He borrowed right- and left-handedly from all the customs of the country he knew and loved.

(Kim, Chapter 4)

Proper name: Kimball O’Hara

Nickname on the streets of Lahore: Little Friend of All The World

Kipling was dazzlingly prolific in prose and poetry but he only wrote three novels: ‘The Light That Failed’ (1891), ‘Captains Courageous’ (1897) and ‘Kim’ (1901). The first two are dubious works, problematic for a variety of reasons. By contrast ‘Kim’ is generally thought to be his masterpiece, the one significant, long-form work of prose which merits comparison with other novelists of his day, Hardy, Conrad, Wells, Foster, Bennett.

The basic idea is simple. From the start of his career Kipling enjoyed depicting working class characters, underdogs and low caste people, particularly soldiers in the British Empire’s imperial armies. These could be specific characters such as the soldiers three who appear in a dozen or more tales – Learoyd, Mulvaney and Ortheris – or the rough Portuguese seamen who crew the fishing schooner in Captains Courageous. Or when he captured the tone and voice of working class squaddies in the two sets of Barrack Room Ballads.

Kim pushes this tendency to a kind of extreme by focusing on a central character who is the orphan son of pretty much the poorest, lowest class in British India, his father (Kimball O’Hara) a former colour sergeant and later an employee of an Indian railway company, and Annie Shott (p.75), his mother, poor Irish, a former nanny in a colonel’s household.

When they both die young, Kim is orphaned, becoming ‘a poor white of the poorest’. But Kim wriggles free of caring relatives and interfering missionaries, of ‘societies and chaplains’, to become a street urchin, living on his wits, carrying out favours for countless merchants and shopkeepers, becoming so deeply tanned that strangers mistake him for a native Indian. His nickname among ordinary natives, shopkeepers, the local policemen and all who know him is ‘Little Friend of All The World’. He is ‘thoughtful, wise, and courteous; but something of a small imp’ (Chapter 4).

The whole novel is, then, a street-level depiction of Kipling’s beloved India of the 1890s. It starts in the Indian city of Lahore (now part of Pakistan), which is where Kipling himself was born and raised. Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, was the curator of the Lahore Museum. In numerous letters and journal entries, Kipling describes roaming the streets of the teeming, mysterious, often stinking muddy city from an early age, driven by incurable curiosity to seek out new experiences, sights, sounds and smells – as is his boy hero:

[Kim] meant to investigate further, precisely as he would have investigated a new building or a strange festival in Lahore city. (p.14)

A boy who can dodge over the roofs of Lahore city on a moonlight night, using every little patch and corner of darkness to discomfit his pursuer, is not likely to be checked by a line of well-trained soldiers. (p.73)

This is one reason for Kim’s lasting appeal. It is a vividly sensory description of life in 1890s India.

A second reason is Kipling’s extraordinary ability to depict the complex, multicultural strands of Indian life which, then as now, contained people of many faiths (Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain) speaking many languages (Hindi, Hindustani, Urdu, Punjabi, Tibetan, Persian and so on). Kipling’s text revels in religious, historical and linguistic complexity.

A third reason is the story’s appeal to children of all ages who want to roam free, who want to escape the trammels of parents, guardians, social services, school or (for adults) jobs, careers, family responsibilities, and roam wild and free through a never-ending phantasmagoria of exotic sights, sounds and adventures. It is an epitome of escapist fantasy.

Clipped language

A fourth and major element of the book is its style. I tried to analyse this in my essay on Kipling’s style. I tried to bring out the way Kipling doesn’t write like most other writers but has a very distinctive and idiosyncratic approach to the language. Above all it is very compressed and very allusive.

Compressed

By compressed I mean that he doesn’t spell things out in an ordinary accessible way. In his autobiography Kipling describes writing out a story in full, then going back later and deleting half the words. Then going back, again, and cutting even more words. At its worst this means that reading a Kipling text feels more like doing a cryptic crossword than reading clear, coherent prose.

Allusive

By allusive I mean his clipped prose continually alludes to or refers to specialist knowledge as if his readers should already know it, knowledge about native customs, beliefs, regional traditions, religious practices, types of clothing and so on, very often described in native Indian terminology which he explains once then expects you to remember for the rest of the book.

Mosaic style

I suppose there’s a third element which derives from the allusiveness, which is that Kipling lards his texts with quotations. But these emphatically aren’t the placid, civilised tags from French or Latin which other well-behaved late-Victorian writers use. Instead he creates a crazy mosaic text made up of Biblical quotes, schoolboy or military or technical slang, but above all, lots and lots and lots of native Indian words.

Understatement

Finally, there is his trademark understatement, which is another kind of allusiveness. Sometimes Kipling describes events or actions in such a radically understated way that you struggle to understand what he’s intending to say. All these elements sometimes make his prose quite a challenge to read.

Opening paragraph

Take the opening paragraph from Kim:

He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher – the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum. Who hold Zam-Zammah, that ‘fire-breathing dragon’, hold the Punjab, for the great green-bronze piece is always first of the conqueror’s loot.

A lot is going on here. Let’s try to analyse out the different types of verbal activity. First there are the names in a foreign language. Zam Zammah is mentioned in the first sentence with typical allusiveness, almost as if we’re expected to know what it means. Fortunately, Kipling translates it for us in the second sentence as meaning ‘fire-breathing dragon’ but, with typical understatement, he doesn’t really make it clear that he’s referring to a large, old-fashioned cannon. Similarly, he refers to the museum first off by its native name, ‘Ajaib-Gher’, which, admittedly, he then explains means the Wonder House, itself a local name for the Lahore Museum.

But the use of these non-English terms first, as the standard phrase, with the English translation coming second, immediately throws us into a foreign context, a foreignness which is then confirmed by mention of Lahore Museum, Kipling assuming his readers will know where Lahore is (north-west British India, now inside modern Pakistan).

There’s a similar expectation in the second sentence, that his readers will know where the Punjab is, but the real point of this sentence is to repeat the proverb about the Punjab. This is classic Kipling in five ways.

1. Mosaic text It is, in the broadest sense, one of the quotes or references I mentioned above, which make up so much of his text.

2. Cultural feel It ties into what I mentioned about the book’s skill at depicting the traditions, languages and mindsets of the many different cultures which inhabit his teeming multicultural India.

3. History Alongside the synchronic view of multiple cultures in the present, these two sentences also indicate a diachronic view of history. Kim’s world is the result of history, and not in a vague sense, but in a blunt Realpolitick kind of way: ‘The conqueror’s loot’ gives not only historical context but indicates the narrator’s cynical realistic attitude. The world Kim inhabits is one where winner takes all, as is made plain in the very next sentence:

There was some justification for Kim—he had kicked Lala Dinanath’s boy off the trunnions—since the English held the Punjab and Kim was English.

The imperialist suprematism of this is obvious. But just as typical is Kipling’s aggressively knowing reference to ‘trunnions’. Do you know what trunnions are without looking it up? (‘A pin or pivot on which something can be rotated or tilted. especially : either of two opposite gudgeons on which a cannon is swivelled’ – Mirriam-Webster dictionary)

4. Rebel Kim isn’t named in this opening paragraph, but his attitude is: ‘ in defiance of municipal orders’. He’s a rebel, a defier or ignorer of the law. (A notion not very subtle reinforced by the way his now-dead father is said to have served with ‘the Mavericks’, nickname for a regiment in the British Army which is entirely fictitious. A ‘maverick’ is ‘an unorthodox or independent-minded person.’)

5. Clipped prose Above all it demonstrates what I mean by compression, by Kipling’s inveterate habit of cutting, and then cutting again, his prose until it starts to read almost like a foreign language. ‘Who hold Zam-Zammah…hold the Punjab’ is clearly not standard English prose. There are two ways of fixing it: you could write :

‘Whoever holds Zam-Zammah…holds the Punjab’

Or, a bit more archaically:

‘They who hold Zam-Zammah…hold the Punjab’

Both would be acceptable grammatically correct English – but Kipling rejects both and has invented a new kind of prose. By deleting either ‘-ever’ (version 1) or ‘They’ (version 2) he makes the sentence significantly harder to parse (meaning ‘to resolve a sentence into its component parts and understand their syntactic roles’), harder to process.

This defining aspect of Kipling’s style makes many of his stories hard to read but here, in Kim, his allusive, clipped style meets an appropriate subject matter and the two weld. His dense, clipped, allusive, jargon-ridden, foreign word-strewn style finds a fitting match in a protagonist who is a young street urchin at home in half a dozen different cultures and languages, always in a hurry, always leaping onto the next thing, with a restless juvenile energy.

The never-still, restless bounding of the protagonist from one excitement to the next, like a hyper-active toddler, is perfectly dressed in Kipling’s restless, jumpy, allusive, densely compressed style.

It occurs to me that Kipling’s style has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This made it profoundly unsuitable for the telling of long sustained narratives with an interest in subtle psychological changes, such as we find in the novels of Thomas Hardy, Henry James, or Joseph Conrad. It explains why he wrote so many jumpy, nervy short stories and so few novels. But in this one, ADHD style met ADHD hero.

At one point, as Kim comes to recognise Colonel Creighton’s qualities, he thinks:

Here was a man after his own heart – a tortuous and indirect person playing a hidden game.

And the reader wonders whether this is a self-portrait of Kipling himself, his rather tortuous approach to English prose, his crabwise manner of conceiving and conveying his plots.

Archaic speech

Another element which adds to the sense of a foreign place and time, exotic setting and so on, is Kipling’s decision to render speech, often translated from one of the many Indian languages, in the style of the King James Bible. So, in the opening chapter, here is the Tibetan lama talking to the curator of the Lahore Museum:

‘We are both bound, thou and I, my brother. But I’ – [the lama] rose with a sweep of the soft thick drapery – ‘I go to cut myself free. Come also!’

‘I am bound,’ said the Curator. ‘But whither goest thou?’

It ought to feel arch and contrived, and maybe to some modern readers it does. But 1) Kipling uses it so consistently throughout the book that you soon get used to it and 2) if you buy into it, it is quite an effective way of conveying that they are talking a foreign language.

Indian speech

More obvious than the quirks of Kipling’s narrative voice is the fact that the overwhelming majority of the text is direct speech, and that is it packed to overflowing with native Indian words; rarely entire phrases, just individual words, which Kipling often includes a translation for within brackets. But lots and lots and lots of them.

‘And he is a stranger and a būt-parast (idolater),’ said Abdullah.

‘There was with me when I left the hills a chela (disciple) who begged for me as the Rule demands.’

‘Thy man is rather yagi (bad-tempered) than yogi (a holy man).’

‘Pardesi (a foreigner),’ Kim explained.

At first Kim had been minded to give the alarm – the long-drawn cho-or—choor! (thief! thief!) that sets the serai ablaze of nights.

‘My sister’s brother’s son is naik (corporal) in that regiment,’ said the Sikh craftsman quietly.

‘Three kos (six miles) to the westward runs the great road to Calcutta.’

And so on, many hundreds of times. The reader isn’t going to learn Hindi or Pashtun or Urdu from the book. On the other hand, you do begin to pick up a feel for the kinds of sounds these words make, a feel for the sound world of Indian languages.

The plot, chapters 1 to 9

Kim is the poor street urchin orphan of a Irish sergeant and a poor serving woman. With them dead, he makes a living as a scamp and jack of all trades on the teeming streets of Lahore.

The story opens with Kim playing with two other boys on a disused cannon outside the Lahore Museum when a strange figure walks into view. He turns out to be a lama, a holy man from Tibet who is searching for the River of Life aka the River of the Arrow (p.11), where, he has been promised, he will be able to free himself from the Wheel of Things.

The lama is shown round the museum by its curator (modelled on Kipling’s own father who was the first curator of the Lahore museum) who very kindly gives him his own good quality spectacles to replace the lama’s which are worn and scratched. (At the very end of the book the lama remembers the curator’s courtesy and kindness. I am touched by Kipling’s filial affection, p.225.)

The lama emerges into the heat and falls asleep in the shade of the big cannon. When he awakes, the boy Kim appears to him to be a vision, a presentiment, one sent to guide him. In a slight daze, the lama adopts Kim as his chela or disciple, telling him they must find the river in which he will be cleansed. For his part, Kim has a dim memory of his drunken father telling him his life will change when he meets a red bull on a green background. So he decides to fall in with the lama’s delusion, and act as his chela.

Out of general conversation emerges the idea that the river might by the mighty Ganges far away to the East. So step one is to catch a train East, to the town of Umballa. Near the train station is the Kashmir Serai. Here are shop and stables of the Pashtun horse trader Mahbub Ali, one of the many businessmen Kim survives by doing favours for. Kim takes the lama to go and see him, mainly because he wants to chivvy dinner out of him, and in this succeeds, Ali’s Balti servants feeding lama and boy. But learning of his journey, Ali gives Kim a message to deliver to a British officer in Umballa, a certain Colonel Creighton. Ali says it is about a white stallion he’s sold the officer and gives him a folded up piece of paper.

Kim knows there’s more to this than meets the eye but doesn’t know the full story. Because the narrator tells us that Ali is a British spy, codename C25 1B and the piece of greasy folded paper he gives Kim is a report from another operative, R17, and that it:

most scandalously betrayed the five confederated Kings, the sympathetic Northern Power, a Hindu banker in Peshawur, a firm of gun-makers in Belgium, and an important, semi-independent Mohammedan ruler to the south.

I.e. five independent Indian princes in the north of the country are friendly to the Russian Empire (the ‘sympathetic Northern Power’) and are in league with the others mentioned for some nefarious purpose, never clearly defined.

This is what moviemakers would later call the McGuffin, defined as ‘an object, event, or character in a film or story that serves to set and keep the plot in motion despite usually lacking intrinsic importance.’ Thus Kim has, without knowing it, been recruited into the so-called ‘Great Game’, the name given to the cold war which developed between the British Empire and the Russian Empire as the latter expanded its territory through Central Asia and tried to extend its influence into Persia and Afghanistan (and first mentioned in chapter 7, p.110).

I dealt with this in my review of Andrew Roberts’s biography of Lord Salisbury. From Salisbury’s view, as Prime Minister back in London, the British authorities in India were in a permanent state of hysterical over-reaction about Russia. It was paranoia about Russian interference in Afghanistan which had led to the Second Afghan War of 1878 to 1880, a wholly unnecessary and futile conflict. Salisbury was exasperated by Indian Viceroys who kept sending panic-stricken messages about the threat from Russia and demanding London to be more pro-active. Salisbury, wisely, thought Russian imperial expansion was more interested in annexing the central Asian republics than starting a war with Britain.

So the most important fact about the Great Game is that, despite the sweaty paranoia of Brits on the ground in India, a conflict between Russia and Britain over India never broke out. A huge amount of influence buying and espionage went on by both sides with, in the end, very little result.

Kipling was, of course, on the side of the Indian authorities and so the entire novel is set within the worldview of threatening Russian influence. In this respect it’s like a Cold War thriller or like Indiana Jones and the ever-present threat of the Nazis. A thriller needs baddies, ideally a network of baddies, Reds under the beds, Islamic terrorists everywhere etc, in order to create that enjoyably spooky sense of threat.

There’s a bit more spy stuff in that Ali knows he is being watched and all his messages are being opened and read. For him it is a stroke of luck that this street urchin who he uses to run errands has now decided on some cock and bull mission to help some lama head East, it suits him down to the ground to give him the secret message to deliver to Colonel Creighton in Umballa. And so, in a nice little scene, Ali, having divested himself of the folded up letter, goes along to one of his favourite prostitutes, ‘the Flower of Delight’, in a bordello, where he allows himself to be completely stoned on opium, knowing that the prostitute is a spy, knowing she is in league with foreign agents, knowing that, once he has passed out, these mystery men – ‘a smooth-faced Kashmiri pundit’ and ‘a sleek young gentleman from Delhi’ – will appear and thoroughly search his clothes and belongings, which is what they do. Not only that but they lift his keys and go to his stall/shop and search that very thoroughly – but are puzzled and frustrated to find nothing. Kim is pretending to be asleep, alongside the lama and the Balti servants, but sees all this taking place, and realises Ali is involved in something and that the message and piece of paper he’s to deliver to Creighton in Umballa are probably much more important than an innocuous message about a horse Ali has sold. (Later, in chapter 8 he tells Ali about this episode and how it was his first inkling that more was going on, pages 113 to 115.)

Next morning Kim helps the lama navigate a modern train station and get on a steam train and off they set, amid much local colour and much conversation on the train from the other travellers. One of the women takes to the lama and offers to put them up in the courtyard of the house in Umballa she’s heading to.

So they alight at Umballa and this woman very kindly sees them settled in her courtyard. But Kim explains he has to do an errand and makes his way to the luxury compound of this Creighton, clearly a man of influence. He comes out onto the veranda for a smoke, clearly a big social do is planned for that evening. His wife calls through the French windows so we learn his name is William Creighton.

a) Kim hiding in the shrubbery whispers that he’s there and he’s got a message from Ali. He throws the piece of folded paper onto the veranda where Creighton steps on it just as a servant enters. b) Kim then witnesses a carriage pulling up and another white man talking to Creighton, from the tone of his conversation his deputy. Then, apparently, the Commander in Chief of the Indian Army arrives and Kim watches them in conference, discussing this report, how it confirms their suspicions about the Russians etc. Kim doesn’t understand all the references but the reader realises they’re preparing for war, mention of two regiments being prepared, 8,000 men.

Characteristically, Creighton is made to say it isn’t a war, it’s a punishment (p.35). This is characteristically self serving, as if the British Empire alone has the right to adjudicate any other country’s behaviour and to allot punishment like a schoolmaster. It is also characteristically mendacious because, if this refers to the Second Afghan War of 1878 to 1880, then the Lord Salisbury book makes it clear that London regarded the whole thing as the fault of the aggressive policy of the British authorities on the ground, of the Viceroy overstepping his authority.

Thirdly, it is also very characteristic of Kipling’s sadistic streak which makes many of his stories unpleasant to read. This is a good example. There is a strong element of gloating in the narrator (Kipling)’s voice, as he looks forward to giving ‘the sympathetic Northern Power’ a damn good thrashing.

Kim returns to the compound of the friendly wife who gave shelter to the lama, and the next couple of chapters describe their onwards travels and the wide variety of Indian types they meet as they journey through India’s huge hot flatlands, then arrive at the legendary Grand Trunk Road.

‘Look! Brahmins and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims and potters – all the world going and coming. It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after a flood.’ And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India’s traffic for fifteen hundred miles—such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world. (p.51 cf p.56)

Lovely descriptions including their overnight stay at a parao or resting place where all types of Indians stop, make camp, light little fires. Here the lama is requested by a grand lady riding in a covered bullock wagon. She asks if the lama will bless her and accompany her on her mission to visit her son. the lama, in his simple way, agrees.

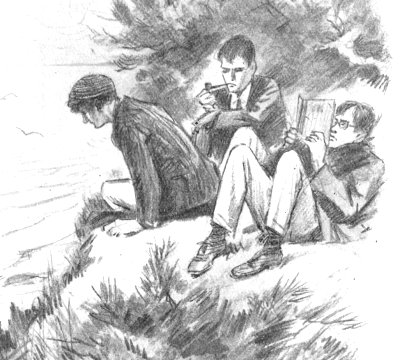

The next plot development is a few days later they are sheltering in a grove when they see advancing towards them a few men who peg out the flat land, followed by a horde who turn out to be a regiment of the British army. And their regimental flag is the image of a red bull on a green background. Kim is transfixed. It’s his father’s prophecy come true!

Once the compound is staked out and hundreds of tents erected, Kim sneaks past the guard and closer to spy what’s going on. But he is caught, after a scuffle, by the Anglican chaplain, Bennett (p.73). Having secured his prisoner, Bennett calls for the Catholic chaplain, Father Victor. In their different ways they interrogate Kim (Father Victor is by far the more sympathetic and forgiving). During the scuffle the necklace Kim has worn all his life with a little pouch of documents comes free and when the two priests examine them they are flabbergasted to discover that Kim is the orphan son of a former sergeant in their very regiment! (p.74) Well, what a coincidence – or kismet, as the Roman Catholic chaplain insists.

There’s a very long scene where the two priests detach Kim from the case of his lama, both of them very upset, until the lama concludes he was a fool to let himself become attached to things of this world, stands and disappears into the night.

Kim is given to the care of the drummer boys with a sergeant to guard and ensure he doesn’t try to escape. When Kim asks where the regiment is headed they say back to barracks but he contradicts them, telling them they will soon be heading off to ‘thee war’ as he pronounces it. Everyone laughs. But the next day the regiment does receive orders to move to the front (presumably up to the North-West Frontier with Afghanistan) and Bennett and Victor, in particular, are flabbergasted.

So they march back to the regimental barracks at Umballa. Here most of the fighting men entrain for the frontier and disappear, leaving the barracks half empty and echoing. Kim hates it. He hates the scratchy uniform they force him to wear, hates the ‘education’, the ‘discipline’ which consists of beatings, hates being humiliated by the teachers, and hates the other drummer boys he’s in class with. They are ignorant and vulgar, their stupidity indicated by the casual racism with which they insult the locals, in a way which is a kind of blasphemy to native-born Kim.

He manages to get a local letter writer to write a letter to Mahbub Ali and a few days later is strolling at the edge of the barracks when he is scooped up by a dark clothed native on a horse and whisked away. This is Ali. But in another far-fetched coincidence, when Ali has come to a halt and is discussing with Kim what to do with him, an English horseman rides alongside and who should it be, but Creighton!

He and Ali maintain a facade that he is simply a customer for Ali’s horses but Kim knows better, if not what’s really going on. Creighton accompanies Ali as he rides Kim back to the barracks. As they arrive at the main office, Father Victor comes out and recognised Creighton as Head of the British Ethnological Survey (p.94).

Creighton sits on the veranda and rather patronisingly listens to Father Victor spell out everything he knows about the boy, while watching Ali and Kim yarning under a nearby tree. The more Creighton hears, the more special he realises Kim is, and the more he begins to realise how he can be useful in his (Creighton’s) schemes. So he ‘charitably’ volunteers to the Father to personally supervise the passage of young Kim to St Xavier’s College in Lucknow (which Kim and Ali mock by mispronouncing ‘Nucklao’). The deal is done, the Colonel tells Kim to stay put and wait just three days, then he’ll come for him.

(Later on we discover that, surprisingly, the lama will pay the fees for the top notch private college, 300 rupees a year. This is because, again surprisingly, he is revealed to be the abbot of his lamasery back in Tibet (in Such-zen), and so has access to funds. It’s just that he chooses not to spend them on himself. But ‘Education is greatest blessing if of best sorts’, as he later writes in a letter to Kim.)

The way Ali and the Colonel speak loudly in the code of buying and selling horses, but really referring to information or about how to handle Kim, is amusing in its rather naive spyishness.

Three days later they travel south by train to Lucknow, the Colonel in First Class, Kim ill at ease in second. He preferred the sociability of third class when he travelled with the lama. He notices how white people have a special kind of detachment and loneliness.

Creighton gives him a cab to take to the Xavier College, but while cruising round this big city, Kim is astonished to see his lama sitting on a kerb. They are joyfully reunited. But Kim sticks to his promise and eventually arrives at the College.

Here, for the first time, the narrative ceases to be a moment-by-moment description and goes up a level to describe the passage of an entire term. Kim thrives. He is quick and canny. He learns to read and write in the company of three hundred other precocious youths. Kipling gives an extraordinarily knowledgeable overview of their classes and backgrounds:

They were sons of subordinate officials in the Railway, Telegraph, and Canal Services; of warrant-officers, sometimes retired and sometimes acting as commanders-in-chief to a feudatory Rajah’s army; of captains of the Indian Marine Government pensioners, planters, Presidency shopkeepers, and missionaries. A few were cadets of the old Eurasian houses that have taken strong root in Dhurrumtollah—Pereiras, De Souzas, and D’Silvas. Their parents could well have educated them in England, but they loved the school that had served their own youth, and generation followed sallow-hued generation at St Xavier’s. Their homes ranged from Howrah of the railway people to abandoned cantonments like Monghyr and Chunar; lost tea-gardens Shillong-way; villages where their fathers were large landholders in Oudh or the Deccan; Mission-stations a week from the nearest railway line; seaports a thousand miles south, facing the brazen Indian surf; and cinchona-plantations south of all. The mere story of their adventures, which to them were no adventures, on their road to and from school would have crisped a Western boy’s hair. They were used to jogging off alone through a hundred miles of jungle, where there was always the delightful chance of being delayed by tigers; but they would no more have bathed in the English Channel in an English August than their brothers across the world would have lain still while a leopard snuffed at their palanquin. There were boys of fifteen who had spent a day and a half on an islet in the middle of a flooded river, taking charge, as by right, of a camp of frantic pilgrims returning from a shrine. There were seniors who had requisitioned a chance-met Rajah’s elephant, in the name of St Francis Xavier, when the Rains once blotted out the cart-track that led to their father’s estate, and had all but lost the huge beast in a quicksand. There was a boy who, he said, and none doubted, had helped his father to beat off with rifles from the veranda a rush of Akas in the days when those head-hunters were bold against lonely plantations.

This is also by way of being in praise of the native-born, boys of white ancestry who are, nonetheless, born and bred in India and so a) lacking the nervous racism and racial supremacy of whites born and imported from England; and b) understanding the country, have a natural gift of command.

When the holidays come Kim goes walkabout, goes travelling round India, using the railway pass Creighton had given him. Creighton meets with Ali and bemoans this but Ali contradicts, saying it is good for one training to be a spy to keep up his talent for blending in; he’ll come back. Sure enough, a month later, Ali actually bumps into Kim on the Kalki road, they talk, Kim assures him he’s going back to Xavier’s for the new term.

There are a lot of chance, coincidental meetings in this narrative.

Ali invites him to join his team, giving him a thumb-stamped piece of paper which makes his servants accept him, where they’re gathered round the horse boxes to sleep for the night. The incident where Kim overhears the two agents who searched opium-zonked Ali back in chapter 3, now conspiring to assassinate him. Kim slips away and intercepts Ali as he’s riding back to his camp. Ali then cannily persuades the British station authorities that thieves are lying in wait in the sidings, so a British officer and policeman go in search and find them leading to a fight with guns and knives. Meanwhile Kim is back in his sleeping blanket, well pleased with his service to Ali. ‘Thy fate and mine seem as on one string’.

Ali takes Kim with him by train and road up to Simla, the Raj’s summer resort in the mountains. Here he is interviewed by Lurgan. Lurgan turns out to be an eccentric whose profession is jeweller – specifically, repairing worn out old gems and pearls – but he also keeps an old curiosity shop full of masks and bric-a-brac. He tests Kim’s nerve on the first night by revealing all the devil masks by lamplight then making him go sleep among them. Lurgan’s boy assistant of jealous of the new arrival and he and Kim fight, while Lurgan watches on, amused.

Kim stays with Lurgan for ten days, watching the variety of his customers, and playing games of memory in the evenings. We and Kim realise that it’s all part of his training to become a field agent.

At the end of the day, Kim and the Hindu boy…were expected to give a detailed account of all that they had seen and heard – their view of each man’s character, as shown in his face, talk, and manner, and their notions of his real errand.

They spend much time using make-up to adopt various disguises and Lurgan gives long lectures about the specific attributes of different tribes and castes and religious or ethnic groups.

The Hindu child played this game clumsily. That little mind, keen as an icicle where tally of jewels was concerned, could not temper itself to enter another’s soul; but a demon in Kim woke up and sang with joy as he put on the changing dresses, and changed speech and gesture therewith. (p.135)

‘Therewith’? Typical of Kipling’s crabbed, archaic prose style. Anyway, Kim comes to realise that Lurgan, too, is part of the network of operatives, part of the ‘Great Game’. When it’s time for Kim to finally go back to school, Lurgan tells him he’s welcome to return at the next holidays.

One of the visitors to the shop had been a Babu (a term of address for an educated man which, in English hands, became a sort of insult), a morbidly obese man who, Lurgan tells Kim, is one of the top 10 secret operatives in the country. His name is Hurree Chunder Mookerjee and (the narrator tells us) his agent number is R.17. If you’ve got a good memory (or can check an online text) you find that this is the same R.17 who produced the report that Mahbub Ali passed onto Kim to pass onto Creighton i.e. he really is a key operative.

Lurgan tells him there is a price on the Babu’s head as there is on the head of Mahbub Ali. Kim is boyishly excited, looking forward to the day when there is a price on his head!

This fat man is one of the members of the convoy which sets off four days later from Simla, heading back down into the plains. Before they split up Hurree gives Kim a betel box as reward for his achievements so far.

The narrative again moves up a level in order to skate through Kim’s school career. He is proficient in maths and practical knowledge, learns to play cricket, wins prizes. He is 14 years and ten months old, then fifteen years and eight months i.e. we are zipping forwards. Altogether Kim is 3 years at St Xavier’s College (p.139).

Remember the Tibetan lama? During this whole period he is offered hospitality at the Temple of Tirtankars in Benares, going on pilgrimages and travels, but always returning there, from where he and Kim exchange letters. (In fact we are told that the Curator of the Wonder House i.e. Lahore Museum, currently possesses a written account of all his journeyings.)

In holiday times he goes many journeys with Ali, who gets him to start doing small espionage tasks. Then he stays with Lurgan where he learns to recite the Koran, various spells and cures etc. Spycraft. The Colonel tests his ability with surveillance equipment and skill at making maps.

The past

There’s a very important paragraph on page 144. This says that a particular report Kim wrote (a survey of a town he visited with Ali):

was on hand a few years ago…but by now the pencil characters must be almost illegible.

This is important because it’s the first indication that all this happened some time ago, long enough ago for the pencil characters to have faded and become illegible. There’s been a few hints earlier but this really rams home the sense that all this happened in the historic past. Until this moment the reader had the sense it was happening right now, in the present.

Continued in Part Two.

Scenes and descriptions

Odd and clotted though Kipling’s prose often is, he strews the book with beautiful word paintings.

The teeming city

The hot and crowded bazaars blazed with light as they made their way through the press of all the races in Upper India, and the lama mooned through it like a man in a dream. It was his first experience of a large manufacturing city, and the crowded tram-car with its continually squealing brakes frightened him. Half pushed, half towed, he arrived at the high gate of the Kashmir Serai: that huge open square over against the railway station, surrounded with arched cloisters, where the camel and horse caravans put up on their return from Central Asia. Here were all manner of Northern folk, tending tethered ponies and kneeling camels; loading and unloading bales and bundles; drawing water for the evening meal at the creaking well-windlasses; piling grass before the shrieking, wild-eyed stallions; cuffing the surly caravan dogs; paying off camel-drivers; taking on new grooms; swearing, shouting, arguing, and chaffering in the packed square.

Lahore train station

The sleepers sprang to life, and the station filled with clamour and shoutings, cries of water and sweetmeat vendors, shouts of native policemen, and shrill yells of women gathering up their baskets, their families, and their husbands.

Portraits

The horse-trader, his deep, embroidered Bokhariot belt unloosed, was lying on a pair of silk carpet saddle-bags, pulling lazily at an immense silver hookah.

A black-bearded man, with a green shade over his eyes, sat at a table, and, one by one, with short, white hands, picked up globules of light from a tray before him, threaded them on a glancing silken string, and hummed to himself the while.

The room, with its dirty cushions and half-smoked hookahs, smelt abominably of stale tobacco. In one corner lay a huge and shapeless woman clad in greenish gauzes, and decked, brow, nose, ear, neck, wrist, arm, waist, and ankle with heavy native jewellery. When she turned it was like the clashing of copper pots. A lean cat in the balcony outside the window mewed hungrily.

India

All India is full of holy men stammering gospels in strange tongues; shaken and consumed in the fires of their own zeal; dreamers, babblers, and visionaries: as it has been from the beginning and will continue to the end.

The countryside

They followed the rutted and worn country road that wound across the flat between the great dark-green mango-groves, the line of the snowcapped Himalayas faint to the eastward. All India was at work in the fields, to the creaking of well-wheels, the shouting of ploughmen behind their cattle, and the clamour of the crows.

In the shade

The lama squatted under the shade of a mango, whose shadow played checkerwise over his face; the soldier sat stiffly on the pony; and Kim, making sure that there were no snakes, lay down in the crotch of the twisted roots. There was a drowsy buzz of small life in hot sunshine, a cooing of doves, and a sleepy drone of well-wheels across the fields.

Dusk in the countryside

By this time the sun was driving broad golden spokes through the lower branches of the mango-trees; the parakeets and doves were coming home in their hundreds; the chattering, grey-backed Seven Sisters, talking over the day’s adventures, walked back and forth in twos and threes almost under the feet of the travellers; and shufflings and scufflings in the branches showed that the bats were ready to go out on the night-picket. Swiftly the light gathered itself together, painted for an instant the faces and the cartwheels and the bullocks’ horns as red as blood. Then the night fell, changing the touch of the air, drawing a low, even haze, like a gossamer veil of blue, across the face of the country, and bringing out, keen and distinct, the smell of wood-smoke and cattle and the good scent of wheaten cakes cooked on ashes.

Simla by night

Together they set off through the mysterious dusk, full of the noises of a city below the hillside, and the breath of a cool wind in deodar-crowned Jakko, shouldering the stars. The house-lights, scattered on every level, made, as it were, a double firmament. Some were fixed, others belonged to the rickshaws of the careless, open-spoken English folk, going out to dinner.

Dawn

The diamond-bright dawn woke men and crows and bullocks together. Kim sat up and yawned, shook himself, and thrilled with delight. This was seeing the world in real truth; this was life as he would have it—bustling and shouting, the buckling of belts, and beating of bullocks and creaking of wheels, lighting of fires and cooking of food, and new sights at every turn of the approving eye. The morning mist swept off in a whorl of silver, the parrots shot away to some distant river in shrieking green hosts: all the well-wheels within ear-shot went to work. India was awake, and Kim was in the middle of it, more awake and more excited than anyone…

Educated to command the empire

One must never forget that one is a Sahib, and that some day, when examinations are passed, one will command natives. (p.107)

Background characters

I like counting and the book’s availability online makes it easy to make a list of secondary or background characters, who pop up as context and colour:

- Lala Dinanath’s boy

- half-caste woman who looks after Kim

- little Chota Lal

- Abdullah the sweetmeat-seller’s son

- Mahbub Ali, the horse-trader

- his Baltis (servants from Baltistan)

- the Flower of Delight, a prostitute

- a smooth-faced Kashmiri pundit, a spy

- a sleek young gentleman from Delhi, another spy

- a sleepy railway clerk

- a burly Sikh artisan

- the blueturbaned, well-to-do cultivator – a Hindu Jat from the rich Jullundur district

- his shrill wife

- a fat Hindu money-lender

- an Amritzar courtesan laden with head drapery

- a young Dogra soldier ‘of the Ludhiana Sikhs’, going south on leave

- a market-gardener, Arain by caste, growing vegetables and flowers for Umballa city

- the village headman, white-bearded and affable elder, used to entertaining strangers

- the ‘old withered’ retired soldier who stayed true during the Mutiny, ‘Rissaldar Sahib’

- the village priest

- a Punjabi constable on the Great Trunk Road

- ‘thin-legged, grey-bearded Ooryas from down country’

- ‘duffle-clad, felt-hatted hillmen of the North’

- the virtuous and high-born widow of Kulu or Saharunpore, travelling in the ruth or bullock cart attended by servants

- a dark, sallowish District Superintendent of Police, faultlessly uniformed (who jokes with the rich widow)

- the Reverend Arthur Bennett, Church of England chaplain of the Mavericks

- Father Victor, Catholic chaplain of the Mavericks

- at the barracks, the drummer-boy who had been hanging round him all the forenoon—a fat and freckled person of about fourteen

How Kim plays people

- Kim changed his tone promptly to match that altered voice.

- Kim knew what the faquirs of the Taksali Gate were like when they talked among themselves, and copied the very inflection of their lewd disciples.

- ‘Nay, what is it?’ Kim said, dropping into his most caressing and confidential tone—the one, he well knew, that few could resist.

- ‘True. That is true.’ Kim used the thoughtful, conciliatory tone of those who wish to draw confidences.

- ‘It is permitted,’ said Kim, and threw back the very tone.

- ‘God knows!’ said Kim cheerily. The tone might almost have deceived Mahbub Ali, but it failed entirely with the healer of sick pearls.

Kim’s character

- ‘No white man knows the land and the customs of the land as thou knowest.’ (The lama to Kim, p.79)

- ‘He was born in the land. He has friends. He goes where he chooses. He is a chabuk sawai (a sharp chap). It needs only to change his clothing, and in a twinkling he would be a low-caste Hindu boy.’ (p.93)

- ‘Thou wast born to be a breaker of hearts!’ [a houri painting Kim with walnut juice so he appears native]

- often in the past few months had caught himself thinking of the queer, silent, self-possessed boy. His evasion, of course, was the height of insolence, but it argued some resource and nerve. [Creighton thinking about Kim, p.109]

- ‘Colonel Sahib, only once in a thousand years is a horse born so well fitted for the game as this our colt. And we need men.’ (Mahbub Ali to Colonel Creighton describing Kim’s aptitude, p.142)

On the nature of a spy

In Simla the pearl jeweller Lurgan explains to Kim that:

‘From time to time, God causes men to be born – and thou art one of them – who have a lust to go abroad at the risk of their lives and discover news – today it may be of far-off things, tomorrow of some hidden mountain, and the next day of some near-by men who have done a foolishness against the State. These souls are very few; and of these few, not more than ten are of the best.’ (p.136)

Eighteen proverbs

The Norton edition includes a letter from Kipling to his favourite cousin, Margaret Burne-Jones, dated Lahore 28 November 1885, in which he answers her questions about life in India and, in doing so, summarises his own attitudes. He says the Indians are:

Touchy as children; obstinate as men; patient as the High Gods themselves; vicious as Devils but always loveable if you know how to take ’em. And so far as I know, the proper way to handle ’em is not by looking on ’em as ‘an excitable mass of barbarism’ (I speak for the Punjab only) or the ‘down trodden millions of Ind groaning under the heel of an alien and unsympathetic despotism,’ but as men with a language of their own which it is your business to understand; and proverbs which it is your business to quote (this is a land of proverbs) and byewords and allusions which it is your business to master; and feelings which it is your business to enter into and sympathise with. (Norton edition, page 269)

Well that explains his liberal use of proverbs throughout the text. They are just one of Kipling’s many strategies to create a sense of authenticity, a sense that we are inside Indian culture, listening to Indian people speaking in their own languages, using their own references, phrases, ideas and…proverbs.

- ‘Who hold Zam-Zammah, hold the Punjab’

- ‘Those who beg in silence starve in silence’

- ‘Let thy hair grow long and talk Punjabi’ (a Northern proverb)

- ‘Two arrows in the quiver are better than one; and three are better still’

- ‘For the sick cow a crow; for the sick man a Brahmin’

- ‘The husbands of the talkative have a great reward hereafter’

- ‘Never make friends with the Devil, a Monkey, or a Boy. No man knows what they will do next.’

- ‘Never speak to a white man till he is fed’

- ‘Trust a Brahmin before a snake, and a snake before an harlot, and an harlot before a Pathan’

- ‘I will change my faith and my bedding, but thou must pay for it’

- ‘Who looks for a rat in a frog pond’ (p.117)

- ‘When one can get blind-sides of a woman, a stallion, or a devil, why go round to invite a kick?’ (Ali, p.152)

- ‘Where there is no eye there is no caste,’ the Kamboh (p.165)

- ‘One priest always goes about to make another priest,’ the Kamboh (p.167)

- ‘Who goes to the hills goes to his mother.’ (p.192)

- ‘There are more ways of getting to a sweetheart than butting down a wall.’ (Hurree Babu, p.201)

- ‘So I should lose Delhi for the sake of a fish’

- ‘God made the Hare and the Bengali. What shame?’

Whiteness

The word ‘Sahib’ occurs 336 times, ‘white’ 121 times, ‘English’ 115 times.

The novel is very far from promoting white triumphalism. For sure, Colonel Creighton is depicted as a moral and administrative anchor, representing all that is stern and dutiful and wise in the Raj, but all the other white people come in for quite a lot of scrutiny or criticism.

Two types of whiteness are dramatised in the two chaplains, Bennett and Father Victor. Bennett, the only representative in the novel of the state religion, the Church of England, comes in for sustained criticism. He is thin, bony, aggressive, rude, completely unsympathetic to Kim, refuses to believe anything he says, would have offended the lama by giving him money to go away, until the Irishman Father Victor, far more sympathetically portrayed, intervenes to stop him. Kim and the lama remain the centre of the narrative and the reader’s sympathies. When Kim tells the lama that Bennett and Victor want to make him a Sahib like them, the lama strongly disapproves:

‘That is not well. These men follow desire and come to emptiness. Thou must not be of their sort.’

Later the lama described his loyalty to his monastery and his devotions and rather waspishly declares:

‘The Sahibs have not all this world’s wisdom.’

Kipling has the high-born widow, the woman from Kulu who adopts the lama, deliver trenchant criticism of different types of British administrator. After encountering an older, relaxed English official, she remarks:

‘These be the sort’ – she took a fine judicial tone, and stuffed her mouth with pan – ‘These be the sort to oversee justice. They know the land and the customs of the land. The others, all new from Europe, suckled by white women and learning our tongues from books, are worse than the pestilence. They do harm to Kings.’

Sahibs are often portrayed as stupid, racist, ignorant casually insulting. At St Xavier’s College Kim is warned not to treat the natives as lazy and stupid, the implication being that all too many of the colonial English do just that, damaging the reputation of the regime (p.121).

What makes the arrogant rudeness of so many of the whites harder for the natives to take, is that they are often so stupid themselves.

No man could be a fool who knew the language so intimately, who moved so gently and silently, and whose eyes were so different from the dull fat eyes of other Sahibs.

Mahbub Ali is a horse trader and has observed that, although most white men know next to nothing about horses, that doesn’t stop them from making all kinds of ignorant and sometimes insulting remarks:

That was the reason that Sahib after Sahib, rolling along in a stage-carriage, would stop and open talk. Some would even descend from their vehicles and feel the horses’ legs; asking inane questions, or, through sheer ignorance of the vernacular, grossly insulting the imperturbable trader.

Later, during Kim’s school years at the college, Ali remarks:

‘Son, I am wearied of that madrissah, where they take the best years of a man to teach him what he can only learn upon the Road. The folly of the Sahibs has neither top nor bottom.’ (p.145)

Ali is a reputable character, who grows in sympathy and status throughout the novel, so this is a credible view.

In other words, the creation of Kim as a character, and his easy way of mingling with numerous native Indian types – travellers, widows, soldiers, families, Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, traders, spies – enables Kipling to depict the entire range of white British presence in India from the outside, from the native point of view – and find it very wanting indeed. I wonder whether, when he started writing the book, Kipling realised just how much the creation of the boy outsider would enable him to mount quite such a sustained critique of Englishness, whiteness and Sahibdom.

White boys

White boys abound in the book but not at all as heroes, almost entirely as bad comparators with plucky Kim. The worst are the ‘drummer boys’ of Kim’s father’s regiment, depicted as fat, stupid, monosyllabic, lonely, bullying. They will never have Kim’s immersive knowledge of Indian cultures and street life. Again and again Kipling depicts them as ignorant, given to casual insults and racist abuse of the natives, while they themselves wouldn’t survive five minutes if thrown out into the real India. Compare and contrast with out plucky hero.

Now a bed among brickbats and ballast-refuse on a damp night, between overcrowded horses and unwashed Baltis, would not appeal to many white boys; but Kim was utterly happy. Change of scene, service, and surroundings were the breath of his little nostrils.

It’s true that in some of his summaries of Kim’s peers at Xavier’s, Kipling is sympathetic to the specific professions and jobs of their fathers. They are seen as doing good and worthy, unglamorous but necessary jobs for the regime. Nonetheless, they are all utterly eclipsed by the glamorous protagonist.

Stalky and Co.

I suppose it’s obvious, but these middle passages describing Kim’s schoolboy years at St Xavier’s College also bear direct comparison with the schoolboy stories collected in Stalky and Co which Kipling published a few years previously. There are reminiscences of the same snideness, the same facetious depiction of schoolmaster, the same sense of unpleasant schoolboy rivalries.

Talking of echoes, Kim also recalls one his two other novels, Captains Courageous from 1897, which is also about a schoolboy, in fact another fifteen-year-old – in this case Harvey Cheyne Jr, the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon.

Most of Kipling’s stories are about adults, obviously. But it tells you something about his not-quite-serious engagement with the world that four of Kipling’s five sustained narratives (the novels The Light That Failed, Captains Courageous and Kim, and the sequences of linked stories, The Jungle Book and Stalky and Co) are about boys.

The movie

Here’s the trailer for the 1950 movie version of the novel, starring the 14-year-old Dean Stockwell and Errol Flynn as Red Beard, Kim’s protector and British spy in the Great Game, a figure largely invented to make the film more dramatic.

Credit

Kim was serialised in Cassell’s Magazine from January to November 1901, and first published in book form by Macmillan & Co. Ltd in October 1901. All references are to the 2002 Norton Critical Edition edited by Zohreh T. Sullivan.