Wells was still in his early phase of creating genre-defining science fantasy stories when he wrote When The Sleeper Wakes, which was serialised in the Graphic magazine from January to May 1899.

It’s Wells’s version of the familiar trope of a man who falls asleep for an unnaturally long period of time and wakes up in a future where everything has changed, where a new civilisation is in place. (If you think about it, falling asleep and waking in the far future is a variation on the theme of time travel – only with no coming back!)

Invariably, the civilisation of the future is shown to have either solved or exacerbated whatever the author sees as the great social issues of his own day, so that the genre offers an author free rein to make prophecies and predictions, as well as working in as much social and political satire on their own times, as he or she wants.

Later, Wells became dissatisfied with the way he’d been forced to write When The Sleeper Wakes at top speed – he had been under pressure to complete another novel and to write a number of journalistic articles at the same time, and he was also ill during the writing of the second half. So, in 1910, for a new edition of his works, Wells rewrote the book and published it with a new title, The Sleeper Awakes. This is the version which is usually republished and which I’m reviewing here.

Wells had joined the left-wing Fabian Society in 1903 and had quickly become one of its most famous publicists and promoters. By 1910 his views on politics and society were well-known and the 1910 version of the book brings these explicitly political views out more clearly, as well as trying to sort out the many infelicities in the text of the novel. But in the prefaces to the 1921 and 1924 reprintings of the book, Wells continued to express dissatisfaction with the book, and this review will show some of the reasons why.

The plot

Part 1. Run-up

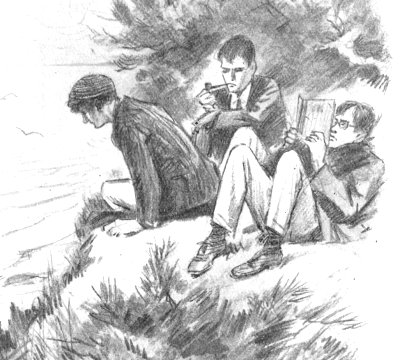

An artist named Isbister is wandering along the cliffs in Cornwall when he comes across Graham, a man contemplating suicide because he hasn’t been able to sleep for a week and feels like he’s going mad. While Isbister tries to talk sense to him, we are given evidence of Graham’s delirious frame of mind – he complains that he feels his mind spinning in an endless eddy, down, down, down.

Isbister takes Graham up to the cottage he’s renting, where he goes to make a drink, turns, and finds Graham sunk into a profound stupor, a cataleptic trance. His Long Sleep has begun.

In chapter two it is twenty years later and Isbister, older and wiser, discusses Graham’s case with a new character, Warming, a solicitor and Graham’s next of kin. We learn that Graham fell asleep in the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee (1897). Twenty years later it must be 1917, and Graham has been removed to the special ward of a hospital where he is sleeping on in a trance ‘unprecedented in medical history’.

We learn that Isbister has become a successful designer of adverts and posters, hundreds of which, as Warming points out, are now plastered all across the south coast, and has emigrated to America to pursue his career in advertising.

Meanwhile, Warming has invested in a new kind of road-surfacing. Irrelevant though this small talk appears, it later turns out to be important.

The sleeper wakes

In chapter three (there are 23 chapters) Graham awakes to find himself lying on a strange kind of pressure bed inside a case of green glass. He stumbles out of the bed to discover he is in a large antiseptic room. Attendants come running and then several men of command, notably:

a short, fat, and thickset beardless man, with aquiline nose and heavy neck and chin. Very thick black and slightly sloping eyebrows that almost met over his nose and overhung deep grey eyes, gave his face an oddly formidable expression. (Chapter 4. The Sound of Tumult)

This is Howard, who appears to be in charge.

The next few chapters are very confusing. Graham hears a roaring from a balcony overlooking a great concourse. When he goes out onto the balcony he sees an immense space dominated by modernist architecture, with some kind of covering over the sky, globes emanating uniform light, and the floor covered with ‘moving ways’, enormous ‘roads’ which are moving at speed carrying people along, and segmented so as to go round corners. There are what appear to be escalators coming up towards the level Graham finds himself on, and a great crowd surging towards him but held back by what look like policemen in red uniforms.

This impression of the immensity and complexity of the city of the future, conveyed in rather gaseous descriptions, will be the keynote of the novel.

Technology and design of the future

Howard tells Graham that he has slept for precisely 203 years. It is the year 2100 AD (Wells thus going a century better than the year 2000, which was the setting for Edward Bellamy’s famous fictional vision of the future, Looking Backward).

The sky is fenced off. Cities appear to exist under vast domes. Light is artificially created. Buildings are immense. The moving ways dominate what used to be called roads. Internally, rooms, halls and corridors are smooth and undecorated (except for occasional examples of an indecipherable script). Doorways open vertically and instantaneously.

Before Graham can do anything his guardians arrange for a ‘capillotomist’ to cut his hair and beard. Then a tailor takes quick measurements and, using a futuristic machine, prints out a perfectly-fitting contemporary outfit for Graham. He is given magic medicines which make him feel stronger, some small vials of liquid to drink and some in spray form.

In other words, it feels to me a lot like a set from the Star Trek series, smooth walls, endless corridors, bright different clothes, mystery medicines.

The Council

After Graham has blundered to the balcony and had a brief powerful glimpse of the scale of the city, the covered sky, the enormous buildings, and a huge crowd milling round the foot of his building, he is quickly hustled away, and down a series of corridors to a ‘safe room’. Along the way he glimpses a big hall with the ‘Council of Eight’ standing far away at a table beneath an immense statue of Atlas holding the world on his shoulder.

Ah yes, the Council. There’s always a Council of spooky older men wearing elaborate futuristic cloaks in this kind of story.

Confusion

The keynote of Graham’s experiences, and of the novel as a whole, is confusion. The people around him are very obviously thrown into confusion and panic by the fact that the Sleeper Has Awoken, but we and Graham don’t understand why for some time.

He is hustled away from the balcony room into the so-called Silent Rooms where he is kept by Howard for three days incommunicado, Howard refusing to answer any of Graham’s questions, resulting in Graham -and the reader – persisting in not having a clue what’s going on. Very confusing.

Then, suddenly and with no warning, there is a heroic ‘rescue’. Some kind of ‘resistance’ warriors drop down the ventilation shaft into Graham’s room and, while some attack the futuristic door to try and block it, others carry Graham back up the shaft.

They emerge onto the surface of the vast dome which covers the city and turns out to be extremely complex and uneven, lined by rows of windmills – presumably generating power – with gullies between the domes, as well as walkways and grilles and abrupt abysses with ledges on them. And it is snowing. Snow flies in his face blinding him, and builds up into drifts, blocking the panic-stricken progress of Graham and his guide who is trying to get him away from the Silent Room to safety before Howard and the Council discover he is missing.

It’s a straightforward chase scene of the kind you find in a thousand Hollywood movies. Still, it’s impressive of Wells to conceive a chase scene across the top of the dome covering a city of the future, in the snow. Vivid and cinematic.

Despite the action nature of the scene, Graham’s liberators find the time to explain that his cousin, Warming, cornered the market in a new way of surfacing roads which eventually put the railways out of business. The artist, Isbister, having moved to America, made a decisive investment in the early forms of cinema and television. Both lacked heirs and left their money in trust to the sleeping Graham, with trustees to administer the fund for charity. Over the past 200 years these trustees have built on the founding investment to buy up everything – everything – and now this London-based Council owns the world!

The entire world is like London, empty countryside surrounding super-cities, all ruled by Councils subservient to the Council. The Council banked on him never waking up and so created a complex cult of the Sleeper, the Master, who watches over society. For over a century they have ruled this highly stratified civilisation in his name!

Now he has woken up, the Council, and Howard their representative, have, unsurprisingly, been thrown into panic and confusion. The awakening came at a time of growing dissatisfaction among ‘the People’. It was an unlucky accident that Graham blundered out onto a public balcony within minutes of waking, and a crowd below saw him. Word is spreading that the sleeper has woken and this could have who knows what cataclysmic consequences.

According to his liberators the Council were discussing whether to drug Graham back into sleep or murder him or to hire an imposter. So that’s why they have ‘liberated’ him, and are hurrying him along to where ‘the People’ await.

The revolution

But barely has all this been explained than a Council airplane (the book was written before airplanes existed, through there was intense speculation and discussion in the press about how to build one) spots the fleeing pair and flies down firing the strange green guns of the future.

The liberator puts Graham on a seat attached to a zip wire running from an opening in the dome down to ground level and pushes him off, just as the plane comes round for another salvo of shots. Graham comes swooping along the high-wire over the heads of a vast crowd. The line is shot down but he is caught by the crowd and then takes part in a heroically confusing scene in which he seems to be taken up by an enormous crowd chanting his name, which is marching through the city of huge buildings and moving ways, marching on the great Council Building to overthrow the Council.

Graham is barely getting any sense of where he is and what’s going on before the crowd is itself ambushed by a large number of red-dressed police, who open fire and there is pandemonium.

Confusing action instead of clear exposition

There’s no denying that the narrative of this book is very confusing. It’s obviously a deliberate, creative decision by Wells, and he makes this perfectly clear in an extended reference to Julian West, the hero of Edward Bellamy’s best-selling science fiction novel, Looking Backward, which had appeared a decade earlier.

In that book, the hero awakes a hundred years hence into the orderly household of a doctor of the future, who calmly and sedately takes him through a long, logical explanation of the economic, political and cultural arrangements of the society of the future. It is more like a political textbook than a novel.

In fact, in most books about people waking up in the far future, the heroes are presented with a nice, clean, logical explanation of how the Future Society works.

Well’s chief aim in When The Sleeper Wakes seems to have been to work on the exact opposite assumption. What happens if you sleep for two hundred years and wake up amid mayhem, with absolutely no idea what’s going on and no-one to explain it to you?

In fact, if you wake up to riots and ambushes and civil war, with all sides claiming your allegiance? How can you possibly know which ‘side’ is right, or why there even are sides, or what you’re supposed to do?

The perversity of his experience came to him vividly. In actual fact he had made such a leap in time as romancers have imagined again and again. And that fact realised, he had been prepared. His mind had, as it were, seated itself for a spectacle. And no spectacle unfolded itself, but a great vague danger, unsympathetic shadows and veils of darkness. Somewhere through the labyrinthine obscurity his death sought him. Would he, after all, be killed before he saw? It might be that even at the next corner his destruction ambushed. A great desire to see, a great longing to know, arose in him.

He became fearful of corners. It seemed to him that there was safety in concealment. Where could he hide to be inconspicuous when the lights returned? At last he sat down upon a seat in a recess on one of the higher ways, conceiving he was alone there.

He squeezed his knuckles into his weary eyes. Suppose when he looked again he found the dark trough of parallel ways and that intolerable altitude of edifice gone. Suppose he were to discover the whole story of these last few days, the awakening, the shouting multitudes, the darkness and the fighting, a phantasmagoria, a new and more vivid sort of dream. It must be a dream; it was so inconsecutive, so reasonless. Why were the people fighting for him? Why should this saner world regard him as Owner and Master? (Chapter 10. The Battle of the Darkness)

So this sleeper awakes to find there is no polite doctor to talk him logically through the society of the future. Instead he is plunged into a social revolution which he doesn’t understand.

It’s an interesting idea, but it has one drawback. If the protagonist is confused, so too is the reader. Wells gets Howard, on the one hand, and the liberators, on the other, to throw out just enough hints to explain the situation to Graham (sort of, nearly). But the reader is left for three or four long, hectic chapters in a state of profound confusion.

Not only that but, in my opinion, Wells’s prose becomes confused. It sets out to mimic the panic of the unexpected rescue, the flight across the snowbound roof of the city, the panic-stricken glide down the high-wire down into the crowd, the confusion of a vast multitude marching chanting his name, the sudden ambush and red soldiers firing wildly into the crowd — but in doing so results in prose full of phrases describing vague forces, enormous spaces, shocks and detonations, huge crowds.

Now one of the appeals of The Island of Dr Moreau and The Invisible Man was the precision of their descriptions. You got a very accurate feel for what is happening. By contrast, Wells’s description of the vast spaces of this futuristic city, of its rearing architecture and machinery, is portentous but vague. It is hard to get a grasp of. Here is an excerpt describing the confused mob Graham has fallen among, as they march to overthrow the Council.

The hall was a vast and intricate space – galleries, balconies, broad spaces of amphitheatral steps, and great archways. Far away, high up, seemed the mouth of a huge passage full of struggling humanity. The whole multitude was swaying in congested masses. Individual figures sprang out of the tumult, impressed him momentarily, and lost definition again. Close to the platform swayed a beautiful fair woman, carried by three men, her hair across her face and brandishing a green staff. Next this group an old careworn man in blue canvas maintained his place in the crush with difficulty, and behind shouted a hairless face, a great cavity of toothless mouth. A voice called that enigmatical word ‘Ostrog’. All his impressions were vague save the massive emotion of that trampling song. The multitude were beating time with their feet – marking time, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp. The green weapons waved, flashed and slanted. Then he saw those nearest to him on a level space before the stage were marching in front of him, passing towards a great archway, shouting ‘To the Council!’ Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp. He raised his arm, and the roaring was redoubled. He remembered he had to shout ‘March!’ His mouth shaped inaudible heroic words. He waved his arm again and pointed to the archway, shouting ‘Onward! They were no longer marking time, they were marching; tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp. In that host were bearded men, old men, youths, fluttering robed bare-armed women, girls. Men and women of the new age! Rich robes, grey rags fluttered together in the whirl of their movement amidst the dominant blue. A monstrous black banner jerked its way to the right. He perceived a blue-clad negro, a shrivelled woman in yellow, then a group of tall fair-haired, white-faced, blue-clad men pushed theatrically past him. He noted two Chinamen. A tall, sallow, dark-haired, shining-eyed youth, white clad from top to toe, clambered up towards the platform shouting loyally, and sprang down again and receded, looking backward. Heads, shoulders, hands clutching weapons, all were swinging with those marching cadences. (Chapter 9. The People March)

It’s a judgement call as to whether you think this is wonderfully vivid writing which accurately conveys the feeling of being caught up in a panic-stricken crowd – or whether it is a relentless stream of confused and shapeless prose.

If you’re not focusing very hard it’s easy to get lost in these enormous, long, wordy paragraphs and have to go back to the last place you remember, to reread entire passages and find, yet again, that no very clear picture of the action is conveyed.

Ostrog shows him the storming of the Council

The marching crowd Graham’s with is ambushed by red-uniformed police who open fire. In the mayhem, Graham escapes, running miles away from the scene of what seems to be a massacre. From early on his liberators and then members of the crowd have told him that the revolt is being led by ‘Ostrog’. From other scared citizens he learns that Ostrog is based at a control centre for the city’s weather vanes (a form of wind power). He asks his way there, goes into the lobby, asks to see Ostrog and is eventually is let up to the main room where Ostrog is monitoring the revolution.

Ostrog shows him a futuristic TV screen on which they watch the mob storming the Council Citadel, from which Graham had been liberated only a few hours earlier. They watch the Council fight a last-ditch battle, having detonated the buildings which surround their citadel in order to clear a space. Ostrog and Graham watch all this on a screen. The revolution is being televised.

Part 2. A man of leisure

To cut a confusing story short, quite quickly the revolution is over and Ostrog takes control, settling the city back into law and order over the next few weeks. He is courteous and respectful to Graham and gets his number two, Lincoln, to fulfil the Sleeper’s every wish.

Now the revolution has been achieved and Ostrog is in control, Wells shows us that Graham is in fact a shallow dilettante. Having seen the airplane earlier, he tells Ostrog he wants to learn to fly. So he is taken up in a flying machine which circles London. From here he can see how the Wall of London rises sheer from the surrounding countryside like the wall of a medieval city. Beyond lie the ruins of suburbia and scattered empty houses.

It is important for Well’s vision that the entire population has been brought inside mega-cities where they can be completely controlled. Further south, Graham sees towns like Wareham and Eastbourne have been changed into single, vast skyscrapers. Here, as everywhere, all the scattered dwellings of individuals have been abandoned. Everyone lives in a regimented society.

The monoplane cruises across the south of England, then across the Channel and flies around Paris (where Graham sees the Eiffel Tower among the futuristic domes) before arriving back at one of the three vast landing platforms which dot south London.

The Flying Stages of London were collected together in an irregular crescent on the southern side of the river. They formed three groups of two each and retained the names of ancient suburban hills or villages. They were named in order, Roehampton, Wimbledon Park, Streatham, Norwood, Blackheath, and Shooter’s Hill. They were uniform structures rising high above the general roof surfaces. Each was about four thousand yards long and a thousand broad, and constructed of the compound of aluminum and iron that had replaced iron in architecture. Their higher tiers formed an openwork of girders through which lifts and staircases ascended. The upper surface was a uniform expanse, with portions – the starting carriers – that could be raised and were then able to run on very slightly inclined rails to the end of the fabric. (Chapter 16. The Monoplane)

On the flight back, Graham insists on taking over the controls, and, upon landing, hassles Lincoln into getting him a flying license so he can spend the next few days having special flying lessons, happy as a kid.

In the evenings Graham attends social events and mixes with the upper class of this future world. Here Wells indulges in satire directed at the values of his own times. The upper classes of the future are spoilt and insouciant. Everyone dresses more freely and casually than Graham’s late-Victorian peers. He meets a bishop and the poet laureate. He asks about the art and literature of the day (oil painting has been abandoned). He meets the Master Aeronaut, the Surveyor-General of the Public Schools, the managing director of the Antibilious Pill Department, the Black Labour Master, the daughter of the Manager of the Piggeries, who makes eyes at him – all characters invented so Wells can make a little social comedy at the expense of the pretensions of his own time, 1910.

However, these social scenes also have the function of dropping hints about the true nature of the society Graham has found himself in.

For example, the surveyor of public education has made it his task to prevent the lower classes thinking too much. The black labour master is in charge of black workers and soldiers in the colonies. Graham listens to them lightly discussing the way black colonial soldiers have been brought to Paris to suppress the ongoing rebellion there, with great violence, and it all makes him… uneasy…

Future sex

In the London of 2100 women have been ‘liberated’ in the sense that they all work and don’t spend much time on childcare. The women Graham meets at these parties consistently make eyes at him. In fact, Wells makes it as clear as he could (writing in 1910) that sex is much more casual in the future. We are told there are entire cities known as Pleasure Cities where, well, you can guess what happens there.

When Graham had been left alone in the Silent Rooms at the start of the story, he had picked up some cylindrical devices which proceeded to play ‘films’. Some appear to have been dramas, but it is as clear as Wells could make it that others were pornographic. He is shocked but the reader is impressed, as so often, by Wells’s prescience. Similarly, in those early scenes, Howard had appeared to offer him the services of prostitutes which, once he realised what was on offer, Graham quickly refused.

This must have been sailing close to the bounds of what was permissible in 1899.

A slender woman, less gaudily dressed than the others, a certain Helen Wotton, a niece of Ostrog’s, gets through to him at one of these parties and briefly manages to convey that ‘the People’ are still not happy, before Lincoln whisks him off to meet another notable.

Part 3. Reality hits home

Graham runs into Helen Wotton again, ‘in a little gallery that ran from the Wind-Vane Offices toward his state apartments’. She explains, with the passionate idealism of youth, that all her life she, and millions like her, have prayed for the sleeper to waken and liberate them from the repressive lives they live.

She surprises Graham by referring to the Victorian era as a golden age of liberty and freedom. He begins to put her right but she insists that back then the tyranny of the cities and the grip of Mammon was in its infancy. Now it has been perfected in a string of mega-cities covering the planet and entirely run by the rich, with up to a third of the population living underground, dressed in blue fatigues, and worked till they drop. As Helen explains:

‘This city – is a prison. Every city now is a prison. Mammon grips the key in his hand. Myriads, countless myriads, toil from the cradle to the grave. Is that right? Is that to be – for ever? Yes, far worse than in your time. All about us, beneath us, sorrow and pain. All the shallow delight of such life as you find about you, is separated by just a little from a life of wretchedness beyond any telling. Yes, the poor know it – they know they suffer. These countless multitudes who faced death for you two nights since – ! You owe your life to them.’

‘Yes,’ said Graham, slowly. ‘Yes. I owe my life to them.’

(Chapter 18. Graham Remembers)

Graham’s conscience is pricked. Who are ‘his people’? What do they expect of him? What is Ostrog actually doing? Now he thinks about it, in between flying planes and partying, whenever he meets Ostrog, the latter tells him the revolution has mostly achieved its goals and peace has been restored around the world (the world that the Council ruled in Graham’s name). But has it? Why does fighting rumble on in Paris?

So Graham goes to confront Ostrog. This is a big scene in which Ostrog delivers his Philosophy of the Overman. He tells Graham that his 19th century sentimentality about equality is out of date. This is the era of the Over-Man. The weak go to the wall. The race is purified.

‘The day of democracy is past,’ he said. ‘Past for ever. That day began with the bowmen of Creçy, it ended when marching infantry, when common men in masses ceased to win the battles of the world, when costly cannon, great ironclads, and strategic railways became the means of power. Today is the day of wealth. Wealth now is power as it never was power before – it commands earth and sea and sky. All power is for those who can handle wealth.’

(Chapter 19. Ostrog’s point of view)

As to the practical situation, in order to overthrow the Council, Ostrog had to make the people all kinds of promises about restructuring society. He reveals that it was he and his minions who created and taught the People the ‘Song of Revolt’ which they took up so enthusiastically. Now he is in power – now his coup d’etat has succeeded – Ostrog needs to put the people back in their place – hence the ongoing fighting in some cities, general strikes, workers on the street. ‘But don’t worry your pretty little head,’ he tells Graham. ‘I will soon have everything under control.’

They disagree. Ostrog is respectful but firm. Graham is frustrated and angry. They both go away harbouring their doubts. No good will come of this…

Part 4. Down among the proles

Determined to find out whether Helen is right, Graham dresses ‘in the costume of an inferior wind-vane official keeping holiday’, and, accompanied by the Japanese man-servant, Asano, who Ostrog has assigned to him, goes down among the proles.

This is a peculiar sequence. A combination of the visionary and the very familiar. It will come as no surprise that there are vast underground chambers beneath the city where the poor slave away. More surprising is the sequence about babies, where babies are separated at birth from their mothers and fed by machines which have the torsos and lactating breasts of women but screens for faces and metal pylons for legs.

Graham is appalled to witness a whole part of the underground covered in enormous and blatantly commercial hoardings advertising various Christian sects in unashamedly secular terms.

“Salvation on the First Floor and turn to the Right.” “Put your Money on your Maker.” “The Sharpest Conversion in London, Expert Operators! Look Slippy!” “What Christ would say to the Sleeper;—Join the Up-to-date Saints!” “Be a Christian—without hindrance to your present Occupation.” “All the Brightest Bishops on the Bench to-night and Prices as Usual.” “Brisk Blessings for Busy Business Men.”

He learns how individual living in individual houses has been swept away and the people live in huge dormitories and feed in vast canteens.

He also witnesses the oppressive ubiquity of trumpet-shaped loudspeakers of all sizes, some yards across, which broadcast an unremitting mixture of pro-government, morale-boosting propaganda, all prefaced by weird sound effects. They are called Babble Machines.

Another of these mechanisms screamed deafeningly and gave tongue in a shrill voice. ‘Yahaha, Yahah, Yap! Hear a live paper yelp! Live paper. Yaha! Shocking outrage in Paris. Yahahah! The Parisians exasperated by the black police to the pitch of assassination. Dreadful reprisals. Savage times come again. Blood! Blood! Yaha!’ The nearer Babble Machine hooted stupendously, ‘Galloop, Galloop,’ drowned the end of the sentence, and proceeded in a rather flatter note than before with novel comments on the horrors of disorder. ‘Law and order must be maintained,’ said the nearer Babble Machine. (Chapter 20 – In the City Ways)

There is much more in the same style. Asano guides him through the profoundly confusing and disorientating maze of tunnels, corridors, over bridges, onto balconies overlooking vast halls, up lifts, down escalators, all designed – I suppose – to give the exhausted reader a sense of the sheer stupefying scale of the city-state.

At last they come to the financial sector which is plastered, like the Christian sector, with huge billboards promoting all kinds of phoney get-rich-quick schemes and in whose halls overt, unashamed gambling and betting goes on.

Part 5. The second revolution

It is while he is in a sector devoted to jewel working that Graham and Asano hear the Babble Machines announcing that the Black Police are coming from South Africa to put down the remaining protesters in London. There is instant consternation and cries of protest from all around him. Graham had explicitly told Ostrog that, as Master, he did not want black troops brought to London.

The announcement that they are coming prompts another uprising, which Graham gets caught up in much as in the confusing early chapters. Amid proles yelling ‘Ostrog has betrayed us’ Graham and Asano struggle through the throng back to the half-ruined Council House. Here complicated repairs are underway with scaffolding and workmen everywhere fixing up the damage done by the first assault. Despite this, Ostrog has made it his base to run his world empire.

Graham gets admittance, takes lifts and escalators and the usual complicated paraphernalia up to the room with the huge statue of Atlas in it, where he confronts Ostrog, and they reprise their political and philosophical disagreement:

‘I believe in the people.’

‘Because you are an anachronism. You are a man out of the Past – an accident. You are Owner perhaps of the world. Nominally – legally. But you are not Master. You do not know enough to be Master.’ He glanced at Lincoln again. ‘I know now what you think – I can guess something of what you mean to do. Even now it is not too late to warn you. You dream of human equality – of some sort of socialistic order – you have all those worn-out dreams of the nineteenth century fresh and vivid in your mind, and you would rule this age that you do not understand.’ (Chapter 22 – The Struggle in the Council House)

The argument becomes physical and Graham finds himself wrestled to the floor by Lincoln and Ostrog’s other strongmen. Already Ostrog has a small bodyguard of yellow and black suited Africans at his side. However, some of the workmen repairing the Council chamber witness the fight and run to the rescue. Cue a general melée, in which Graham and Ostrog are knocked to the ground, roll around with their hands on each others’ throats and so on.

Finally, they are separated, Graham is hauled up and away by members of ‘the People’, who form a protective bodyguard around him and carry him out of the building, up stairs, down lifts and round the houses in the spatially disorientating way which characterises the whole book.

Then, in a scene which brilliantly anticipates the movies, Graham and the crowd watch from down at ground level a monoplane come swooping out of the sky and land on the half-ruined roof of the Council House. They see tiny figures moving in the half-exposed rooms, and then the monoplane pushes off from the roof and plummets vertically down, down, down in an apparently ruinous dive straight towards the ground – in a scene I’ve witnessed in countless adventure movies – before at the last minute catching enough wind to rise up and fly just over Graham’s head. Ostrog has escaped!

Part 6. Graham assumes control

Graham is taken by some of the crowd to a room where there are the gaping voicepieces of the phonograms and Babble Machines (an eerily prescient vision of the countless press conferences given by revolutionary leaders in front of banks of cameras and microphones) and Wells gives a good description of his utter confusion. He knows nothing about this world, nothing about politics, and has no idea what to say.

Then the slip of a girl – Helen Wotton – the one who leaked the news about the black troops being brought to London, comes into the room. She holds his hand. Graham is suffused with confidence and makes his big speech. He is on their side, he tells the microphones and ‘his people’ around the world. He will lay down his life for the People.

‘Charity and mercy,’ he floundered; ‘beauty and the love of beautiful things – effort and devotion! Give yourselves as I would give myself – as Christ gave Himself upon the Cross. It does not matter if you understand. It does not matter if you seem to fail. You know – in the core of your hearts you know. There is no promise, there is no security – nothing to go upon but Faith. There is no faith but faith – faith which is courage….

Things that he had long wished to believe, he found that he believed. He spoke gustily, in broken incomplete sentences, but with all his heart and strength, of this new faith within him. He spoke of the greatness of self-abnegation, of his belief in an immortal life of Humanity in which we live and move and have our being. His voice rose and fell, and the recording appliances hummed as he spoke, dim attendants watched him out of the shadow….

His sense of that silent spectator beside him sustained his sincerity. For a few glorious moments he was carried away; he felt no doubt of his heroic quality, no doubt of his heroic words, he had it all straight and plain. His eloquence limped no longer. And at last he made an end to speaking. ‘Here and now,’ he cried, ‘I make my will. All that is mine in the world I give to the people of the world. All that is mine in the world I give to the people of the world. To all of you. I give it to you, and myself I give to you. And as God wills to-night, I will live for you, or I will die.’

(Chapter 23. Graham Speaks His Word)

He, and we the reader, then have to wait, locked up in that little room confronted by banks of microphones, with only Helen to hold his hand, while reports trickle through of the fighting around the landing platforms, which is where the fleet of airplanes carrying the Africans is planning to land. They hear of – victory!

‘Victory?’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Graham. ‘Tell me! What?’

‘We have driven them out of the under galleries at Norwood, Streatham is afire and burning wildly, and Roehampton is ours. Ours!‘

(Chapter 24. While the Aeroplanes Were Coming)

It is difficult to know whether to laugh or to cry. The description of the fighting between Ostrog’s forces and the untrained, badly-equipped militias raised from the poor wards is fierce and intense. And yet the way it is reported back to the confused Graham in his room, holding onto Helen’s hand, seems absurd.

But although the people take one of the landing stages, his advisers explain that there are still too many planes in the enemy fleet, up to 100 of them, and that the other three landing bases are uncaptured, so they’ll be able to land.

It is then that Graham sees his destiny. All those days spent fooling around in an airplane will now bear fruit. He tells the small group of advisers he will go up in the monoplane and attack the enemy fleet, not expecting to defeat it, but to delay the planes long enough for the other landing pads to be taken by the people.

The advisers all point out this has never been done before, planes fighting in the air. Graham insists. Helen runs to him. He clutches her to his heaving breast. He must do it. It will save London. It is his destiny. She bows her head to the inevitable. He kisses the top of her head chastely.

And so the last five pages of the novel are an intensely imagined description of a fight in the air between the monoplane Graham is flying and a fleet of troop planes, a description of a technology which did not exist when Wells wrote about it.

Given this fact, he is amazingly prescient about the joy of flying, the sheer exhilaration of speeding through the high blue air, even if the combat technique Graham adopts – of ramming the enemy planes – wouldn’t have worked with the flimsy wood-and-cloth early planes which flew in the Great War.

Graham takes out two of the big troop carriers by ramming them and several others crash in trying to avoid him. He sees a monoplane taking off from the last platform, at Blackheath, and guesses it must be Ostrog. He sets off in fierce pursuit, dives and misses twice. Ostrog’s pilot is good. Then he sees the landing platforms of Shooter’s Hill and Norwood explode up into the air. They have been taken by the People and disabled for the landing flotilla. The People have won!

And then the shockwaves from the blasts hit his light monoplane, tipping it on its side so that it plummets out of the sky straight for the earth, and his last thought is of Helen. Bang. The end.

Thoughts

Quite a pell-mell farrago, isn’t it? A heady, fast-paced, confusing mish-mash of adventure story, sci-fi tropes, technological predictions, social prophecy, and ham-fisted psychology.

On the technology, Wells makes stunningly accurate predictions about hand-held moving picture devices, about phonograms, about propaganda blaring from loudspeakers, about wheeled vehicles, and, most strikingly, about the airplanes whose battle climaxes the novel.

The political idea of a liberal revolution which overthrows an autocracy but doesn’t change the exploitation of the working classes, and so needs to be supplemented by a second, proletarian, revolution, is straight out of revolutionary history.

The adventure trope describing the man who pitches up in an unknown society and ends up helping the poor and exploited overthrow their wicked rulers has all the power of myth and archetype.

The psychology of the sleeper is conveyed well enough, on the same general level as the rest of the book. It’s only with the sentimental relationship with young Helen, and especially the ‘it’s a far, far better thing I do’ climax where they cling passionately together before he turns and walks unflinchingly towards his certain doom – that you are forced to admit the whole thing is tripe.

These are all impressive, sometimes dazzling elements. But the main conclusion I took from the book was Wells’s ignorance of economics.

I’m really glad I recently read Edward Bellamy’s novel Looking Backward and made the effort to complete it, despite it being at some points oppressively boring. Because, despite this, it is a really thorough and penetrating analysis of how you would arrive at a feasible, enduring, classless and equal society.

Central is the idea of banning private enterprise, and having all production and distribution handled by the state. The two hundred pages it takes for Bellamy to work through all the logical consequences of banning capitalism, private enterprise and money, are long enough to make you really think about the basis of our current society – to force you to admit what capitalism means right down to the trivialest social interactions of human behaviour – and to make you really think through what changing it would actually mean, in practice.

Bellamy’s book has almost no plot but hugely impresses by its logic and thoroughness. I can see why it was a great success and even inspired a short-lived political party.

On the face of it Wells’s novel uses the same plot device – man falls asleep, wakes up in society of the distant future – but Wells couldn’t be more dissimilar in approach, content and impact. The comparison makes clear that Wells is diverted by science and technology from really thinking about the economic base of society. All the technological predictions are so much shiny flim-flam which hide the underlying lack of ideas.

It is all too easy to be bamboozled by Wells’s envisioning of kinematographs and phonograms and Babble Boxes, and hand-held film devices, and airplanes, and multi-wheeled vehicles, and ‘moving ways’ – to write long essays about his uncanny ability to predict technologies of the future – and to neglect the basic fact that his economic understanding is primitive to non-existent.

The People are oppressed, so our hero helps them rise up and overthrow their dictator. And what then? Who knows? Certainly not Wells. He is against oppression of the poor, and in favor of … what? ‘Equality’? ‘The People’? It isn’t enough.

Where Bellamy had acute economic analysis, Wells has men rushing across the domes of future cities being strafed by fighter planes. Where Bellamy worked through the logic of abolishing private enterprise, Wells has ambushes, fist fights, Pleasure Cities and babies brought up by robots. Where Bellamy calculated that abolishing competition between companies and the advertising such competition requires would result in net savings to society which could be redistributed to increase overall prosperity, Wells has rowdy satire about house-high billboards advertising Christianity-on-the-go or finance capitalism as literal casinos.

The thrill of the fast-paced adventure and the vivid action scenes, the steady stream of clever technological predictions, the primal archetypes of innocent good man confronting cynical manipulator, and of betrayed populace rising up against spoilt aristocrats – the combined result of all this garish phantasmagoria can easily overwhelm the reader and persuade her that something important and insightful is being said.

But it isn’t. Comparison with the logical economic and social analysis in Bellamy’s novel makes you realise what a showy huckster Wells was, and why, once the hysteria of the Great European Crisis of the 1930s ended in the ruinous grind of the Second World War, and when the world finally emerged into the cold light of day – the imaginative hold he’d exerted over generations of intellectuals and writers vanished like smoke because it turned out that he had nothing – of any permanent intellectual value – to offer.

Related link

Related reviews