This is a lovely exhibition of the popular, accessible and inspiring artist Anne Desmet – imaginative, decorative, beautiful to look at, civilised, teasingly clever and FREE.

From the website and the press release I hadn’t really grasped the scale of the exhibition. With over 150 works this is a major retrospective, which features series of works from as far back as 1990 right up to the present day, including 41 London-themed kaleidoscopic prints created exclusively for this new exhibition.

1. Wood carver par excellence

Born in 1964, Anne Desmet is a well-established artist and member of the Royal Academy who specializes in wood engravings, linocuts and mixed-media collages.

Desmet is a highly skilled carver in wood and creator of dazzling woodcuts. She is only the third artist to be elected to the RA for working in the medium of wood engraving. The exhibition includes a fascinating 6-minute film shot at her studio in Hackney which follows the entire process through, from starting with an endpiece bit of wood, then showing the various sharp carving tools she used to get her effects, through to rolling the print ink flat, inking the cut and then making the print.

There are also four display cases showing the raw wood piece, the tools she uses, the final engraved wood blocks, her notebooks, sketches and so on.

Display case in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery, showing, from left to right, a sketchbook, a virgin block of end-grain wood with some of her carving tools, and a finished engraving block (photo by the author)

Most of these woodcuts are in black and white. Some are coloured in but colour isn’t her thing: shapes and patterns are her thing. She can do astonishingly realistic depictions of Italian or London landmarks, gardens and buildings, but its the way she then mashes up these images which get her juices flowing (see below).

2. Architecture

Desmet is strongly attracted by architecture and in particular architecture with strong mathematical lines and geometric shapes. There are three rooms and the first one contains cityscapes and townscapes, depictions of Rome, rooftops of Italian provincial towns, scenes from Oxford (the Radcliffe Camera, Balliol College) and, in a surprise, a piece I really liked, a fantasia of Tudor chimney stacks as she observed them when she was, believe it or not, artist in residence in Eton, in 2016.

3. Fantasias

As you can tell from the Eton picture, this is a fantasia made up of lots of chimneys combined together into an improbably dense and overloaded image. She does the same to her Oxford landmarks, moving beyond the obvious aesthetic appeal of the colleges and instead creating fantastical images of, for example, the Radcliffe Camera, whose mighty dome appears ten or more times in a mashed-up fantastical image.

These clear crisp but fantastical images reminded me a little of the woodcut covers Scottish artist and novelist Alisdair Gray made for the covers of his books and short stories and John Lawrence’s illustrations for some of Philip Pullman’s fantasy stories, also set in Oxford. Also, the most fantastical of them are strongly redolent of Maurits Escher‘s optical illusions.

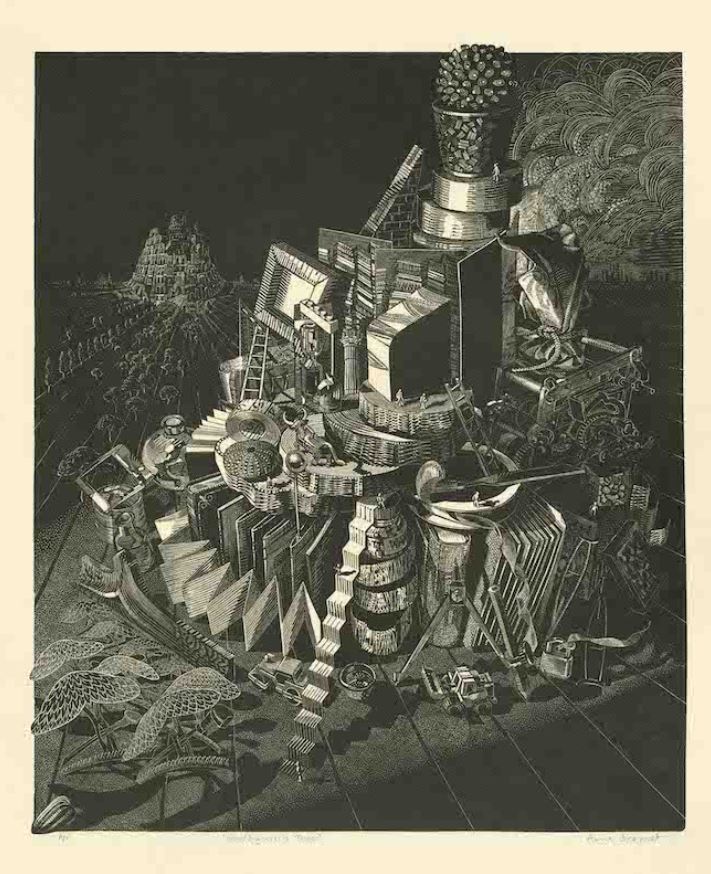

There are a handful of works from the 1990s which are completely fantastical, showing piles of household bric-a-brac (scissors, tape measure) mingled with learned tools such as you might find in a 17th century engraving depicting science (protractors and compass), with the image of Peter Breughel’s version of the Tower of Babel in the background and, snuffling in the foreground, miniature bulldozers and tiny people.

This image, Breughel’s tower, recurs throughout all of her work, sometimes centre stage, sometimes cropping up as an unexpected detail. It speaks to her interest in architecture, in large buildings, but also to the passage of time, and inevitable decay and collapse. Decline and fall. Ruined cities, empty streets, abandoned buildings…

My favourites in the first room were a series of images made by cutting up original prints and remaking them as collages. In particular I liked this one which takes is inspiration from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s story, ‘The Little Prince’, which I liked for its sci fi vibe but mainly for its shape and design and feel. Note the tiny photo of the Radcliffe Camera floating incongruously at the top right.

4. Mashing

So far so fairly realistic and there’s ample evidence that Desmet she can do breath-takingly realistic renderings of buildings and views. But the central concept is that Desmet chops up her work. It is sliced and diced, filleted, repeated, duplicated and recombined in a myriad ways, and it’s these processes which create her really stunning works. I made a list of the treatments she subjects her works to:

- basic realistic engraving

- fantasias – Tower of Babel, Eton chimneys, multiplying Radcliffe Cameras

- collages

- the same scene with variations – Urban Development or St Paul’s

- mounted on razor shells – cityscapes, Olympic buildings

- mounted on squares – Olympic Site A to Z

- mounted on slate – Perimeter Fence

- tall images – the angel tower

- sliced as by a paper shredder – the British Museum Grand Court sliced vertically, horizontally and diagonally

- hangings – British Museum

- cut-out illuminated by an LED light – St Paul’s

- behind glass cubes

- behind convex clock glass circle

- on crockery fragments – angels

- kaleidoscope

Kaleidoscope

The technique central to maybe half of these works is the simple but surprisingly effective technique of using a kaleidoscope.

The exhibition quote Desmet’s own explanation, which I’ll quote in full:

‘Many of the collages were made in 2022 while I was undergoing treatment for breast cancer and consequently, they reflect something of a wild scattergun of thoughts that were running through my mind at that time, such as escape, possible new worlds, and the climate crisis.

‘The framework for those thoughts was inspired by a kaleidoscope toy that I had bought at the Sir John Soane’s Museum some years ago, which breaks up whatever view you’re looking at into extraordinary triangulated repeat-patterns.

‘I set about applying a kaleidoscope lens to my London imagery to create new work for the exhibition at Guildhall Art Gallery. By seeing the city anew and with a sense of its unexpected possibilities, I hope that my work will inspire optimism and constructive thinking in our uncertain times.’

Sky Windows

And so she set about reviewing prints from her earlier wood-engravings, linocuts and hand-drawn lithographs, and kaleidoscoping them. The most comprehensive example is the piece titled ‘RA: Sky Window’. In 2017 the Royal Academy was undergoing a refurbishment and Desmet made some beautifully realistic paintings of the building.

Then, as explained, in 2023, she returned to the image armed with her kaleidoscope and realised that she could manipulate the skyline of the building so as to place the blue of the sky at the centre of a surprising variety of shapes.

Installation view of ‘Sky Windows’ by Anne Desmet (2023) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

And then she realised the blue sky could itself be changed to reflect, among other things, the changing seasons. And so she made versions featuring, for example, fireworks, snowflakes, pumpkins and so on, and the thought, why stop there? Why not be frivolous and whimsical, so there are ones with a rainbow, hot air balloons and helicopters, airplanes high in the sky leaving vapour trails. Suddenly you realise how much goes on in the sky above us without our really noticing.

‘Sky Window 23: Stars and Satellites’ by Anne Desmet (2023) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

There are 24 in total, building up into a beguiling, entrancing series. I realised it’s much like the idea of a theme and variations, a stock genre of classical music: first state the theme, then work through a host of inventive variations (Beethoven’s Diabelli variations. Elgar’s Enigma variations spring to mind).

So self-contained and neat is the idea and the execution that a) the entire series of 24 is assigned a room of its own off to the side of the main gallery and b) you can buy the box set!

Installation view of the Sky Windows box set in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

London Gardens

She does the same thing but with a different visual result in a series called ‘London Kaleidoscope’. Here she starts with totally realistic (and wonderfully vivid and detailed) engravings of a) a London garden, in fact the view from her house and b) a pub down the road with a red phone box outside.

She collages the original prints, to include the red phone box and greenery from the garden, and then takes her kaleidoscope to the original works and comes up with a (small) set of really vivid, beautiful images, arguably the best in the exhibition. They are London but seen in an entirely new, novel, fun and beautiful way.

‘London Gardens Kaleidoscope 1’ by Anne Desmet (2023) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

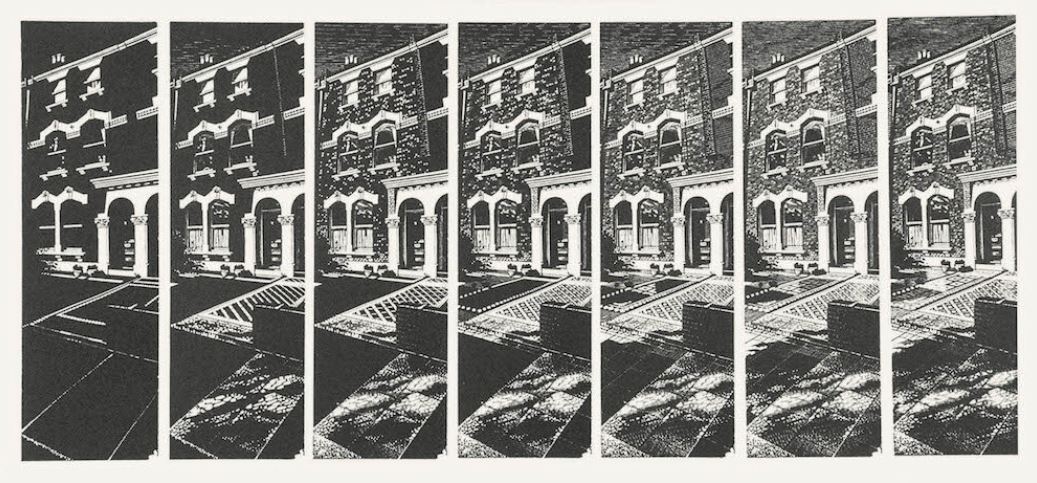

The same scene with variations

Depicting a scene over time. Thus one of my favourites, the lovely ‘Urban Development’, depicts the front of a London house at seven times of day, showing the sun rising and its light slowly revealing more and more details of the scene.

‘Urban Development’ by Anne Desmet (2023) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

Mounted on razor shells

There are at least three pieces which consist images of buildings carefully cut out and stuck onto razor shells. These are all exquisite and the fragility of the process and the end result gives you a fantastic sense of fragility and delicacy.

Installation view of ‘Fragile Earth’ by Anne Desmet (2022) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery

In this piece fragments from prints she’s made of London, Rome, New York, Venice are collaged to produce an international skyline with the natural pink/purple colouring of the shells giving the sense of sunset over this megalopolis.

As good or better is the smaller series made using images she drew, carved and printed of the build-up to the London Olympics in 2012. Here is a finely detailed view of the Olympic velodrome cut up and pasted onto six razor shells. Amazingly powerful, the exquisite detailing of the original image then cut up onto these very fragile artefacts from a fragile, damaged natural world.

‘Fragile Hope’ by Anne Desmet (2012) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

The third razor shell work is ‘Fires of London’, created using 18 razor-clam shells to dramatise the many historic fires of London over the last 1,500 years. The work has just been acquired for the Guildhall’s permanent collection.

‘Fires of London’ by Anne Desmet (2012) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

Mounted on squares

There’s some example of another type of mounting, chopping an image up into small, mounted squares. In this example a wood engraving of the Olympic site is collaged / mixed into the relevant A to Z map of the same location, and then diced up into 75 small squares.

I love collage, pieces and fragments and, because I live in London, the A to Z map has an additional frisson or connotation. It is also a fairly obvious meditation on the dichotomy between map and world, which always fascinated me.

Towers

A number of the works are tall and narrow, mimicking the tall chimneys or towers she’s interested in – I’ve shown the Eton chimneys, above. There’s a similar series showing a ‘tower of angels’.

The angel tower is one of a set of works inspired by Victorian bas-relief decorative angel sculptures near the ceiling in the Royal Academy’s Gallery 3. She created individual prints, this tower, and a work in ceramics (see below). The theme of angels (sometimes used as a nickname for nurses) seemed appropriate when she was making them, during the first year of the pandemic lockdown. You can tell these are more modern works because they have more edge. In particular, in some of the works the angels are wearing protective face masks. COVID art.

‘Triptych for Our Times’ by Anne Desmet (2020) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

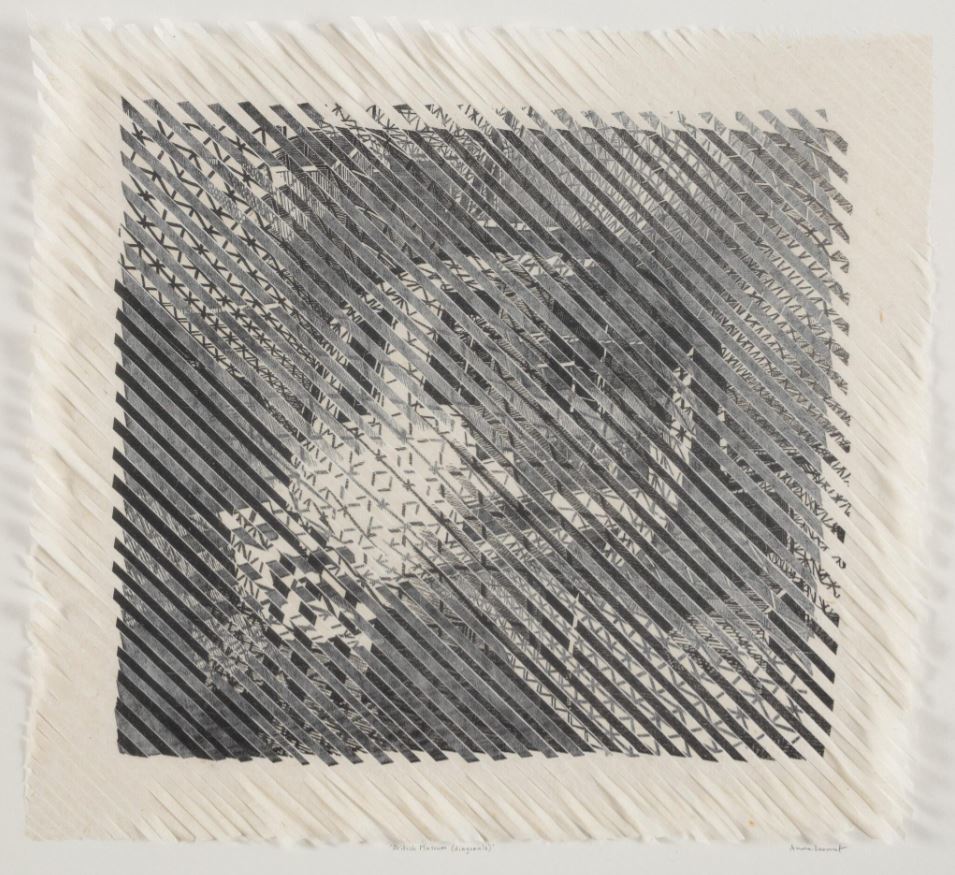

Sliced as by a paper shredder

She feeds versions of her lovely print of the British Museum Grand Court through a shredder. One sliced vertically, one horizontally, one diagonally. This image doesn’t do it justice. Only in the flesh can you see the fineness of the very thin paper shreds, curling slightly at the corners, which convey a powerful sense of evanescent fragility, a continuous theme throughout her work.

‘British Museum Diagonals’ by Anne Desmet (2005) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery

Mounted on slate

This was another of my favourites. Only 2 or 3 of the works were mounted on slate but it’s a powerful material and it seemed, to me, strongly appropriate for the subject. It’s a depiction, a dramatisation, of the forbidding metal fences erected all around the Olympic site in East London in the years while it was being built.

‘Perimeter fence’ by Anne Desmet (2012) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

I went for a walk around the area during that time and was intimidated, indeed slightly scared, and irked, by the way these ‘games for the people’ involved shutting off vast areas which had previously been free to roam, for years and years. In this piece the shredding technique a) re-enacts the look of the vertical metal fences b) enacts the way you could only glimpse fragments of what was going on on the sites through the slats and c) the slate mounting conveys the adamantine, hard, take-no-prisoners high security vibe which was imposed across the whole area.

Hangings

Closely related are a couple of hangings applying the kaleidoscope technique to the British Museum Grand Court image, rearranging details into immensely pleasing geometric patterns. From a distance they look like abstract geometric shapes but when you go up close you can see the architectural details of the Museum walls and ceiling. Magical!

Two hangings by Anne Desmet (2012) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

Cutout illuminated by an LED light

There’s a series of six pictures of St Paul’s cathedral, taken from the identical same sport but showing it at different times of night, and in history, so with some scenes depicting the Blitz, enemy planes overhead and searchlights.

One of these has been reworked so the white parts of the image are made translucent (by a laser, apparently) and has been attached to an LED light box so as to create a little son-et-lumiere. To be honest, this felt a bit gimmicky and was one of the very few pieces which didn’t work for me.

Behind glass cubes

Like one of her engravings of the Olympic velodrome, cut into squares and smoothly rounded glass cubes set over each square.

Interesting experiment but a bit self-defeating as it was hard if not impossible to make out the original image, which explains why it only occurs once.

Behind a convex clock glass circle

Speaking of glass, another image manipulation she’s experimented with is placing a collage or print behind a convex glass circle such as you find on the front of old grandfather clocks. An interesting idea but, in my opinion, this blunted your reading of her finely drawn, detailed images, working against her strengths and so this was the one format which didn’t really light my candle. This flat photo of one doesn’t at all convey the shiny bulbous effect of the work.

The curators point out how the use of convex glass, as used in old-style clocks, strongly references the notion of Time, linking up with the passage of time indicated, in different ways, by other series (St Paul’s at night; Sky Windows; Urban development and so on). So a clever-clever idea, but I don’t think works in practice, as actual artefacts.

On crockery fragments

On the other hand, I love fragments, wrecks and ruins, bits of industrial detritus, which is why I love the Arte Povera movement, minimalism, the wonderful photos of Jane and Louise Wilson, the great Cornelia Parker and so on. And so I loved the handful of places where she’s laminated her lovely images into fragments of crockery, as with this striking dismantling of one of the angel images.

‘Angel Fragment 2’ by Anne Desmet (2021) in ‘Kaleidoscope/London’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (photo by the author)

Again, this speaks to the recurrent them in her work of large buildings or neo-classical architecture or Victorian art (as here) degraded, broken, fragmented by the passage of time.

Thoughts

Delightful, inspiring, endlessly inventive, beautiful images and, in the shape of the video and the display cases, very informative about the craft of wood engraving. And it’s FREE. Go and see it.

Related links

- Anne Desmet: Kaleidoscope/London Exhibition continues at the Guildhall Art Gallery until 8 September 2024

- Anne Desmet website

- Catalogue of a comprehensive exhibition at Abbott and Holder, featuring scores of images