…. grabbing at the straw… straining to hear… the odd word… make some sense of it… whole body like gone… just the mouth… like maddened… and can’t stop… no stopping it… something she – … something she had to –

… what?… who?… no!… she!…

Remember how episodes of the American sitcom Friends were named ‘The one where….’, well, this Beckett play is ‘the one where’ almost the entire stage is in darkness except for the face of a woman, in fact just her mouth, a woman’s mouth illuminated by one tight spotlight while she declaims a fragmented panic-stricken monologue at breathless speed.

Mise-en-scène

As with all Beckett’s ‘plays’ from 1960 or so onwards, the stage directions are extremely precise, because Not I is, arguably, less a play than a piece of performance art which happens to be taking place in a theatre:

Stage in darkness but for MOUTH, upstage audience right, about 8 feet above stage level, faintly lit from close-up and below, rest of face in shadow. Invisible microphone. AUDITOR, downstage audience left, tall standing figure, sex undeterminable, enveloped from head to foot in loose black djellaba, with hood, fully faintly lit, standing on invisible podium about 4 feet high shown by attitude alone to be facing diagonally across stage intent on MOUTH, dead still throughout but for four brief movements where indicated. See Note. As house lights down MOUTH ‘s voice unintelligible behind curtain. House lights out. Voice continues unintelligible behind curtain, 10 seconds: With rise of curtain ad-libbing from text as required leading when curtain fully up and attention sufficient

into:

Into the ceaseless flow of verbiage coming out of MOUTH’s mouth. As to ‘See Note’, the Note says:

Movement: this consists in simple sideways raising of arms from sides and their falling back, in a gesture of helpless compassion. It lessens with each recurrence till scarcely perceptible at third. There is just enough pause to contain it as MOUTH recovers from vehement refusal to relinquish third person.

So two people are onstage, a woman about 8 feet above the stage to the right and a tall figure standing 4 feet above the stage on the left.

In my review of Breath I wrote about the importance of exact stage directions in Beckett’s plays and the sense you often have that the staging and the stage directions virtually overshadow the actual content of the plays. Not I is a classic example of this, in that there is content, the mouth does say thing of consequence and import – but it is all dwarfed by the intensity of the conception and of the extremely precise and very vivid stage directions.

Content

So what is this voice ceasely reciting at such high speed? Well, like so many other Beckett texts it is built out of the repetition of key phrases, pretty banal in themselves, which quickly accumulate a freight of meaning, ominous overtones, and which are told in a high voltage, jerky panic. The opening few lines give a complete flavour:

out… into this world… this world… tiny little thing… before its time… in a god for- … what?… girl?… yes… tiny little girl… into this… out into this… before her time… godforsaken hole called… called… no matter… parents unknown… unheard of…

It sounds like yet another deranged Beckett consciousness, an Alzheimer’s victim, feverishly piecing together fragments of memory, torn by incessant questions she addresses to herself, who? why? what? and moments of panic:

… what?… who?… no !.. she !..

There is a passage about punishment and sin, and the fact she’d been brought up to believe in ‘a merciful God’.

… thing she understood perfectly … that notion of punishment … which had first occurred to her … brought up as she had been to believe .. . with the other waifs … in a merciful . . . [Brief laugh. ] .. . God … [Good laugh. ]

She sounds like one of the old ladies from Beckett’s childhood in rural Ireland, except with a thoroughly modern hysteria, complaining about the sounds in her skull, the relentless buzzing, and then… a passage about how she couldn’t scream, some problem with screaming, screaming, which leads up to her harrowing actual screams:

… never got the message… or powerless to respond… like numbed… couldn’t make the sound… not any sound… no sound of any kind… no screaming for help for example… should she feel so inclined… scream… [Screams. ]… then listen… [Silence. ]… scream again… [Screams again.]

The frenzy of the ceaseless wording leading up to the four movements from the AUDITOR, which occur during the silences after the woman works herself up to a frenzy or short, staccato, terrified words, almost as if she’s having a seizure, a fit:

.. the buzzing?.. yes… all dead still but for the buzzing… when suddenly she realized… words were – … what ?.. who?.. no !.. she!..

She appears to be sent shopping as a girl but stands dumb and terrified giving her bag to a man who does it all for her, it takes a while to realise that this is one of about four scenarios which the flood of fragmented memories seem to be reconstructing.

But specific memories tend to be eclipsed by descriptions of the voice itself, of the experience of being hag-ridden and driven by the voice by the mouth, no idea what she’s saying but can’t stop:

just the mouth… lips… cheeks… jaws… never-… what?.. tongue?.. yes… lips… cheeks… jaws… tongue… never still a second… mouth on fire… stream of words… in her ear… practically in her ear… not catching the half… not the quarter… no idea what she’s saying… imagine!.. no idea what she ‘s saying!.. and can’t stop… no stopping it… she who but a moment before… but a moment!.. could not make a sound… no sound of any kind… now can’t stop… imagine!.. can’t stop the stream… and the whole brain begging… something begging in the brain… begging the mouth to stop… pause a moment… if only for a moment… and no response… as if it hadn’t heard… or couldn’t… couldn’t pause a second… like maddened… all that together… straining to hear… piece it together… and the brain… raving away on its own… trying to make sense of it… or make it stop…

God, it’s a vision of intense horror, despair, astonishing intensity, a soul driven, endlessly driven on, by what she keeps describing as a buzzing inside her skull, very much the motive of Beckett’s many monologuists since The Unnameable who hear a voice compelling them to speak, think, make sense of the endless voice compelling words within their skulls, the motive force behind so many of Beckett’s skullscapes. One critic, Vivian Mercier, suggests that Not I is, in effect, a placing on stage of the prose experience of The Unnameable a dramatisation of the same terrible compulsion.

… something she had to -… what?… the buzzing?… yes… all the time the buzzing… dull roar… in the skull…

Another important element is the way MOUTH appears, in these fragmentary memories or anecdotes, to be talking about herself and describing herself in the third person, a common symptom of mental illness, observing memories of their own lives with detachment as if they happened to someone else.

In this mood she seems to be referring to herself when she talks about the tiny little thing, the wee bairn, the tiny mite, born into a world of woe, illegitimate and rejected… and then jumps to herself as an old lady, surprised at her own age:

coming up to sixty when – … what?.. seventy?.. good God !.. coming up to seventy…

An old lady, her mind completely gone, fragments of memories, trying to make sense, driven on by the incessant buzzing in her skull.

This alienation from herself rises to a terrifying climax at each of the punctuation points when she pauses a moment and the other figure on the stage makes its strange hieratic gesture. Each time the crisis is signalled by a formula of the same four words, the last of which is ‘she’, as if MOUTH is seized with panic-horror by it, the Other, herself as other, her maenad voice.

… what?.. who ?.. no!.. she !..

The final section gives a bit more biography, how she was always a silent child, almost a mute, but just occasionally experienced the sudden urge to speak and had to rush outside, rushed into the outdoors lavatory, spewed it all up. That was the root, the precursor of the plight she is in now:

… now this… this… quicker and quicker… the words… the brain… flickering away like mad… quick grab and on… nothing there… on somewhere else… try somewhere else… all the time something begging… something in her begging… begging it all to stop…

God, the horror. Beckett told the American actress Jessica Tandy he hoped that the piece would ‘work on the nerves of the audience, not its intellect’ and it certainly sets my nerves jangling.

Not I

… what?.. who ?.. no!.. she !..

This is the rationale for the title, Not I. On one level the piece is not exactly a systematic ‘investigation’ but a terrifying dramatisation of the way all of us are aware not only of our ‘selves’, but of other elements in our minds which we, on the whole, manage or reject, the host of alternative suggestions, the way we are inside ourselves and yet, at various moments, are also capable of seeing ourselves as if from the outside.

This is busy territory, and over the past two and a half thousand years a host of philosophers and, more recently, psychologists, have developed all manner of theories about how the mind develops and, in particular, manages the dichotomy of being an I which perceives but also developing the awareness that this I exists in a world which is mostly Not I. In its entry of Not I the Faber Companion to Samuel Beckett refers to the theories of:

- Schopenhauer, for whom perception of the external world was always accompanied by a sense that it is not I

- Nordau‘s theory of the development of the psyche which first defines itself but as it conceptualises and understands the external world, the I retreats behind the Not I

- St Paul Corinthians 15:10: ‘But by the grace of God I am what I am: and his grace which was bestowed upon me was not in vain; but I laboured more abundantly than they all: yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me.’

- Jakob Böhme, asked by what authority he wrote, replied: ‘Not I, the I that I am, knows these things, but God knows them in me’ (page 412)

Of these, I like the St Paul quote. If it bears any relation to this play it is the notion that I am that I am but I am not I, I am only I by virtue of another, of the Not I. Hence the shadowy Other sharing the stage.

But there’s no end to the concordances and echoes of these two words which can be found in the world’s literature and theology and philosophy – but most people are aware of there being levels of their selves, or of it being fragmented into peripheral, casual elements which we can easily dismiss, spectruming through to core elements of our selves which we cling on to and consider essential.

The Mouth’s monologue dramatises a set of four big moments which come back to her in fragments after some kind of epiphany or trigger moment in a field full of cowslips to the sound of larks. They are:

- being born a little thing

- crying on her hands one summer day in Croker’s acre

- being sent to do the shopping in some shopping centre

- in court

But really these moments serve to bring out the troubled relationship between the core being, whatever you want to call it, and those other moments, those other aspects of our personalities, everything which is ‘Not I’.

Of course in the play as conceived there is a physical embodiment of Not I onstage, namely the other figure. The way it raises its arms ‘in a gesture of helpless compassion’ at the four moments when Mouth stutters to a horrified silence, suggests they are linked. Is the figure Death, a Guardian Angel, the speaker’s Id or Superego? You pays your money and you takes your choice, but there’s no doubting the importance of the dynamic relationship between the two figures, an I and a Not I. Or maybe two Is which both possess Not Is. Or maybe they are two parts of the same I…

The Billie Whitelaw production

Beckett’s muse, the actress Billie Whitelaw, didn’t give the piece’s premiere, but starred in its first London performance in 1973. This was then recreated in order to be filmed in 1975 and can be found on YouTube.

I think this is spectacular, what a spectacular, amazing performance, what an experience, how disorientating, how revolting the way that, after a while the mouth seems to morph into some disgusting animal, and the endless mad demented drivel, the breathless haste in Whitelaw’s voice rising to the recurrent shout of SHE!! God, the horror.

Although very sexy and feminine when she wanted to be, Whitelaw also had a no-nonsense, working class toughness about her, a strong northern accent (she grew up in a working class area of Bradford) which slips out throughout the recitation.

But her real toughness comes over in those four big cries of SHE!!, delivered much deeper and ballsier than softer actresses, and so giving it a real terror.

Once you get over the sheer thrill of the performance there is an obvious feature about it which is that it largely ignores Beckett’s stage directions. In the piece as conceived there is a dynamic tension between the speaking woman on the right of the stage and the androgynous cloaked figure to the left who responds to the four big hysterical climaxes of the monologue with the mysterious, slow-motion raising and lowering of the arms gesture.

The oddity is that Whitelaw’s performance benefited from extensive coaching from Beckett. So why did he completely jettison a key part of the initial concept? Did he realise it was distracting from the core idea of the spotlight on a ceaselessly talking mouth? Apparently so because, according to the Wikipedia article:

When Beckett came to be involved in staging the play, he found that he was unable to place the Auditor in a stage position that pleased him, and consequently allowed the character to be omitted from those productions. However, he chose not to cut the character from the published script, and whether or not the character is used in production seems to be at the discretion of individual producers. As he wrote to two American directors in 1986: “He is very difficult to stage (light–position) and may well be of more harm than good. For me the play needs him but I can do without him. I have never seen him function effectively.”

Staging the production presented extreme difficulties for the leading lady.

Initially Billie Whitelaw wanted to stand on a dais but she found this didn’t work for her so she allowed herself to be strapped in a chair called an ‘artist’s rest’ on which a film actor wearing armour rests because he cannot sit down. Her entire body was draped in black; her face covered with black gauze with a black transparent slip for her eyes and her head was clamped between two pieces of sponge rubber so that her mouth would remain fixed in the spotlight. Finally a bar was fixed which she could cling to and on to which she could direct her tension. She was unable to use a visual aid and so memorised the text.

Regarding selves and unselves, it is a maybe a profound insight that, although Whitelaw found is a desperately difficult role and was, after the initial rehearsals, seriously disorientated, she came to regard it as one of her most powerful performances because it unlocked something inside her,

She heard in Mouth’s outpourings her own ‘inner scream’: ‘I found so much of my self in Not I.’

Maybe we all do. Maybe that’s one function of art, allowing us to discover the Not I in all of us.

A touch of autobiography

I grew up above the village grocery shop and sub-post office my parents ran, and across the road and through some woodland was a priory which had been turned into an old people’s home which was still run by nuns, old nuns, very old nuns, in fact most of the nuns were too old and infirm to make it the couple of hundred yards through the trees up to the road they had to cross to get to the shop and some of the nuns and old ladies who could make it up weren’t too confident crossing the road, not least Miss Luck (real name) who was very short-sighted, almost blind, who would arrive at the road and just set out across it regardless of traffic, so that the first thing all the new staff in the shop were taught was, ‘If you see Miss Luck arrive at the gate from the Priory, drop everything and run across the road to help her walk across without being run over’.

And so I watch this amazing work of art, and I’m aware of the multiple meanings it can be given, from the characteristic sex obsession of many literary critics who see the mouth a vagina trying to give birth to the self (given that Whitelaw has a set of 32 immaculate-looking sharp teeth, these critics must have been hanging round some very odd vaginas); to the many invocations of philosophers and psychologists to extrapolate umpteen different theories of the self and not-self; through to the more purely literary notion that the endless repetition of the voice’s obsessive moments, insights, anxieties are a further iteration of the struggle of the narrator in The Unnamable to fulfil the compulsion, the order, the directive to talk talk talk he doesn’t know why, because he must, because they say so.

So I am aware of many types of interpretation the piece is susceptible to. But I also understand what Beckett meant when he said in an interview that:

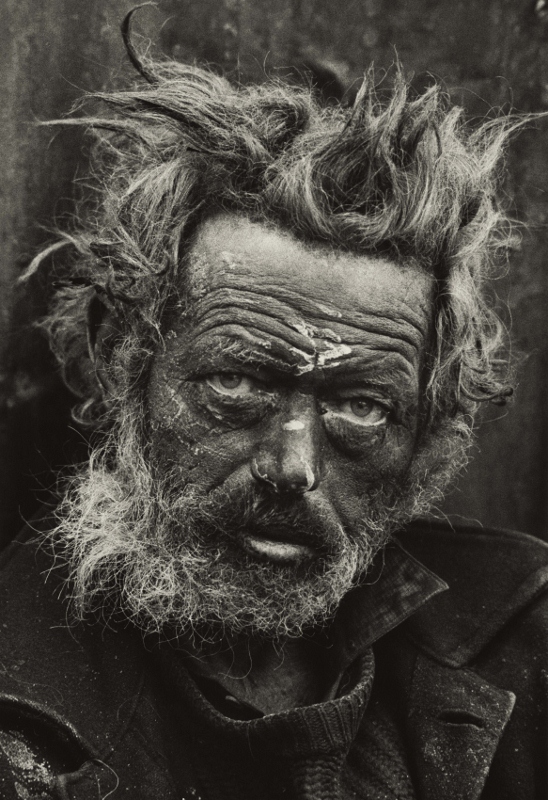

I knew that woman in Ireland. I knew who she was — not ‘she’ specifically, one single woman, but there were so many of those old crones, stumbling down the lanes, in the ditches, besides the hedgerows.

Because there were so many old, old ladies pottering across the road from the Priory or from other parts of my village, talking talking talking, babbling their way around the place in a continual stream of undertones and monologue, throughout my boyhood.

It is at the same time an artfully contrived work of avant-garde art, but also an unnervingly realistic depiction of how some people actually are. And not just some – nearly 9 million people in the UK are aged over 70, and Alzheimer’s disease has gone from being a condition few of us had heard about 20 years ago, to now being the leading cause of death in the UK.

Related link

Samuel Beckett’s works

An asterisk indicates that a work was included in the Beckett on Film project, which set out to make films of all 19 of Beckett’s stage plays using leading actors and directors. The set of 19 films was released in 2002 and most of them can be watched on YouTube.

- More Pricks Than Kicks (1934) Short stories

- Murphy (1938) Novel

The Second World War 1939 to 1945

- Watt (written 1945, pub.1953) Novel

- Mercier and Camier (1946) Novel

- First Love (1946) Short story

- The Expelled (1946) Short story

- The Calmative (1946) Short story

- The End (1946) Short story

- Molloy 1 (1951) Novel

- Molloy 2 (1951) Novel

- Malone Dies (1951) Novel

- The Unnamable (1953) Novel

*Waiting For Godot 1953 Play

- All That Fall (1957) Radio play

- *Acts Without Words I & II (1957) Mimes

- *Endgame (1958) Stage play

- *Krapp’s Last Tape (1958) Stage play

- *Rough for Theatre I & II – Stage plays

- Embers (1959) – Radio play

- The Old Tune (1960) adaptation of a radio play by French writer Robert Pinget

- *Happy Days (1961) – Stage play

- Rough for Radio I & II (1961) Radio plays

- Words and Music (1961) Radio play

- Cascando (1961) Radio play

- *Play (1963) Stage play

- Film (1963) Scenario for a film

- All Strange Away (1964) Short prose

- Imagination Dead Imagine (1965) Short prose

- How it Is (1964) Novel

- Enough (1965) Short prose

- Ping (1966) Short prose

- *Come and Go (1965) Stage play

- Eh Joe (1967) Television play

- *Breath (1969) Stage play

Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature 1969

- Lessness (1970) Short prose

- The Lost Ones (1966-70) Short prose

- *Not I (1972) Stage play

- Fizzles (1973 to 1975) Short prose pieces

- Heard in the Dark, One evening and others – Short prose pieces

- *That Time (1975) Stage play

- *Footfalls (1976) Stage play

- Ghost Trio (1976) Television play

- …but the clouds… (1977) Television play

- Company (1980) Novella

- *A Piece of Monologue (1980) Stage play (Beckett on Film production)

- *Rockaby (1981) Stage play

- Quad I + II (1981) Television play

- Ill Seen Ill Said (1981) Short novel

- *Ohio Impromptu (1981) Stage play

- *Catastrophe (1982) Stage play

- Worstward Ho (1983) Prose

- Nacht und Träume (1983) Television play

- *What Where (1983) Stage play

- Stirrings Still (1988) Short prose

- Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett by James Knowlson (1996) part 1

- Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett by James Knowlson (1996) part 2

- Samuel Beckett timeline