Sight-seeing is the art of disappointment.

Introduction

In summer 1879, after an unhappy year of separation from his American lover, Fanny Osbourne, who had left him in Europe to return to her errant husband in California, Stevenson realised he had to confront her and force her to choose between her unfaithful husband, Sam, and himself, the impecunious Scots writer.

So he booked a berth on a steamer across the Atlantic from Glasgow to New York (a ten-day trip brilliantly described in The Amateur Emigrant), a few days later travelled the width of the continent by train from New York to San Francisco (as described in the more downbeat travelogue Across The Plains) and finally arrived at her doorstep in Monterey on Saturday 30 August.

But this wasn’t a fairy tale romance and negotiations with Fanny, and between Fanny and her husband, dragged on for months. In fact, Fanny didn’t manage to get a divorce from Sam until well into the next year, 1880, and she and Stevenson didn’t get married until 19 May 1880.

What to do next? Well some friends had mentioned an abandoned silver mining settlement at Calistoga, in the upper Napa Valley, which might be both picturesque material for a book and good for his health. The trip across the Atlantic, and then in a crowded unhygienic train across the continent, had severely weakened Stevenson, and it was only after his arrival in California that he had the first of many haemorrhages which were to dog the rest of his life. Fanny had barely married him before she found herself mothering an invalid.

So it was thought that Caligosta and the abandoned settlement of ‘Silverado’ would combine adventure and romance with healthy, restorative mountain air.

The Silverado Squatters

In a nutshell, they get a train north into the Napa Valley, then a horse-drawn wagon to a trading post, and then a wagon with a local Jewish trader and his family up to the remote Toll House Hotel, then walk up to the abandoned settlement. Far from being a leafy picturesque setting, Silverado turns out to be a handful of ruined sheds on a small flat outcrop on the edge of a foothill of the mighty Mount Saint Helena.

The place still stood as on the day it was deserted: a line of iron rails with a bifurcation; a truck in working order; a world of lumber, old wood, old iron; a blacksmith’s forge on one side, half buried in the leaves of dwarf madronas; and on the other, an old brown wooden house.

Robert, Fanny and her son, Lloyd, who had become Robert’s step-son, settle in to making the primitive wooden shack habitable. Obviously there’s no electricity, no toilet, there doesn’t appear even to be running water. As so often through all of Stevenson’s travel books I am awed at the extreme physical abasement he and his companions are prepared to put up with, in a ‘world of wreck and rust, splinter and rolling gravel, where for so many years no fire had smoked’.

Not a lot happens. Rather than give a synopsis, here are some highlights or themes.

Stevenson uses the telephone

I only saw Foss once, though, strange as it may sound, I have twice talked with him. He lives out of Calistoga, at a ranche called Fossville. One evening, after he was long gone home, I dropped into Cheeseborough’s, and was asked if I should like to speak with Mr. Foss. Supposing that the interview was impossible, and that I was merely called upon to subscribe the general sentiment, I boldly answered “Yes.” Next moment, I had one instrument at my ear, another at my mouth and found myself, with nothing in the world to say, conversing with a man several miles off among desolate hills. Foss rapidly and somewhat plaintively brought the conversation to an end; and he returned to his night’s grog at Fossville, while I strolled forth again on Calistoga high street. But it was an odd thing that here, on what we are accustomed to consider the very skirts of civilization, I should have used the telephone for the first time in my civilized career. So it goes in these young countries; telephones, and telegraphs, and newspapers, and advertisements running far ahead among the Indians and the grizzly bears.

Native Americans

Our driver gave me a lecture by the way on Californian trees — a thing I was much in need of, having fallen among painters who know the name of nothing, and Mexicans who know the name of nothing in English. He taught me the madrona, the manzanita, the buck-eye, the maple; he showed me the crested mountain quail; he showed me where some young redwoods were already spiring heavenwards from the ruins of the old; for in this district all had already perished: redwoods and redskins, the two noblest indigenous living things, alike condemned.

Californian wine

Calistoga, where he and Fanny head is in the Napa Valley. I’d vaguely heard the name because of the wines, but was surprised that Stevenson dedicates a whole chapter to ‘Napa Vine’, describing the experiments of the bold Americans with different grapes on different soils which ends with the surprising prediction

The smack of Californian earth shall linger on the palate of your grandson.

Being Scottish

Five thousand miles from home, Stevenson is surprised to find out just how homesick he feels, and indulges in one of his many meditations on the nature of Scottishness in a chapter titled ‘The Scot Abroad‘.

A few pages back, I wrote that a man belonged, in these days, to a variety of countries; but the old land is still the true love, the others are but pleasant infidelities. Scotland is indefinable; it has no unity except upon the map. Two languages, many dialects, innumerable forms of piety, and countless local patriotisms and prejudices, part us among ourselves more widely than the extreme east and west of that great continent of America. When I am at home, I feel a man from Glasgow to be something like a rival, a man from Barra to be more than half a foreigner. Yet let us meet in some far country, and, whether we hail from the braes of Manor or the braes of Mar, some ready-made affection joins us on the instant. It is not race. Look at us. One is Norse, one Celtic, and another Saxon. It is not community of tongue. We have it not among ourselves; and we have it almost to perfection, with English, or Irish, or American. It is no tie of faith, for we detest each other’s errors. And yet somewhere, deep down in the heart of each one of us, something yearns for the old land, and the old kindly people.

Of all mysteries of the human heart, this is perhaps the most inscrutable. There is no special loveliness in that gray country, with its rainy, sea-beat archipelago; its fields of dark mountains; its unsightly places, black with coal; its treeless, sour, unfriendly looking corn-lands; its quaint, gray, castled city, where the bells clash of a Sunday, and the wind squalls, and the salt showers fly and beat. I do not even know if I desire to live there; but let me hear, in some far land, a kindred voice sing out, “Oh, why left I my hame?” and it seems at once as if no beauty under the kind heavens, and no society of the wise and good, can repay me for my absence from my country. And though I think I would rather die elsewhere, yet in my heart of hearts I long to be buried among good Scots clods. I will say it fairly, it grows on me with every year: there are no stars so lovely as Edinburgh street-lamps. When I forget thee, auld Reekie, may my right hand forget its cunning!

Abandoned towns

One of the romantic aspects of America, when I was in my teens and reading hitch-hiking literature and watching 1970s movies, was the forlorn sense of abandonment, of windblown derelict settlements, of tumbleweed blowing through half-habited streets of boarded-up houses, which gave a powerful romantic feeling. It’s interesting to read Stevenson observing the origins of the phenomenon and explaining it.

One thing in this new country very particularly strikes a stranger, and that is the number of antiquities. Already there have been many cycles of population succeeding each other, and passing away and leaving behind them relics. These, standing on into changed times, strike the imagination as forcibly as any pyramid or feudal tower. The towns, like the vineyards, are experimentally founded: they grow great and prosper by passing occasions; and when the lode comes to an end, and the miners move elsewhere, the town remains behind them, like Palmyra in the desert. I suppose there are, in no country in the world, so many deserted towns as here in California.

Provisions

There is something singularly enticing in the idea of going, rent-free, into a ready-made house. And to the British merchant, sitting at home at ease, it may appear that, with such a roof over your head and a spring of clear water hard by, the whole problem of the squatter’s existence would be solved. Food, however, has yet to be considered, I will go as far as most people on tinned meats; some of the brightest moments of my life were passed over tinned mulli-gatawney in the cabin of a sixteen-ton schooner, storm-stayed in Portree Bay; but after suitable experiments, I pronounce authoritatively that man cannot live by tins alone. Fresh meat must be had on an occasion.

The Jew tyrant

Three chapters deal with the Russian Jewish merchant who takes charge of the Stevenson party and trucks them up to the abandoned mining settlement. Stevenson names him Mr Kelmar. He finds the Kelmars an attractive family and makes a number of direct comparisons between Jews and Scots, generally flattering to both.

Kelmar was the store-keeper, a Russian Jew, good-natured, in a very thriving way of business, and, on equal terms, one of the most serviceable of men. He also had something of the expression of a Scotch country elder, who, by some peculiarity, should chance to be a Hebrew. He had a projecting under lip, with which he continually smiled, or rather smirked. Mrs. Kelmar was a singularly kind woman; and the oldest son had quite a dark and romantic bearing, and might be heard on summer evenings playing sentimental airs on the violin.

Nonetheless it is a prominent feature of the book that through Kelmar’s activities Stevenson comes to the conclusion that many of the shop-keepers and traders in the region are Jews who very cannily lure trappers and miners into debt and into what, in effect, he calls debt slavery.

Stevenson is, presumably, painting what he sees – and here, as elsewhere, is astonishingly liberal and broad-minded for his age (consistently preferring Indians, Chinese and Mexicans to the unmannerly Americans and revoltingly crude emigrants). He likes the Kelmars and their undimmable high spirits.

Take them for all in all, few people have done my heart more good; they seemed so thoroughly entitled to happiness, and to enjoy it in so large a measure and so free from after-thought; almost they persuaded me to be a Jew.

Nonetheless, I can imagine the sheer amount of space devoted to Kelmar and the ultimately quite harsh criticism of his business practices, bothering some readers.

That all the people we had met were the slaves of Kelmar, though in various degrees of servitude; that we ourselves had been sent up the mountain in the interests of none but Kelmar; that the money we laid out, dollar by dollar, cent by cent, and through the hands of various intermediaries, should all hop ultimately into Kelmar’s till;—these were facts that we only grew to recognize in the course of time and by the accumulation of evidence… Even now, when the whole tyranny is plain to me, I cannot find it in my heart to be as angry as perhaps I should be with the Hebrew tyrant. The whole game of business is beggar my neighbour; and though perhaps that game looks uglier when played at such close quarters and on so small a scale, it is none the more intrinsically inhumane for that.

The sea fogs

The sun was still concealed below the opposite hilltops, though it was shining already, not twenty feet above my head, on our own mountain slope. But the scene, beyond a few near features, was entirely changed. Napa Valley was gone; gone were all the lower slopes and woody foothills of the range; and in their place, not a thousand feet below me, rolled a great level ocean. It was as though I had gone to bed the night before, safe in a nook of inland mountains, and had awakened in a bay upon the coast. I had seen these inundations from below; at Calistoga I had risen and gone abroad in the early morning, coughing and sneezing, under fathoms on fathoms of gray sea vapour, like a cloudy sky—a dull sight for the artist, and a painful experience for the invalid. But to sit aloft one’s self in the pure air and under the unclouded dome of heaven, and thus look down on the submergence of the valley, was strangely different and even delightful to the eyes. Far away were hilltops like little islands. Nearer, a smoky surf beat about the foot of precipices and poured into all the coves of these rough mountains. The colour of that fog ocean was a thing never to be forgotten. For an instant, among the Hebrides and just about sundown, I have seen something like it on the sea itself. But the white was not so opaline; nor was there, what surprisingly increased the effect, that breathless, crystal stillness over all. Even in its gentlest moods the salt sea travails, moaning among the weeds or lisping on the sand; but that vast fog ocean lay in a trance of silence, nor did the sweet air of the morning tremble with a sound…

The hunter

A humorous portrait of the phenomenally indolent self-important hunter, Irvine who the Toll House owners suggest could be a useful handyman for the Stevensons – but who turns out to be the exact opposite. It’s interesting to read Stevenson’s confident generalisation about this type of mountain / frontiersman, so different from the Hollywood stereotype of the all -American hero. A portrait of the class of people Stevenson tells us are referred to as ‘Poor Whites or Low-downers’.

There is quite a large race or class of people in America, for whom we scarcely seem to have a parallel in England. Of pure white blood, they are unknown or unrecognizable in towns; inhabit the fringe of settlements and the deep, quiet places of the country; rebellious to all labour, and pettily thievish, like the English gipsies; rustically ignorant, but with a touch of wood-lore and the dexterity of the savage. Whence they came is a moot point. At the time of the war, they poured north in crowds to escape the conscription; lived during summer on fruits, wild animals, and petty theft; and at the approach of winter, when these supplies failed, built great fires in the forest, and there died stoically by starvation. They are widely scattered, however, and easily recognized. Loutish, but not ill-looking, they will sit all day, swinging their legs on a field fence, the mind seemingly as devoid of all reflection as a Suffolk peasant’s, careless of politics, for the most part incapable of reading, but with a rebellious vanity and a strong sense of independence.

The toll house

A Dickensian satire on the extraordinary indolence of the Toll House and its inhabitants, Rufe, Mrs Rufe, the Chinese cook, the guests – Mr Corwin, Mr Jennings the engineer – and the timid village schoolma’am.

The Toll House, standing alone by the wayside under nodding pines, with its streamlet and water-tank; its backwoods, toll-bar, and well trodden croquet ground; the ostler standing by the stable door, chewing a straw; a glimpse of the Chinese cook in the back parts; and Mr. Hoddy in the bar, gravely alert and serviceable, and equally anxious to lend or borrow books;—dozed all day in the dusty sunshine, more than half asleep.

How, the modern reader wonders, did any of them survive or live? Where did the money come from? And what did they do all day? Chew straws apparently. Lounge on the veranda. Stare out over the panoramic mountain view, stunned into silence.

Crickets and humans

It’s one of the longer of Stevenson’s travel books but he is always excellent company, writing clearly and vividly, always alert to other people, to the scenery around him, to life. In fact this is the first of the five travel books I’ve read which has a chapter devoted to the natural world and the wildlife around them, systematically describing the trees, the wild flowers, the rather terrifying hosts of rattle snakes, and ending with a humorous conclusion about the ever-present sound of the crickets or cicadas.

Crickets were not wanting. I thought I could make out exactly four of them, each with a corner of his own, who used to make night musical at Silverado. In the matter of voice, they far excelled the birds, and their ringing whistle sounded from rock to rock, calling and replying the same thing, as in a meaningless opera. Thus, children in full health and spirits shout together, to the dismay of neighbours; and their idle, happy, deafening vociferations rise and fall, like the song of the crickets. I used to sit at night on the platform, and wonder why these creatures were so happy; and what was wrong with man that he also did not wind up his days with an hour or two of shouting.

What a good idea. What a typically boyish, impish and humorous conclusion.

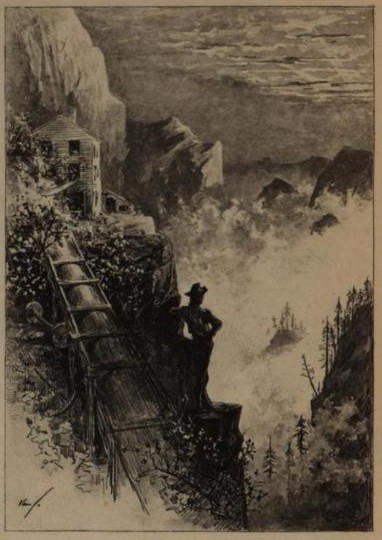

A fanciful illustration of the old miners’ bunkhouse on the narrow ledge of Silverado, a disused ore chute to the left, and our hero admiring a sea fog rolling in over the Napa Valley

Related links

- The Silverado Squatters on Project Gutenberg

- The Silverado Squatters Wikipedia article

- Stevenson in California

- Robert Louis Stevenson titles available online