‘Everywhere I look, and most of the time I look, I see photographs.’

(Bert Hardy)

This is a lovely overview of the entire career of acclaimed English photographer Bert Hardy (1913 to 1995), responsible for some of the most iconic shots of British life in the mid-twentieth century.

The exhibition includes:

- 87 black-and-white prints

- two photos enlarged and pasted on the walls

- two display cases showing Hardy memorabilia such as front covers of Picture Post, letters and negatives, press passes and diaries, even his passport (!)

- and, off to one side, a darkened room showing a slideshow of his colour photos

There’s even a case displaying one of his cameras. All this stuff is loaned from the Bert Hardy archive, now held by Cardiff University, making what is probably as major a retrospective as we can expect for some time.

All the photos are brilliant. Hardy was a photographer of genius. Born into a working-class family in the shabby area around Elephant and Castle, Hardy was self-taught and, once he’d gotten his big break during the war – getting a gig to photograph conditions in London’s bomb shelters – he went on to have a very varied career indeed.

He was lucky enough to break into the profession as it was experiencing the peak of photojournalism. During the 1930s there’d been a revolution in photojournalism and press reporting. This was precipitated by the advent of new, high quality lightweight cameras such as the 35mm Leica, but also the popularity of new, often left-wing editorial perspectives, themselves driven by wide cultural awareness of the miserable poverty caused by the Great Depression at the start of the 30s. Thus the late 30s saw the heyday of ground-breaking photo-journals such as Life in the USA (founded 1936) and Picture Post in Britain (founded 1938).

Magazines like this pioneered the use of photography-led journalism, extended pictorial essays about society during the politically fraught and feverish 30s. Lead editor at Picture Post was Tom Hopkinson and it was Tom who gave Bert his big break.

Bert had left school at 14 (1927) and got a job as a lab assistant at the Central Photo Service where he slowly familiarised himself with all the technical aspects of the trade. He practiced by taking photos of friends and his extended family (he was the eldest of seven sibling). His first commercial work was when he took a photo of the ancient King George V riding in an open top carriage along Blackfriars Road in 1935, turned it into a postcard and sold 200 copies around his neighbourhood.

In 1936 he was given a job as photographer at the General Photographic Agency and began to get work published in the Daily Mirror, Daily Sketch and the photo magazine, Weekly Illustrated. In 1941 he applied for a job with the Picture Post and the editor, Tom Hopkinson, set him a challenge – to take photos of Londoners in the air raid shelters where, notoriously, no lights were allowed, obviously creating difficult conditions for someone using a 1930s camera.

In the event, Hardy’s photos were vivid, well-composed and atmospheric and Hopkinson gave him a staff job on Picture Post where he was to remain for the next sixteen years (until the magazine closed in 1957). So this story explains why one of the first sections of the exhibition is devoted to images from the war.

In 1942 he was recruited into the Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU) with the rank of sergeant. Three days after D-Day he joined the troops in Normandy and went on to document the Liberation of Paris (August 1944), the invasion of Germany (November 1944), the crossing of the Rhine (March 1945) and arrived at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp a few days after it was liberated by British troops (April 1945). (I wonder if he met the SAS soldiers who were the first to discover Belsen, as detailed in Ben Macintyre’s book ‘SAS: Rogue Heroes’). He was then sent with the AFPU to Singapore in the Far East, where he became Lord Mountbatten’s personal photographer – there are some striking photos of the devilishly handsome Earl – and where he remained until September 1946.

He went on to cover Cold War conflicts in Greece and Korea (where his shots of the amphibious landings at Inchon in 1950 won awards) and then post-colonial conflicts in Malaya, Kenya, Yemen and Cyprus. The Inchon photos on display here are thrilling, conveying a real sense of the danger and contingency.

As to the other conflicts, I was particularly struck by images of supposed Mau Mau rebels cooped up behind barbed wire, and a particularly poignant photo of a British soldier searching a tubby, scruffy old peasant leading a donkey in Cyprus. So stupid, wars; complete failures of intelligence, failures to negotiate sensible rational solutions to human quarrels. (For the Mau Mau rebellion from the African point of view, see my reviews of the novels of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.)

But it wasn’t all war: Bert went on photo assignments to an impressive roster of countries, photographing ordinary life in Thailand, Bali, Burma, and across Europe to Ireland, France, Spain and Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Poland and Yugoslavia. He also went to Botswana, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Nyasaland, Rhodesia, Sudan and Tibet. Wow. What a life for a poor boy from the Elephant and Castle.

Between these foreign forays he travelled widely in the UK, recording the grim living conditions of working class people in London, Glasgow, Belfast, Tyneside and Liverpool and, along the way, documenting social and cultural changes after the war. By the early 1950s his work had become so well known and acclaimed that he was offered a job on the bigger, richer Life magazine (which he turned down).

Display case showing front covers of photojournalism stories by Hardy along with other memorabilia. Photo by the author

In the 1950s Bert branched out to cover the glamour and glitz of London’s theatre land and visits by Hollywood stars. Just before Picture Post closed, Hardy took 15 photos of the Queen’s entrance into the Paris Opera on 8 April 1957, which were assembled into a photo-montage – there’s a case devoted to this elaborate magazine spread.

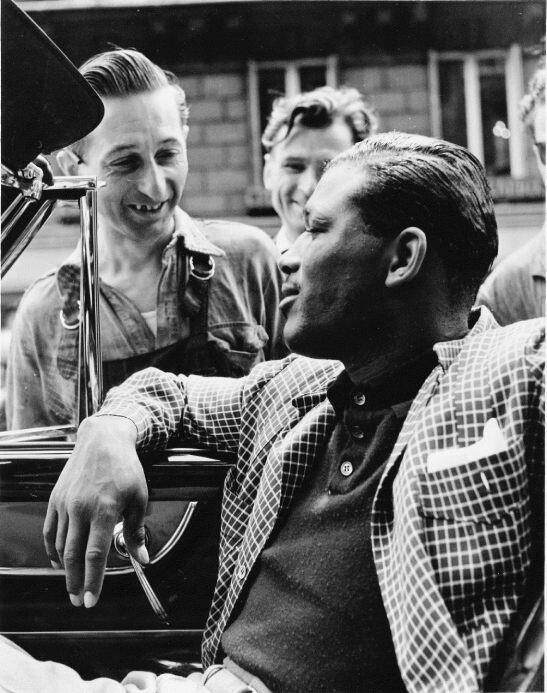

In parallel to the war, travel and glamour work, he also covered sporting events – the exhibition features shots of cycling (early on he had freelanced for Cycling magazine), wrestling and boxing stars.

Videos

Exhibition overview:

Interview with the curators:

Thoughts

Life just seemed so much more interesting and varied in those days. Britain’s cities look mired in crushing poverty, hardly anyone had a television (plenty didn’t have an inside toilet or hot water), but one aspect of this was a much greater diversity of people and dress and accent. Nowadays everyone dresses (more or less) the same and sounds the same and carries the same phones, and the shopping malls of London, Liverpool, Belfast or Glasgow all look depressingly the same with the same chain stores selling the same products. The world had much more genuine diversity and character back then.

But above and beyond learning a lot of detail about Bert Hardy’s career and individual commissions, the simple thought this exhibition prompts is that his photos need almost no explanation. They come from an era when photography and photojournalism was intended to be immediately comprehensible to a wide and popular audience, and by God, they are – incredibly direct and impactful.

The contrast with our own image-cluttered and intellectually verbose age is emphasised when you walk up a floor at the Photographers’ Gallery to see the four finalists for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2024. Each one of these requires a lengthy wall caption to introduce them and their aims and project plans and so on; and then each photograph requires a lot of explanation, some of them covering an entire A4 page.

Obviously all the Hardy shots do have wall labels giving their title and one in every three or four also has a caption giving a bit more detail and context – but none of them really need it. The whole point is that the images speak for themselves in a way that, interestingly, a lot of modern photography just doesn’t. Which means they are wonderfully democratic and accessible and inclusive, in a way that so much modern art and photography simply isn’t.

Cockney Life in the Elephant and Castle: ‘My goodness, my Guinness’ (1949) Photo by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Related link

- Bert Hardy: Photojournalism in War and Peace continues at the Photographers’ Gallery until 2 June 2024