(I believe you pronounce his surname Si-, to rhyme with sky, and -eed; Edward Si-eed.)

Orientalism created a big splash when it was published way back in 1978, nearly 50 years ago. It opened doorways into radical new ways of thinking about imperialist history and culture. It has gone on to be translated into more than 40 languages and had an immense influence right across the humanities. It’s a classic of cultural criticism.

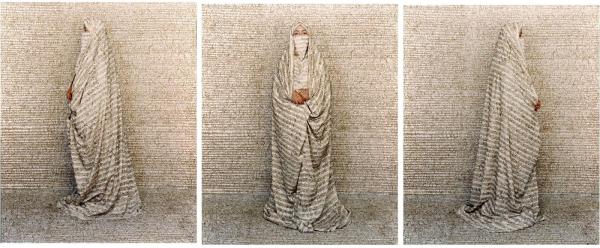

An example of its ongoing impact is the way the very first wall label which introduced the 2019 exhibition at the British Museum about the interplay between the Muslim world and Europe – Inspired by the East – quotes page one of Orientalism and then liberally applies Said’s perspectives throughout the rest of the show. It may nowadays be impossible to discuss the cultural and ideological aspects of Western imperialism, specifically as it affected the Middle East and India, without taking into account his perspective and sooner or later mentioning his name.

There are probably four ways of considering the book:

- The thesis.

- What the text actually says, its discussion of individual Orientalists (I try to give a summary in part 2 of this review).

- Its implications and influence.

- The practical political conclusions Said draws from his thesis.

Said’s thesis

Said’s thesis is relatively simple in outline and consists of a set of interlocking contentions:

The ‘West’ has always defined itself against the ‘East’. In earlier centuries, Europeans defined Christianity and Christendom partly by contrasting it with Islam and the Muslim world. In the imperial nineteenth century Europeans thought and conceived of themselves as energetic, dynamic, inventive and ‘advanced’ partly by comparing themselves with an ‘Orient’ which was slothful, decadent and ‘backward’.

But this entire notion of ‘the Orient’ is a creation, a fiction, a fantasy, created over centuries by Western scholars and writers and artists. It is a self-contained, self-referential image which is the product of Western fantasies and needs and bears little or no relationship to the confusing and complex reality of peoples and races and religions which actually inhabit the very varied territories which Europeans all-too-easily dismissed as ‘the Orient’.

These fantasies and fictions and fabrications about ‘the Orient’ were created by a sequence of Orientalist scholars, starting in the later 18th and continuing throughout the 19th centuries. Orientalism as a discipline began back in the 18th century with the first studies of Arabic, the Semitic languages and Sanskrit.

The bulk of Said’s text comprises portraits of, and analyses of the work of, the leading Orientalist scholars who, from the late eighteenth century onwards, founded and then developed what turned into an eventually enormous body of work, given the disciplinary name of Orientalism. This far-flung discipline, whose attitudes leeched into arts, sciences, anthropology, economics and so on, set out to categorise, inventorise, define, label, analyse and intellectually control every aspect of life and culture in ‘the Orient’.

This body of ‘knowledge’ ramified out through Western societies: it was packaged and distributed via newspapers, magazine articles, the new technology of photography, and informing, and in turned informed by, creative writing – novels and stories and poems about the ‘exotic East’ – and the arts – painting, sculpture and so on – to produce an immense, self-reinforcing, self-justifying network of verbal, textual, intellectual, ideological and artistic, popular, journalistic and political stereotypes and clichés about ‘the mysterious East’, and its supposedly sullen, childlike, passive, sensual and barbarous peoples.

Eventually this huge network of images and texts became received opinion, idées recues, hardened into ‘common sense’ about the Ottoman Empire, the Middle East and the Islamic world. And all of it – Said’s main and central point – was completely and utterly misleading.

Why did it thrive? How was it used? Said contends that this eventually huge set of preconceptions, this extensive set of prejudices, supported by leading scholars in the field, backed up by the narratives of various explorers and adventurers, given visual power in thousands of lush, late-Victorian paintings of the sensual, slothful, backward ‘Orient’, all this provided the discourse – the network of texts and images and ideas and phrases – which European rulers (of France and Britain in particular) invoked to justify invading, conquering, oppressing and exploiting those countries and peoples.

Orientalism justified empire. Orientalism provided the ideological, cultural, scientific and academic discourse which justified western colonialism.

When imperialist politicians, adventurers, soldiers or businessmen wrote or spoke to justify the imperial conquest and exploitation of the Middle East they quoted extensively from this storehouse of supposedly ‘objective’ academic studies, from supposedly ‘eye-witness’ accounts, from the widely diffused visual and verbal stereotypes and clichés of European artists, from what had become the received wisdom about ‘the Orient’ which ‘every schoolboy knows’ – in order to justify their imperial conquests and ongoing domination. But which were, in fact, the profoundly misleading creations of Orientalist scholars, ethnographers, writers, artists and so on.

The logical consequence of this sequence of arguments or worldview is that all Western narratives and images of the so-called ‘Orient’ produced during the 18th, 19th and indeed the first half of the twentieth centuries, are deeply compromised – because they all, wittingly or unwittingly, to a greater or lesser degree, helped to justify and rationalise the grotesque racism and unfair domination and economic exploitation of an entire region and all its peoples.

Orientalism is not only a positive doctrine about the Orient that exists at any one time in the West; it is also an influential academic tradition…as well as an area of concern defined by travellers, commercial interests, governments, military expeditions, readers of novels and accounts of exotic adventure, natural historians, and pilgrims to whom the Orient is a specific kind of knowledge about specific places, peoples and civilisations. (p.203)

Compromised learning

Said’s basic premise is that all knowledge, including academic knowledge, is not pure, objective truth, but highly constrained and shaped by the society, and people, which produced it.

My principle operating assumptions were – and continue to be –that fields of learning, as much as the works of even the most eccentric artist, are constrained and acted upon by society, by cultural traditions, by worldly circumstance, and by stabilising influences like schools, libraries, and governments; moreover, the both learned and imaginative writing are never free, but are limited in their imagery, assumptions, and intentions; and finally, that the advances made by a science like ‘Orientalism’ in its academic form are less objectively true than we like to think. (p.202)

Foucault

Said is a chronic name-dropper. He namechecks what has become the standard sophomore checklist of French and Continental literary and political theorists so very fashionable when the book was written. Thus he refers to Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci and Louis Althusser. It’s notable that these are all Marxist theoreticians and critics, because, at bottom, his project is not only to inject contemporary politics back into academic discourse, but specifically left-wing, anti-imperialist politics. But the figure Said refers to most often (fourteen times by my count) is the French historian and critical theorist, Michel Foucault.

This is because Said’s thesis piggybacks on Foucault’s notion of discourse. Foucault was a French historian who studied the institutions of prisons and madhouses (among other subjects) with a view to showing how the entire discourse around such institutions was designed to encapsulate and promote state power and control over citizens, and in that very Parisian perspective, over citizens’ bodies. So you could argue that Said is copying Foucault’s approach, lock, stock and two smoking barrels, and applying it to his own area of interest (hobby horse) the colonial Middle East.

Contents

Rather than give my own impressionistic view of a book, I generally find it more useful for readers to see the actual contents page. Then we can all see what we’re talking about. Here’s the table of contents. (I give a detailed summary of the actual contents of the book in part 2 of this review; and a summary of the long Preface and Afterword in a third review):

Chapter 1. The Scope of Orientalism

‘Draws a large circle around all the dimensions of the subject, both in terms of historical time and experiences and in terms of philosophical and political themes.’

1. Knowing the Oriental

2. Imaginative Geography and its Representations: Orientalising the Oriental

3. Projects

4. Crisis

Chapter 2. Orientalist Structures and Restructures

‘Attempts to trace the development of modern Orientalism by a broadly chronological description, and also by the description of a set of devices common to the work of important poets, artists and scholars.’

1. Redrawn frontiers, Redefined Issues, Secularised Religion

2. Silvestre de Sacy and Ernest Renan: Rational Anthropology and Philological Laboratory

3. Oriental Residence and Scholarship: The Requirements of Lexicography and Imagination

4. Pilgrims and Pilgrimages, British and French

Chapter 3. Orientalism Now

‘Begins where its predecessor left off at around 1870. This is the period of greatest colonial expansion into the Orient…the very last section characterises the shift from British and French to American hegemony. I attempt to sketch the present intellectual and social realities of Orientalism in the United States.’

1. Latent and Manifest Orientalism

2. Style, Expertise, Vision: Orientalism’s Wordliness

3. Modern Anglo-French Orientalism in Fullest Flower

4. The Latest Phase

Said’s personal position

Limiting his scope to the Middle East

On page 17 of the introduction Said says that, in order to avoid writing a book about ‘the Orient’ in its widest definition, he’s going to limit himself to writing about Islam and the Middle East. Sounds like a reasonable plan, the kind of defining of the boundaries of an intellectual project which you’d expect in any objective academic study. But the last pages of the Introduction give a whole new spin to this decision. On page 11 he writes that:

No production of knowledge in the human sciences can ever ignore or disclaim its author’s own circumstances.

He says this in order to broach his own relationship with the entire subject, then goes on to indulge in more pages of autobiography than you’d expect in a scholarly work. He tells us that the subject is in fact very, very close to his heart.

My own experience of these matters are in part what made me write this book. The life of an Arab Palestinian in the West [he’s obviously referring to himself], particularly in America, is disheartening. There exists here an almost unanimous consensus that politically he [Said] does not exist, and when it is allowed that he does, it is either as a nuisance or as an Oriental. The web of racism, cultural stereotypes, political imperialism, dehumanising ideology holding in the Arab or the Muslim is very strong indeed, and it is this web which every Palestinian has come to feel is his uniquely punishing destiny. It has made matters worse for him [i.e. Said] to remark that no person academically involved with the Near East – no Orientalist, that is – has ever in the United States culturally and politically identified himself wholeheartedly with the Arabs… (p.27)

So the book really is by way of being a very personal (and I use the word with knowing irony) crusade, coming out of his own personal experiences of discrimination and erasure, or, as he puts it in the 1994 Afterword to the book, from:

an extremely concrete history of personal loss and national disintegration. (p.338)

And written in the passionate hope that, by revealing the power structures behind the academic discipline of Orientalism in all its manifold forms, he can overthrow the false dichotomy between Orient and Occident, between East and West.

It’s a judgement call whether you find this frankness about his personal investment in the project admirably honest and an example of fessing up to the kind of personal position behind the text which his project sets out to expose in so many Orientalist scholars – or whether you think it reveals a highly partisan, parti pris perspective which invalidates his approach.

Said’s involvement in the Palestine-Israel problem overshadows the work

Said goes on to tie his detailed cultural analysis to a highly controversial contemporary political issue, namely the ever-fraught Israel-Palestine situation, as screwed up back in 1978 as it remains today. Crucially, his Introduction describes how this plays out in America culture, in academia and the media in the present day:

the struggle between the Arabs and Israeli Zionism, and its effects upon American Jews as well as upon liberal culture and the population at large (p.26)

In other words, Said explicitly ties his analysis of historical Orientalism to the bang up-to-date (albeit nearly 50 years old) political and cultural view of the Arab-Israeli conflict held inside American academia and the media and political establishments. This is obviously a perilous approach because the liveness of the current political debate around Israel-Palestine continually threatens to overshadow his academic, scholarly findings or ideas.

And Said was in fact far from being a distant academic viewer of the conflict. Said’s Wikipedia page tells us that from 1977 until 1991 he was a member of the Palestinian National Council (PNC) and deeply involved in negotiations to try and find a two-state solution to the Palestinian Problem.

1) It’s ironic that his book accuses all Orientalist scholars of being parti pris and biased, even if they don’t know it, while he himself is phenomenally biased and parti pris. But that’s a small point, and one he was perfectly aware of. He is perfectly clear about not really believing in the possibility of disinterested academic research:

I find the idea of strict scholarly work as disinterested and abstract hard to understand. (p.96)

2) More importantly, his political involvement threatens to a) distract from and b) overshadow Said’s entire project. In practice it meant he was forever getting dragged into stupid media squabbles, like the one featured on his Wikipedia page about him throwing a stone in Lebanon which managed to get blown up into press headlines about ‘The Professor of Terror’.

This is an American problem and links into the issues of the power of the Jewish lobby in Washington which is itself (as I understand it) linked to the even larger power of the fundamentalist Christian lobby in Washington, which (as I understand it) strongly supports the state of Israel for theological and eschatological reasons.

All I’m saying is that Said positions himself as someone who is bravely and pluckily bringing ‘politics’ into academia, revealing the power structures and political motivations behind an entire academic discipline, ‘Orientalism’, and good for him. But it’s a double-edged and very sharp sword. He who lives by politics dies by politics. Discussing radical political theory is relatively ‘safe’, as so many Marxist academics prove; but if you bring clarion calls about one of the most contentious issues in international affairs right into the heart of your academic work, and you shouldn’t be surprised if your political opponents will throw any mud to blacken your name.

Ironies

It’s a central irony of Said’s work that although he went to great lengths to expose the Islamophobia at the heart of the Orientalist project, he himself, despite being of Palestinian heritage, was not a Muslim, but had been raised a Christian.

In other words, all his writings about how Orientalists write about Islam without being inside it, without understanding it, without giving voices to Islam itself – the very same accusations could be brought against him.

From start to finish his book lambasts Westerners for speaking over the Orient, for never giving it a voice so it is a delicious irony that:

- There are no Muslim voices in his book – as far as I can tell he doesn’t quote one Arab or Muslim scholar anywhere, so he’s largely replicating a practice he is fiercely critical of.

- Said himself is not a Muslim – he lambasts various Western simplifications and demonisations of Islam with a strong sense of ownership and partisanship – but he himself comes from a completely different tradition.

I’m not saying either of these aspects negate his argument: but the whole thrust of the book is to teach us to pay more attention to the political aims and ideologies underlying apparently ‘objective’ academic texts, to question every author’s motives, to question the power structures they are part of and which permit their teaching, their research, their publishing. So these thoughts arise naturally from Said’s own promptings.

Problems and counter-arguments

Despite its astonishing success and the widespread adoption of its perspective throughout the humanities, Orientalism has many problems and issues.

Defining the ‘Orient’ and ‘Orientalism’

For a start, Said’s use of the word ‘Orient’ is extremely slippery. Sometimes he is referring just to the Middle East, sometimes he includes all of Muslim North Africa, sometimes he is referring to the entire Islamic world (which stretches to Indonesia in the Far East), sometimes he throws in India, the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, whichever suits him at the time.

In an ironic way Said’s definition(s) of Orientalism are as slippery and detached from reality as he says Orientalists’ discourse about ‘the Orient’ were.

One upshot of this is that you get right to the end of the book without ever reading a simple, definitive, usable definition of the central word. Here’s what the Etymological Dictionary has to say about ‘Orient’:

Late 14th century: ‘the direction east; the part of the horizon where the sun first appears,’ also (now with capital O-) ‘the eastern regions of the world, eastern countries’ (originally vaguely meaning the region east and south of Europe, what is now called the Middle East but also sometimes Egypt and India), from Old French orient ‘east’ (11th century), from Latin orientem (nominative oriens) ‘the rising sun, the east, part of the sky where the sun rises,’ originally ‘rising’ (adj.), present participle of oriri ‘to rise’.

Same applies to his slipperiness in defining what ‘Orientalism’ means. He gives at least ten distinct definitions (on pages 41, 73, 95, 120, 177, 202, 206, 300 and more) but it’s possible to arrive at the end of the book without have a really crystal clear definition of his ostensibly central concept.

Said is not a historian

This really matters because he is dealing with history, the history of European empires and of the texts which, he claims, though written by supposed ‘scholars’, in practice served to underpin and justify imperial rule. But thousands of historians of empire have passed this way before him and his text , whenever it strays into pure history, feels like history being done by an amateur.

It feels particularly true when he again and again suggests that what underpinned the British and French Empire’s control of their colonial subjects was the academic knowledge grouped under the heading Orientalism – and takes no account of some pretty obvious other factors such as economic, technological or military superiority.

In a sense he can’t afford to for at least two reasons: 1) because if he did get into, say, the economic basis of empire, his account would end up sounding like conventional history, and second-rate economic history at that; 2) literature and scholarly texts are his stomping ground a) because he’s just more familiar with them b) because his central premise is that knowledge is power; conceding that there are other types of power immediately undermine the narrow if intense scope of his book.

Histories of empires

In the introduction Said says that the chief imperial powers in the Middle East and India were a) Britain and France through to the mid-twentieth century, and b) America since.

This feels a bit gappy. John Darwin’s brilliant comparative study of the Eurasian empires, After Tamerlane, teaches us that ’empire’ has been the form of most governments of most civilisations for most of history. Imperialism is the ‘natural’ form of rule. It’s ‘democracy’ which is historically new, problematic and deeply unstable.

Were the British and French empires somehow unique?

No, in two ways. Taking a deep historical view, Darwin shows just how many empires have ruled over the Middle East over the past two and a half thousand years, namely: the Assyrian Empire, the Babylonian Empire, the Parthian Empire, the Persian Empire, the Moghul Empire, the Athenian Empire, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Seljuk Empire, various Muslim caliphates who concentrated on conquering territory the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Ottoman Empire (or Caliphate). So the British Empire’s relatively brief period of control was neither the sole nor the most important influence.

The role of the Ottoman Empire in falling to pieces during the nineteenth century, leading to mismanagement, repression and the rise of nationalist movements across its territories is never given enough credit in these kinds of books. It’s always the French and British’s faults, never the Turks’.

Second, focusing on Britain and France may be justified by the eventual size of their territorial holdings, but downplays the rivalry with and interference of other European imperial powers. For example, Sean McMeekin’s brilliant book ‘The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany’s Bid for World Power, 1898 to 1918‘ shows how the newly united German Reich (or empire) elbowed its way into the Middle East, with its own Orientalising scholars and preconceptions.

And Said completely ignores the Russian Empire. For me this is the most interesting empire of the 19th century because I know nothing about it except that it expanded its control relentlessly across central Asia, as far as the Pacific where it eventually got into a war with Japan (1905). But long before that Russia had ambitions to expand down through the Balkans and retake Constantinople from the Turks, re-establishing it as a new Christian city, the Second Rome. This is one of the most mind-boggling aspects of Orlando Figes’s outstanding book about The Crimean War (1853 to 1856).

Blaming Britain and France just feels like blaming ‘the usual suspects’. Very limited.

Putting politics back into scholarship

He says on numerous occasions that 19th century Orientalist scholars claimed that their work was objective and scholarly and completely unconnected with the way their countries exercised imperial dominion over the countries whose cultures they studied – and that this was of course bullshit. The Orientalist scholars were only able to carry out their studies because they could travel freely across those countries as if they were the members of the imperial ruling caste. Therefore his project is very simple: it is to put the politics back into supposedly neutral, ‘detached’ scholarly analysis.

This struck me as being very Marxist. It was Marx who suggested that cultures reflect the interests of the ruling class, aristocratic art in the 17th and 18th centuries, bourgeois art and literature with the rise of the industrial bourgeoisie in the 19th century – and made the point which underpins Said’s whole position, that supposedly ‘neutral’ bourgeois scholarship always always always justifies and underpins the rule of the bourgeoisie, there’s nothing ‘neutral’ about it.

Christendom versus Islam

Said claims that Western civilisation, that Christendom, largely defined itself by contrast with the Muslim world for 1,000 years from the rise of Islam to the decline of the Ottoman Empire, as if this is a subversive insight. But to anyone who knows European history it’s obvious. Expansionist militarist Islam had already seized half the territory of the former Roman Empire and threatened to invade up through the Balkans and, potentially, exterminate Christendom. You would notice something like that. I’d have thought it was schoolboy-level obvious.

General thoughts

The Other

At regular intervals Said invokes the notion of ‘the Other’ which is always presented in critical books like this as if it was a big bad bogeyman, but I always find the idea a) childish b) too simplistic. If you read Chaucer you’ll see that his notion of ‘the Good’ is defined in hundreds of ways, most of which have nothing to do with Islam. OK when he refers to the Crusades (the Knight’s Tale) he does mention Islam. But there’s lots of other things going on in European texts, lots of ways of creating value and identity, which Said just ignores in order to ram home his point.

It’s an irony that Said says the use of the simple binary of East and West is too simplistic but then uses an even more simplistic term, ‘the Other’, replacing one simplistic binary with another which just sounds more cool.

What if the East really is a threat to the West?

Fear of the Other is always treated in modern humanities, in countless books, plays, documentaries, in artworks and exhibition texts, as if it is always a bad thing, irrational, can only possibly be prompted by racism or sexism or xenophobia or some undefined ‘anxiety’.

But what if things really do get worse the further East you go? What if the governments of Eastern Europe, such as Poland or Hungary, really are worryingly authoritarian and repressive? What if the largest country in the world, which dominates ‘the East’, Russia, has clearly stated that Western liberal democracy is finished, carries out cyber-warfare against infrastructure targets in the West, and has invaded and committed atrocities in a West-friendly neighbour? What if ‘the East’ is a source of real active threat?

As to the Middle East, what if it is subject to one or other type of civil war, insurgency, and horrifying acts of Islamic terrorism, widespread atrocities committed in the name of Allah, and the region’s chronic political instability?

And further East, what if the most populous nation on earth, China, is also known to be carrying out cyber attacks against Western targets, operates spy networks in the West, and is raising tensions in the Pacific with talk of an armed invasion of Taiwan which could escalate into a wider war?

Isn’t it a simple recognition of the facts on the ground to be pretty alarmed if not actually scared of many of these developments? I don’t think being worried about Russian aggression makes me racist. I don’t think being appalled by barbaric acts in the Middle East (ISIS beheading hostages, Assad barrel-bombing his own populations) means I’m falling prey to Orientalist stereotypes.

I don’t think I’m ‘Othering’ anybody, not least because there are lots of players in these situations, lots of nations, lots of governments, lots of militias and ethnic and religious groups, so many that simply summarising them as ‘the Other’ is worse than useless. Each conflict needs to be examined carefully and forensically, doing which generally shows you the extreme complexity of their social, political, economic, religious and ethnic origins.

Just repeating the mantras ‘Oriental stereotyping’ and ‘fear of the Other’ strikes me as worse than useless.

Britain and the East

Said goes on at very great length indeed about the British Empire and its patronising stereotyped attitudes to ‘the East’, ‘the Orient’ and so on.

But, because he’s not a historian, he fails to set this entire worldview within the larger perspectives of European and British history. Attacks and threats have always come from the East.

The ancient Greeks and Romans feared the East because that’s where the large conquering empires came from: the Persian Empire which repeatedly tried to crush the Greek city states and the Parthian Empire’s threat to the Romans went on for centuries. When Rome was overthrown it was by nomadic warrior bands from ‘the East’.

As to Islam, all of Europe was threatened by its dynamic expansion from the 7th century onwards, which conquered Christian Byzantium and pushed steadily north-west as far as modern Austria, while in the south Muslim armies swept away Christian Roman rule across the whole of North Africa, stormed up through Spain and conquered the southern half of France. They were only prevented from conquering all of France – which might have signalled the decisive overthrow of Christian culture in Europe – had they not been halted and defeated at the Battle of Tours in 732.

As to Britain, we were, of course, invaded again and again for over a thousand years. Britain was invaded and conquered by the Romans, invaded and conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, invaded and conquered by the Vikings, then invaded and conquered by the Normans.

Attacks on Europe always come from the East and attacks on Britain always come from the East. Napoleon threatened to invade in the early 1800s and in the later part of the nineteenth century many Britons lived in paranoid fear of another French invasion. Hitler threatened to invade and obliterate British culture in the name of a horrifying fascism.

So the fundamental basis of these views isn’t some kind of persistent racism, isn’t fancy ideas about ‘the Other’ or ‘imperial anxiety’, it’s a basic fact of geography. Look at a map. Where else are attacks on Europe, and especially Britain, going to come from? The Atlantic? No, from the East.

Throughout European history the East has been synonymous with ‘threat’ because that’s where the threat has actually come from, again and again and again. For me, these are the kinds of fundamental geographical and historical facts which Said simply ignores, in order to sustain his thesis.

And what if the Orient actually was alien, weak, corrupt and lazy?

Said repeats over and over again that Western, Orientalising views of the Middle East or Islam loaded it with negative qualities – laziness, inefficiency, corruption, violence, sensuality – in order to help us define and promote our own wonderful values, of hard work, efficiency, honesty in public life, good citizenship, Protestant self restraint and so on.

You can see what he’s on about and I accept a lot of what he says about Western stereotyping, but still… what if the West was, well, right. This is where a bit of history would come in handy because even modern, woke, post-Said accounts of, say, the declining Ottoman Empire do, in fact, depict it as corrupt, racked with palace intrigue, home to astonishing brutality from the highest level (where rival brothers to the ruling Sultan were liable to be garrotted or beheaded) to public policy.

I’ve just been reading, in Andrew Roberts’s biography of Lord Salisbury, about the Bulgarian Atrocities of 1876 when an uprising of Bulgarian nationalists prompted the Ottoman Sultan to send in irregular militias who proceeded to rape, torture and murder every Bulgarian they came across, with complete impunity. Up to 30,000 civilians were slaughtered, prompting the British government to abandon its former stalwart support for the Ottomans. My point is this wasn’t invented by Orientalists to justify their racist stereotypes about the violent barbaric East; nobody denies that it happened, it was widely publicised at the time, and it moulded a lot of people’s opinions about Ottoman rule based on facts.

Anybody who tried to do business or diplomacy with the Ottoman Empire quickly came to learn how corrupt and venal it was. So what happens to Said’s thesis that all these views were foundationless stereotypes, artificial creations of the racist Western imagination – if historical accounts show that inhabitants of the Orient, which he defines at the Middle East, really were lazy, inefficient, corrupt, violent.

For example, in his book about the railway line which the Kaiser wanted to build to Baghdad, Sean McMeekin describes the comic meeting between German engineers and Turkish labourers. No ‘Orientalism’ was required for the contrast between Teutonic discipline and efficiency and the corrupt, lazy ineffectiveness of the Turks to be clear to all involved.

Said’s style

Said is long-winded and baggy. He never uses one word or concept where fifteen can be crammed in. Moreover, he is clearly aspiring to write in the high-falutin’ style of the Parisian intellectuals of the day, Roland Barthes or Michel Foucault, who used recherché terms and tried to crystallise new ideas by emphasising particular terms, words used in new, lateral ways, teasing out new insights. At least he hopes so. Here’s a slice of Said, made up of just two sentences.

Orientalism is not a mere political subject matter or field that is passively reflected by culture, scholarship, or institutions; nor is it a large and diffuse collection of texts about the Orient; nor is it representative and expressive of some nefarious ‘Western’ imperialist plot to hold down the ‘Oriental’ world. It is, rather, a distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly, economic, sociological, historical, and philological texts; it is an elaboration not only of a basic geographical distinction (the world is made up of two unequal halves, Orient and Occident) but also of a whole series of ‘interests’ which, by such means as scholarly discovery, philological reconstruction, psychological analysis, landscape and sociological description, it not only creates but also maintains; it is, rather than expresses, a certain will or intention to understand, in some cases to control, manipulate, even to incorporate, what is a manifestly different (or alternative and novel) world; it is, above all, a discourse that is by no means in direct, corresponding relationship with political power in the raw, but rather is produced and exists in an uneven exchange with various kinds of power, shaped to a degree by the exchange with power political (as with a colonial or imperial establishment), power intellectual (as with reigning sciences like comparative linguistics or anatomy, or any of the modern policy sciences), power cultural (as with orthodoxies and canons of taste, texts, values), power moral (as with ideas about what ‘we’ do and what ‘they’ cannot do or understand as ‘we’ do). (p.12)

That second sentence is quite exhaustingly long, isn’t it? In my experience, you often get to the end of Said’s huge unravelling sentences with the impression that you’ve just read something very clever and very important, but you can’t quite remember what it was.

A key element of his style, or his way of thinking, is the deployment of lists. He loves long, long lists of all the specialisms and areas which he claims his ideas are impacting or pulling in or subjecting to fierce analysis (power political, power intellectual, power cultural, power moral and so on).

On the one hand, he is trying to convey through monster lists like this, a sense of the hegemony of Orientalist tropes i.e. the way they – in his opinion – infuse the entire world of intellectual discourse, at every level, and across every specialism. This aim requires roping in every academic discipline he can think of.

On the other hand, his continual complexifying of the subject through list-heavy, extended sentences, through the name-dropping of portentous critical theorists, threatens to drown his relatively straightforward ideas in concrete.

Said describes the process of close textual analysis very persuasively but, ironically, doesn’t actually practice it very much – he is much happier to proceed by means of lists of Great Writers and Orientalist Scholars, than he is to stop and analyse any one of their works.

He explains that it would be ‘foolish to attempt an encyclopedic narrative history of Orientalism’ but this is deeply disappointing. That might have been really solid and enduring project. Instead we are given a surprisingly random, digressive and rambling account.

His actual selection of example, of texts which he studies in a bit of detail, is disappointingly thin. This explains why you can grind your way through to the end of this densely written 350-page book and not actually have a much clearer sense of the history and development of the academic field of Orientalism.

And lastly, he just often sounds unbearably pompous:

And yet, one must repeatedly ask oneself whether what matters in Orientalism is the general group of ideas overriding the mass of material? (p.8)

One uses the phrase ‘self conscious’ with some emphasis here because… (p.159)

And his frequent straining for Parisian-style intellectual rarefication sometimes makes him sound grand and empty.

I mean to say that in discussions of the Orient, the Orient is all absence, whereas one feels the Orientalist and what he says as presence; yet we must not forget that the Orientalist’s presence is enabled by the Orient’s effective absence. (p.208)

No, no we must never forget that. Forgetting that would be dreadful.

Lastly, he cites quotations, sometimes quite long quotations, in French without bothering to translate them. This is impolite to readers. On a smaller scale he drops into his prose Latin or French tags with the lofty air of an acolyte of Erich Auerbach’s grand traditions of humanist criticism who expects everyone else to be fluent in French and German, Latin and Greek.

Nevertheless, [in French Orientalist Louis Massigon’s view] the Oriental, en soi, was incapable of appreciating or understanding himself. (p.271)

It would be more polite, and effective, to take the trouble to find adequate English equivalents.

Immigration

When the book was published, in 1978, there weren’t many immigrants of any colour in Britain and Said could confidently talk about scholars and an academic world, as well as the nation at large, which was largely white. In other words ‘Orientals’ were still rare and relatively unknown.

In the 45 years since the book was published, mass immigration has changed the nature of all Western countries which now include not only large communities of black and Asian people, but eminent black and Asian cultural, political and economic figures. As I write we have a Prime Minister, Home Secretary and mayor of London who are all of Asian heritage.

I dare say fans of Said and students of post-colonial studies would point out the endurance of ‘latent’ Orientalism i.e. the continuation of prejudice and bigotry against the Arab and Muslim and Indian worlds, especially since the efflorescence of vulgar imperialist nostalgia around the Brexit debate.

Nevertheless, I imagine the unprecedented numbers of what used to be called ‘Orientals’ who now routinely take part in Western political and cultural discourse, who write novels and plays, direct films, comment in newspapers and magazines, host TV shows and, of course, teach courses of postcolonial and subaltern studies, would require Orientalism to be comprehensively rethought and brought up to date.

The modern Middle East

At the end of the day, Orientalism is a largely ‘academic’ book in two senses:

1. On reading lists for students

Said primarily set out to change attitudes within universities and the humanities. In this he was dramatically successful, and it is impossible to read about the European empires and, especially, to read about 19th century imperial art, without his name being invoked to indicate the modern woke worldview, the view that almost all European arts and crafts which referenced ‘the Orient’ are morally, politically and culturally compromised or, as he bluntly puts it on page 204, racist, imperialist and ethnocentric.

Said provides some of the concepts and keywords which allow modern students of the humanities to work up a real loathing of Western civilisation. Good. The Russians want to abolish it, too.

Irrelevant for everyone else

But it’s also ‘academic’ in the negative sense of ‘not of practical relevance; of only theoretical interest’. What percentage of the public know or care about the opinions of nineteenth century Orientalist scholars? For all practical purposes, nobody. Who gets their ideas about the modern Middle East from the poetry of Gérard de Nerval, the letters of French novelist Gustave Flaubert or umpteen Orientalising Victorian paintings? Nobody.

I suggest that most people’s opinions about the Middle East derive not from poetry or paintings but from the news, and if they’ve been watching or reading the news for the last 20 years, this will have involved an enormous number of stories about 9/11, Islamic terrorism, Islamic terror attacks in London and Manchester and other European cities, about the 2001 US overthrow of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the 2003 coalition invasion of Iraq, the long troubled military struggles in both countries, the 2011 Arab Spring followed swiftly by civil war in Libya, the terrible civil war in Syria, the military coup in Egypt, the ongoing civil war in Yemen, and just recently the humiliating and disastrous US withdrawal from Kabul (2021).

Remember the heyday of Islamic State, the videos they shot of them beheading Western hostages with blunt knives? Footage of them pushing suspected gays off rooftops? Blowing up priceless ancient monuments?

Alongside, of course, the perma-crisis in Israel with its never-ending Palestinian intifadas and ‘rockets from the Gaza Strip’ and retaliatory raids by the Israeli Defence Force and the murder of Israeli settlers and the massacres of Palestinians, and so on and so on.

And you shouldn’t underestimate the number of Westerners who personally know people who fought in one or other of those wars; for example, 150,610 UK personnel served in Afghanistan and some 141,000 in Iraq. All those soldiers had family, who heard about their experiences and shared their (sometimes appalling) injuries and traumas. First hand testimony trumping Victorian paintings.

And quite a few Westerners have been affected by one or other of the many Islamic terrorist attacks on Western cities, starting with the 2,996 killed in the 9/11 attacks and all their extended families, the 130 people killed in the 2015 Bataclan attack in Paris, the families of the 22 people killed and 1,017 injured in the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing; or attacks on tourists in Muslim countries such as the 202 killed and 209 injured in the 2002 Bali bombings, numerous Islamist attacks in Egypt, Tunisia and other tourist favourites.

Compared to the images and news footage and reports and first hand experience of these kinds of events, I’m just suggesting that Said’s warning about the frightful stereotyping of the Orient carried out by nineteenth century and early twentieth century writers, artists and scholars is a nice piece of academic analysis but of questionable relevance to the views about Arabs, Muslims and the Middle East currently held by more or less everyone living in the contemporary world.

Said addresses this point by saying that there is a direct link between older imperial views and current views, that his entire project was not only to show the origins and development of Orientalist views but how they continue up to the present day to inform contemporary news and TV and magazine and political discourse about Islam and the Middle East.

But proving that would require a completely different kind of book, something from the field of media studies which examined how the tropes and stereotypes Said complains are utterly without foundation in the real world, have gained renewed life from actual events which people not only consume via TV and newspapers, but via social media, massacres filmed live, as they happen.

In the 1995 Afterword and 2003 Preface which he added to the book (and I review separately) he does indeed try to do this, but he died (in 2003) well before the advent of social media and cheap phones transformed the entire concepts of media, news and information out of recognition.

In almost all ways, this book feels as if it comes from a bookish, scholarly, library-based world which has been swept away by the digital age.

An interview with Edward Said (1998)

This interview was produced in 1998, so before 9/11, the Afghan War, the Iraq War, al-Qaeda, ISIS, the Arab Spring etc. If Said thought Western attitudes to Middle Eastern countries were bad then, what must he have made of the hugely negative shift in impressions caused by 9/11 and the subsequent wars (he passed away in September 2003, living just long enough to see the American invasion of Iraq, commenced in March 2003, start to unravel)? You could almost say that the interview hails from a more innocent age.

Practical criticism

See if you can identify the kind of essentialising Orientalist stereotypes about the Middle East, Arabs and Islam which Said describes in the coverage of the recent Hamas attack on Israel (I’m just giving the BBC as a starting point):

Credit

Orientalism by Edward Said was first published by Routledge and Kegan Paul in 1978. References are to the 2003 Penguin paperback edition (with new Afterword and Preface).

Related reviews

- Orientalism by Edward Said (1978) part 2

- Orientalism by Edward Said (1978) Afterword and Preface

- After Tamerlane by John Darwin (2007)

- Salisbury: Victorian Titan by Andrew Roberts (1999)

- The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany’s Bid for World Power, 1898 to 1918 by Sean McMeekinlin (2010)

- The Crimean War by Orlando Figes (2010)

- Imperialism reviews