‘What’s it like, being strangled I mean?’ Amanda asked, interestedly.

‘Horrid, really,’ said Virginia.

(Reservation Deferred, page 167)

Published in 1954, this volume collects 15 of Wyndham’s short stories, from the late 1940s through to the publication date. They are entertaining, distracting, clever and superficial, most of them barely even science fiction, more tales of the macabre, straying into Roald Dahl territory, none of them having the imaginative force of his great novels.

- Jizzle (1949)

- Technical Slip (1949)

- A Present from Brunswick (1951)

- Chinese Puzzle (1953)

- Esmeralda (1954)

- How Do I Do? (1953)

- Una

- Affair of the Heart (1954)

- Confidence Trick (1953)

- The Wheel (1952)

- Look Natural, Please! (1954)

- Perforce to Dream (1954)

- Reservation Deferred (1953)

- Heaven Scent (1954)

- More Spinned Against (1953

Jizzle (1949)

Ted Torby works in a circus. He makes a living flogging Dr Steven’s Psychological Stimulator, half a crown buys you a bottle of Omnipotent Famous World-Unique Mental Tonic. His girlfriend is Rosie. On night, drunk, down the Gate and Goat, Ted is talked into buying a performing monkey off a nautical Negro, who he knocks down in price to ten pounds and a bottle of whiskey. Monkey is named Giselle, which drunk Ted pronounces as Jizzle.

Jizzle’s skill is being able to draw astonishingly life-like portraits of people. Next stop of the circus Ted unveils a new act, amazing performing Giselle. Gets members of the audience to come up and have their portraits drawn. Everyone thinks it’s a joke till the monkey actually does it, then they all clamour to have their portrait done and pay handsomely.

Ted keeps Jizzle in his caravan where she irritates him with her constant snicker sound. Rosie resents and threatens Jizzle. One day Ted stumbles back to the caravan drunk and furious, Jizzle has drawn an anatomically explicit picture of Rosie having it off with the circus strongman. She protests her innocence but Ted slaps her about a bit and throws her out. Jizzle sits up on the wardrobe snickering her snicker. Next day she and the circus strong man have gone.

But Ted misses Rosie. Weeks pass and he gets fed up of Jizzle. Eventually sells her on to George Haythorpe of the Rifle Range act. George leaves that act in the hands of his wife, Muriel, then takes over Jizzle’s drawing act, while George takes a commission. Reluctantly Jizzle is moved to George’s caravan. But Ted is still lonely.

One night there’s a loud banging on his caravan door which is thrown open to reveal a furious George with Jizzle on his shoulder. Furious, George holds out a drawing obviously by Jizzle, a no-hold-barred, explicit drawing of Ted having sex with George’s wife, Muriel. Even as Ted stammers to deny it, to say it’s just not true, even as it dawns on him that Jizzle drew it out of malice just as he drew the incriminating sketch of Rosie and the weightlifter, as realisation dawns and he blusters and stammers he sees George raise his rifle and the last thing Ted Torby hears is… the sound of Jizzle, snickering.

Technical Slip (1949)

On his deathbed Robert Finnerson is approached by a strange shabby official named Prendergast, who offers him the chance to live his whole life over again. If he signs a contract assigning his soul to the devil. Still, Finnerson agrees, finds himself wandering through the Edwardian square where he lived as a boy, hiding behind the bushes, being found and… he is that boy, that small boy in an Edwardian sailor suit in circa 1910. And for the next few days he has the surreal experience of having the mind, the adult mind of a man who has lived this life once already, but in the body of a boy, and surrounded by sister, father, mother and nursemaid none of whom know anything about the future.

And because he knows about time, about the sequence of events, he is, in the classic manner of all time travellers, able to change them. Hence, one afternoon as they are being taken across the road to play in the square, he suddenly realises he is in the moment of time when a ‘high-wheeled butcher’s trap’ runs amok and crushes his sister’s foot, thus consigning her to a lifetime of misery. As he hears the first sounds of the panic-stricken horse as the cart hoves into view, and realises everything that will follow this tragic moment, he pulls his sister back across the road, and down the steps into the house’s area, and inside the scullery door so that she is safe. The accident never happens. His sister’s life will be utterly different.

Now, the opening words of the story had been a parody of a busy bureaucrat telling a functionary to go and deal with Contract XB2823, the point being we are eavesdropping on a satirical parody of how hell and its minions are supposed to function. And so the story ends the same way: clearly the transporting of Finnerson back into his boy’s body should not have taken his mature, adult mind. That is the technical slip referred to in the title. Tut tut.

And so it is now, towards the end of the story, that we overhear the same bored administrator’s voice reprimanding Prendergast and telling him there’s been a slip-up. He needs to go see the chaps in Psychiatry and tell them to wipe Finnerson’s mind clean. And thus it is that the final little passage of this story describes the next morning when Finnerson wakes up in bed, yawns and thinks and behaves like an ordinary 10-year-old boy. His mind-wipe has been successful.

And yet… For the rest of his life Robert Finnerson is haunted by a strange sense that he has been here before, seen it, heard it, experienced things before, strange ‘flashes of familiarity’ ‘as if life were a little less straightforward and obvious than it seemed…’ (p.29)

A Present from Brunswick (1951)

Set in small town America, an American mom, Mrs Claybert, is a member of a local women’s recorder club. One day she receives from her son, Jem, serving in the US Army in Europe, an ancient and beautifully decorated recorder-cum-pipe. When she tries it out at the next meeting of her music group, all the members stop their instruments and find themselves rising to their feet and following her dancing down the street, until… a traffic cop stops them and breaks the spell.

There follow a few pages of reflection, Mrs Claybert at home with the pipe, fingering it wistfully, reflecting that she quite likes her husband but really misses her son, Jem, children more generally. Is the pipe, as one of the moms joked, actually the ancient carved wooden pipe of the Pied Piper of Hamlyn?

Mrs C takes a bus out of town to the countryside, walks to an isolated copse, sits by a tree and tentatively lifts the pipe to her lips. Cut to main street of her hometown (Pleasantgrove) and what has happened is that her playing in the woods has woken or brought thousands of children to follow her, children dressed in medieval garb who she has brought following her dancing back into the heart of her American town. Now they’ve brought the traffic to a standstill and are clogging up the centre of town. The crisis forces the mayor to come down and engage in an angry conversation with Mrs C about what they’re going to do with all these orphan children?

Disgusted by their philistine, unsympathetic attitude, Mrs C lifts the pipe to her lips and dances out of town followed not only by the Hamlyn children, but by the children of the townsfolk, too.

It is a classic example of Wyndham’s simple approach, to start with a simple premise – What would happen if someone found the actual pipe used by the pied piper of Hamlyn – and then applied to the humdrum, everyday world we actually live in with its traffic and unsympathetic cops and harassed politicians.

Chinese Puzzle (1953)

Hwyl and Bronwen Hughes live in South Wales. One day they receive a package from their son, Dai, serving in the navy in the sea off China. It’s packed with sawdust and contains one large shiny egg. It hatches and proves to be a dragon, breathes fire and everything. They keep it indoors till it sneezes and burns the carpet, then Hwyl builds a hutch outside in their yard.

The Hughes’s come into rivalry with Idris Bowen, left winger, rabble rouser, who mounts several attacks on the dragon, rampaging in the Hughes’s backyard, trying to steal it, then accusing it of breaking into his henhouse and killing all his chickens.

You’d have thought the idea of a real live dragon would lead to romantic and/or apocalyptic conclusions but, as with the tube train to hell (below), the fantastic is smoothly incorporated into the everyday and mundane. Thus nobody seems very surprised to discover they have a real fire-breathing dragon in their midst, what does get Bowen going, makes him angrily address branch meetings of his trade union and so on, is that the dragon is a Chinese imperial dragon i.e. a tool of the capitalist class and mine owners.

So the really bizarre thing about the story isn’t the dragon, as such, it’s that it prompts highly politicised argument among different sections of the South Wales working class. After a series of confrontations and arguments, Idris Bowen excels himself by ordering and taking delivery of a traditional Welsh dragon! A good working class dragon, and he organises a full-on, staged dragon fight in some waste land along by the coal mine slag heaps.

As if this wasn’t all bizarre and entertaining enough, there’s a twist in the tail, which is that the two dragons, after being released from their cages among a crowd of shouting men, cautiously circle each other and then…. instead of fighting to the death, fly off into the nearby mountains.

As so often it is given to the female character, to Bronwen Hughes, to point out the obvious thing which the squabbling men had completely overlooked: the dragons are male and female (their Chinese dragon female, the red Welsh dragon male) and so they have flown off into the mountains to do what comes naturally. Soon there will be broods of baby dragons. Love trumps politics (especially the divisive, class-based politics of loudmouth Idris Bowen, which Wyndham so disliked).

Arguably the most striking thing about this story isn’t the story at all, it is Wyndham’s powerful evocation of the strong Welsh accent and peculiar speech patterns of the south Welsh.

Esmeralda (1954)

The narrator, Joey, makes a living by running a flea circus. He describes in some detail a prize-winning performing flea he recently bought and names Esmeralda. But the flea circus element is overshadowed by Joey’s love triangle, attracted as he is to both 19-year-old Molly Doherty and trapeze artist Helga Liefsen. There’s lots of detail about what a flea circus looks like and how you train the fleas, how Joey conceives performances and organises the fleas to mimic being a jazz band and so on.

But this is somewhat uneasily superimposed on the love triangle and reaches a little climax when Joey wakes up one morning to find a dozen or so of his star fleas, including Esmaralda, have gone missing, presumed kidnapped. That evening he goes on a date with sexy Helga, walking and talking through the fields where the circus is encamped. When they arrive back at her caravan, Joey begs to come in ‘for a night-cap’ as young men the world over.

Only for them both to leap up from under the bed covers when they realise they are being bitten, by fleas, yes by Joey’s kidnapped fleas. Jealous Molly must have kidnapped them and strewn them in Helga’s bed. Furious with him and his verminous profession, she throws him out and lands a trapeze artist’s punch in the head for good measure.

But Joey’s troubles aren’t over. Next morning Molly’s dad knocks on his caravan door. He’s mighty miffed, wants to know where Joey was last night, why he was out so late. Why? He stretches out his cupped hand and opens it to reveal Esmaralda! Where did he find her? Molly’s mother found her in Molly’s bed. ‘And just what do you propose to do about that, son?’ says old man Doherty in a threatening tone.

Long story short, Joey is forced into a shotgun marriage to Molly. And a year later, on their first wedding anniversary, she gives him a present: a tie pin made of fourteen carat gold, with a little oval of glass at the top and, embedded in the glass, the preserved body of Esmaralda, the prize-winning flea which brought them together. With a little help from clever Molly.

As in the dragon story, one of the strong elements in this tale is the way Wyndham sets out to capture a strong accent, in this case American working class speech rhythms.

How Do I Do? (1953)

A woman goes to see fortune teller, but makes her so angry with her scepticism the gypsy woman scoops her up and into the crystal ball where she suddenly finds herself in the future. She doesn’t immediately realise it, thinking she’s simply left the fortune teller’s and decides to go for a walk to the old house she fancies buying one day, only to discover it has been radically restored and painted and improved and is stunned when the little girl playing with her dollies on the front lawn shouts ‘Mummy mummy’ and comes to hug her. Even more so when a handsome man emerges from the house, kisses her and pats her bottom before jumping into his car and motoring off to meet a friend.

The final straw comes when a woman emerges from the house and it is her future self, who calmly greets her and says, ‘Yes, I’ve been wondering when you’d turn up’ because, of course, in the future this has all happened already.

Una

The narrator works for the Society for the Suppression of the Maltreatment of Animals, along with colleague Alfred Weston. A deputation from the village of Membury invite them to investigate strange goings-on up at the Old Grange. They’re prompted to do so by the advent in their high street of two five foot six creatures which look like turtles with horny carapaces front and back but human-type heads peeking out the top and human arms out the sides. When the villagers made as if to threaten them the creatures waddled off over country blundering into Baker’s Marsh where they sank without trace.

At first I thought these were aliens but then it turns into a comic version of The Island of Dr Moreau. The narrator and his colleague Alfred Weston go up to Membury Grange where they are greeted by Dr Dixon who has, of course, been carrying out experiments on animals and humans, literally piecing them together from dead body parts.

In fact it turns out Dr Dixon was once a biology teacher at the narrator’s school who reputedly inherited millions of pounds, packed in teaching to set up his own lab (p.95). Now he shows them around his lab and, finally, to the cage of his pièce de resistance, his Perfect Creature, whom he has named Una. She is a monstrosity:

Picture if you can, a dark, conical carapace of some slightly glossy material. The rounded-off peak of the cone stood well over six feet from the ground: the base was four foot six or more in diameter; and the whole thing supported on three short, cylindrical legs. There were four arms, parodies of human arms, projecting from joints about half-way up. Eyes, set some six inches below the apex, were regarding us steadily from beneath horny lids. For a moment I felt close to hysterics. (p.102)

Una decides she wants to mate with Weston and becomes so distraught she swipes for him through the bars and then demolishes the bars and breaks free, moving with the obliterating force of a tank as the three men run for cover. First she demolishes the laboratory wing, then bursts through the barred door and into the main house. As our three heroes bolt up the stairs Una barges into the stairs and demolishes them. Comically, Weston falls into her four arms and she starts to croon besottedly to him.

Firemen and ambulance and police arrive and try to corral Una, while trying to loop Weston in a rope and hoist him free. Nothing doing. Una spots the rope, breaks free of it, bursts through the front door and lumbers off down the drive, towing the rope and half a dozen firemen still clinging on to it behind her. Their colleagues start the fire engine and give chase as Una breaks through the wrought iron gates to the Grange, still cradling Weston in her arms and crooning to him, onwards she goes, turning off the main road and into a steep side lane heading down to the river.

But this is her undoing. Trucking across an ancient packhorse bridge her weight makes the central span collapse into the river and, of course, Una has no ability to swim like any kind of earthly creature, so sinks like a rock. The firemen rescue Weston and pump the water out of him.

The story concludes with the boom-boom punchline that Alfred Weston has now changed profession from being an animal cruelty inspector, since he finds it impossible to look a female animal of any kind in the eye without a shiver of horror!

The Island of Dr Moreau played for laughs.

Affair of the Heart (1954)

Elliot and Jean are just settling down at their restaurant table when Jules the waiter hurries up to tell them there’s been a mistake and please could they move. This table is always reserved, every 28 May, for a particular couple, Mrs Blayne and Lord Solby. This couple duly arrive and Elliot and Jean, piqued at being moved, observe them closely. Jules the waiter tells them it is a Great Unrequited Love Affair, that Mrs Blayne was once young Lily Morveen, the Talk of the Town, pursued by countless eligible bachelors, in particular Charles Blayne and Lord Solby. She married Blayne but then the Great War broke out and both men went to serve and Charles was, tragically, killed.

Anyway the crux of the story is that Jules, other patrons, and through them, Jean and other diners, all accept that it is a heroic love story, that Lord Solby has always carried a torch for Mrs Blayne, that this annual meeting is where he pluckily renews his suit and she stoically spurns him because she is staying true to the memory of her late husband.

Except that Elliott happens to be a phonetician by trade, and is expert in lip reading. Thus it is he, alone of all the diners and staff, who can actually lip read what the couple are saying to each other and realises that – she is blackmailing Solby! For she knows what really happened in that trench on the Western Front (I think the implication is that Solby murdered or arranged for Blayne to be killed) and this annual remembrance dinner has nothing soppy or sentimental about it. It is the annual business meeting in which she confirms her determination to squeeze Solby till the pips squeak.

Confidence Trick (1953)

The main character, Henry Baider, takes a tube on the Central Line heading west from Bank. It is absolutely jam packed as usual, barely room to breathe. Somewhere after Chancery Lane the train comes to a sudden halt and the lights go off. When it starts up again the man is thrown sideways and surprised to find almost everyone has disappeared. When the lights come fully on he is amazed to see there are only five people in the carriage. Hang on. Where, when did all the others go?

The five passengers reluctantly draw together as the journey stretches on and on. Norma Palmer is shopgirl class. Robert Forkett is a conventional City gent. Mrs Barbara Branton considers herself a cut above the rest. And a man asleep at the end of the carriage. Henry notices the strap hangars are hanging at an angle. They are heading steadily downhill.

Eventually, after an hour and a half they pull into a station. One of the passengers thinks it’s ‘Avenue’ something but our protagonist realises it is Avernus, Latin term for Hell. And sure enough, the train pulls up in hell. Only it is a very English, comedic hell. It is demons with pointy tails who shout ‘All change’ and force passengers out the carriages. (At this point they wake up the sleeping man, a strong looking young man we learn is named Christopher Watts, physicist.)

Up the escalator they go to discover down-on-their-luck devils hawking dodgy goods from a tray like war veterans, products like an anti-burn lotion or first aid kit. It’s true they see a naked woman hanging upside down from her ankles but even these atrocity moments are played for laughs as hoity-toity Mrs Branton twists her face to be sure that she recognises an old acquaintance. Well, who’d have thought!

It’s an odd mixture of sort of sci-fi earnestness, with a mix of Hetty Wainthrop Investigates, down-to-earth humour. Thus burly Christopher Watts, refusing to be bossed around, grabs the first demon to poke him by his tail and swings round and round and flings him far into some kind of barbed wire compound as from a concentration camp.

The other demons react by approaching and circling round him when Christopher has a mental breakthrough. Suddenly he straightens up and like Graham Chapman in a Monty Python sketch, declares: ‘Dear me, what nonsense this all is!’ and, in a flash, Henry realises he’s right. The whole thing is absurd. He starts to smile. Watt squares up and says ‘I don’t believe it’ and then, in a much louder voice, ‘I DON’T BELIEVE IT.’ and somehow not believing it is all it requires. For the flaming mountains and the lake of fire and the burning cliffs and the entire landscape of hell begins to crumble and collapse as in a John Martin painting.

Until suddenly it is pitch black and they can only dimly see the lights from the tube train which is still there somehow. The five mortals make their way back to it and clamber aboard. The doors close. It begins to trundle along the line, slowly ascending, as the five, in their different ways, try to process what has just happened to them.

To everyone’s surprise conservative City man Mr Forkett expresses disapproval. For him there are traditions and rules and forms which must be obeyed. This escalates into an argument with Watt, who presents himself as a man of reason and experiment and scepticism. Forkett ends up calling him a Bolshevist and a dangerous radical.

It’s a long journey and one by one they fall asleep. When they wake… the train is packed again, jam packed with rush hour commuters, it is running along the actual Central Line. Over someone’s shoulder Henry glimpses headlines of the evening paper: ‘RUSH HOUR TUBE SMASH: 12 DEAD’ and gives a list of the dead and their names are among them.

Ah. Aha. So. So they died (along with seven others in other carriages), that’s why the train was suddenly empty, it was a ghost train taking them to hell. Somehow Christopher Watt’s huge act of disbelief has overthrown the order of things and liberated them from hell. Mrs Branton says she doesn’t know what her husband will say. Exactly, says Mr Forkett looking at Henry. Overturning the established way of doing things, there’ll be paperwork, post mortems, coroners reports and all sort of procedures thrown into chaos by this unfortunate young man. Which is itself a facetious and satirical way of thinking about being rescued from death and hell…

This leads to the unexpected denouement. You’d have thought a tube journey to hell was quite enough of a subject for one short story, but when the five passengers re-emerge above ground at Bank station Henry and Forkett watch as Christopher Watt makes his way purposefully over to the Bank of England. Is he going to… to use his new-found power to… to overthrow the Bank of England and the entire reality it exists in?

Yes. For Watt positions himself in front of the bank and starts to say what he said in hell. The ground shakes a little. A statue falls off the facade. Then he gears up for the big booming declaration which brought down hell, ‘I’, he begins as the building starts to tremble and shake, ‘DON’T’, but he hasn’t got as far as ‘BE–’ before a sharp shove from Forkett pushes Watt in front of a bus which crushes him. The ground stops shaking. The Bank stops wobbling. Reality has been saved. As the police close in on Mr Forkett, he has time to observe that he’ll probably be hanged and you know what – he approves. After all, ‘tradition must be observed.’ (p.135)

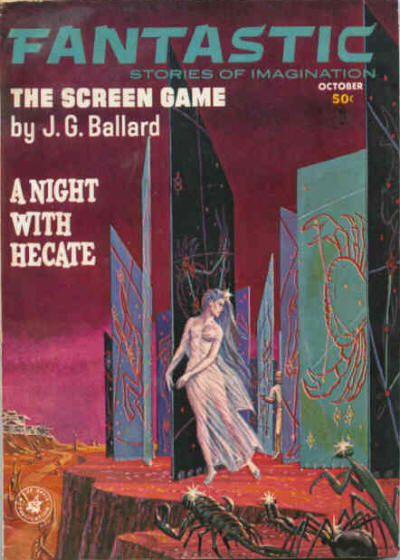

So the story contains two distinct elements: one is the tube journey to hell, which is what people remember and is mentioned on the blurb on the back of the book and forms the subject of the cover illustration. But the second, and just as powerful idea, is about a man who appears to be able to wreck ‘reality’ by the simple assertion that he doesn’t believe in it. In its way this is the more enduring impression of the text, it has a very H.G. Wells feel, it reminds me of Wells’s story The Man Who Could Work Miracles, and makes me wonder what just this part of the narrative would have been like as a stand-alone story.

The Wheel (1952)

This is a dry-run for The Chrysalids and, as such, probably the most powerful story in the collection.

A young boy named David is playing at his rural homestead when he drags into the courtyard some kind of wheeled vehicle, a box on four wooden wheels. Anyway, everyone goes mad, women screaming, young men shouting. The boy is grabbed by adults, by his mother who says she is a god-fearing woman and won’t have evil in her home and thrown into the shed and locked in.

After a while the old man of the community slips into the shed and tries to explain to David what he did so wrong. Remember his prayers? How they ask God to protect them from ‘the Wheel’? Well, those things on the box were wheels and all we know is that back in the Olden Times, the Devil showed man how to make and use wheels, and soon he made bigger and bigger machines that could go faster and faster, rip up the earth, fly through the sky and then…. then IT happened, something terrible, something worse than the Flood, something that obliterated the old world and all its wheeled machines and gave rise to the simpler, plainer world they live in now. A world without wheels. And a world in which religion is focused around making sure wheels never happen again.

What will happen? Well, the community will call the priest and he will burn the wheeled object as unholy and unclean and then, sometimes, they burn whoever made the unclean thing. David is snivelling with fear. On the last page the old man says not to worry. Then he confides that he himself is not afraid of the Wheel. He thinks inventions are neither good or bad but depend on how people use them. He himself was hoping someone would stumble on the wheel, reinvent it, and this time use it for good. He reassures David everything will be OK.

Which explains why, the next day, when the priest arrives to exorcise the wheel, the old man is deliberately working on it and defies the priest and praises the wheels he has built. At which point the crowd seize him in anger and horror. The wheeled thing is burned and the old man is taken away, the implication being he’s taken off to be burned himself.

Leaving young David overlooked and unpunished. Exonerated by the old man’s deliberate sacrifice. But he remembers the old man’s words. It’s only fear that makes things bad. There is nothing bad in wheels, as such. And he vows to remember his grandfather’s words and live life unafraid – the general implication being that he will reinvent the Wheel and this time it will be accepted.

So, like The Chrysalids, it is set in a post-nuclear apocalypse world, a simple rural world whose inhabitants are morbidly terrified of the mindsets of the ‘Old People’ who sparked the apocalypse, and whose religion strictly polices it to prevent a return to the bad old days. And it concerns a young boy named David (the name of the young protagonist of The Chrysalids), who benefits from the kindly attention of an older man (as David does in The Chrysalids) who both explains the origins of the strange worldview they live in, and opens the boy’s eyes to possibility that it may be wrong. Although it invokes a fairly familiar SF trope, this short narrative does so with a power and frisson lacking in most of the other stories.

Look Natural, Please! (1954)

Newly married couple Ralph and Letty Plattin pop into a photographers to have a formal portrait. Ralph is a difficult customer and bugs the photographer by asking why they have to smile for the camera. It’s a convention. Well, of course, but… why, why don’t people accept pics of what they actually look like?

So this sets young Ralph to try his own hand at portrait photography and the rest of the story goes into some detail about the imaginative arrangements Ralph develops for his wedding photographs, the bride’s head emerging from a sheet of card onto which her hair can be brushed in a whorl, later emerging from the large model calyx of a flower against dimmed glass as if floating in water, and so on. The years pass. Plattin’s becomes part of the social season.

Then one night he comes home to his wife very cross. Some whippersnapper came into the shop to have a photo with his wife and started asking a load of damn fool questions, querying the artifice, asking why people don’t want pics of them as they actually are.

The wife stifles a smile. This is the exact same conversation Ralph had with the man who took their honeymoon photograph all those years ago. For a moment she is tempted to remind him. But she has learned the lessons of wifehood and so changes tone, nodding and agreeing with her husband.

So there’s nothing remotely science fiction about this story, it is a comic tale of marital life ending, as so often, with the greater self-awareness and wisdom of the woman acknowledged.

Perforce to Dream (1954)

Jane Kursey submits her first novel to a publisher. She is mortified to discover that a day or so earlier virtually the same story had been submitted by a woman she’s never heard of. The two women meet in the publisher’s office and go for a coffee. Both blame the other for stealing their story.

Only slowly does the omniscient narrator reveal that Jane based the novel on an intense and recurring dream she has in which she wakes on a flowery bank, wearing a dress embroidered with flowers, vividly aware of her body, the earth, the sky, and out of the bushes comes a tall handsome stranger who lays a bouquet on her breast. He leads her to a village where she is well-known and works making beautiful lace. And, so night after night, in her dreams she enters this idyllic Arcadia and embarks on an idyllic romance with this man, finally succumbing to his strong muscles and gentle hands etc and they make love.

That’s what she put into her ‘novel’, the only trouble being that so did her rival, Leila Mortridge. Both are anxious that the other’s knowledge of the dream will end it for them, but both have the usual intense dream experience that night, which reassures them, they stay in touch and, over the coming weeks become friends, though both mystified why they are sharing the same super-vivid dream life.

Then Leila rings with news that a new play is opening, a musical drama, which sounds suspiciously like their shared dream. They nab tickets to attend the opening night where, of course, the entire audience is made up of other young women who have shared the same dream. The curtain goes up on a young actress dressed in a dress embroidered with flowers, lying on a grassy bank, then a handsome stranger emerges from the bushes and lays a bouquet of freshly picked wild flowers on her chest etc. The audience of young women oohs and aahs.

But slowly they become aware of a force up in one of the boxes and when Jane looks up she is thunderstruck to see… him! The handsome man with whom she is having the affair in her dream, with whom she has made love so many times, so beautifully. Slowly the man becomes aware that the entire audience has ceased watching the play and is looking up at him. He registers fear. He rises from his chair and goes to the back of the box but then returns and we see several women closing in on him, reaching for him. With fear in his eyes he climbs out of the box meaning to get across to the next one, but the women reach out, grab his hands and arm, and he plunges down into the stalls.

Later that night Jane rings the magazine where she works. The duty editor says they’re just finishing the man’s obituary. He was Desmond Haley (page 163), a noted psychiatrist and had recently published a paper on inducing mass hallucinations. Clearly that is the (not completely clear) explanation for all these young women having the same vivid dreams. That night the magic dream doesn’t come. It never comes again, to Jane or any other of the romantic dreamers.

Reservation Deferred (1953)

Amanda is 17 and dying. She is a jolly hockey sticks kind of gal and thinks it’s frightfully exciting and everso romantic to be dying, wasting away, like petals falling from a flower. She asks her mummy and daddy and the Reverend Mr Willis and Dr Frobisher and Mrs Day what heaven is going to be like, but none of them really seem to know the details and all adults prefer to change the subject.

One night a ghost appears in her room, a very casual, matter of fact young lady with an ‘admirable figure, slightly red hair, wearing pants and vest. Finding Amanda in the room she apologises and makes to go but Amanda calls her back? Is she a real ghost? Yes. What is her name? Virginia. How did she die? Her husband strangled her, which sounds like murder, but she admits she was everso provocative so a court is trying to reach a final verdict and while it does so she’s left hanging round in limbo.

Amanda is desperate to learn what heaven is like and Virginia says, well it’s divided into areas. There’s a harem area where lots of women clump together wearing see-through trousers and the bearded, turbaned men take their pick. There’s a Nordic area where the women spend all their time binding the wounds of boastful, hard-drinking fighters. There’s the Nirvana section which you can’t even see into because it’s walled off with a sign saying No Women.

Isn’t there a religious section, asks Amanda. Oh yes, Virginia explains, but it’s frightfully boring singing all those hymns, it’s all so ascetic and white, and you have to go home to bed early. Basically heaven seems to have been built for men with little thought for women. And Virginia leaves a completely disillusioned Amanda to cry herself to sleep.

Next morning, having learned that heaven is nothing at all like she thought it would be, Amanda decides to get better, and she does. She grows up into an attractive young woman and marries a fine husband.

So… so is this little comedy biting enough to be a satire? Or is it almost like something you’d read in a good school magazine? Is it in any way at all feminist, insofar as it’s a story of two girls, which references various sexist societies and cultures? Or is it itself deeply sexist in characterising Amanda as a silly and naive schoolgirl, and a good destiny for her being to grow up attractive and marry?

Heaven Scent (1954)

An enjoyable satire on the chemical end of the perfume business, in rather the way The Kraken Wakes includes lots of satire on the news media and Trouble With Lichen is on one level a satire on the beauty industry. Miss Mallison is in love with her boss Mr Alton. He is a charming young inventor who has consistently failed to commercialise any of his rather pat discoveries such as paint which reflects light so well it illuminates a room, or a technique for injecting the seeds of any plant with any flavour.

What he needs, she thinks, is looking after and the love of a good woman. On this particular day he gives her a few bits of work to do then pops out to a meeting with a Mr Grosburger, Solly Grosburger. He runs a successful perfume business, and we learn about the different sectors of the perfume business, from sexy and sultry to sweet innocent 16 (which is the area Solly specialises in).

Alton is doing a fine job of rubbing Solly up the wrong way, going too heavy on the sultry end of the market which Solly isn’t interested in (know your audience, prepare for your interview!) when the situation changes in a flash. Alton produces his product, a tiny vial of clear-looking liquid, asks Solly to get a secretary to bring in a bottle of his bestselling perfume, which she does. Alton opens the bottle, then takes a tiny dropper of his clear liquid and drops it into the perfume bottle. Then asks the secretary if she will dab a little on her handkerchief.

Now, Alton has taken the precaution of stuffing his nostrils with cotton wool, but not so Solly Grosburger. Within seconds he experiences hot flushes, his eyes bulge, he stands, he makes a lunge at the secretary, he starts to declare his undying love for her, how could he never have recognised her beauty, and ends up chasing her round the table while Alton quietly smiles.

Now, the story seems to me a little incoherent. We were told Alton had developed a substance which multiplied the effect of existing perfumes. But no perfume makes you behave like that. It seems closer to the truth to say he’s invented a powerful aphrodisiac. The secretary escapes from the room, Grosburger calms down and immediately starts talking a mega deal with Alton. His future is assured.

Meanwhile, back at the office, Miss Mallison had been pondering the situation and her love for Mr Alton and his apparent ill-fatedness at business. She makes her mind up to act, and goes down to the laboratory where all his inventions are created, asks the lab assistant Mr Dirks to give her the entire supply of the miracle liquid (codename Formula 68), which she bundles up under her mac and takes home.

She returns to her office just in time to greet Mr Alton. He is agog to tell her his good business news but then… suddenly finds himself overwhelmed with love, rushes forward, seizes Miss Mallison by the shoulders, declares his undying love for her. Her plan has worked, and the bottle of the stuff she smuggled home… well, it ought to keep her supplied for a lifetime, a lifetime of having Mr Alton breathlessly fall at her feet in adoration and amour!

More Spinned Against (1953)

Another husband and wife story although it’s about spiders so I didn’t read it.

Thoughts

Most of them aren’t science fiction at all, they’re more tales of the macabre, most of them with a heavily comic spin, and almost all of them also love stories of various forms of satire and bizarreness.

You can see why Wyndham felt so constrained by the format of traditional space opera sci-fi magazines, when his imagination was both much quirkier and much more homely than that:

- quirkier – an artistic monkey with a taste for revenge, a tube train to hell

- homelier – because so many of the stories are about couples or affairs of the heart, even when it’s a deliberately grotesque ‘love affair’ as between Alfred Weston and Una, or the twisted relationship of Mrs Blayne and Lord Solby, or the canny women who get their man (MIss Mallison, Molly Doherty) or the wife who is so much shrewder than her husband (Bronwen Hughes, Letty Plattin)

I hesitate to call them in any way feminist, but he’s definitely a writer fascinated by the subject of love, love affairs and marital relations, and – this is the point – who consistently gives the female point of view and makes his women smarter, shrewder, cleverer and more effective than the often rather dim, self-important men.

Credit

Jizzle by John Wyndham was published by Michael Joseph in 1954. All references are to the 1973 New English Library paperback edition (recommended retail price 30p).

Related link

John Wyndham reviews

- Sleepers of Mars (1973) 5 short stories from the 1930s

- The Day of the Triffids (1951)

- The Kraken Wakes (1953)

- Jizzle (1954) 15 short stories

- The Chrysalids (1955)

- The Seeds of Time (1956) 11 short stories

- The Midwich Cuckoos (1957)

- The Outward Urge (1959)

- Trouble with Lichen (1960)

- Consider Her Ways and Others (1961) 6 short stories

- Chocky (1968)

- Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters by Amy Binns (2019)

Other science fiction reviews

Late Victorian

1888 Looking Backward 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy – Julian West wakes up in the year 2000 to discover a peaceful revolution has ushered in a society of state planning, equality and contentment

1890 News from Nowhere by William Morris – waking from a long sleep, William Guest is shown round a London transformed into villages of contented craftsmen

1895 The Time Machine by H.G. Wells – the unnamed inventor and time traveller tells his dinner party guests the story of his adventure among the Eloi and the Morlocks in the year 802,701

1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells – Edward Prendick is stranded on a remote island where he discovers the ‘owner’, Dr Gustave Moreau, is experimentally creating human-animal hybrids

1897 The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells – an embittered young scientist, Griffin, makes himself invisible, starting with comic capers in a Sussex village, and ending with demented murders

1899 When The Sleeper Wakes/The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells – Graham awakes in the year 2100 to find himself at the centre of a revolution to overthrow the repressive society of the future

1899 A Story of the Days To Come by H.G. Wells – set in the same future London as The Sleeper Wakes, Denton and Elizabeth defy her wealthy family in order to marry, fall into poverty, and experience life as serfs in the Underground city run by the sinister Labour Corps

1900s

1901 The First Men in the Moon by H.G. Wells – Mr Bedford and Mr Cavor use the latter’s invention, an anti-gravity material they call ‘Cavorite’, to fly to the moon and discover the underground civilisation of the Selenites, leading up to its chasteningly moralistic conclusion

1904 The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth by H.G. Wells – scientists invent a compound which makes plants, animals and humans grow to giant size, prompting giant humans to rebel against the ‘little people’

1905 With the Night Mail by Rudyard Kipling – it is 2000 and the narrator accompanies a GPO airship across the Atlantic

1906 In the Days of the Comet by H.G. Wells – a comet passes through earth’s atmosphere and brings about ‘the Great Change’, inaugurating an era of wisdom and fairness, as told by narrator Willie Leadford

1908 The War in the Air by H.G. Wells – Bert Smallways, a bicycle-repairman from Kent, gets caught up in the outbreak of the war in the air which brings Western civilisation to an end

1909 The Machine Stops by E.M. Foster – people of the future live in underground cells regulated by ‘the Machine’ – until one of them rebels

1910s

1912 The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Professor Challenger leads an expedition to a plateau in the Amazon rainforest where prehistoric animals still exist

1912 As Easy as ABC by Rudyard Kipling – set in 2065 in a world characterised by isolation and privacy, forces from the ABC are sent to suppress an outbreak of ‘crowdism’

1913 The Horror of the Heights by Arthur Conan Doyle – airman Captain Joyce-Armstrong flies higher than anyone before him and discovers the upper atmosphere is inhabited by vast jellyfish-like monsters

1914 The World Set Free by H.G. Wells – A history of the future in which the devastation of an atomic war leads to the creation of a World Government, told via a number of characters who are central to the change

1918 The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs – a trilogy of pulp novellas in which all-American heroes battle ape-men and dinosaurs on a lost island in the Antarctic

1920s

1921 We by Evgeny Zamyatin – like everyone else in the dystopian future of OneState, D-503 lives life according to the Table of Hours, until I-330 wakens him to the truth and they rebel

1925 Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov – a Moscow scientist transplants the testicles and pituitary gland of a dead tramp into the body of a stray dog, with disastrous consequences

1927 The Maracot Deep by Arthur Conan Doyle – a scientist, an engineer and a hero are trying out a new bathysphere when the wire snaps and they hurtle to the bottom of the sea, where they discover unimaginable strangeness

1930s

1930 Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon – mind-boggling ‘history’ of the future of mankind over the next two billion years – surely the vastest vista of any science fiction book

1938 Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis – baddies Devine and Weston kidnap Oxford academic, Ransom, and take him in their spherical spaceship to Malacandra, as the natives call the planet Mars, where mysteries and adventures unfold

1940s

1943 Perelandra (Voyage to Venus) by C.S. Lewis – Ransom is sent to Perelandra aka Venus, to prevent Satan tempting the planet’s new young inhabitants to a new Fall as he did on earth

1945 That Hideous Strength by C.S. Lewis – Ransom assembles a motley crew of heroes ancient and modern to combat the rise of an evil corporation which is seeking to overthrow mankind

1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell – after a nuclear war, inhabitants of ruined London are divided into the sheep-like ‘proles’ and members of the Party who are kept under unremitting surveillance

1950s

1950 I, Robot by Isaac Asimov – nine short stories about ‘positronic’ robots, which chart their rise from dumb playmates to controllers of humanity’s destiny

1950 The Martian Chronicles – 13 short stories with 13 linking passages loosely describing mankind’s colonisation of Mars, featuring strange, dreamlike encounters with vanished Martians

1951 Foundation by Isaac Asimov – the first five stories telling the rise of the Foundation created by psychohistorian Hari Seldon to preserve civilisation during the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1951 The Illustrated Man – eighteen short stories which use the future, Mars and Venus as settings for what are essentially earth-bound tales of fantasy and horror

1951 The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham – the whole world turns out to watch the flashing lights in the sky caused by a passing comet and next morning wakes up blind, except for a handful of survivors who have to rebuild human society while fighting off the rapidly growing population of the mobile, intelligent, poison sting-wielding monster plants of the title

1952 Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov – two long stories which continue the future history of the Foundation set up by psycho-historian Hari Seldon as it faces attack by an Imperial general, and then the menace of the mysterious mutant known only as ‘the Mule’

1953 Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov – concluding part of the Foundation Trilogy, which describes the attempt to preserve civilisation after the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1953 Earthman, Come Home by James Blish – the adventures of New York City, a self-contained space city which wanders the galaxy 2,000 years hence, powered by ‘spindizzy’ technology

1953 Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury – a masterpiece, a terrifying anticipation of a future when books are banned and professional firemen are paid to track down stashes of forbidden books and burn them – until one fireman, Guy Montag, rebels

1953 The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester – a fast-moving novel set in a 24th century New York populated by telepaths and describing the mental collapse of corporate mogul Ben Reich who starts by murdering his rival Craye D’Courtney and becomes progressively more psychotic as he is pursued by telepathic detective, Lincoln Powell

1953 Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke one of my favourite sci-fi novels, a thrilling narrative describing the ‘Overlords’ who arrive from space to supervise mankind’s transition to the next stage in its evolution

1953 The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham – some form of alien life invades earth in the shape of ‘fireballs’ from outer space which fall into the deepest parts of the earth’s oceans, followed by the sinking of ships passing over the ocean deeps, gruesome attacks of ‘sea tanks’ on ports and shoreline settlements around the world and then, in the final phase, the melting of the earth’s icecaps and global flooding

1954 The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov – set 3,000 years in the future when humans have separated into ‘Spacers’ who have colonised 50 other planets, and the overpopulated earth whose inhabitants live in enclosed cities or ‘caves of steel’, and introducing detective Elijah Baley who is tasked with solving a murder mystery

1954 Jizzle by John Wyndham – 15 short stories, from the malevolent monkey of the title story to a bizarre yarn about a tube train which goes to hell, a paychiatrist who projects the same idyllic dream into the minds of hundreds of women around London, to a dry run for The Chrysalids

1955 The Chrysalids by John Wyndham – hundreds of years after a nuclear war devastated North America, David Strorm grows up in a rural community run by God-fearing zealots obsessed with detecting mutant plants, livestock and – worst of all – human ‘blasphemies’ – caused by lingering radiation; but as he grows up, David realises he possesses a special mutation the Guardians of Purity have never dreamed of – the power of telepathy – and he’s not the only one, and soon he and his mind-melding friends are forced to flee to the Badlands in a race to survive

1956 The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov – 3,000 years in the future detective Elijah Baley returns, with his robot sidekick, R. Daneel Olivaw, to solve a murder mystery on the remote planet of Solaria

— Some problems with Isaac Asimov’s science fiction

1956 They Shall Have Stars by James Blish – explains the invention, in the near future, of i) the anti-death drugs and ii) the spindizzy technology which allow the human race to colonise the galaxy

1956 The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester – a fast-paced phantasmagoria set in the 25th century where humans can teleport, a terrifying new weapon has been invented, and tattooed hard-man, Gulliver Foyle, is looking for revenge

1956 The Death of Grass by John Christopher – amid the backdrop of a worldwide famine caused by the Chung-Li virus which kills all species of grass (wheat, barley, oats etc) decent civil engineer John Custance finds himself leading his wife, two children and a small gang of followers out of London and across an England collapsing into chaos and barbarism in order to reach the remote valley which his brother had told him he was going to plant with potatoes and other root vegetables and which he knows is an easily defendable enclave

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham – one night a nondescript English village is closed off by a force field, all the inhabitants within the zone losing consciousness. A day later the field disappears and the villagers all regain consciousness but two months later, all the fertile women in the place realise they are pregnant, and nine months later give birth to identical babies with platinum blonde hair and penetrating golden eyes, which soon begin exerting telepathic control over their parents and then the other villagers. Are they aliens, implanted in human wombs, and destined to supersede Homo sapiens as top species on the planet?

1959 The Triumph of Time by James Blish – concluding novel of Blish’s ‘Okie’ tetralogy in which mayor of New York John Amalfi and his friends are present at the end of the universe

1959 The Sirens of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut – Winston Niles Rumfoord builds a space ship to explore the solar system where encounters a chrono-synclastic infundibula, and this is just the start of a bizarre meandering fantasy which includes the Army of Mars attacking earth and the adventures of Boaz and Unk in the caverns of Mercury

1959 The Outward Urge by John Wyndham – a conventional space exploration novel in five parts which follow successive members of the Troon family over a 200-year period (1994 to 2194) as they help build the first British space station, command the British moon base, lead expeditions to Mars, to Venus, and ends with an eerie ‘ghost’ story

1960s

1960 Trouble With Lichen by John Wyndham – ardent feminist and biochemist Diana Brackley discovers a substance which slows down the ageing process, with potentially revolutionary implications for human civilisation, in a novel which combines serious insights into how women are shaped and controlled by society and sociological speculation with a sentimental love story and passages of broad social satire (about the beauty industry and the newspaper trade)

1961 A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke a pleasure tourbus on the moon is sucked down into a sink of moondust, sparking a race against time to rescue the trapped crew and passengers

1961 Consider Her Ways and Others by John Wyndham – Six short stories dominated by the title track which depicts England a few centuries hence, after a plague has wiped out all men and the surviving women have been genetically engineered into four distinct types, the brainy Doctors, the brawny Amazons, the short Servitors, and the vast whale-like mothers into whose body a twentieth century woman doctor is unwittingly transported

1962 The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – Dr Kerans is part of a UN mission to map the lost cities of Europe which have been inundated after solar flares melted the worlds ice caps and glaciers, but finds himself and his colleagues’ minds slowly infiltrated by prehistoric memories of the last time the world was like this, complete with tropical forest and giant lizards, and slowly losing their grasp on reality.

1962 The Voices of Time and Other Stories – Eight of Ballard’s most exquisite stories including the title tale about humanity slowly falling asleep even as they discover how to listen to the voices of time radiating from the mountains and distant stars, or The Cage of Sand where a handful of outcasts hide out in the vast dunes of Martian sand brought to earth as ballast which turned out to contain fatal viruses. Really weird and visionary.

1962 A Life For The Stars by James Blish – third in the Okie series about cities which can fly through space, focusing on the coming of age of kidnapped earther, young Crispin DeFord, aboard space-travelling New York

1962 The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick In an alternative future America lost the Second World War and has been partitioned between Japan and Nazi Germany. The narrative follows a motley crew of characters including a dealer in antique Americana, a German spy who warns a Japanese official about a looming surprise German attack, and a woman determined to track down the reclusive author of a hit book which describes an alternative future in which America won the Second World War

1962 Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut – the memoirs of American Howard W. Campbell Jr. who was raised in Germany and has adventures with Nazis and spies

1963 Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut – what starts out as an amiable picaresque as the narrator, John, tracks down the so-called ‘father of the atom bomb’, Felix Hoenniker for an interview turns into a really bleak, haunting nightmare where an alternative form of water, ice-nine, freezes all water in the world, including the water inside people, killing almost everyone and freezing all water forever

1964 The Drought by J.G. Ballard – It stops raining. Everywhere. Fresh water runs out. Society breaks down and people move en masse to the seaside, where fighting breaks out to get near the water and set up stills. In part two, ten years later, the last remnants of humanity scrape a living on the vast salt flats which rim the continents, until the male protagonist decides to venture back inland to see if any life survives

1964 The Terminal Beach by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s breakthrough collection of 12 short stories which, among more traditional fare, includes mind-blowing descriptions of obsession, hallucination and mental decay set in the present day but exploring what he famously defined as ‘inner space’

1964 Dr. Strangelove, or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb by Peter George – a novelisation of the famous Kubrick film, notable for the prologue written as if by aliens who arrive in the distant future to find an earth utterly destroyed by the events described in the main narrative

1966 Rocannon’s World by Ursula Le Guin – Le Guin’s first novel, a ‘planetary romance’ or ‘science fantasy’ set on Fomalhaut II where ethnographer and ‘starlord’ Gaverel Rocannon rides winged tigers and meets all manner of bizarre foes in his quest to track down the aliens who destroyed his spaceship and killed his colleagues, aided by sword-wielding Lord Mogien and a telepathic Fian

1966 Planet of Exile by Ursula Le Guin – both the ‘farborn’ colonists of planet Werel, and the surrounding tribespeople, the Tevarans, must unite to fight off the marauding Gaal who are migrating south as the planet enters its deep long winter – not a good moment for the farborn leader, Jakob Agat Alterra, to fall in love with Rolery, the beautiful, golden-eyed daughter of the Tevaran chief

1966 – The Crystal World by J.G. Ballard – Dr Sanders journeys up an African river to discover that the jungle is slowly turning into crystals, as does anyone who loiters too long, and becomes enmeshed in the personal psychodramas of a cast of lunatics and obsessives

1967 The Disaster Area by J.G. Ballard – Nine short stories including memorable ones about giant birds and the man who sees the prehistoric ocean washing over his quite suburb.

1967 City of Illusions by Ursula Le Guin – an unnamed humanoid with yellow cat’s eyes stumbles out of the great Eastern Forest which covers America thousands of years in the future when the human race has been reduced to a pitiful handful of suspicious rednecks or savages living in remote settlements. He is discovered and nursed back to health by a relatively benign commune but then decides he must make his way West in an epic trek across the continent to the fabled city of Es Toch where he will discover his true identity and mankind’s true history

1966 The Anti-Death League by Kingsley Amis –

1968 2001: A Space Odyssey a panoramic narrative which starts with aliens stimulating evolution among the first ape-men and ends with a spaceman being transformed into a galactic consciousness

1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick – in 1992 androids are almost indistinguishable from humans except by trained bounty hunters like Rick Deckard who is paid to track down and ‘retire’ escaped ‘andys’ – earning enough to buy mechanical animals, since all real animals died long ago

1968 Chocky by John Wyndham – Matthew is the adopted son of an ordinary, middle-class couple who starts talking to a voice in his head who it takes the entire novel to persuade his parents is real and a telepathic explorer from a far distant planet

1969 The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton – describes in retrospect, in the style of a scientific inquiry, the crisis which unfolds after a fatal virus is brought back to earth by a space probe and starts spreading uncontrollably

1969 Ubik by Philip K. Dick – in 1992 the world is threatened by mutants with psionic powers who are combated by ‘inertials’. The novel focuses on the weird alternative world experienced by a group of inertials after they are involved in an explosion on the moon

1969 The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin – an envoy from the Ekumen or federation of advanced planets – Genly Ai – is sent to the planet Gethen to persuade its inhabitants to join the federation, but the focus of the book is a mind-expanding exploration of the hermaphroditism of Gethen’s inhabitants, as Genly is forced to undertake a gruelling trek across the planet’s frozen north with the disgraced native lord, Estraven, during which they develop a cross-species respect and, eventually, a kind of love

1969 Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut – Vonnegut’s breakthrough novel in which he manages to combine his personal memories of being an American POW of the Germans and witnessing the bombing of Dresden in the character of Billy Pilgrim, with a science fiction farrago about Tralfamadorians who kidnap Billy and transport him through time and space – and introduces the catchphrase ‘so it goes’

1970s

1970 Tau Zero by Poul Anderson – spaceship Leonora Christine leaves earth with a crew of fifty to discover if humans can colonise any of the planets orbiting the star Beta Virginis, but when its deceleration engines are damaged, the crew realise they need to exit the galaxy altogether in order to find space with low enough radiation to fix the engines – and then a series of unfortunate events mean they find themselves forced to accelerate faster and faster, effectively travelling forwards through time as well as space until they witness the end of the entire universe – one of the most thrilling sci-fi books I’ve ever read

1970 The Atrocity Exhibition by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s best book, a collection of fifteen short experimental texts in stripped-down prose bringing together key obsessions like car crashes, mental breakdown, World War III, media images of atrocities and clinical sex

1971 Vermilion Sands by J.G. Ballard – nine short stories including Ballard’s first, from 1956, most of which follow the same pattern, describing the arrival of a mysterious, beguiling woman in the fictional desert resort of Vermilion Sands, the setting for extravagantly surreal tales of the glossy, lurid and bizarre

1971 The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula Le Guin – thirty years in the future (in 2002) America is an overpopulated environmental catastrophe zone where meek and unassuming George Orr discovers that his dreams can alter reality, changing history at will. He comes under the control of visionary neuro-scientist, Dr Haber, who sets about using George’s powers to alter the world for the better, with unanticipated and disastrous consequences

1971 Mutant 59: The Plastic Eater by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis – a genetically engineered bacterium starts eating the world’s plastic, leading to harum scarum escapades in disaster-stricken London

1972 The Word for World Is Forest by Ursula Le Guin – novella set on the planet Athshe describing its brutal colonisation by exploitative Terrans (who call it ‘New Tahiti’) and the resistance of the metre-tall, furry, native population of Athsheans, with their culture of dreamtime and singing

1972 The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe – a mind-boggling trio of novellas set on a pair of planets 20 light years away, the stories revolve around the puzzle of whether the supposedly human colonists are, in fact, the descendants of the planets’ shape-shifting aboriginal inhabitants who murdered the first earth colonists and took their places so effectively that they have forgotten the fact and think themselves genuinely human

1973 Crash by J.G. Ballard – Ballard’s most ‘controversial’ novel, a searingly intense description of its characters’ obsession with the sexuality of car crashes, wounds and disfigurement

1973 Rendezvous With Rama by Arthur C. Clarke – in 2031 a 50-kilometre-long object of alien origin enters the solar system, so the crew of the spaceship Endeavour are sent to explore it in one of the most haunting and evocative novels of this type ever written

1973 Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut – Vonnegut’s longest and most experimental novel with the barest of plots and characters allowing him to sound off about sex, race, America, environmentalism, with the appearance of his alter ego Kilgore Trout and even Vonnegut himself as a character, all enlivened by Vonnegut’s own naive illustrations and the throwaway catchphrase ‘And so on…’

1973 The Best of John Wyndham 1932 to 1949 – Six rather silly short stories dating, as the title indicates, from 1932 to 1949, with far too much interplanetary travel

1974 Concrete Island by J.G. Ballard – the short and powerful novella in which an advertising executive crashes his car onto a stretch of wasteland in the juncture of three motorways, finds he can’t get off it, and slowly adapts to life alongside its current, psychologically damaged inhabitants

1974 Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick – America after the Second World War is a police state but the story is about popular TV host Jason Taverner who is plunged into an alternative version of this world where he is no longer a rich entertainer but down on the streets among the ‘ordinaries’ and on the run from the police. Why? And how can he get back to his storyline?

1974 The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin – in the future and 11 light years from earth, the physicist Shevek travels from the barren, communal, anarchist world of Anarres to its consumer capitalist cousin, Urras, with a message of brotherhood and a revolutionary new discovery which will change everything

1974 Inverted World by Christopher Priest – vivid description of a city on a distant planet which must move forwards on railway tracks constructed by the secretive ‘guilds’ in order not to fall behind the mysterious ‘optimum’ and avoid the fate of being obliterated by the planet’s bizarre lateral distorting, a vivid and disturbing narrative right up until the shock revelation of the last few pages

1975 High Rise by J.G. Ballard – an astonishingly intense and brutal vision of how the middle-class occupants of London’s newest and largest luxury, high-rise development spiral down from petty tiffs and jealousies into increasing alcohol-fuelled mayhem, disintegrating into full-blown civil war before regressing to starvation and cannibalism

1976 The Alteration by Kingsley Amis – a counterfactual narrative in which the Reformation never happened and so there was no Enlightenment, no Romantic revolution, no Industrial Revolution spearheaded by Protestant England, no political revolutions, no Victorian era when democracy and liberalism triumphed over Christian repression, with the result that England in 1976 is a peaceful medieval country ruled by officials of the all-powerful Roman Catholic Church

1976 Slapstick by Kurt Vonnegut – a madly disorientating story about twin freaks, a future dystopia, shrinking Chinese and communication with the afterlife

1979 The Unlimited Dream Company by J.G. Ballard – a strange combination of banality and visionary weirdness as an unhinged young man crashes his stolen plane in suburban Shepperton, and starts performing magical acts like converting the inhabitants into birds, conjuring up exotic foliage, convinced he is on a mission to liberate them

1979 Jailbird by Kurt Vonnegut – the satirical story of Walter F. Starbuck and the RAMJAC Corps run by Mary Kathleen O’Looney, a baglady from Grand Central Station, among other satirical notions, including the news that Kilgore Trout, a character who recurs in most of his novels, is one of the pseudonyms of a fellow prisoner at the gaol where Starbuck ends up serving a two year sentence, one Dr Robert Fender

1980s

1980 Russian Hide and Seek by Kingsley Amis – set in an England of 2035 after a) the oil has run out and b) a left-wing government left NATO and England was promptly invaded by the Russians in the so-called ‘the Pacification’, who have settled down to become a ruling class and treat the native English like 19th century serfs

1980 The Venus Hunters by J.G. Ballard – seven very early and often quite cheesy sci-fi short stories, along with a visionary satire on Vietnam (1969), and then two mature stories from the 1970s which show Ballard’s approach sliding into mannerism

1981 The Golden Age of Science Fiction edited by Kingsley Amis – 17 classic sci-fi stories from what Amis considers the ‘Golden Era’ of the genre, basically the 1950s

1981 Hello America by J.G. Ballard – a hundred years from now an environmental catastrophe has turned America into a vast desert, except for west of the Rockies which has become a rainforest of Amazonian opulence, and it is here that a ragtag band of explorers from old Europe discover a psychopath has crowned himself ‘President Manson’, revived an old nuclear power station to light up Las Vegas and plays roulette in Caesar’s Palace to decide which American city to nuke next

1981 The Affirmation by Christopher Priest – an extraordinarily vivid description of a schizophrenic young man living in London who, to protect against the trauma of his actual life (father died, made redundant, girlfriend committed suicide) invents a fantasy world, the Dream Archipelago, and how it takes over his ‘real’ life

1982 Myths of the Near Future by J.G. Ballard – ten short stories showing Ballard’s range of subject matter from Second World War China to the rusting gantries of Cape Kennedy

1982 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke – Heywood Floyd joins a Russian spaceship on a two-year journey to Jupiter to a) reclaim the abandoned Discovery and b) investigate the monolith on Japetus

1984 Empire of the Sun by J.G. Ballard – his breakthrough book, ostensibly an autobiography focusing on this 1930s boyhood in Shanghai and then incarceration in a Japanese internment camp, observing the psychological breakdown of the adults around him: made into an Oscar-winning movie by Steven Spielberg: only later did it emerge that the book was intended as a novel and is factually misleading

1984 Neuromancer by William Gibson – Gibson’s stunning debut novel which establishes the ‘Sprawl’ universe, in which burnt-out cyberspace cowboy, Case, is lured by ex-hooker Molly into a mission led by ex-army colonel Armitage to penetrate the secretive corporation, Tessier-Ashpool, at the bidding of the vast and powerful artificial intelligence, Wintermute

1986 Burning Chrome by William Gibson – ten short stories, three or four set in Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ universe, the others ranging across sci-fi possibilities, from a kind of horror story to one about a failing Russian space station

1986 Count Zero by William Gibson – second in the ‘Sprawl trilogy’: Turner is a tough expert at kidnapping scientists from one mega-tech corporation for another, until his abduction of Christopher Mitchell from Maas Biolabs goes badly wrong and he finds himself on the run, his storyline dovetailing with those of sexy young Marly Krushkhova, ‘disgraced former owner of a tiny Paris gallery’ who is commissioned by the richest man in the world to track down the source of a mysterious modern artwork, and Bobby Newmark, self-styled ‘Count Zero’ and computer hacker

1987 The Day of Creation by J.G. Ballard – strange and, in my view, profoundly unsuccessful novel in which WHO doctor John Mallory embarks on an obsessive quest to find the source of an African river accompanied by a teenage African girl and a half-blind documentary maker who films the chaotic sequence of events

1987 2061: Odyssey Three by Arthur C. Clarke – Spaceship Galaxy is hijacked and forced to land on Europa, moon of the former Jupiter, in a ‘thriller’ notable for Clarke’s descriptions of the bizarre landscapes of Halley’s Comet and Europa

1988 Memories of the Space Age Eight short stories spanning the 20 most productive years of Ballard’s career, presented in chronological order and linked by the Ballardian themes of space travel, astronauts and psychosis

1988 Running Wild by J.G. Ballard – the pampered children of a gated community of affluent professionals, near Reading, run wild and murder their parents and security guards

1988 Mona Lisa Overdrive by William Gibson – third of Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ trilogy in which street-kid Mona is sold by her pimp to crooks who give her plastic surgery to make her look like global simstim star Angie Marshall, who they plan to kidnap; but Angie is herself on a quest to find her missing boyfriend, Bobby Newmark, one-time Count Zero; while the daughter of a Japanese gangster, who’s been sent to London for safekeeping, is abducted by Molly Millions, a lead character in Neuromancer

1990s

1990 War Fever by J.G. Ballard – 14 late short stories, some traditional science fiction, some interesting formal experiments like Answers To a Questionnaire from which you have to deduce the questions and the context

1990 The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling – in an alternative version of history, Victorian inventor Charles Babbage’s design for an early computer, instead of remaining a paper theory, was actually built, drastically changing British society, so that by 1855 it is led by a party of industrialists and scientists who use databases and secret police to keep the population suppressed

1991 The Kindness of Women by J.G. Ballard – a sequel of sorts to Empire of the Sun which reprises the Shanghai and Japanese internment camp scenes from that book, but goes on to describe the author’s post-war experiences as a medical student at Cambridge, as a pilot in Canada, his marriage, children, writing and involvement in the avant-garde art scene of the 1960s and 70s: though based on his own experiences the book is overtly a novel focusing on a small number of recurring characters who symbolise different aspects of the post-war world

1993 Virtual Light by William Gibson – first of Gibson’s Bridge Trilogy, in which cop-with-a-heart-of-gold Berry Rydell foils an attempt by crooked property developers to rebuild post-earthquake San Francisco

1994 Rushing to Paradise by J.G. Ballard – a sort of rewrite of Lord of the Flies in which a number of unbalanced environmental activists set up a utopian community on a Pacific island, ostensibly to save the local rare breed of albatross from French nuclear tests, but end up going mad and murdering each other

1996 Cocaine Nights by J. G. Ballard – sensible, middle-class Charles Prentice flies out to a luxury resort for British ex-pats on the Spanish Riviera to find out why his brother, Frank, is in a Spanish prison charged with murder, and discovers the resort has become a hotbed of ‘transgressive’ behaviour – i.e. sex, drugs and organised violence – which has come to bind the community together

1996 Idoru by William Gibson – second novel in the ‘Bridge’ trilogy: Colin Laney has a gift for spotting nodal points in the oceans of data in cyberspace, and so is hired by the scary head of security for a pop music duo, Lo/Rez, to find out why his boss, the half-Irish singer Rez, has announced he is going to marry a virtual reality woman, an idoru; meanwhile schoolgirl Chia MacKenzie flies out to Tokyo and unwittingly gets caught up in smuggling new nanotechnology device which is the core of the plot

1999 All Tomorrow’s Parties by William Gibson – third of the Bridge Trilogy in which main characters from the two previous books are reunited on the ruined Golden Gate bridge, including tough ex-cop Rydell, sexy bike courier Chevette, digital babe Rei Toei, Fontaine the old black dude who keeps an antiques shop, as a smooth, rich corporate baddie seeks to unleash a terminal shift in the world’s dataflows and Rydell is hunted by a Taoist assassin

2000s

2000 Super-Cannes by J.G. Ballard – Paul Sinclair packs in his London job to accompany his wife, who’s landed a plum job as a paediatrician at Eden-Olympia, an elite business park just outside Cannes in the South of France; both are unnerved to discover that her predecessor, David Greenwood, one day went to work with an assault rifle, shot dead several senior executives before shooting himself; when Paul sets out to investigate, he discovers the business park is a hotbed of ‘transgressive’ behaviour i.e. designer drugs, BDSM sex, and organised vigilante violence against immigrants down in Cannes, and finds himself and his wife being sucked into its disturbing mind-set

2003 Pattern Recognition by William Gibson – first of the ‘Blue Ant’ trilogy, set very much in the present, around the London-based advertising agency Blue Ant, founded by advertising guru Hubertus Bigend who hires Cayce Pollard, supernaturally gifted logo approver and fashion trend detector, to hunt down the maker of mysterious ‘footage’ which has started appearing on the internet, a quest that takes them from New York and London, to Tokyo, Moscow and Paris

2007 Spook Country by William Gibson – second in the ‘Blue Ant’ trilogy

2008 Miracles of Life by J.G. Ballard – right at the end of his life, Ballard wrote a straightforward autobiography in which he makes startling revelations about his time in the Japanese internment camp (he really enjoyed it!), insightful comments about science fiction, but the real theme is his moving expressions of love for his three children