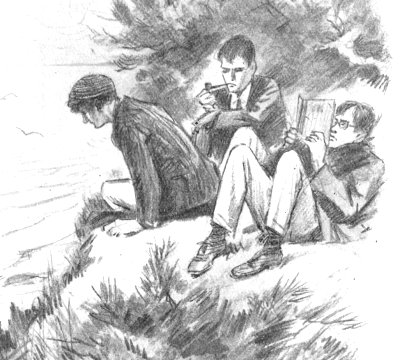

Stalky and Co is a collection of linked short stories about three boys – Stalky, Beetle, M’Turk – at a minor public school. The stories are closely based on Kipling’s own time at the United Services College at the picturesquely named village of Westward Ho! on the north Devon coast in the 1880s.

The school the three ‘lads’ attend is dedicated to preparing boys to take the Army Examinations for entry to Sandhurst and, ultimately, service in the British Empire.

The first edition of the book contained nine stories (listed in bold at the end of this review). Over the years Kipling added more tales, initially published in scattered magazines and collected in his regular short story collections, but eventually gathered into an expanded version of the book, The Complete Stalky and Co.

Initially I found this is the hardest Kipling book to read so far. The novels and short story collections are redeemed by spells of fine writing or uncanny elements of fantasy. But Stalky and Co sticks resolutely and stiflingly to its setting of nasty 5th and 6th formers at a minor public school, torturing each other, their teachers and any animal which crosses their path. There is no fantasy or uncanny, Kipling’s most appealing subject. There is little descriptive writing. Instead it is a large (300 pages) dose of concentrated public school japes described in a prose which echoes the schoolboy habits of quotation, slang, Latin tags and manly understatement. Some of the stories conveyed in such an elliptical style that they are quite hard to follow.

Sadism and brutality

There is lots of fighting, shooting cats and sparrows, boys cutting and bloodying each other, tormenting cattle with catapults, and an entire story devoted to the systematic torturing of two older boys, accused of bullying a lower form ‘fag’.

Kipling takes a disturbing relish in the punishment of the ‘bullies’, as in all the other examples of pain and cruelty. Throughout the stories he flaunts the boys’ brutality, testing if not taunting the reader; and many readers have flinched; many famous critics have been disgusted, not only at the violent incidents but at the ‘sophisticated Philistinism, a deliberate brutality of speech’ (Andrew Rutherford) which Kipling uses to describe it all.

The roots of Kipling’s sadism

Isabel Quigly speculates that the in-your-face style is wild over-compensation for Kipling’s anxiety at being an outsider at USC – a short-sighted poet destined for a career in journalism thrown into a school of toughs destined for the Army. No doubt.

I think it’s also part of Kipling’s taunting of liberals, the ignorant bourgeoisie and the English public generally, who he despises for failing to understand the sacrifices and the tough mind-set required to maintain the Empire which they so casually criticise, and from which they benefited so hugely.

In the final story old boys of the school remember the grown-up Stalky’s acts of derring-do on the North-West frontier, effectively redeeming all the previous tales of brutality by showing that is it necessary to be tough and hard if you’re going to run a damn Empire. It is no accident that the situation the grown-up Stalky and his men get into (getting surrounded by hostile natives) is caused by the ignorant civilian part of the Indian Administration, who foolishly declare the tribes in question to be ‘pacified’. It’s the poor bloody soldiers who have to clear up the resulting mess.

The ignorance of civilians – and especially MPs – about the hard work and sacrifice needed to keep the empire going is a standard theme throughout Kipling (see the short story One View of the Question or the poem Paget MP with its withering reference to ‘…the traveled idiots who misgovern the land…’).

Civilians ignorant of the reality of governing India are directly paralleled in Stalky by the parents who’ve sent their boys to this school and have no idea of the culture of permanent warfare, smoking, swearing and fighting which their poor babies endure (when small) and then perpetuate (when large).

Then there’s the psychological explanation, first mooted by Edmund Wilson in the 1940s, that Kipling never recovered from his horrifically miserable childhood, abandoned by his parents for 5 years to the beatings and bullying of a Portsmouth landlady and her violent son, all vividly depicted in his short story Baa Baa Black Sheep. That this childhood abuse led Kipling to a craven identification with power and authority at its most naked – if he’d suffered so much, then everyone else in his imaginative world had to put up with at least the same amount of torment and pain – a mindset which was then reinforced by the casual violence, the corporal punishment and the cult of manliness indoctrinated into him at his private school. It’s a persuasive theory…

Humiliation

Every one of the Stalky stories circles round the theme of humiliating locals, teachers or fellow pupils, then falling round laughing. It’s sometimes difficult to gauge: after all, Just William or St Trinians are about the same kind of thing – the endless war between pupils and teachers. But there’s something in the Kipling stories that pushes them just too far, makes them just too violent, just too sadistically humiliating to be funny…

Antinomianism

For someone who obsesses about the Law of the Jungle which must be obeyed, his three schoolboy heroes devote their entire time to undermining the rules and regs of the school they attend. This is done in the name of some higher law but, to the outsider, this higher law looks like the sanctimonious bullying of a self-congratulatory elite. Since Kipling’s purpose is to show how these schoolboys go on to apply what they learned at school to the running of the British Empire, the corollary writes itself…

Honesty

Well, at least Kipling doesn’t sugar coat it. This is what boys are often like. It’s as discomfiting a vision as his very unofficial depictions of the life of the Imperial elite at Simla as recorded in Plain Tales from the Hills. What makes it such an uncomfortable read is the way he himself clearly has no qualms about the brutalities and humiliations dealt out by his heroes. He is very clearly on their side as they hurt and outwit their enemies.

Hero worship

The other uncomfortable aspect is the schoolboys’ unquestioning hero-worship of the old boys who’ve gone on to become soldiers and serve the Empire and periodically return to the school to heroes’ welcomes. You could argue that the hero-worship – the whole school applauding their speeches then following them upstairs to dormitories to hear all about the exciting world of soldiery – is dramatically appropriate for boys in any era, and especially for a school preparing boys for the army. But there is no demarcation between characters and Kipling. Kipling slavishly worships his soldier heroes as avidly as any adolescent. To boys and military-minded men of the 1890s this must have seemed clean and virile.

But as the book went to press, the Boer War was just beginning (Stalky & Co was published on 6 October 1899; the Boers declared war on the British on 11 October). It was to be the biggest British military action between Waterloo and the Great War, one in which the British Army was humiliated and all but defeated, amid claims of incompetence and atrocity, very far from Kipling’s boyish ideals.

And beyond the Boers, hindsight casts a great shadow over Stalky because we know the boys, ‘ardent for some desperate glory’, who read the book in the early 1900s. were to have their ambitions more than met by the ‘awfully big adventure’ which was to break out in 1914…

Sense of humour

It’s hard to enjoy the earlier stories: the level of sadism or humiliation is too extreme (and the style is often so clipped and jocose as to be impenetrable). But the tone of the book lifts a little as it proceeds. It becomes less harsh, more good-humoured. The japes in The Last Term are almost ‘innocent’ – the trio a) pay a local girl to kiss a prefect in the street and ‘rag’ the entire prefect class as a result b) reset the words of a Latin exam in order to humiliate their Latin teacher. Made me laugh out loud. This is what makes Kipling so difficult to draw a bead on. There is contemptible, sadistic or racist material scattered throughout his writings. But there’s plenty that’s funny, grotesque, fantastic, interesting or inspired, as well.

The poem

A special note on the dedicatory poem, which takes its inspiration from a passage in the Biblical Wisdom of Sirach (44:1) that begins, ‘Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us.’

It works, in my opinion. Its purity of diction, its seriousness, is the purity of line of late Victorian and Edwardian heroic statuary. The central three lines of each stanza which repeat the same phrase with slight variations and end with the same rhyme word –

For their work continueth,

And their work continueth,

Broad and deep continueth,

give the poem a statuesque dignity. And some of its sentiments are noble. It praises the teachers who slaved away turning out the boys who went on to become the men who slave away in obscure corners of the Empire. The fact that these men may not all have been as heroic as Kipling suggests, may not all have been exemplars of selfless devotion, doesn’t take away from the nobility of the statue or of the ideal of service.

Stalky and Co stories online

Dedication (poem)

‘In Ambush’

Slaves of the Lamp: part 1

An Unsavoury Interlude

The Impressionists

The Moral Reformers

The United Idolaters (1926)

Regulus (1917)

A Little Prep.

The Flag of their Country

The Propagation of Knowledge (1926)

The Satisfaction of a Gentleman (1929)

The Last Term

Slaves of the Lamp: part 2