This exhibition opened last summer and was timed to coincide with the centenary of the end of the Great War (November 1918) and to complement the Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One exhibition at Tate Britain.

It consists of five rooms at Tate Modern which are hung with a glorious selection of the grotesque, horrifying, deformed and satirical images created by German artists during the hectic years of the Weimar Republic, which rose from the ashes of Germany’s defeat in the Great War, staggered through a series of crises (including when the French reoccupied the Rhineland industrial region in 1923 in response to Germany falling behind in its reparations, leading to complete economic collapse and the famous hyper-inflation when people carried vast piles of banknotes around in wheelbarrows), was stabilised by American loans in 1924, and then enjoyed five years of relative prosperity until the Wall Street crash of 1929 ushered in three years of mounting unemployment and street violence, which eventually helped bring Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party to power in January 1933, and fifteen years of hectic experimentation in all the arts ground to a halt.

The exhibition consists of around seventy paintings, drawings and prints, plus some books of contemporary photography. The core of the exhibition consists of pieces on loan from the George Economou Collection, a weird and wonderful cross-section of art from the period, some of which have never been seen in the UK before.

The exhibition has many surprises. For sure there are the images of crippled beggars in the street and pig-faced rich people in restaurants – images made familiar by the savage satire of Otto Dix (1891 to 1969) and George Grosz (1893 to 1959). And there are paintings of cabaret clubs and performers, including the obligatory transsexuals, cross-dressers, lesbians and other ‘transgressive’ types so beloved of art curators (a display case features a photo of ‘the Chinese female impersonator Mei Lanfang dressed as a Chinese goddess… alongside American Barbette.’)

But a lot less expected was the room devoted to religious painting in the Weimar Republic, which showed half a dozen big paintings by artists who struggled to express Christian iconography for a modern, dislocated age.

And the biggest room of all contains quite a few utterly ‘straight’ portraits of respectable looking people with all their clothes on done in a modern realistic style, alongside equally realistic depictions of houses and streetscapes.

The Great War

The First World War changed everything. In Germany, the intense spirituality of pre-war Expressionism no longer seem relevant, and painting moved towards realism of various types. This tendency towards realism, sometimes tinged with other elements – namely the grotesque and the satirical – prompted the art critic Franz Roh (1890 to 1965) to coin the expression ‘Magical Realism’ in 1925.

Magical Realism

Roh identified two distinct approaches in contemporary German art. On the one hand were ‘classical’ artists inclined towards recording everyday life through precise observation. An example is the painting of the acrobat Schulz by Albert Birkle (1900 to 1986). It epitomises several elements of magical realism, namely the almost caricature-like focus on clarity of line and definition, the realist interest in surface details, but also the underlying sense of the weird or strange (apparently, Schulz was famous for being able to pull all kinds of funny faces).

Roh distinguished the ‘classicists’ from another group he called the ‘verists’, who employed distorted and sometimes grotesque versions of representational art to address all kinds of social inequality and injustice.

Other critics were later to use the phrase New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) to refer to the same broad trend towards an underlying figurativeness.

Classicists and Verists

The exhibition gives plenty of examples of the striking contrast between the smooth, finished realism of the ‘classicists’ and the scratchy, harsh caricatures of the ‘verists’.

The first room is dominated by a series of drawings by the arch-satirists George Grosz and Otto Dix, the most vivid of which is the hectic red of Suicide, featuring the obligatory half-dressed prostitute and her despicable bourgeois client looking out onto a twisted, angular street where the eye is drawn to the figure sprawled in the centre (is it a blind person who has tripped over, or been run over?) so that it’s easy to miss the body hanging from a street lamp on the left which, presumably, gives the work its title.

You can, perhaps, detect from the painting that Grosz had had a complete nervous breakdown as a result of his experiences on the Western Front.

Room 1. The Circus

For some reason the circus attracted a variety of artists, maybe because it was an arena of fantasy and imagination, maybe because the performers were, by their nature, physically fit specimens (compared to the streets full of blind, halt, lame beggars maimed by the war), maybe because of its innocent fun.

Not that there’s anything innocent or fun about the ten or so Otto Dix prints on the subject on show here, with their rich array of distortions, contortion, crudeness and people who are half-performer, half-beast.

Room 2. From the visible to the invisible

This phrase, ‘from the visible to the invisible’, is taken from a letter in which the artist Max Beckmann (1884 to 1950) expressed his wish to depict the ‘idea’ which is hiding behind ‘reality’.

This sounds surprisingly like the kind of wishy-washy thing the Expressionists wrote about in 1905 or 1910, and the room contains some enormous garish oil paintings, one by Harry Heinrich Deierling which caught my eye. This is not at all what you associate with Weimar, cabaret and decadence. This work seemed to me to hark back more to Franz Marc and the bold, bright simplifications of Der Blaue Reiter school. And its rural setting brings out, by contrast, just how urban nearly all the other works on display are.

A bit more like the Weimar culture satire and suicide which we’re familiar with was a work like The Artist with Two Hanged Women by Rudolf Schlichter (1890 to 1955), a half-finished drawing in watercolour and graphite depicting, well, two hanged women. Note how the most care and attention has been lavished on the dead women’s lace-up boots. Ah, leather – fetishism – death.

Indeed dead women, and killing women, was a major theme of Weimar artists, so much so that it acquired a name of its own, Lustmord or sex murder.

The wall label points out that anti-hero of Alfred Döblin’s 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz has just been released from prison after murdering a prostitute. The heroine of G. W. Pabst’s black-and-white silent movie Pandora’s Box ends up being murdered (by Jack the Ripper). But you don’t need to go to other media to find stories of femicide. The art of the verists – the brutal satirists – is full of it.

The label suggests that all these images of women raped, stabbed and eviscerated were a reaction to ‘the emancipation of women’ which took place after the war.

This seems to me an altogether too shallow interpretation, as if these images were polite petitions or editorials in a conservative newspaper. Whereas they seem to me more like the most violent, disgusting images the artists could find to express their despair at the complete and utter collapse of all humane and civilised values brought about by the war.

The way women are bought, fucked and then brutally stabbed to death, their bodies ripped open in image after image, seems to me a deliberate spitting in the face of everything genteel, restrained and civilised about the Victorian and Edwardian society which had led an entire generation of young men into the holocaust of the trenches. Above all these images are angry, burning with anger, and I don’t think it’s at women getting the vote, I think it’s at the entire fabric of so-called civilised society which had been exposed as a brutal sham.

Room 3. On the street and in the studio

The hyper-inflation crisis of 1923 was stabilised by the implementation of the Dawes Plan in 1924, under which America lent Germany the money which it then paid to France as reparations for the cost of the war. For the next five years Germany enjoyed a golden period of relative prosperity, becoming widely known for its liberal (sexual) values and artistic creativity, not only in art but also photography, design and architecture (the Bauhaus).

The exhibition features a couple of display cases which show picture annuals from the time, such as Das Deutsches Lichtbild. The photo album was a popular format which collected together wonderful examples of the new, avant-garde, constructivist-style b&w photos of the time into a lavish and collectible book format.

And – despite pictures such as Deierling’s Gardener – it was an overwhelmingly urban culture. Berlin’s population doubled between 1910 and 1920, the bustling streets of four million people juxtaposing well-heeled bourgeoisie and legless beggars, perfumed aristocrats and raddled whores.

But alongside the famously scabrous images of satirists like Grosz and Dix, plenty of artists were attracted by the new look and feel of densely populated streets, and this room contains quite a few depictions of towns and cities, in a range of styles, from visionary to strictly realistic.

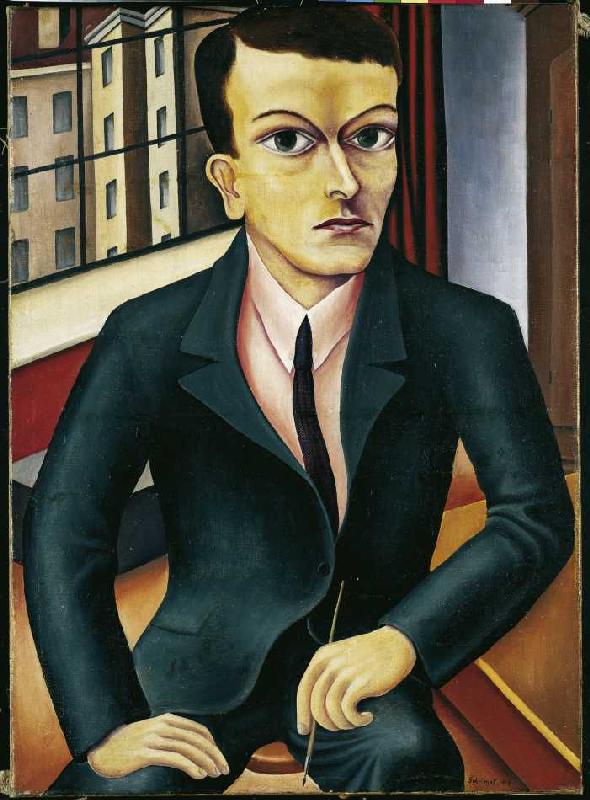

And of course there was always money to be made supplying the comfortably off with flattering portraits, and this room contains a selection of surprisingly staid and traditional portraits.

This is the kind of thing Roh had in mind when he wrote about the ‘classicists’, highlighting the tendency among many painters of the time towards minute attention to detail, and the complete, smooth finishing of the oil.

Room 4. The cabaret

Early 20th century cabaret was quite unlike the music halls which had dominated popular entertainment at the end of the 19th. Music hall catered to a large working class audience, emphasising spectacle and massed ranks of dancers or loud popular comedians. Cabaret, by contrast, took place in much smaller venues, often catering to expensive or elite audiences, providing knowingly ‘sophisticated’ performers designed to tickle the taste buds of their well-heeled clientele. The entertainment was more intimate, direct and often intellectual, mixing smart cocktail songs with deliberately ‘decadent’ displays of semi-naked women or cross-dressing men.

In fact there are, ironically, no paintings of an actual cabaret in the cabaret room, which seems a bit odd. The nearest thing we get is a big painting of the recently deceased Eric Satie (d.1925) in what might be a nightclub.

There are the picture books I mentioned above, featuring some famous cross-dressers of the time. And – what caught my eye most – a series of large cartoony illustrations of 1. two painted ladies 2. a woman at a shooting stall of a fair offering a gun to a customer 3. and a group of bored women standing in the doorway of a brothel.

These latter are the best things in the room and one of the highlights of the entire exhibition. Even though I recently read several books about Weimar art, I had never heard of Jeanne Mammen. Born in 1890, ‘her work is associated with the New Objectivity and Symbolism movements. She is best known for her depictions of strong, sensual women and Berlin city life.’ (Wikipedia) During the 1920s she contributed to fashion magazines and satirical journals and the wall label claims that:

Her observations of Berlin and its female inhabitants differ significantly from her male contemporaries. Her images give visual expression to female desire and to women’s experiences of city life.

Maybe. What I immediately responded to was the crispness and clarity of her cartoon style, closely related to George Grosz in its expressive use of line but nonetheless immediately distinctive. A quick surf of the internet shows that the three works on display here don’t really convey the distinctiveness of her feminine perspective as much as the wall label claims. I’m going to have to find out much more about her. She’s great.

Room 5. Faith and magic

In some ways it’s surprising that Christianity survived the First World War at all, until you grasp that its main purpose is to help people make sense of and survive tragedies and disasters. Once, years ago, I made a television programme about belief and atheism. One of the main themes which emerged was that all the atheists who poured scorn on religious belief had led charmed, middle-class lives which gave them the unconscious confidence that they could abolish the monarchy, have a revolution and ban Christianity because they knew that nothing much would change in their confident, affluent, well-educated lives.

Whereas the Christians I spoke to had almost all undergone real suffering – I remember one whose mother had been raped by her step-father, another who had lost a brother to cancer – one way or another they had had to cope with real pain in their lives. And their Christian faith wasn’t destroyed by these experiences; on the contrary, it was made stronger. Or (to be cynical) their need for faith had been made stronger.

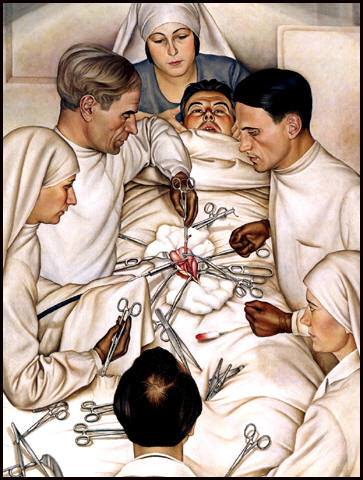

The highlights of this final room were two sets of large religious paintings by Albert Birkle and Herbert Gurschener.

From 1918 to 1919 there was an exhibition of Matthias Grunwald’s Isenheim altarpiece (1512) in Munich and this inspired Albert Birkle to tackle this most-traditional of Western subjects, but filtered through the harsh, cartoon-like grotesqueness of a Weimar sensibility. He was only 21 when he painted his version of the crucifixion and still fresh from the horrors of the Western Front. Is there actually any redemption at all going on in this picture, or is it just a scene of grotesque torture? You decide.

Herbert Gurschener (1901 to 1975) took his inspiration from the Italian Renaissance in paintings like the Triumph of Death, Lazarus (The Workers) and Annunciation. His Annunciation contains all the traditional religious symbolism, down to the stalk of white lilies, along with a form of post-Renaissance perspective. And yet is very obviously refracted through an entirely 20th century sensibility.

Thoughts

There is more variety in this exhibition than I’ve indicated. There are many more ‘traditional’ portraits in all of the rooms, plus a variety of townscapes which vary from grim depictions of urban slums brooding beneath factory chimneys to genuinely magical, fantasy-like depictions of brightly coloured fairy streets.

There is more strangeness and quirkiness than I’d expected, more little gems which are not easy to categorise but which hold the eye. It’s worth registering the loud, crude angry satire of Grosz and Dix, but then going back round to appreciate the subtler virtues of many of the quieter pictures, as well as the inclusions of works by ‘outriders’ like Chagall and de Chirico who were neither German nor painting during the post-war period. Little gems and surprises.

And the whole thing is FREE. Go see it before it closes in July.

Full list of paintings

This is a list of most of the paintings in the exhibition, though I don’t think it’s quite complete. Anyway, I give it here in case you want to look up more examples of each artist’s works.

Introduction

- Marc Chagall, The Green Donkey, 1911

- Giorgio de Chirico, The Duo, 1914

- Otto Dix, Portrait of Bruno Alexander Roscher, 1915

- George Grosz, Suicide, 1916

- Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, The Poet Däubler, 1917

- Carlo Mense, Self Portrait, 1918

- Heinrich Campendonk, The Rider II, 1919

- Henry Heinrich Dierling, The Gardner, 1920

- Max Beckman, Frau Ullstein (Portrait of a Woman), 1920

- Otto Dix Beautiful Mally! 1920

- Otto Dix Circus Scene (Riding Act) 1920

- Otto Dix Zirkus, 1922

- Otto Dix Performers 1922

- Paul Klee They’re Biting 1920, Comedy 1921

- Albert Birkle The Acrobat Schulz V, 1921

- George Grosz Drawing for ‘The Mirror of the Bourgeoisie’ 1925

- George Grosz Self-Portrait with Model in the Studio 1930 to 1937

- George Grosz A Married Couple 1930

From the visible to the invisible

- Otto Dix Butcher Shop 1920

- Otto Dix Billiard Players 1920

- Otto Dix Sailor and Girl 1920

- Otto Dix Lust Murderer 1920

- Otto Dix Lust Murderer 1922

- Rudolf Schlichter The Artist with Two Hanged Women 1924

- Christian Schad Prof Holzmeister 1926

The Street and the Studio

- Richard Biringer, Krupp Works, Engers am Rheim, 1925

- Albert Birkle, Passou, 1925

- Rudolf Dischinger, Backyard Balcony, 1935

- Conrad Felix Műller, Portrait of Ernst Buchholz, 1921

- Conrad Felix Műller, The Beggar of Prachatice, 1924

- Carl Grossberg, Rokin Street, Amsterdam, 1925

- Hans Grundig, Girl with Pink Hat, 1925

- Herbert Gurschner, Japanese Lady, 1932

- Herbert Gurschner, Bean Ingram, 1928

- Karl Otto Hy, Anna, 1932

- August Heitmüller, Self-Portrait, 1926

- Alexander Kanoldt, Monstery Chapel of Säben, 1920

- Josef Mangold, Flower Still Life with Playing Card, undated

- Nicolai Wassilief, Interior, 1923

- Carlo Mense, Portrait of Don Domenico, 1924

- Richard Müller, At the Studio, 1926

- Franz Radziwill, Conversation about a Paragraph, 1929

- Otto Rudolf Schatz, Moon Women, 1930

- Rudolf Schlichter, Lady with Red Scarf, 1933

- Marie-Louise von Motesicky, Portrait of a Russian Student, 1927

- Josef Scharl, Conference/The Group, 1927

- Werner Schramm, Portrait of a Lady in front of the Pont des Artes, 1930

The Cabaret

- Josef Ebertz, Dancer (Beatrice Mariagraete), 1923

- Otto Griebel, Two Women, 1924

- Prosper de Troyer, Eric Satie (The Prelude), 1925

- Sergius Pauser, Self-Portrait with Mask, 1926

- Jeanne Mammen, Boring Dolls, 1927

- Jeanne Mammen, At the Shooting Gallery, 1929

- Jeanne Mammen, Brüderstrasse (Free Room), 1930

- Max Beckmann, Anni (Girl with Fan), 1942

Faith

- Albert Birkle, Crucifixion, 1921

- Albert Birkle, The Hermit, 1921

- Herbert Gurschener, the Triumph of Death, 1927

- Herbert Gurschener, Lazarus (The Workers), 1928

- Herbert Gurschener, Annuciation, 1929 to 1930

Related links

- Magic Realism Art in Weimar Germany: 1919 to 1933 continues at Tate Modern until 9 June 2019

- The George Economou Collection website

Reviews relating to Germany

Art and culture

- Magic Realism Art in Weimar Germany: 1919 to 1933 @ Tate Modern (April 2019)

- Anni Albers @ Tate Modern (December 2018)

- Aftermath: Art in the wake of World War One @ Tate Britain (September 2018)

- Bauhaus: Art as Life @ the Barbican (July 2012)

- The New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic 1918 to 1933 edited by Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann (2015)

- The New Objectivity, some notes

- From Weimar to Wall Street 1918 to 1929 (1993)

- The Weimar Years: A Culture Cut Short by John Willett (1984)

- Bauhaus by Frank Whitford (1984)

- The New Sobriety: Art and Politics in the Weimar Period 1917 to 1933 by John Willett (1978)

- Weimar: A Cultural History 1918 to 1933 by Walter Laqueur (1974)

- Weimar Culture by Peter Gay (1968)

- A Small Yes and a Big No by George Grosz (1946)

History

- The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End 1917 to 1923 by Robert Gerwarth (2016)

- Ring of Steel by Alexander Watson (2014) A synopsis

- Bismarck: The Iron Chancellor by Volker Ullrich (2008)