This is an outstandingly thorough, factual and authoritative account of the British Army’s involvement in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, maybe the most comprehensive, detailed and balanced account available.

Jack Fairweather

Jack Fairweather covered the Iraq War as the Daily Telegraph‘s Baghdad and Gulf correspondent for five years. He and his team won a British Press Award for their coverage. He went on to be the Washington Post‘s Islamic World correspondent. By the time this book was published he had become a fellow at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies.

It’s a solid work of 430 pages, consisting of 32 chapters with good maps, thorough notes, a list of key players, a useful bibliography, index and so on. Well done to the publishers, Vintage, for such a professional package.

However, something (obviously) beyond their control is that, having been published in 2012 means the narrative does not include the rise of ISIS and the chaos that ensued. Fairweather’s narrative is now over ten years out of date, a factor I’m coming to realise is vitally important when reading about this disastrous part of the world (Iraq-Iran-Afghanistan-Pakistan) and, in particular, putting the entire conflict in Afghanistan into context, given the swift collapse of the Afghan government and return to power of the Taliban in 2021.

Companion piece to Thomas Ricks’s Fiasco

Having read Fiasco, Thomas E. Ricks’s highly detailed accounts of the US decision making and planning leading up to the war, it’s fascinating to follow the same storyline from the British government point of view. For example, how the UK government made the same mistake of failing to consider or plan for the aftermath of the war, but for different reasons.

Tony Blair was the first British premier to be fully aware of modern media and how to use them. He and Alistair Campbell were all about focus groups, opinion polling and managing the news cycle and this is all short term thinking. Fixated as he and his team were on the media, they were obsessed that concrete proof the UK was planning for war shouldn’t leak out. Therefore Blair forbade the Department for International Development from officially commissioning post-invasion planning (the kind of thing it specialises in) in case someone leaked it (p.13). Similarly, Blair forbade the Army from placing orders for the kind of kit it would need for a large-scale deployment abroad (p.14). So Blair’s obsession with media management prevented him from properly, fully considering the post-conquest management of Iraq, from commissioning adequate plans for reconstruction, and from planning for the post-invasion policing by the British Army. Inexcusable.

Key points

Fairweather covers every detail, every aspect of the story, in calm, measured, authoritative chronological order. This really feels like the account to read.

1997 Tony Blair elected Prime Minister.

1998 Blair supports the Operation Desert Fox bombing campaign against Saddam. New Labour make the first increase to the military budget after a decade of Tory cuts.

March 1999 Blair succeeds in pushing the US and NATO to intervene in Kosovo with a bombing campaign against Serbia (with mixed results; see Michael Ignatieff’s book on the subject).

April 1999 Blair makes his Chicago speech making the case for intervention/invasion of countries on a humanitarian basis if dictators are massacring their people.

The 9/11 attacks change everything. President George W. Bush immediately starts planning an attack on Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. In October 2001 US forces began their attack, supporting the Northern Alliance against the Taliban government. The Taliban overthrown by December 2001. George Bush phones Tony Blair to sound him out about attacking Saddam Hussein.

The long tortuous process whereby the US tries to bamboozle the UN Security Council into agreeing a resolution allowing the invasion, and the New Labour government began its campaign of lies and deception, resulting in the dodgy dossier of fake intelligence, cobbled-together scraps from a PhD thesis including the ludicrous claim that Saddam could launch ‘weapons of mass destruction’ in 45 minutes. It was indicative of the way New Labour were obsessed by media and presentation and paid little attention to substance.

20 March 2003 The ‘coalition’ invasion of Iraq began. During the build-up, a variety of figures in the military and civil service discovered there was no plan for what to do after the invasion. It was mainly the Americans’ fault, Bush only set up an Office for Post-War Iraq a few weeks before the invasion and ignored advice contained in documents like Tom Warrick’s ‘the Future of Iraq’ project (p.15). Reconstruction was handed to retired general Jay Garner who rang round his pals to ask if any of them knew how to rebuild a country. Planning was ‘shambolic’ (p.21).

In London, Attorney General Peter Goldsmith had to be cajoled into reluctantly agreeing that invasion was legal without a second, specific UN resolution stating as much. How much he must regret that now (p.19). Alastair Campbell bullied ministers into kowtowing to Blair’s determination to march alongside the Americans i.e. be Bush’s poodle (p.19). Claire Short, Secretary at the Department for International Development, let herself be persuaded not to quit, something she regretted ever after.

Haider Samad and Iraqi stories

It’s worth highlighting that unlike most other books I’ve read on the shambles, Fairweather goes out of his way to include the stories of actual Iraqis. The first we meet is a man named Haider Samad. We hear about his family background, his wish to marry, intertwined with the history of Shiite religion in the southern part of Iraq. Samad will volunteer to become an interpreter for the British Army with ruinous consequences for himself and his family and Fairweather will return to his story at various points during the narrative as a kind of indicator of the British occupation’s broken promises and failures.

Names

Another distinctive feature of the book is the extraordinary number of named individuals Fairweather introduces us to, on every page, and their extraordinary range. Chapter 3 opens with Major Chris Parker patrolling Basra six weeks after the successful invasion has overthrown Saddam, to his commanding officer, Brigadier Graham Binns, a Scots Dragoon Officer Captain James Fenmore, Lieutenant Colonel Nick Ashmore, paymaster Ian Jaggard-Hawkins, Lieutenant Colonel Gil Baldwin of the Queen’s Royal Dragoons, the army’s top lawyer in Iraq Lieutenant Colonel Nicholas Mercer, SAS commander Baghdad Richard Williams and hundreds and hundreds more.

On one level the book is a blizzard of individual names and stories of soldiers engaged in this or that aspect of the occupation, which is what makes his nine-page list of Dramatis personae at the end of the book invaluable.

Back to the narrative

Defence Minister Geoff Hoon made as light of the epidemic of looting which broke out in the aftermath of the invasion as Donald Rumsfeld did, claiming the looters were ‘redistributing wealth’, which was a good idea. Idiot (p.29).

The thing is, the British had invaded Basra before, back during the Great War when we were seeking to defeat the Ottoman Empire which had allied with Germany and Austria. Hence the Commonwealth War Cemetery which Sniper One Dan Mills discovered in al-Amarah and gave him a fully justified sense of ‘What are we doing back here a hundred years later’? Now, as then, after overthrowing the ruling elite, the British discovered there weren’t many capable native Iraqis to run anything, even to form a town council. Eventually, they picked on a Sunni tribal leader to run a majority Shia town, Basra, an error of judgement which, of course, immediately triggered widespread protests (p.31). Ignorance.

Fairweather details how, struggling with the number of detainees and ‘suspected terrorists’ they were being sent, British military police and soldiers came to abuse and intimidate the rapidly increasing number of ‘terrorist’ detainees, set up kangaroo courts and deliver summary justice (p.33). This led to the scandal surrounding Corporal Daniel Kenyon and colleagues who took photos of themselves abusing Iraqi prisoners at ‘Camp Breadbasket’, which leaked out, led to their arrests and trial and conviction (pages 46 to 48). The British version of the Abu Ghraib scandal. All the politicians’ claims about moral superiority of the West went up in smoke.

After less than 2 months flailing to run an office of reconstruction, Jay Garner was fired and replaced by L. Paul Bremer who was the ‘right kind’ of Republican i.e. a devout Christian and neo-conservative (p.40). He was put in charge of the newly created Coalition Provisional Authority. He was to prove a relentless, impatient workaholic who took catastrophic decisions and plunged Iraq into a civil war and vicious ethnic cleansing.

Fairweather chronicles the key role played by Douglas Feith (under secretary of Defense for Policy from July 2001 until August 2005) in persuading Bremer to completely disband the Iraqi army and remove everyone with high or mid-level membership of Saddam’s ruling Ba’ath Party from their jobs. At a stroke this threw half a million well-trained young men (the army) onto the dole queue and a hundred thousand people with managerial experience (Ba’ath) ditto. Bremer refused to listen to the argument that most Ba’ath Party members cared nothing about the party’s ideology, that being a member was simply a requirement of holding senior posts like hospital consultant or head of the power or water systems. Bremer didn’t listen. They were all fired. Chaos ensued.

From these angry men whose lives were ruined by L. Paul Bremer sprang the insurgency. Tim Cross, a British logistics expert who worked with Garner till he quit in disgust called American efforts ‘chaotic’ and a ‘shambles’ (p.41).

Britain contributed 40,000 troops to the initial invasion. By mid-summer 2003 half had returned to Blighty. General Sir Mike Jackson became head of the British Army.

September 2003 the BBC Today programme quoted an anonymous source claiming that New Labour officials ‘sexed up’ the ‘dodgy dossier’ which we went to war on, infuriating Alastair Campbell. The label was to stick to this day (p.50).

A section about the history of the Marsh Arabs, going back to the first occupation of Iraq by the British during and after the Great War. The exploits of Gertrude Bell, who crops up repeatedly in Emma Sky’s account of her time in Iraq (p.52). The Marsh Arabs’ history of independence and revolt against central authority. The disastrous way they were encouraged to rise up against Saddam by President George Bush who then failed to provide any support so that tens of thousands were slaughtered by Saddam’s forces. Then Saddam’s decade long project to drain the marshes altogether and destroy their way of life, which he had just about achieved by the time of the 2003 invasion.

Maysan was the only Iraqi province to liberate itself from Saddam’s security forces and had no intention of kowtowing to the foreign invaders. Into Maysan province, came the Third Battalion the Parachute Regiment, famous for their gung-ho approach. Fairweather quotes Patrick Bishop’s description of the paras from his book ‘3 Para’ (2007) which I’ve reviewed.

Angry protests against the occupying forces started straight away, with stones being thrown, and then the first shots being fired. It was Northern Ireland all over again, but without the half a dozen crucial elements which made Northern Ireland, in the end, manageable (itemised in Frank Ledwidge’s outstanding book on the subject). In Basra, unlike Ulster, there was a lack of clear government authority, and the lack of a reliable police force to work alongside, the lack of a shared culture and language, and the lack of enough men to do the job.

In a series of incidents which he described in great detail (‘From the rooftop Robinson shouted, “Remember lads, you’re fucking paratroopers”‘), Fairweather traces the quick degeneration of the ‘peacekeeping’ mission into a fight for survival against hostile crowds and growing numbers of highly motivated, highly armed local ‘insurgents’.

The soldiers of 1 Para were only faintly familiar with the region’s history and how it had bred a culture of suspicion of outsiders. (p.55)

Fairweather gives a detailed forensic account of the killing of six military police by an enraged crowd after they got trapped in the police station of Majar al-Kabir on 24 June (pages 55 to 63). Critics focused on the lack of equipment, specifically a satellite phone to call for help, and their insufficient ammunition. Having read Lewidge’s book, though, I understand how the soldiers had been put into a completely untenable position by the naive over-optimism of the politicians (Blair) and the failure of the army general staff either to stand up to the politicians (to say no) and then to provide adequate intelligence, adequate equipment but, above all, a clear strategy to deal with the worsening situation.

Fairweather describes the arrival of a new British civil servant, Miles Pennett, sent to work with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Baghdad and the chaos he found there created by teeming hordes of graduates all fresh out of American universities and selected solely for their adherence to right-wing neo-conservative Republican values (p.69).

(In his book ‘Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Baghdad’s Green Zone’ , American journalist Rajiv Chandrasekaran tells us candidates for the CPA were interviewed about their views on abortion or neo-liberal economics rather than any technical qualifications or experience whatsoever. This explains the CPA’s reputation for chaos and incompetence.)

While things fell apart in Iraq, Tony Blair flew to the States to receive a Congressional Gold Medal and make a grandstanding speech to the Congress. It shifted a complete change in the aims of the occupation. Gone was mention of the weapons of mass destruction which had so feverishly justified the invasion. Now, it turned out, the occupation was about bringing universal values of democracy, human rights and liberty to ‘the darkest corners of the earth’ (p.70).

In other words a) indistinguishable from Victorian rhetoric about civilising India or Africa which justified control and occupation; and b) bullshit, because i) quite a few ‘places’ don’t particularly want ‘democracy, human rights and liberty’, they want food and water so they don’t starve to death and, next above that, security: maintenance of law and order so it’s safe to walk the streets. That – basic security – comes a million miles before Western values and, in the event, the occupying forces in both Iraq and Afghanistan turned out to be unable to provide them.

And ii) because as explained at the start of this review, Western-style democracy was never an option for Iraq, with its complex and corrupt matrix of tribal, ethnic and religious allegiances; and never, ever a possibility in Afghanistan.

Pride comes before a fall. The day after Balir received his congressional medal the body of David Kelly, the weapons expert, was found in a wood. He had committed suicide. He had been the source for BBC journalist Andrew Gilligan’s story about the ‘sexed up’ dossier about WMDs the government used to deceive MPs into voting for the war. Hoon and Campbell had pressed for Kelly’s name to be leaked to the press in order to discredit him. It never actually was leaked but enough information was provided for the press to be able to identify him. Snared in a political mesh he could see no way out of without ruining his reputation, Kelly took his own life. Alastair Campbell was forced to resign. The New Labour government was snared in scandal (pages 70 to 73).

All this distracted from the worsening situation in Baghdad. Fairweather’s account is super-detailed. He gives precise names, careers, quotes for hundreds of the personnel deployed to the CPA in Baghdad and to run Basra Province. It was the usual cobbled-together, last minute list of candidates as had characterised the hurried creation of Jay Garner’s short-lived Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance: a former director at a merchant bank was appointed finance minister, a public schoolmaster was appointed minister of education, an internet entrepreneur was made minister for trade and industry (p.67).

The advent of Sir Jeremy Greenstock, UK ambassador to the UN, now despatched to the court of Paul Bremer at the Coalition Provisional Authority and the difficulties he encountered, namely the Americans steamed ahead doing whatever they wanted to (dissolved the 500,000 strong Iraqi army, sacked 100,000 Ba’ath Party members from their jobs, delayed elections) and ignored him.

The Anglo-American relationship that Blair had gone to war to strengthen was coming under serious pressure. In fact it was increasingly difficult to find areas where British and American views matched. (p.79)

America’s disastrous early efforts to ‘train’ a new Iraqi police force, handed to Bernie Kerik, a former New York City police commissioner (p.79). Rumsfeld tries to reduce the budget required to train a new army. Fairweather strikingly calls Rumsfeld ‘a bully’ (p.80).

Typical neo con plans to privatise Iraq’s hundreds of state-own industries in one fell swoop, to be masterminded by former venture capitalist at Citicorp, Tom Foley (p.80). Chandrasekaran is very funny about the complete lunacy of this ideas and its ruinous impact on an economy already on its knees.

As a presidential election year approaches, the politicking in the US, Bush reshuffles his team.

Rumsfeld, whose grasp on the chaos he had created was tenuous, was removed (p.83)

Condoleeza Rice takes over. Arguments about the new Iraqi constitution, when it should be drawn up, who it should be drawn up by, whether or not it could form the legal basis for elections, when those elections should be held, what kind of form they take (Bremer preferred US-style electoral colleges rather than a simple poll).

By the end of 2003 Iraq fatigue had set in in London. Blair’s entire personality was built around can-do optimism and so found it difficult to cope with the relentless bad news from Iraq. And he’d lost Campbell, his key advisor and media manipulator.

By October 2003 the British administration in Basra accepted the fact that it was, in effect, an imperial occupation, and moved into Saddam’s palace. Fairweather shows us how it worked through the eyes of Sir Hilary Synnott, Regional Coordinator of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Southern Iraq from 2003 to 2004.

The problem of the UK Department for International development, populated by progressives who strongly opposed the war, and the occupation, were desperate to escape accusations of imperialism, but were entirely dependent on the military pacifying the place before they could do a stroke of ‘development’ work.

When development minister Hilary Benn and permanent undersecretary Suma Chakrabarti flew into Basra it was to discover the army commander, Major General Graeme Lamb, mired in controversy because some squaddies from the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment had just arrested seven Iraqis, took them back to base, hooded them, abused and beat and tortured them, till one of them, Baha Mousa, died (p.86). What was it Tony Blair was saying about bringing universal values of democracy, human rights and liberty to ‘the darkest corners of the earth’?

Meanwhile the other provinces of southern Iraq needed governing. Fairweather introduces us to the men selected for the job, being: Mark Etherington, former paratrooper; old Etonian Rory Stewart, whose account of his time in the role I’ve reviewed; old Etonian John Bourne; Emma Sky, former British Council worker, whose account I’ve also reviewed (p.89).

Fairweather makes the simple but penetrating point that a certain type of posh Englishman has always ‘loved’ and identified with the Arab way of life because it echoes the primitive hierarchy and independence (for tribal leaders) which used to exist in Britain, in medieval to early modern times. They instinctively identified with the feudal setup which reminded them of their own country estates and venerable lineages.

Anyway, these Brits were handed entire provinces to run, exactly as in the high days of empire when jolly good chaps ruled provinces the size of France or more. Their efforts were so amateurish it’s funny. Adrian Weale was handed the task of organising elections in Nasariyah. He had no idea how to do this so emailed his wife, a borough councillor in Kensington and Chelsea (of course), and asked her to send him guidelines for local elections in Britain, to be adapted for Iraq. Making it up as they went along.

None of this stopped Stewart, in Maysan, having problems with the self-styled ‘Prince of the Marshes’, Abu Hatem, while Etherington, 100 miles north, appointed governor of Wasit, whose northern border touched Baghdad, was beginning to have trouble from the followers of Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr and his devoted followers. In a telling sentence, Fairweather says: ‘Sadr was organising faster than the British’ (p.91). Sadr established his own parallel provisional government for Iraq and declared any government created by the British or Americans illegitimate (p.91).

In November Etherington attended a conference of US business donors in Baghdad and was astonished at how out of touch the CPA was. Even the US military was surprised at being kept out of the loop by Bremer and his secretive cabal of advisers.

Back in Amara Stewart was involved in a complicated sequence of events which led to rioters looting the office of the local governor, who had been inserted into the job by the egregious Abu Hatem. British troops found it hard to contain brick-throwing mobs. Stewart reflected that his Victorian forebears believed in their mission and were committed to the long-term development of their countries. Deep down Stewart knew that wasn’t true of Britain.

2004 uprisings

All the allies had growing misgivings about the growing power of Muqtada al-Sadr. In March 2004 Bremer took the publication of a series of articles lambasting the Coalition Provisional Authority in Sadr’s newspaper, Al-Hawzat as a pretext to shut it down. On 3 April US troops arrested the editor, sparking protests. On 4 April fighting broke out in Najaf, Sadr City and Basra. Sadr’s Mahdi Army took over several points and attacked coalition soldiers, killing dozens of foreign soldiers. This was the start of the Sadr Uprising in the south of Iraq.

What made the situation ten times worse was that on 31 March gunmen ambushed four American contractors outside Falluja to the west of Baghdad, beat them to death, burned their bodies and hung them from a bridge over the river Euphrates. Footage was beamed round the world. Bush was horrified and vowed revenge.

Suddenly the occupying forces were faced with a Sunni uprising in the so-called Sunni Triangle to the West of Baghdad, and a parallel but separate uprising by violent forces loyal to Sadr in every town in the south.

Fairweather details the experience of Mark Etherington in the Cimic compound at Kut as fierce fighting breaks out between the Shia militia and the Ukrainian UN troops. Here and in all the other towns of south Iraq, the UN and CPA compounds came under intense fire. The Americans’ actions against Sadr in Baghdad effectively plunged southern Iraq into war. Etherington knew all about the catastrophic defeat of a sizeable British Army at Kut by Ottoman troops during the First World War one hundred years earlier (p.109). Fairweather gives a brilliantly vivid and nail-biting description of Etherington and his staff abandoning the compound at Kut. The same kind of thing was happening at Nasariyah under its Italian governor, Barbara Contini.

Meanwhile, the President had ordered the US army to enter the town of Fallujah and find the people responsible for the murder of the civilian contracts. This ridiculously impossible task of course led to all out war and the First Battle of Fallujah. All round the world were beamed footage of houses being destroyed, terrified civilians being rounded up, and thousands of refugees fleeing the city as the civilian casualties grew into the hundreds. All round the Arab world young men decided they had to go to Iraq to fight these genocidal invaders.

Fairweather quotes part of a George Bush speech which epitomises one of the American’s conceptual stupidities, where Bush says: ‘the American people want to know that we’re going after the bad guys’ (p.111). These simple-minded dichotomies, the binary polarities of a thousand Hollywood movies, which divide people up into the Good Guys (John Wayne, Bruce Willis) and the Bad Guys (wearing black hats), governed US policy throughout the twentieth century. This worked fine when there really were Bad Guys, like the Nazis, but not so well in societies riven with complex ethnic, religious, social and political divides, such as Vietnam or Iraq where there’s a wide variety of bad actors and it becomes impossible to figure out who the ‘good’ ones are, if any.

Obviously, in order to bring the ‘murderers to justice’ many times more US troops were killed and injured than the original 4 contractors. In the end 37 American soldiers were killed and over 600 Iraqi civilians. Huge parts of a major city were devastated. Inevitably, the supposed murderers of the contractors were never found.

Apart from the obvious security issues, it caused a political issue because the entire Sunni membership of the provisional Iraqi government which Bremer was trying to cobble together threatened to quit, and could only be made to support coalition forces with an extreme of arm-twisting and promises of money and influence.

Meanwhile, in the south of Iraq, US forces retook the CPA compounds in Kut, Amarah and Nasariyah, but the British consuls who returned to their posts had abandoned all thoughts of reconstruction and development. Not getting killed became their number one priority (p.113).

Bremer was strongly critical of the British failure to secure the south, exacerbated by negative coverage of the American butchery in Fallujah in the British press, plunging American-British relations to a new low and this led to a significant outcome. Bremer banned British representatives from the ongoing discussions with local politicians about the forthcoming constitution and elections.

Britain’s effective involvement in shaping Iraq’s political future was over. (p.114)

In late April the photos of American abuse of Iraqi prisoners at the notorious prison at Abu Ghraib to the west of Baghdad emerged. I’ve described it elsewhere. Bringing ‘universal values of democracy, human rights and liberty’ eh?

For a spell Fairweather’s text overlaps the narrative of Sergeant Dan Mills, sniper with the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, in his bestselling book, Sniper One. Mills describes how, on the very first patrol on the very first morning of the very first day of their deployment, Danny and his patrol parked up outside the local headquarters of Sadr’s Mahdi Army or Jaish al-Mahdi as it was properly called, JAM as the Brits called it. Mills’s patrol did this in complete and utter ignorance of the local geography, town layout, and local sense of bitter resentment of the infidel occupiers.

The JAM attacked, using machine guns, rocket propelled grenades and mortars, and Danny and his mates found themselves in the middle of a series of intense firefights and attacks which continued on a daily basis until their eventual withdrawal from the Amarah government compound four months later.

The Americans had now surrounded al-Sadr who was holed up in the Imam Ali Shrine in the holy city of Najaf where their attempts to break in had damaged some parts of the shrine. Shia anger was off the scale. Danny and his mates and all UK forces across the south of the country had to deal with the consequences. Fairweather gives a series of absolutely gripping, vivid, terrifying eye witness accounts of the running battles and firefights which followed.

The Prince of the Marshes, Abu Hatem, threw in his lot with the Sadrists. When the Brits made a raid to capture insurgents and took prisoners back to their prison, the detainees were subject to abuse and heard screams and torture sounds from other cells. When eventually released these stories helped recruit more insurgents and incentivise existing ones into a life or death struggle against the invader. Public relations catastrophe (p.123).

Escape to Afghanistan

In January 2004 the Hutton Inquiry into David Kelly’s death acquitted the government of blame and BBC Director General Greg Dyke resigned, but much of the media accused the report of being a whitewash. Fairweather quotes cabinet colleagues who noticed the impact the strain was having on Blair’s face. Hs hair started to turn grey.

In June 2004 a NATO conference decided the US-led mission had languished because of the focus on Iraq and volunteered NATO forces to take a more active role in Afghanistan. Why? Use it or lose it. NATO had big budgets from member countries who periodically wondered why they were spending so much. This would give the organisation the sense of purpose it needed.

In London Blair and his team saw it as an opportunity to regain the initiative. In Iraq we were not only visibly losing but being sidelined in every way imaginable by the Yanks. Deployment to Afghanistan offered the British Army a chance to redeem its damaged reputation and Tony Blair a way of restoring his reputation as an international statesman.

In fact the Americans had specifically asked the Brits to relocate NATO’s Allied Rapid Reaction Corps to the south of Iraq. It was crunch time. Fairweather describes the nitty gritty of discussions, with pros and cons on both sides. But the Brits decided to cut and run. Iraq was a swamp where the Americans disrespected us. Afghanistan offered a second chance. But could we fight a war on two fronts? The decisive view was given by director of operations at the Ministry of Defence, Lieutenant General Robert Fry. He argued that troop deployments to Afghanistan would be ramped up as troops in Iraq were drawn down. This was ratified by Chief of the Defence Staff Michael Walker. They’re the men to blame.

Fairweather gives a detailed analysis of the politics around successive Defence Reviews, with the Treasury constantly trying to cut the military budget and the top brass looking for any arguments to increase it. This in turn was meshed with the bitter rivalry between Blair the international grandstander and Gordon Brown, morosely hunkered down as Chancellor of the Exchequer. So another reason for the Afghan Adventure was entirely due to Whitehall politicis, in that the deployment forced a reluctant Treasury to release more money to the Ministry of Defence.

Chapter 13

Cut to a fascinating chapter about dismal attempts to train a new Iraqi police force, told through the eyes of Brit trainer William Kearney, 12 years in the Special Branch and now manager of ArmorGroup security, one of the many contractors who worked in Iraq. Compare and contrast with the American approach which was to flood the streets with poorly trained ‘police’ provided with uniforms, guns and ammunition which they quite regularly sold onto the insurgents.

We meet up again with Iraqi Haider Samad who is working for the Brits in Basra as an interpreter and the time he was beaten to the ground by four strangers who tell him next time they’ll kill him if he carries on working for the infidel. Haider’s experience is a peg to introduce the wider issue that many, many of the new ‘police’ being recruited at such speed in order to make Western politicians happy, were themselves members of the Shia militias.

Chapter 14

Introduction to the leader of Jaish al-Mahdi in Basra, Ahmed al-Fartosi, and his aim to utterly destroy the British occupation. He was convinced the Brits wanted to extend their occupation forever because their real aim was to steal Iraq’s oil. He had spent some time in exile in Lebanon and so on return to Basra reorganised the militia along the lines of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah. That said, Fartosi was no fan of the Iranians who had fought Iraqis in a bitter eight-year-long war. Half a million Iraqis died in that war and Iran came close to capturing Basra.

Another one of Fairweather’s gripping descriptions of a firefight which broke out on 9 August in Basra between British forces and the Shia militia led by Fartosi who ambushed a patrol forcing them to take refuge in nearby houses and call for backup etc.

Amara Fairweather cuts to the similar situation in Amara where sniper Mills and his buddies were included in the 150 or so coalition troops defending the Cimic House compound from daily attacks and hourly mortar bombs. After a particular intense firefight all the Iraqi cooks and ancillary staff leave, taking as much loot with them as they could carry. Fairweather then gives his version of the siege of Cimic House, the intense battle which forms the centrepiece of Mill’s book, Sniper One (pages 155 to 158).

Soon afterwards al-Sadr caved to majority Shia opinion and called off his insurgency. The far more influential cleric Grand Ayatollah Sistani had returned to the country, gone to Najaf and seen the damage to the shrine which he, and moderate Shia opinion, blamed on Sadr. Hence his climbdown.

Fairweather switches from his intense description of combat right up to the highest level of politics and the scheming by Iraqi exile Ayad Allawi to curry favour with the Americans and get himself appointed new president of Iraq. All the accounts I’ve read describe Allawi as a plausible swindler who promised Bush and Rumsfeld whatever they wanted to hear, thus materially aiding the misconceptions and lack of planning on which the invasion was launched.

Fairweather drolly explains that this plausible chancer was put on the payroll of MI6 and ‘supplied the British government with some of the most flagrantly misleading intelligence before the war, namely the completely bogus claim that Saddam could launch weapons of mass destruction in 45 minutes (p.131). This crook had Bush and Blair’s enthusiastic personal support.

In November the Americans launched the Second Battle of Fallujah with a view to exterminating Sunni insurgents and establishing the rule of law. The battle saw some of the heaviest urban combat the American army had been involved in since the ill-fated Battle of Hue City in Vietnam in 1968. 95 American and 4 British soldiers were killed, along with up to 2,000 ‘insurgents’. Over a fifth of the city was destroyed.

2005 election A general election for the interim Iraqi parliament was held on 30 January 2005. Sunni Muslims, despite being a minority in Iraq (64% Shia, 34% Sunni, 2% Christian and other) had historically held power. Saddam and his clique were Sunnis. Now, in protest against the battle of Fallujah and the perceived bias of the occupying force towards Shias, large numbers of Sunnis boycotted the elections. This was self-defeating as it gave sweeping victory to Shia parties backed by Grand Ayatollah Sistani. Allawi’s parties polled just 14%.

Both Americans and Brits now had to deal with an ‘elected’ Iraqi government dominated by Shias who, far from being grateful to their liberators, were deeply suspicious and resentful of them.

Chapter 16

Fairweather switches focus to a new location, the south of Afghanistan, giving us a potted history of Britain’s ill-fated military adventures here during the nineteenth century, notably the swingeing defeat at the Battle of Maiwand, 27 July 1880, heaviest defeat of a Western power by an Asian power until the prolonged Ottoman siege and massacre of the British at Kut in southern Iraq in the winter of 1915/16

Cut to 2004 as the British Army staff begin to plan a deployment to Afghanistan. Now that elections had taken place, British planners and politicians looked for a way to extract the army from Iraq. The task fell to Major general Jonathon Riley who adopted the formula of the Americans: as the Iraqi police force ‘stepped up’, the British forces would ‘step down’. Sounded good but conveniently ignored the fact that the so-called ‘police’ were very poor quality, corrupt if you were lucky, at worst – during many of the clashes of the Sadr Uprising – joining the insurgents in shooting at British troops. When the police were objective and reasonably independent, they were themselves liable to attack. In the first half of 2005 350 police officers were killed in attacks on police stations and recruiting centres.

We remeet the Brits handed the challenging job of training Iraqi police, namely William Kearney and Charlie MacCartney, police mentor of the Jamiat; SIS station chief Kevin Landers. Fairweather details the process whereby all these guys come to realise that the head of the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU) Captain Jaffar, was deeply in league with the insurgents. In fact the SCU was to become a growing bugbear in the Brits’ side, and establish itself as a centre of criminality and extortion against the civilian population.

Elections are all very well but the January 2005 ones put Sadr party members into Basra’s provincial council and into the governor’s seat. But the Brits didn’t want to stir up a hornet’s nest. They were now planning to withdraw all but 1,000 British troops from Iraq by end of 2005, with a view to redeploying them to Afghanistan at the start of 2006.

How did the Brits get deployed to Helmand, right next to the historic battlefield of Maiwand, home of the fiercest, most invader-resistant traditions in all Afghanistan? Well, remember the whole thing was a NATO operation. The Canadians had lobbied hard to have overall control of the deployment to south Afghanistan and called first dibs on the biggest town, Kandahar. Considering the alternatives, the Brits learned that Helmand Province had now become the biggest single source of heroin, which would please the army’s civilian master, Tony Blair. And it was also the historical homeland of the Taliban, so combatting them would also give political brownie points to Blair, keen to rehabilitate his ailing reputation.

Chapter 17

At this point Fairweather cuts away to catch up on the career of interpreter Haider who was now working for a private security firm. His boss was William Kearney who we’ve seen trying to train the Iraqi police. Haider has saved up enough money to propose to his childhood sweetheart, Nora, whose family previously banned the match due to his lack of money.

Chapter 18

Reg Keys’s son, Tom, was one of the six military policemen murdered by the mob at Majar al-Kabir police station in June 2003. Fairweather devotes some time to chronicling Keys’s campaign to get to the bottom of his son’s death but his increasing frustration with MoD prevarication. The army board of enquiry published its findings nine months later. The families of the dead were not invited to contribute or to attend. They asked for advance copies on the eve of publication but were refused. They were given just an hour to read the 90-page report ahead of a meeting with Defence Secretary Geoff Hoons. Despicable.

Arguably the limited and obviously parti pris ‘enquiries’ into the launching of the war, the David Kelly affair and the red caps’ deaths went a long way to discrediting the entire idea of a government enquiry.

The angered parents set up a support group, Military Families Against the War (p.253). But they went further and funded Keys to stand in Tony Blair’s constituency of Sedgemoor in the 2005 general election. Fairweather gives a characteristically thorough and fascinating description of how what started as a jokey suggestion over a coffee was turned into a serious political reality, giving us lots of information about the working of modern British political parties and the media.

Just before the election Channel 4 News leaked a March 2003 memo from Attorney General Peter Goldsmith giving his opinion that he didn’t think the case for war would stand up in a court of law. Only days later a soldier in Amarah was hit by a roadside bomb and killed. The war wouldn’t leave Tony Bair alone. You broke it; you own it.

In the general election Blair’s share of the vote went from 65 to 59% and Reg won 10%. Labour’s majority in the House of Commons was cut from 200 to 66 MPs. So not a defeat. In fact pollsters considered the Iraq war a minor issue. The economy was booming and lots of people didn’t care all that much (as, arguably, most sensible people don’t care about any form of politics).

(Page 197 quote from Ibn Saud, future king of Saudi Arabia, on the irredeemably rebellious nature of the Iraqi tribes who can only be governed by ‘strong measures and military force’.)

Chapter 19. Iran

Rocky relations between the Brits in Amarah tasked with patrolling the porous border with Iran, just 50k away, and the newly elected governor, Adel Muhoder al-Maliki. More descriptions of firefights and attacks the latest troop of British soldiers come under within minutes of leaving the heavily defended Amarah air base. The point is that the incredibly brave bomb disposal officer, Captain Simon Bratcher, not only neutralised a clutch of roadside bombs but provided the first evidence that they were being supplied by Iran.

The Shia government It’s all very well organising ‘free and fair elections’ until they end up voting in people you strongly disapprove of. Two months after the January 2005 elections, Ibrahim Jaafari, the leader of Dawa, one of the two main Shia parties, was announced as the next Iraqi Prime Minister. The Interior Ministry was handed to Bayan Jabr, a former commander of a Badr Brigade i.e. one of the main Shia militias. These men continued to further Iran’s influence at every level of the Iraqi administration. The Interior Ministry was said to have set up death squads to kidnap, torture and execute former Ba’ath Party members and Sunni leaders.

Jack Straw learns of an American plan to set up death squads to ‘take out’ leading Iranian agents working in Iraq militia leaders, but vetoes it (p.. (Did they go ahead anyway?) Straw’s objections were about not upsetting the Iranians at a difficult time of negotiations with the West about Iran’s nuclear power programme. But it’s one example among hundreds of how Iraqi politics became steadily more entangled with Iranian.

Fairweather makes an interesting point. Iranian policy in Iraq often seemed contradictory – at the same time supporting the Shia-led government but also backing anti-government militias. But why shouldn’t Iran be like Western countries, with conflicting parties and factions jostling for power and implementing different, sometimes conflicting strategies? Also: why not make it a conscious strategy to back different parties and factions while it was unclear who would win (p.204). In the end, of course, Iran won.

Chapter 20. Jamiat

This was the name of the police station in Basra which had become the focal point of corruption, extortion, kidnapping, torture and militia influence. Major Rupert Jones of the newly arrived 12 Mechanised Brigade decided to do something about it and asked for a list of possibly corrupt policemen. It became an uncomfortably long list. The Brits asked for them to be removed. Nothing happened. Then they asked for Fartosi to be arrested but learned that Fartosi had been put on a ‘no lift’ list because the prime Minister didn’t want to antagonise the Sadrists on whose support his government rested.

Kidnap of two SAS officers

Then three British soldiers were killed by roadside bombs and Brigadier John Lorimer, the eighth brigade commander in Basra in two years, decided to act. On 17 September an SAS detachment infiltrated Fartosi’s home and arrested him. Two days later two SAS officers on patrol were kidnapped. Fairweather describes in detail the complex standoff which then followed as several sets of British officials ascertained that the two soldiers had been taken to the notorious Jamiat police station. When British officials went to the station they were themselves promptly arrested and detained. Negotiations involved an Iraqi judge, and an increasing battery of coalition lawyers and officers. The negotiators were themselves hustled at gunpoint to the cells where the two soldiers were being kept, as fighting broke out at the front of the police station, with Iraqi police officers who the British had spent time and money training now opening fire on British forces. British relief forces were surrounded by angry crowds throwing bricks and a succession of Warrior vehicles were set on fire.

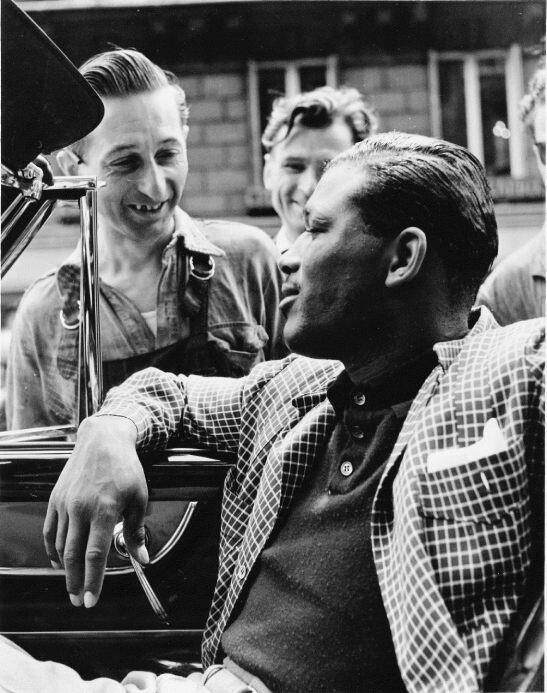

Sergeant Long escaping from his Warrior armoured vehicle after a petrol bomb was thrown down the gun turret (source: Reuters)

Eventually the SAS men and the other Brit hostages were rescued by an attack by SAS men who were brought all the way from the regiment’s HQ at Herefordshire to help them. The political fallout was threefold. 1) Pictures of George Long on fire escaping from his Warrior tank covered the front pages of British newspapers alongside articles claiming the British softly-softly police in Basra was a shambles. 2) More specifically, it revealed that the entire concept of training the Iraqi police force which politicians from Blair downwards had put such emphasis on, was in fact a sham. 3) The Shia governor, Muhammed al-Waeli, forced to take sides, came down on the side of his Shia constituency, accused the Brits of terrorism, led a tour of the now devastated police station, and declared he would never have anything to do with the Brits again.

Fairweather is outstanding at giving detailed forensic accounts of this kind of event (compare his description of the murder of the military police at Majar al-Kabir).

Chapter 21. Helmand

7/7 suicide bombers

On 7 July 2005 four British Muslims carrying backpacks full of explosives detonated them on London Underground trains and a bus. These were the first suicide bombs on British soil. They killed 52 and injured over 700. In a pre-recorded video one of the bombers described his motivation as revenge for all the innocent Muslims the British Army was killing in Iraq and Afghanistan. So much for our invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan making Britain safer. The exact opposite.

But when news came out that the men had been trained at terrorist training camps on the Pakistan-Afghan border, government spin doctors turned it into a justification for deploying British troops to Afghanistan.

In September 2005 Lieutenant General Rob Fry, the individual most responsible for the plan to deploy to Helmand, presented John Reid with the MoD’s plans to deploy 3,150 troops, mostly drawn from the Parachute Regiment. British forces would take over an American base named Camp Bastion in the desert north-west of the province’s capital, Lashkar Gah. He promised that Taliban fighters crossing from Pakistan would be easy to identify and eliminate. ‘The senior SIS men in the room rolled their eyes’ (p.225). Brigadier Ed Butler was chosen to command the force.

Fairweather shows the gulf between the top of the army (Fry and Chief of the General Staff Sir Mike Jackson) who assured sceptical politicians that it could be managed as long as the Brits withdrew their forces from southern Iraq at the same speed that they deployed them to Helmand – and many of the officers on the ground who thought it was madness. Defence Secretary John Reid was sceptical. ‘Won’t British troops be isolated and exposed?’ he asked (p.225). Fry assured him not. Reid was right. Fry was way wrong.

Split command

Right from the start it was ballsed up. The British formed part of a NATO force commanded by the Canadians. Because the Canadian force was being commanded by a brigadier, army etiquette demanded that Butler step aside to allow a more junior officer to command his men, and so Colonel Charlie Knaggs became commander of the British deployment. This meant Butler would have to oversee operations from Kabul. Then he discovered his headquarters would not be doing the operational planning but that a staff officer from army headquarters in Northwood would be drawing up the crucial operational plan.

Crucially, Butler would only have four Chinook helicopters at his disposal, barely enough to support one offensive mission a month and, it would prove, not nearly enough to extract British soldiers from the umpteen dangerous contact situations they were going to get into.

After the Jamiat police station siege, senior officers considered advising against the deployment, realising that the situation in south Iraq was far worse than previously understood, and would entail a much slower withdrawal than planned but they never made their opposition clear enough.

Sher Mohammed Akhundzada

Before the troops arrived the Brits made another mistake. UK ambassador to Kabul, Rosalind Marsden, persuaded president Hamid Karzai, to remove the province’s long-time governor, Sher Mohammed Akhundzada. He was notorious for rape, murder and involvement in the drugs trade, so getting rid of him played to press releases about Tony Blair’s counter narcotics policy. Unfortunately, Muhammed may have been a criminal but he was the only person with the contacts and authority to keep a lid on the province. Later, he cheerfully told British officers that, removed from his position of influence and no longer able to pay them, he let his 3,000-strong fighting force defect en masse to the Taliban. At a stroke the Brits made violent conflict inevitable and created a huge opposition force. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. That motto should be carved on Tony Blair’s tombstone.

Fairweather describes the efforts of the chief planner Gordon Messenger and development experts to assess the province, their dismay at the illiteracy and corruption of the Afghan administrators and police they met, and their equal dismay at the ignorance about Helmand displayed by British politicians and army staff. The politicians had assigned the army a three-year deployment. Development expert Minna Jarvenpaa said it would take ten years, probably longer, to begin to develop such a place (p.233). Politicians didn’t want to hear. No-one listened.

Details of the deployment were announced in January 2006, just in time for a conference of Afghan donors’ which Tony Blair was chairing. John Reid declared we were going to spend three years in the south of Afghanistan, bringing peace and security and helping the locals reconstruct their country. None of this was to happen.

Gil Baldwin, head of the Post Conflict Reconstruction Unit resigned in disgust, saying it beggared belief that Britain was preparing to go into Afghanistan even worse prepared then it had been for Iraq (p.234).

Chapter 22

Introduces us to the first soldiers to deploy to Afghanistan including Will Pike and Harvey Pynn of the Third Parachute regiment, 3 Para. This part of the narrative exactly matches the account of 3 Para’s time in Helmand (April to October 2006) given by Patrick Bishop in his rip-roaring soldier’s eye view of endless firefights in ‘3 Para’.

Fairweather repeats the surprising fact that, of the 3,500 British troops being deployed, all but 600 were support staff, engineers, cooks, drivers, quartermasters, ammunition handlers and so on. Governor Daoud wanted the Brits to deploy to protect towns in the north of the province from the Taliban. Butler was reluctant but agreed to support local Afghan army units. Development consultant Minna Jarvenpaa knew the tribal situation around Sangin was complicated with the town divided between two tribes, and both involved in rival drug operations.

In May 2006 Daoud sent the British commander, Charlie Knaggs, a desperate message that the district centre in the town of Naw Zad was being attacked by Taliban forces. A force of Paras is despatched, who were later replaced by Gurkhas. Soon Daoud was asking British troops to protect other towns and the Americans asked them to bolster the small force protecting the important Kajaki Dam. Step by step the Brits were forced into abandoning the initial plan of securing a relatively small area bounded by Camp Bastion, Geresh and Lashkar Gah in the south, and instead found their forces scattered thinly across half a dozen outposts which came under increasingly fierce attack.

Far from being a gentle peacekeeping and reconstruction exercise, the deployment was turning into a full scale war against the Taliban. Fairweather is brilliant at conveying the complex political cross-currents which led to the decisions, and the shambolic last-minute way they were carried out.

Will Pike led the deployment to the northern outpost of Sangin. As the Paras set about fortifying the district centre a delegation of town elders came and asked them to leave. They knew the Taliban would attack. They knew it would develop into a siege of attrition. They knew their town would be badly damaged. They were right on all three counts, but Pike had to turn them down. So much for listening to the locals, democracy etc. Instead of peace, the Brits brought war and destruction wherever they went.

Days later the Sangin district centre was hit, 3 killed 3 badly injured. If Butler had been in Camp Bastion maybe he’d have changed his mind but he was in Kabul where his job had evolved into trying to manage Governor Daoud and his master, Afghan president Karzai. So he overruled his junior officers’ concerns and the troops remained in Sangin in what developed into a relentless, daily barrage from the surrounding Taliban.

Already it was clear the critics had been right: a) the deployment to Afghanistan was too small; b) it had truckled to political pressure and spread its forces too thinly; c) it wasn’t going to be a peacekeeping deployment but a full-on conflict.

Chapter 23. Counterinsurgency in Iraq

Fairweather’s account of the revolution in military doctrine brought about by General David Petraeus who tries to re-orient the US Army approach from a ‘capture and kill the bad guys’ approach to a more imaginative deployment of counterinsurgency doctrine. The Americans referred to the British Army’s experience in the Malaya ’emergency’ i.e. how it handled an insurgency by revolutionary communist guerrillas. The main thing is to shift the goal from capturing or killing insurgents to winning over the general population by ensuring security. This shift in thinking is the central theme of Thomas E Ricks’s two books, Fiasco and The Gamble.

I believed all this until I read Frank Ledwidge’s devastating book, Losing Small Wars. There he points out two fundamental factors which the counterinsurgency proponents didn’t take into account. In Malaya, as later in Northern Ireland, a) there was one government whose fundamental legitimacy the majority of the population didn’t question; and there was b) an effective, impartial, well trained police force. Neither of these factors was present in Iraq or Afghanistan. On the contrary the ‘governments’ of both countries were deeply contested by large parts of the population, were widely seen as corrupt and parti pris; and the police forces in both countries were bywords for corruption and backsliding i.e. running away or turning their guns on their supposed Western allies whenever it came to a fight.

As the redeployment to Helmand began to be thought through, officers in Basra came under pressure to speed up the process of handing over responsibility to the Iraqi police and army. Only problem being, they were often corrupt and ineffective. Didn’t matter:

The army leadership was preparing to dispense with its commitment to create a competent Iraqi security force in the name of political expediency. (p.251)

Security in Basra was collapsing. The News of the World published a video of British soldiers beating detainees which triggered 48 rocket and mortars fired at the Abu Naji camp. Sectarian strife increased. A Sunni cleric was killed and new corpses turned up every day.

In January 2006 a further round of elections were held. Now, after weeks of horse trading, following the elections, Shia politician Nouri al-Maliki was finally appointed Prime Minister. He hated the British. British forces had arrested his grandfather in a 1920 Shia uprising. He saw the British presence as a continuation of its old imperial ambitions. On his first visit to Basra he told the British authorities he didn’t want to meet them.

Fairweather gives an illuminating account of the Ministry of Defence and army’s notorious problems with commissioning the right kit and equipment. While the army spent hundreds of millions on hi-tech, computerised gewgaws to fight the next world war, it neglected basic transport vehicles solid enough to resist improvised explosive devices.

Six month rotations ensured that just as each set of officers and men was coming to know the people and the job, it was rotated back to the UK and a completely new set came in. These were often led by a commanding officer determined to ignore everything his predecessor had done and implement his own pet theories. This was a recipe for inconsistency and incoherence. Fairweather cites the replacement of the bullish General Shireff with the scholarly General Jonathan Shaw in January 2007 (p.302).

He has an upsetting passage about post-traumatic stress disorder and the inadequate care the army takes of its psychiatrically damaged veterans. American studies suggest that 15% of veterans will suffer PTSD (p.256). The poor care for the physically wounded veterans at the Selly Oak hospital in Birmingham caused a scandal in the media (p.281). The scandal was to lead to the establishment of the extremely successful Help for Heroes charity (note, p.393).

The entire policy of withdrawing from south Iraq in order to redeploy to Afghanistan was thrown into doubt when the Brits handed over the main base in Muthanna province to the local security services then, a few days later, a crowd of several hundred assembled and stormed the base, the Iraqi security forces melting away as they were wont to do, whereupon the mob stripped the base of all the expensive equipment, looting all the arms and equipment the Americans had stocked it with. Farce (p.270).

In August British forces handed over Camp Abu Naji outside Amarah to local security forces. Within an hour word had spread, a few hours later a mob had assembled, and a few hours after that the crowd entered the base and comprehensively sacked and looted it. After spending £80 million trying to reconstruct the province the British were leaving it in the worst possible state. A ‘debacle’ and ‘fiasco’, the loss of Abu Naji brought the British army’s reputation among the Americans to a new low.

6 September 2006

The dreadful day when four Paras defending the Kajaki Dam in Helmand got caught in a minefield, one fatality, three terrible injuries and the heroism of Chinook pilot Mark Hammond who flew sorties not only to the dam, but to Sangin and Musa Qaleh, too (p.275). In fact it was only a week later that the elders of Musa Qaleh came to Butler and brokered a ceasefire deal between him and the Taliban. Both sides would withdraw and fighting would cease. An eerie quiet descended over the battletorn town which had been badly damaged during 6 months of fighting. The British talked about reconstruction but brought only destruction.

Meanwhile in Basra new commander, Genera Richard Shireff proposed a bold new plan of increasing his force and embarking on a policy of clearing the city neighbourhood by neighbourhood of the JAM, handing it over to Iraqi police to hold and then civilian experts to deliver high impact development projects. Of course none of this ever happened. He could never get enough British troops and the Iraqi police were useless. After some civilian contractors were killed Margaret Beckett ordered the entire DFID contingent to leave Basra Palace base and be evacuated to Kuwait.

Back to the story of Haider the interpreter. He has married his sweetheart, Nora, and had a baby. Now he is thunderstruck to be told by his sympathetic boss, William Kearney, that the security firm is pulling out of Basra. Haider is going to lose his job and become more exposed to the JAM thugs who want to kill him for working with the infidel.

Chapter 28 The Surge, 2007

General Petraeus and retired general Jack Keane lobbied and persuaded president Bush not to quit and withdraw from a ruined Iraq but to take a gamble and increase troop numbers, by 30,000, the famous ‘surge’. General Casey was replaced by Petraeus as commander in chief.

The so-called Surge coincided with the so-called Sunni Awakening which was when Sunni tribes finally sickened of being threatened and dominated by al Qaeda militias. Delicate negotiations persuaded many Sunni tribes to accept American money and support to take on the terrorist group.

Baghdad had now become the epicentre of the civil war between Sunni and Shia, with mass ethnic cleansing, 200 deaths a week, and concrete walls separating ethnic neighbourhoods. Fairweather mentions the role of British civilian and pacifist Emma Sky as an unlikely adviser to hulking American general Ray Ordieno (pages 292 to 296).

Detailed description of the negotiations initiated by British General Graeme Lamb and James Simonds to convert Sunni militia leader Abu Azzam over to the Coalition side, with a mixture of flattery, promises of jobs and money for his 1,000-strong militia. The central achievement of Emma Sky in making friends with a female member of Maliki’s cabinet, Basima al-Jadiri and from then onwards keeping lines of communication open between the coalition commander and stroppy Maliki (p.298).

The Brits had been working through the latter half of 2006 towards finally withdrawing from Basra, deceiving themselves about the readiness of the Iraqi security forces to take over, or that Shireff’s policy of clearing neighbourhoods was working. But just as the withdrawal began to be implemented the Americans were embarking on the exact opposite policy, bringing in more troops as part of their Surge. In this context British policy looked more than ever like running away.

The British were under pressure to look tough and so undertook daring missions, including seizing Jaish al-Mahdi leaders. At the same time they sought interlocutors to negotiate a peace with. Most important was to be the leader of Jaish al-Mahdi in Basra, Ahmed al-Fartosi, who they had arrested and imprisoned three years before, and whose arrest led to the reprisal kidnapping of the two SAS men.

The British made him a simple offer: call off militia attacks and in return the British would cease patrolling the city and release his imprisoned cadres on cohorts. The clincher was telling Fartosi he had to take the deal in order to get his men freed and enrolled in the security services before Iranian agents and politicians took over. Fartosi was Shia, fanatical Shia, he had taken money and arms from Iran – but drew the line at letting Iran take over his patch.

These are the kinds of subtleties or complexities created by ethnic, religious, tribal, warlord and gangland allegiances which the coalition failed to get to terms with. Emma Sky is described trying to persuade Ray Ordieno that he needed to stop lumping all opposition groups as al Qaeda or Ba’athists or ‘insurgents’ and learn to distinguish between them. Only then could the coalition figure out what they wanted and even start to find negotiated, political solutions to the chaos.

June 2007

Gordon Brown became Prime Minister after Tony Blair stepped down as Labour Party leader. According to Fairweather everyone in Whitehall and the military knew that Brown regarded Iraq as Blair’s folly and had no interest in throwing good money after bad. He wanted all British troops withdrawn as soon as reasonably possible. As always, politics. When the army staff told Brown cutting and running would infuriate the Americans Brown said ‘good’. In Britain, and further afield (in the European countries which were always against the war) it would draw a stark line between Brown and his predecessor, and win him kudos for standing up to the Yanks. Army planners at the British military command centre in Northwood drew up five withdrawal scenarios. Brown unhesitatingly chose the quickest (p.315).

Some top brass thought a rapid withdrawal would make the British public question the sacrifice made so far. But in the three months during which Blair had extended the British occupation to mollify the Americans, 11 more British soldiers had been killed. The opposite line was that the British had fought shoulder to shoulder with the Americans for four bloody years and enough was enough.

The Brits released Fartosi’s deputy, other detainees and complied with their side of the bargain to halt all patrols in Basra. However violent attacks continued, with relentless bombarding of the British HQ in Basra Palace. American command in Baghdad gave the British senior officers who came to explain their withdrawal timetable short shrift. As the Brits claimed that Basra’s police force was ready to enforce security, American officers laughed.

In August 2007 the deal with Fartosi began and he was given a small office in the the base prison complete with phone and fax machine. From here he organised a complete ceasefire and an uneasy calm fell over Basra. On 3 September the British commander handed over security governance to the Iraqi government general assigned the job, and 600 soldiers left Basra Palace in a convoy of Warriors, armoured cars, lorries piled high with office furniture. They drove the ten miles to Basra airport. The idea is a residual force would stay there for up to a year to continue to train Iraqi army and police force. The JAM militia held wild celebrations at the ‘liberation’ of their city.

Story of Haider the interpreter, continued

Since the start of the year a number of interpreters had been executed by the militias. Terrifying story of him attending his brother-in-law’s wedding procession of twenty or so cars when it was intercepted by trucks with no plates, armed men leapt out, ran across to the car which contained Haider and his wife but grabbed Nora’s cousin by mistake, hauled him out of the car, threw him in the trucks, and roared off while the women screamed and wept. Next day the cousin’s corpse is found with a scrap of paper telling Haider to ring a mobile phone number. Haider’s wife’s uncle, Ali, arranges for him to flee to Iran with a fake passport and a little money. Then the militiamen kidnap Ali and call Haider, saying he must return or Ali will be murdered.

Haider makes a plan, to return to Basra, collect his family and go to the British base. Gordon Brown had announced a fast track visa process for Iraqi interpreters. He takes a minivan cab and collects his wife, mother, sister and three brothers but when they get to the British base, security won’t let them through.

Anyway, it turns into a real odyssey. They walk to a gas station where an old geezer has a taxi. Haider tells them they’re refugees and the old guy takes them home and lets them sleep in his apartment. But next morning he starts getting suspicious. Haider’s contact inside the British base tells him the precise paperwork he needs, but it involves getting an old style Iraqi passport which will take ages.

Haider has a brainwave and rings up a doctor he knew at medical school. Reluctantly, the doctor agrees to house them all in a spare room in his clinic, knowing he’s risking reprisals from the militia. Haider has a phone so he rings his old boss and friend William Kearney. Kearney jumps into action ringing round contacts to get Haider’s paperwork approved asap. He commissions a journalist to write a piece about the plight of interpreters and he even – and at this point we start to realise why we’ve been hearing so much about this poor man – arranges for Haider to do an interview with Radio 4’s Today programme, from the spare room at the clinic where he’s in hiding. Atmosphere of Anne Frank’s loft. Every time they heard footsteps in the corridor they froze in fear.

There are more hurdles to jump through, judges to be bribed, paperwork to be secured, relations pressed into running round the city getting the right documents. After a week they take another cab to the British base but Haider is now told that his brothers and sister aren’t eligible. He loses his rag.

When the British had needed him he had risked his life, but when he needed their help all he got was red tape. (p.326)

And now, 16 years later, the same treatment dished out to Afghan interpreters fleeing the Taliban. What a disgraceful, disgusting country Britain is.

Abandoning Basra

So the British abandoned Basra and the Shia militia took over, quickly intimidating the Iraqi police into staying in their stations, while black hooded armed men patrolled the streets, hitting women who weren’t properly covered and embarking on a campaign of murder and extortion. The Iraqi Way. A British officer, Colonel Andy Bristow, helps the new Iraqi governor of Basra, General Mohan al-Faraji, but quickly realises the deal with Fartosi to allow us to leave in peace, effectively undermined the police i.e. bankrupted the whole reason for us being there in the first place. When Mohan found out the British had gone behind his back to do a deal with the head of the militia to release back onto the streets over 1,000 criminal detainees, he was apoplectic.

It was just the sort of double-dealing the British were infamous for during their colonial days. (p.330)

On 31 December 2007 Fartosi himself was finally released from prison and within days (January 2008) war broke out between Jaish al-Mahdi and Mohan’s police force. The British base itself came under sustained mortar attack. The deal with Fartosi had failed. Not only that but the situation in Helmand was deteriorating, Ceasefires with local Taliban commanders had failed and the fighting was fiercer than ever. The army desperately needed to move its Basra forces to Helmand.

Fairweather then gives a typically detailed account of the way the new advisor to General Mohan, the Brit Colonel Richard Iron, conceives a plan to deliver a US-style surge but just to Basra. As mentor to Mohan he is outside the British chain of command and so a) gets Mohan to present it as a request to the Basra commander, something the Brits are meant to help with, b) schmoozes with the Americans in Baghdad who love it. Petraeus is won over and the Yanks begin making plans to send troops to help the meagre British presence from the air base.

BUT. At one of these co-ordination meetings everyone is stunned to learn that Prime Minister Nouri al-Malaki, having been briefed about it some weeks before, has taken the bull by the horns, and ordered his own surge in Basra, using native Iraqi troops!

Long story short: the Iraqi army took on the Jaish al-Mahdi in Basra and won! Over 6,000 Iraqi troops marched on Basra and Maliki himself flew in to supervise. To begin with it was chaos, with Iraqi units disintegrating or being blown to pieces by the heavily armed and motivated JAMsters. But the Americans couldn’t allow this to fail and so diverted troops and planes south to join the fight. The British administrator on the ground was humiliatingly denied entrance to meetings between Maliki and the American commander in chief. Maliki blamed the British for letting Basra sink to this level. The American military no longer trusted the Brits to do anything. Anyway, bureaucracy and reluctance to overturn the withdrawal plans meant only a handful of British officers were available. The Iraqis and Americans got on without them. National embarrassment. Humiliation.

Meanwhile Mohan was sacked and a new Iraqi commander put in place. American General Flynn told British brigade headquarters he’d flown in to stop the Brits failing again. Fairweather calls it ‘a damning indictment’ and laments ‘Britain’s battered reputation’. The senior British officers hung their heads in shame (p.337).

Then, to everyone’s surprise, there was a ceasefire. Unknown to the Brits or Yanks Maliki had sent delegations to the Iranian city of Qom to ask al-Sadr and the commander of the Iranian al-Quds Force to broker a ceasefire. Maliki knew that the Iranians had a vested interest in seeing him re-elected, as a moderate Shia Prime Minister, whereas defeat in Basra risked plunging the south into chaos and also triggering a resurgence of Sunni resistance. On balance it was in Iranian interests to rein in their proxies. So The message came back to Fartosi to cease fire. The guns fell silent. The Jaish al-Mahdi forces disappeared. Fartosi and other notorious leaders left Iraq altogether.

A few days later Iraqi forces occupied all the Jaish al-Mahdi strongholds. The insurgency in Basra was over and it had nothing to do with the Brits or the Americans but backroom deals between Middle Eastern players. In an ironic way it was a triumph because it showed that normal Middle Eastern politics, with all its corruption and sectarian horsetrading, had been restored.

But there was nothing the British C-in-C, Brigadier Julian Free, could do ‘to restore American faith in British competence’ (p.339).

Epilogue: summer 2011

In Fairweather’s view the retaking of Basra was a watershed. The Iraqi army then retook Amara (where Sergeant Danny Mills and his sniper platoon had such a torrid time in 2006) and routed Jaish al-Mahdi from Baghdad.

In the January 2009 provincial elections Maliki’s party defeated Sadrist politicians (i.e. politicians loyal to Muqtada al-Sadr). Maybe it was even some kind of democracy. A very corrupt form of democracy, Iraq sits on the fourth largest oil reserves in the world. Fortunes are made by politicians with fingers in the pie. Leaked documents and other evidence show the Iraqi police force settling back into old Saddam methods of arbitrary arrest and gruesome torture.

In Iraq’s March 2010 elections the slippery old chancer Ayad Allawi won the popular vote, with the backing of Saudi Arabia, because he is a Sunni Muslim. (On a simple geopolitical level, Iraqi politics are riddled with the rivalry between Sunni Saudi Arabia to the south and Shia Iran to the east). However, in the backroom horsetrading Iran leaned on Muqtada al-Sadr to get his supporters to support Maliki who therefore re-emerged as Prime Minister in November 2010 (serving till 2014).

Through the summer of 2009 the British troops left Basra airbase. In total more than 120,000 British soldiers served in Iraq. As many as 15% of them might be expected to suffer mental illness as a consequence i.e. 18,000. 179 British personnel died, 5,970 were injured. Best guesses are that in the region of 100,000 Iraqis lost their lives.

Fairweather’s figures are that the war cost roughly £1 billion a year, total about £8 billion. Fairweather injects a political note (remember he wrote for the Daily Telegraph, what is now a very right-wing newspaper):

As schools go unbuilt in the UK, hospitals close, and tens of thousands of teachers, nurses, soldiers and policemen lose their jobs, the Iraq war has become a symbol of the profligacy and waste of the New Labour government. (p.344)

As to Afghanistan, in 2009 the Americans were forced to intervene as the British, yet again, lost control of the situation, sending a surge of 30,000 US troops to retake the province from the resurgent Taliban. The economy is still dirt poor. And there is no educated middle class to provide administrators and politicians.

As of summer 2011, 374 British service personnel had died in Helmand, 1,608 had been injured, 493 seriously. More than 10,000 Afghans had died. Gordon Brown estimated the war cost Britain £10 billion.

And Haider the interpreter, the Iraqi who Fairweather uses as a kind of barometer of Britain’s failing efforts in Basra? At the time of writing he lived in Hull, in accommodation provided by the British government, with his wife and two children. He’d like to return to Iraq but is still scared to.

The blame

As you’d expect, Fairweather holds Tony Blair chiefly to account for committing Britain to two wars it couldn’t win – but he’s harsher on the army. Senior generals gave consistently poor advice and the army as a whole was guilty of institutional failings, most importantly it’s continually over-optimistic predictions, its wrong assessments of the situation in both Iraq and Afghanistan, its insistence it could carry out both deployments with what quickly became clear were inadequate men and resources. In both places they ignored the well-informed warnings of experts in the field.

Most tellingly, senior officials at the MoD and armed services have come to see war as a way of maintaining their budgets. Fairweather wonders if the fact that this is the only way the MoD can secure adequate funding explains why Britain’s armed forces have been in conflict almost continuously for the past 15 years.

Short-termism. All kinds of delusions led planners to think a 3-year deployment to Helmand would be enough. The average length of a counter-insurgency campaign is 14 years. Proper state building takes even longer. Either commit, or don’t intervene.

Summary

This is an outstanding chronological history of Britain’s deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. Fairweather not only explains the complex political and financial realities at work in the British government and the fraught relationship with our American ‘allies’, but switches scene and focus with extraordinary confidence.

He gives what must surely be definitive accounts of specific firefights and battles (his 5 pages describing the murder of the six military police is exemplary) but he is just as confident describing conversations between the top power players, be they Yanks like Rumsfeld, Rice and Bremer, or Brits like Blair, Brown and Campbell.

And his narrative introduces us to an extraordinarily wide range of named individuals through whose stories and eyes we get really insider insights into every aspect of the situation, from Brits appalled at decisions in Whitehall or the chaos of the CPA, through the civilian governors struggling to control their provinces, to the experiences of scores of officers and men involved in fierce firefights on the ground.

It’s a panoramic, encyclopedic account. It really is outstanding.

P.S. A study in ignorance

Seen from another angle, this excellent book a study in several types of stupidity and ignorance.