals without the slightest flicker of intelligence, let alone intellectual ability.

Then there is observation of mating rituals. The apes place male and female subjects in the same cage and observe their mating ritual – which amounts to the male circling round the female with ornate steps… before eventually pouncing on his hypnotised prey.

Mérou swears he won’t sink to the same level when they place Nova in his cage (yes, Nova has miraculously survived the manhunt and was thrown into a tractor cage and was transported to the same ‘hospital’ and has, by happy coincidence, now been thrown into Mérou’s cage). But when he fails to perform and they take her away and replace her with an old crone, and he sees another hulking male preparing to mate with Nova, Mérou changes his mind, makes a fuss and Nova is restored to him, at which point… well… when on Soror, do as the Sororians do.

(The fact that Mérou mates with Nova fulfils the soft porn, pulpy sexual promise which has been latent in the story ever since the trio sighted her splendid naked body by the waterfall. It is as inevitable as falling off a log.)

(Incidentally, Mérou saw the body of the professor’s assistant, Arthur Levain, stretched out in the array of ‘kill’ at the hunting lodge. Of the professor, he has seen no sign.)

Befriending Zira

But it isn’t just the gorillas who conduct these experiments. A female chimpanzee attends with a pen and notebook. Over the course of her visits, Mérou manages to impress on her his intelligence, first of all parroting back to her some of the simian language, which he has begun to pick up. But then, in a decisive move, Mérou seizes her pen and notebook and draws a sequence of geometric shapes, hands it back to her and she draws some more, and gives it back to him who draws some more.

She is deeply shaken, but begins – when the gorillas’ attention is distracted by other prisoners – to talk to him. She is Zira. Her fiancé is Cornelius. She poo-poos the pompous orangutan, Dr Zaius, who has come to visit the lab several times, obviously the head of the institute who orders around the gorillas and ignores Zira’s comments.

Zira lends Mérou some books which he hides and reads at night. He is making progress in the simian language and is nearly fluent. He learns that Soror has only one world government, divided into three chambers, one each for the chimps, orangs and gorillas. The gorillas are still the most physical among the apes, a legacy from the days when they ruled, and they’re the ones who implement and carry out discoveries. The orangutans are the ’embodiment of science’ and wisdom except that, in Zira’s opinion, it is a hidebound, out-of-date science. According to Zira all the important discoveries have been made by the chimps.

(We know from our own planet that the human race is split into thousands of cultures and languages, with wildly different levels of technical achievement; and yet so many science fiction stories fly in the face of all this evidence and land on planets where this is just one World Government, or one Ruler, and one language, which the human arrivals quickly pick up. it’s one of the most flagrant ways in which science fiction is so disappointingly simple-minded and simplistic.)

Zira gets permission one day to take Mérou for a walk (obviously on the end of a leash and naked – he is a pet after all) to a park where she introduces him to her fiancé, Cornelius. by this stage Mérou has used drawings to persuade Zira that he is in fact from a different planet in a different solar system, and now his explanation in fluent simian persuades Cornelius as well.

But, the chimps explain, the orangutans are resistant to all change, they still teach that Soror is the centre of the universe and Zaius refuses to accept that Mérou is anything more than a performing pet. And Mérou is in danger. They have extensive labs in which they conduct experiments on the brains of humans, sometimes while they’re conscious – something to be avoided.

Mérou addresses the conference and wins his freedom

Cornelius and Zira come up with a plan: there is soon to be a scientific conference. Dr Zaius wants to present Mérou as an example of man’s mimetic abilities, as a kind of performing pet. There will be an immense convocation of scientists, and journalists, and members of the public. It will be a perfect opportunity for Mérou to step forward and address public opinion directly.

And this is exactly what he does. Mérou is brought onstage as a specimen for Zaius to put through his paces but astonishes everyone by taking the microphone, bowing, making polite reference to the chair of the meeting and proceeding to make a long, pompous and respectful speech to the members of the academy explaining that he is an astronaut from the planet Earth (drawing a map of Earth’s location). Now not even Zaius can deny the fact that Mérou is an intelligent, autonomous human being, something which defies all their science.

This understandably causes an uproar and, over the next few days, Mérou is released from his captivity, allowed to get dressed and meets other scientists to discuss his story.

Mérou can now be taken on a tour of simian society and discovers it to be in almost every respect identical to human: there are theatres, athletic games and sports contests. He is taken to the zoo and, unwisely, asks to see the human cages. There he is horrified to discover Professor Antelle, naked and dishevelled like the other human-animals, begging for food from the child apes who throw bits of cake through the bars.

Mérou begs for a personal meeting with the professor. Cornelius uses Mérou’s new-found celebrity to persuade the director of the zoo to allow Mérou a meeting with the professor, but we are horrified to see that Antelle really has descended to the level of the animals. There is nothing behind his eyes. There isn’t a flicker of recognition as Mérou talks to him. In fact this section ends, hauntingly, with Antelle lifting his head and letting out a prolonged animal howl.

The archaeological site on the other side of the world

Mérou now comes to learn more about Cornelius’s research and to share his investigation into the origins of ape society. The most salient fact about it is the way it appears to have stagnated at the same technological level for centuries, indeed millennia. Ape records stretch back some 10,000 years but then there is a complete blank. Mérou himself has spent hours speculating about how the situation came about – why are the apes in charge and humans voiceless, unintelligent animals? Is it fluke? Accident? At some point of evolution could it have gone either way and, on Earth went one way, and here went another?

Their speculations are brought to a climax by two incidents:

1. He is invited to an archaeological site on the other side of the world. (He flies there in a jet, a detail which is swiftly glossed over but gives you an indication of how different Boulle’s vision of ape society is from the ape society depicted in all the movies: in the movies it is a society reduced to medieval level, everyone rides on horses, the townships are little more than mud huts; in Boulle’s vision, ape society is exactly like human society, with cars driving along busy city streets lined with shops and, as here, jet planes taking off from airports.) Cornelius’s colleagues are excavating a settlement which appears to date from before the apes’ earliest records of 10,000 years ago. And they have found something seismic – a doll, a human doll, which is wearing not only the vestiges of clothes, but which, when pressed, says the word ‘Papa’. It is a fragment, but a fragment which confirms Cornelius and Mérou’s suspicions. The humans came first.

2. The second incident is when Cornelius takes Mérou to see the brain experiments the apes conduct on humans. The first set of these are genuinely horrifying, sticking electrodes in human brains to observe the flexing of various muscles or to bring on epileptic fits. This sequence is the clearest example of the way Boulle uses his fable to argue against cruelty to animals. Mérou is sickened and eventually cries out in anger at the torture he’s seeing his fellow humans subjected to.

The voices of history

But then there is an extraordinary scene where Cornelius takes us to nother room where electrodes have been applied to the brains of two humans. This operation makes the male patient talk, although only broken fragments of phrases he’s obviously overheard in the lab and cages. Still, it is empirical proof that humans can talk.

But it’s the woman specimen who is the real prize. Applying electrodes to her brain unlocks the collective memory of the race.

In a wildly unscientific and implausible manner which is, nonetheless, fantastically imaginatively powerful, through this woman as via a clairvoyant, we hear the voices of the humans from that long-ago era, before 10,000 years ago, who one by one record the fateful sequence of events which led to the downfall of mankind and the rise of the apes.

Various voices dramatise and comment on the way the human race became lazy and unmotivated, while the apes they had trained to be servants banded together, learned to communicate and speak simple phrases, were heard muttering together at nights. A woman tearfully admits she has handed over her house to the gorilla who used to be the maid and cleaner, and has come to the ‘camp’ of humans outside the city. Another laments the passivity and lassitude of humans. A final one describes in terror hearing the approach of a hunt of apes who don’t even bother to chase them with guns any more, but simply use whips! The woman’s story ends.

Cornelius and Mérou look at each other. So, it is as they thought. Ape culture has stayed more or less the same for millennia because it is a copy of the human culture which preceded it.

The moral of the story

If there is a moral to the story it is here, and it is about the peril to the human race of losing its drive and purpose and will to live. This kind of thing routinely crops up in mid-century science fiction although it is, I think, incomprehensible to us now. I think it was a warning frequently issued by ‘prophets’ in the West (America and Europe) against succumbing to materialism, consumerism and losing our souls, losing our thirst for the higher, intellectual life.

In fact Planet of the Apes taps into the anxiety about the Degeneration of the West which goes back at least as far Max Nordau’s bestseller, titled simply Degeneration, which was published in 1892 and which took French art and morality as demonstrating the degeneration and decline of the West. The notion that humanity got slaves (in this case, apes) to do their work for them, and became too lazy to maintain their place at the top of the tree, has a long lineage.

As far as I can see, the West has utterly succumbed to consumer capitalism, everyone in the West is addicted to their phone and its apps and gadgets and wastes hours on endless social mediatisation. And yet the apocalypse has not followed: art is still created, more books and poems and plays than ever before are produced.

The ‘collapse of civilisation’ which Boulle appears to be warning about never came.

Nova has a baby and they escape

Several scenes earlier Zira had told Mérou that Nova is pregnant with his child.

Other episodes intervene, such as the flight to the archaeological site, seeing the vivisection experiments on the humans, trying to get through to Professor Antelle whose purpose is to make the nine months fly past until Nova has her baby. Mérou christens the baby boy Sirius.

At this point things become really dangerous for Mérou, Nova and the baby. Zira and Cornelius tell him that Dr Zaius and the orangutans are winning the argument at a senior level. They are arguing that Mérou and Sirius represent an existential threat to ape rule. Already the humans in the cages where Mérou was first kept are noticeably respectful of him when he makes occasional visits back there, despite wearing clothes, something which made them shriek with horror when they first saw him. As if he is in the early stages of becoming their leader.

Similarly, Nova, after all this time in contact with Mérou, has learned to make a few sounds and the first tentative attempts to smile, to make facial expressions, something which was unthinkable when we first met her.

And, as the months go past, the infant Sirius begins to make articulate noise, not just animal cries. Cornelius warns Mérou that the orangs are persuading the gorillas to eliminate all three of them, carry out brain experiments on them, remove their frontal lobes, anything to eliminate the threat.

The pace of the narrative speeds up here, maybe because it’s becoming so wildly implausible, and Mérou writes increasingly in the present tense, drawing the reader directly into the fast-moving sequence of events.

Cornelius now tells Mérou that the apes are about to launch a manned probe into space, literally ‘manned’ with a man, a woman and a child, who will be trained to carry out basic tasks, so the apes can study the impact of them of space radiation, weightlessness etc.

Cornelius knows the chimpanzee running the programme. He’s persuaded him to do a switch.

And so it unfolds. In half a page Mérou describes how he, Nova and Sirius are smuggled aboard the ape probe, how it is launched into space, how he is able to navigate it to the master spaceship in which the three men originally travelled from Earth over a year earlier, manoeuvres it into the ‘bay’ from which the ‘launch’ had departed, the air doors closed, robots take over, and then he steers the spaceship out of orbit round Soror, and back to Earth at nearly light speed.

The punchline

And here comes the part of the book which, if you’re open and receptive and young enough, packs a killer punch.

Mérou steers the spaceship into earth orbit, round the earth towards Europe, then down through the clouds towards France, and finally brings it gently to land on the airfield at Orly airport.

Turns the engines off and sits in silence. Then all three clamber out and watch as a fire engine heads across the runway towards this unexpected arrival.

As explained at the start of the book, and reprised on the flight home, travelling at near light speeds means that while only two years pass for Mérou, Nova and Sirius, something like seven hundred years have passed back on Earth. Given this immense passage of time Mérou is surprised there seem to have been so few changes. As they flew over Paris he noticed the Eiffel Tower was still there. Now he notices that the airfield is in fact a bit rusty and dotted with patches of grass, as if rundown.

And he’s surprised that the fire engine that comes wailing towards them is a model familiar from his own time. Has nothing changed? Surprising.

As the engine draws up fifty yards from them the setting sun is reflected in its windscreen so Mérou can only dimly make out the two figures inside. They climb down with their backs towards him, also obscured by the long grass here at the edge of the airstrip. Finally one emerges from the long grass. Nova screams, picks up Sirius and sets off running back towards the ship.

The fireman is… a gorilla!

In a flash Mérou – and the reader – grasps the situation: here, as on Soror, humans cultivated the apes, made them servants, taught them the basics of language, then got lazier and more dependent on their servants who, at some stage, overthrew their human masters, reducing them to voiceless slaves, though themselves proving incapable of improving on human technology – this terrible fate has happened on Earth, too!

Frame story Jinn and Phyllis

Well. This is how the narrative in a bottle ends and Jinn stops reading to Phyllis. They are both silent for a long time. Then they both break out in agreement. Humans! Capable of speech and thought! It was a good yarn but, on this point, too far-fetched.

Humans talking! What a ridiculous idea. And Jinn uses his four hands to trim the sails of their cosy little space-sphere, and Phyllis applies some make-up to her cute little chimpanzee muzzle. We now realise that they, too, are apes. Mérou’s narrative was from the last intelligent human on either planet. The triumph of the apes is complete.

Reasons for success

I think it is the thoroughness of the fable which makes it so enduring. Boulle has really thought through the implications of his reversal, of the world turned upside down.

Details of the spaceship and its advanced rockets are trivia compared with the archetypal power of the story. What if… What if the entire human race is overthrown and reduced to a state, not even of savagery, but lower than that, dragged right back to brute animality?

I think the fable addresses a deep anxiety among thinking humans that the condition of reason and intellect and mentation are so fragile and provisional. And at the same time sparks the familiar thrill which apparently resonates with so many readers and cinema goers, at witnessing the overthrow and end of the human race. In my (Freudian) interpretation, reflecting a profound, mostly unconscious death wish, which many many people thrill to see depicted in gruesome detail on the screen and then, primitive urges sated, return to our humdrum workaday lives.

Style and worldview

It has gone down in pop culture lore that the first words the astronaut hero of the first Planet of the Apes movie (played by Charlton Heston) utters to an ape is, ‘Take your stinking paws off me you damn dirty ape!’

Whereas the first words Ulysse Mérou addresses to an ape, are spoken to one of the gorilla wardens feeding him and supervising him once he has arrived at the human laboratory-cages: ‘How do you do? I am a man from Earth. I’ve had a long journey.’

Obviously, one is a movie, an American movie, and the other is a novel, a French novel, but the two moments can be taken as symbolic of the differing worldviews of the two cultural artefacts. The French novel is full of high-flown sentiments about the nature of humanity and the human spirit. Like Olaf Stapledon back in the 1930s, Boulle considers human intelligence to be a kind of peak of creation, something of special importance and significance, hence his shock at finding the humans mute animals is all the greater. His sense of the unparalleled importance of humanity is tied to his sense of his own importance, self-love, a concept so French that we have imported their phrase for it – amour propre – ‘a sense of one’s own worth; self-respect’. This is wryly expressed in the scene where he finds himself having to copy the mating ritual of the animal-humans:

Yes, I, one of the kings of creation, started circling round my beauty; I, the ultimate product of millenary evolution, I, a man… I, Ulysse Mérou, embarked like a peacock round the gorgeous Nova. (p.76)

Nowadays, I take it there is a much more realistic and widespread feeling that humans are not particularly important, that plenty of other species turn out to be ‘intelligent’ and communicate among themselves, and many people share my view that humans are, in fact, a kind of pestilential plague on the planet, which we are quite obviously destroying.

But this book, from 55 years ago, although it is about man’s fall into a bestial condition, nevertheless is full of rhetoric about the special, privileged position of intelligence in the universe, and is full of a very old-fashioned kind of triumphalist rhetoric about the ongoing march of intelligence.

Here is Cornelius arguing with Mérou, arguing that the rise of the apes was inevitable because they have a loftier destiny:

‘Believe me, the day will come when we shall surpass men in every field. It is not by accident, as you might imagine, that we have come to succeed him. This eventuality was inscribed in the normal course of evolution. Rational man having had his time, a superior being was bound to succeed him, preserve the essential results of his conquests and assimilate them during a period of apparent stagnation before soaring up to greater heights.’ (p.148)

The idea of a Great Chain of Being, a hierarchy of intelligence which you can imagine as a sort of ladder whose occupants become increasingly intelligent as you climb up it, is a basic element of the Renaissance worldview, going back through medieval texts, deriving from the systematising of late classical followers of Plato. In the Middle Ages it became the ladder which led up through the Natural World, to man, then the angels, then to God himself.

When science came along in the 19th century the idea of there being an up and a down to life on earth, of a forwards and upwards drive in evolution, was taken over by positivists and lingered long into twentieth century political, social and fictional rhetoric.

It’s gone now. It was associated with the notion of a hierarchy of races (wise whites at the top), of genders (wise men at the top), and class (the wise Oxbridge-educated at the top), all of which began to be questioned and undermined soon after Boulle’s book was published.

Also, in biology and evolution, there is now no sense at all that humans are somehow ‘superior’ to all other animals because (in the tired old trope) we produced a Shakespeare or a Mozart. Watch any David Attenborough nature documentary and you’ll see that biology, for some decades now, assumes that everything is highly evolved, where highly evolved means that the organism fits perfectly into the niche it occupies.

The notion that ‘evolution’ means some vague, half-religious drive ‘upwards’ towards greater and greater intelligence has been replaced by a notion of ‘evolution’ which is a computer-aided understanding of the myriad complexities of DNA and genetics, and how they act on organisms to ensure survival. There is no ‘onwards and upwards’. There is merely change and adaptation, and that change and adaptation has no innate moral or spiritual meaning whatsoever.

Thus reading Monkey Planet is, like reading most science fiction, not to be transported forwards into a plausible future, but the opposite – to travel backwards in time, to the completely outdated social and intellectual assumptions of the 1940s and 50s.

Related links

Other science fiction reviews

1888 Looking Backward 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy – Julian West wakes up in the year 2000 to discover a peaceful revolution has ushered in a society of state planning, equality and contentment

1890 News from Nowhere by William Morris – waking from a long sleep, William Guest is shown round a London transformed into villages of contented craftsmen

1895 The Time Machine by H.G. Wells – the unnamed inventor and time traveller tells his dinner party guests the story of his adventure among the Eloi and the Morlocks in the year 802,701

1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells – Edward Prendick is stranded on a remote island where he discovers the ‘owner’, Dr Gustave Moreau, is experimentally creating human-animal hybrids

1897 The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells – an embittered young scientist, Griffin, makes himself invisible, starting with comic capers in a Sussex village, and ending with demented murders

1898 The War of the Worlds – the Martians invade earth

1899 When The Sleeper Wakes/The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells – Graham awakes in the year 2100 to find himself at the centre of a revolution to overthrow the repressive society of the future

1899 A Story of the Days To Come by H.G. Wells – set in the same future London as The Sleeper Wakes, Denton and Elizabeth defy her wealthy family in order to marry, fall into poverty, and experience life as serfs in the Underground city run by the sinister Labour Corps

1901 The First Men in the Moon by H.G. Wells – Mr Bedford and Mr Cavor use the invention of ‘Cavorite’ to fly to the moon and discover the underground civilisation of the Selenites

1904 The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth by H.G. Wells – scientists invent a compound which makes plants, animals and humans grow to giant size, prompting giant humans to rebel against the ‘little people’

1905 With the Night Mail by Rudyard Kipling – it is 2000 and the narrator accompanies a GPO airship across the Atlantic

1906 In the Days of the Comet by H.G. Wells – a comet passes through earth’s atmosphere and brings about ‘the Great Change’, inaugurating an era of wisdom and fairness, as told by narrator Willie Leadford

1908 The War in the Air by H.G. Wells – Bert Smallways, a bicycle-repairman from Kent, gets caught up in the outbreak of the war in the air which brings Western civilisation to an end

1909 The Machine Stops by E.M. Foster – people of the future live in underground cells regulated by ‘the Machine’ until one of them rebels

1912 The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Professor Challenger leads an expedition to a plateau in the Amazon rainforest where prehistoric animals still exist

1912 As Easy as ABC by Rudyard Kipling – set in 2065 in a world characterised by isolation and privacy, forces from the ABC are sent to suppress an outbreak of ‘crowdism’

1913 The Horror of the Heights by Arthur Conan Doyle – airman Captain Joyce-Armstrong flies higher than anyone before him and discovers the upper atmosphere is inhabited by vast jellyfish-like monsters

1914 The World Set Free by H.G. Wells – A history of the future in which the devastation of an atomic war leads to the creation of a World Government, told via a number of characters who are central to the change

1918 The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs – a trilogy of pulp novellas in which all-American heroes battle ape-men and dinosaurs on a lost island in the Antarctic

1921 We by Evgeny Zamyatin – like everyone else in the dystopian future of OneState, D-503 lives life according to the Table of Hours, until I-330 wakens him to the truth

1925 Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov – a Moscow scientist transplants the testicles and pituitary gland of a dead tramp into the body of a stray dog, with disastrous consequences

1927 The Maracot Deep by Arthur Conan Doyle – a scientist, engineer and a hero are trying out a new bathysphere when the wire snaps and they hurtle to the bottom of the sea, there to discover…

1930 Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon – mind-boggling ‘history’ of the future of mankind over the next two billion years

1938 Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis – baddies Devine and Weston kidnap Ransom and take him in their spherical spaceship to Malacandra aka Mars,

1943 Perelandra (Voyage to Venus) by C.S. Lewis – Ransom is sent to Perelandra aka Venus, to prevent a second temptation by the Devil and the fall of the planet’s new young inhabitants

1945 That Hideous Strength: A Modern Fairy-Tale for Grown-ups by C.S. Lewis– Ransom assembles a motley crew to combat the rise of an evil corporation which is seeking to overthrow mankind

1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell – after a nuclear war, inhabitants of ruined London are divided into the sheep-like ‘proles’ and members of the Party who are kept under unremitting surveillance

1950 I, Robot by Isaac Asimov – nine short stories about ‘positronic’ robots, which chart their rise from dumb playmates to controllers of humanity’s destiny

1950 The Martian Chronicles – 13 short stories with 13 linking passages loosely describing mankind’s colonisation of Mars, featuring strange, dreamlike encounters with Martians

1951 Foundation by Isaac Asimov – the first five stories telling the rise of the Foundation created by psychohistorian Hari Seldon to preserve civilisation during the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1951 The Illustrated Man – eighteen short stories which use the future, Mars and Venus as settings for what are essentially earth-bound tales of fantasy and horror

1952 Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov – two long stories which continue the future history of the Foundation set up by psychohistorian Hari Seldon as it faces attack by an Imperial general, and then the menace of the mysterious mutant known only as ‘the Mule’

1953 Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov – concluding part of the ‘trilogy’ describing the attempt to preserve civilisation after the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1953 Earthman, Come Home by James Blish – the adventures of New York City, a self-contained space city which wanders the galaxy 2,000 years hence powered by spindizzy technology

1953 Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury – a masterpiece, a terrifying anticipation of a future when books are banned and professional firemen are paid to track down stashes of forbidden books and burn them

1953 Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke a thrilling narrative involving the ‘Overlords’ who arrive from space to supervise mankind’s transition to the next stage in its evolution

1954 The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov – set 3,000 years in the future when humans have separated into ‘Spacers’ who have colonised 50 other planets, and the overpopulated earth whose inhabitants live in enclosed cities or ‘caves of steel’, and introducing detective Elijah Baley to solve a murder mystery

1956 The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov – 3,000 years in the future detective Elijah Baley returns, with his robot sidekick, R. Daneel Olivaw, to solve a murder mystery on the remote planet of Solaria

1956 They Shall Have Stars by James Blish – explains the invention – in the near future – of the anti-death drugs and the spindizzy technology which allow the human race to colonise the galaxy

1959 The Triumph of Time by James Blish – concluding story of Blish’s Okie tetralogy in which Amalfi and his friends are present at the end of the universe

1961 A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke a pleasure tourbus on the moon is sucked down into a sink of moondust, sparking a race against time to rescue the trapped crew and passengers

1962 A Life For The Stars by James Blish – third in the Okie series about cities which can fly through space, focusing on the coming of age of kidnapped earther, young Crispin DeFord, aboard New York

1962 The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick In an alternative future America lost the Second World War and has been partitioned between Japan and Nazi Germany. The narrative follows a motley crew of characters including a dealer in antique Americana, a German spy who warns a Japanese official about a looming surprise German attack, and a woman determined to track down the reclusive author of a hit book which describes an alternative future in which America won the Second World War

1968 2001: A Space Odyssey a panoramic narrative which starts with aliens stimulating evolution among the first ape-men and ends with a spaceman being transformed into galactic consciousness

1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick In 1992 androids are almost indistinguishable from humans except by trained bounty hunters like Rick Deckard who is paid to track down and ‘retire’ escaped andys

1969 Ubik by Philip K. Dick In 1992 the world is threatened by mutants with psionic powers who are combated by ‘inertials’. The novel focuses on the weird alternative world experienced by a group of inertials after a catastrophe on the moon

1971 Mutant 59: The Plastic Eater by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis – a genetically engineered bacterium starts eating the world’s plastic

1973 Rendezvous With Rama by Arthur C. Clarke – in 2031 a 50-kilometre long object of alien origin enters the solar system, so the crew of the spaceship Endeavour are sent to explore it

1974 Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick – America after the Second World War has become an authoritarian state. The story concerns popular TV host Jason Taverner who is plunged into an alternative version of this world in which he is no longer a rich entertainer but down on the streets among the ‘ordinaries’ and on the run from the police. Why? And how can he get back to his storyline?

1974 The Forever War by Joe Haldeman The story of William Mandella who is recruited into special forces fighting the Taurans, a hostile species who attack Earth outposts, successive tours of duty requiring interstellar journeys during which centuries pass on Earth, so that each of his return visits to the home planet show us society’s massive transformations over the course of the thousand years the war lasts.

1981 The Golden Age of Science Fiction edited by Kingsley Amis – 17 classic sci-fi stories from what Amis considers the Golden Era of the genre, namely the 1950s

1982 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke – Heywood Floyd joins a Russian spaceship on a two-year journey to Jupiter to a) reclaim the abandoned Discovery and b) investigate the monolith on Japetus

1987 2061: Odyssey Three by Arthur C. Clarke* – Spaceship Galaxy is hijacked and forced to land on Europa, moon of the former Jupiter, in a ‘thriller’ notable for Clarke’s descriptions of the bizarre landscapes of Halley’s Comet and Europa