One of the most dazzling, mind-boggling and genuinely gripping novels I’ve ever read.

The story is set in the future, after the customary nuclear war which happens in so many futurestories. The twist on this one is that, after the radiation died down, the world’s powers agreed under something referred to as ‘the Covenant’ to put Sweden in charge, handing over all nuclear devices to a country big enough to manage them and keep the peace, but small enough not to have any global ambitions of her own.

Thus liberated from war, humanity – again, as in so many of these optimistic futurestories from the 1950s and 60s – has focused its efforts on space exploration using the handy new ‘ion drive’ which has been discovered, along with something called ‘Bussard engines’, helped along by elaborate ‘scoopfield webs’ to create ‘magnetohydrodynamic fields’.

Reaction mass entered the fire chamber. Thermonuclear generators energised the furious electric arcs that stripped those atoms down to ions; the magnetic fields that separated positive and negative particles; the forces that focused them into beams; the pulses that lashed them to ever higher velocities as they sped down the rings of the thrust tubes, until they emerged scarcely less fast than light itself.

The idea is that the webs are extended ‘nets’ a kilometre or so wide, which drag in all the hydrogen atoms which exist in low density in space, charging and channeling them towards the ‘drive’ which strips them to ions and thrusts them fiercely out the back of the ship – hence driving it forward.

Several voyages of exploration have already been undertaken to the nearest star systems in space ships which use these drives to travel near the speed of light, and fast-moving ‘probes’ have been sent to all the nearest star systems.

One of these probes reached the star system Centauri and now, acting on its information, a large spaceship, the Leonora Christine, is taking off on a journey to see if the third planet orbiting round Centauri really is habitable, as the probe suggests, and could be settled by ‘man’.

Einstein’s theory of relativity suggests that as any object approaches the speed of light, its experience of time slows down. The plan is for the Leonora Christine to accelerate for a couple of years towards near light speed, travel at that speed for a year, then slow down for a couple of years.

Five years there, whereupon they will either a) stay if the planet is habitable b) return, if it is not. Due to this time dilation effect those on the expedition will only age twelve years or so, while 43 or more years will pass back on earth (p.49).

(Time dilation is a key feature of Joe Haldeman’s novel, The Forever War, in which the protagonist keeps returning from tours of duty off-world to discover major changes in terrestrial society have taken place in his absence: it is, therefore, a form of one-way time travel.)

The Leonora Christine carries no fewer than fifty passengers, a cross-section of scientists, engineers, biologists and so on. Unlike any other spaceship I’ve read of it is large enough to house a gym, a theatre, a canteen and a swimming pool!

Two strands

Tau Zero is made up of two very different types of discourse. It is (apparently) a classic of ‘hard’ sci fi because not three pages go by without Anderson explaining in daunting technical detail the process workings of the ion drive, or the scoopnets, explaining the ratio of hydrogen atoms in space, or how the theory of relativity works, and so on. Not only are there sizeable chunks of uncompromising scientific information every few pages, but understanding them is key to the plot and narrative.

Starlike burned the hydrogen fusion, aft of the Bussard module that focused the electromagnetism which contained it. A titanic gas-laser effect aimed photons themselves in a beam whose reaction pushed the ship forward – and which would have vaporised any solid body it struck. The process was not 100 percent efficient. But most of the stray energy went to ionise the hydrogen which escaped nuclear combustion. These protons and electrons, together with the fusion products, were also hurled backward by the force fields, a gale of plasma adding its own increment of momentum. (p.40)

But at the same time, or regularly interspersed with the tech passages, are the passages describing the ‘human interest’ side of the journey, which is full of clichés and stereotypes, a kind of Peyton Place in space. To be more specific, the book was first published in instalments in 1967 and it has a very 1960s mindset. Anderson projects idealistic 1960s talk about ‘free love’ into a future in which adults have no moral qualms about ‘sleeping around’.

Before they leave, the novel opens with a pair of characters in a garden in Stockholm walking and having dinner and then the woman, Ingrid Lindgren, proposes to the man, Charles Reymont, that they become a couple. During all the adventures that follow, there is a continual exchanging of partners among the 25 men and 25 women on board, with little passages set aside for flirtations and guytalk about the girls or womentalk about the boys.

When a partnership ends one of the couple moves out, the other moves in with a room-mate of the same sex for a period, or immediately moves in with their new partner. It’s like wife-swapping in space. In a key moment of the plot, the ship’s resident astronomer, a short ugly anti-social and smelly man, becomes so depressed that he can no longer function. At which point Ingrid tactfully gets rid of the concerned captain and officers and… sleeps with him. So sex is deployed ‘tactically’ as a form of therapy.

Sex

He admired the sight of her. Unclad, she could never be called boyish. The curves of her breasts and flank were subtler than ordinary, but they were integral with the rest of her – not stuccoed on, as with too many women – and when she moved, they flowed. So did the light along her skin which had the hue of the hills around San Francisco Bay in their summer, and the light in her hair, which had the smell of every summer day that ever was on earth. (p.62)

Feminism

From a feminist perspective, it is striking how the 25 women aboard the ship are a) all scientists and experts in their fields b) are not passive sex objects, but very active in deciding who they want to partner with and why. One of the two strong characters in the narrative is a woman, Ingred Lindgren.

Characters

- Captain Lars Telander

- Ingrid Lindgren, steely disciplined first officer

- Charles Reymont, takes over command when the ship hits crisis

- Boris Fedoroff, Chief Engineer

- Norbert Williams, American chemist

- Chi-Yuen Ai-Ling, Planetologist

- Emma Glassgold, molecular biologist

- Jane Sadler, Canadian bio-technician

- Machinist Johann Freiwald

- Astronomer Elof Nilsson

- Navigation Officer, Auguste Boudreau

- Biosystems Chief Pereira

- Margarita Jimenes

- Iwamoto Tetsuo

- Hussein Sadek

- Yeshu ben-Zvi

- Mohandas Chidambaran

- Phra Takh

- Kato M’Botu

Thus the ship’s progress proceeds smoothly, while the crew discuss decorating the canteen and common rooms, paint murals and have numerous affairs. Five years is a long time to pass in a confined ship. And meanwhile the effects of travelling ever closer to light speed create unusual effects and, to be honest, I was wondering what all the fuss was about this book.

When Leonora Christine attained a substantial fraction of light speed, its optical effects became clear to the unaided sight. Her velocity and that of the rays from a star added vectorially; the result was aberration. Except for whatever lay dead aft or ahead, the apparent position changed. Constellations grew lopsided, grew grotesque, and melted, as their members crawled across the dark. More and more, the stars thinned out behind the ship and crowded before her. (p.45)

Tau

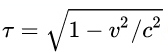

Anderson gives us a couple of pages introducing the tau equation. This defines the ‘interdependence of space, time, matter, and energy’, If v is the velocity of the spaceship, and c the velocity of light, then tau equals the square root of 1 minus v² divided by c². In other words the closer the ship’s velocity, v, gets to the speed of light, c (186,00 miles per second), then v² divided by c² gets closer and closer to 1; therefore 1 minus something which is getting closer to 1 gets closer and closer to 0; and the square root of that number similarly approaches closer and closer to zero.

Or to put it another way, the closer tau gets to zero the faster the ship is flying, the greater its mass, and the slower the people inside it experience time, relative to the rest of the ‘static’ universe.

The plot kicks in

So the narrative trundles amiably along for the first 60 or so pages, interspersing passages of dauntingly technical exposition with the petty jealousies, love affairs and squabbles of the human characters, until…

The ship passes through an unanticipated gas cloud, just solid enough to possibly destroy her, at the very least do damage – due to the enormous speed she’s now flying at which effects her mass.

Captain Telander listens to his experts feverishly calculating what impact will mean but ultimately they have to batten down the hatches, make themselves secure and hope for the best, impact happening on page 75 of this 190-page long book.

In the event the ship survives but the technicians quickly discover that impact has knocked out the decelerating engines. Now, much worse, the technicians explain to the captain and the lead officers, First Officer Lindgren and the man responsible for crew discipline, Reymont, the terrible catch-22 they’re stuck in.

In order to investigate what’s happened to the decellerator engines, the technicians would have to go to the rear of the ship and investigate manually. Unfortunately, they would be vaporised in nano-seconds by the super-powerful ion drive if they got anywhere near it. Therefore, no-one can investigate what’s wrong with the decelerator engine until the accelerator engine is turned off.

But here’s the catch: the ship is travelling so close to the speed of light that, if they turned the accelerator engines off, the crew would all be killed in moments. Why? Because the ship is constantly being bombarded by hydrogen atoms found in small amounts throughout space. At the moment the accelerator engines and scoopfield webs are directing these atoms away from the ship and down into the ion drive. The ion drive protects the ship. The moment it is turned off, these hydrogen atoms will suddenly be bombarding the ship’s hull and, because of the speed it is going at, the effect will be to split the hydrogen atoms releasing gamma rays. The gamma rays will penetrate the hull and fry all the humans inside in moments.

Thus they cannot stop. They are doomed to continue accelerating forever or until they all die.

It is at this point that the way Anderson has introduced us to quite a few named characters, and shown them bickering, explaining abstruse theory, getting drunk and getting laid begins to show its benefits. Because the rest of the novel consists of a series of revelations about the logical implications of their plight and, if these were just explained in tech speak they would be pretty flat and dull: the drama, the grip of the novel derives from the way the matrix of characters he’s developed respond to each new revelation: getting drunk, feeling suicidal, determined to tough it out, relationships fall apart, new relationships are formed. In and of themselves these human interest passages are hardly Tolstoy, but they are vital for the novel’s success because they dramatise each new twist in the story and, as the characters discuss the implications, the time spent reading their dialogue and thoughts helps the reader, also, to process and assimilate the story’s mind-blowing logic.

A series of unfortunate incidents

Basically what happens is there is a series of four or five further revelations which confirm the astronauts in their plight, but expand it beyond their, or our, wildest imaginings.

At first the captain and engineer come up with a plan of sorts. They know, or suspect, that between galaxies the density of hydrogen atoms in the ether falls off. If they can motor beyond our galaxy they can find a place where the hydrogen density of space is so minute that they can afford to turn off the ion drive and repair the decelerator.

This is discussed in detail, with dialogue working through both the technical aspects and also the emotional consequences. Many of the crew had anticipated returning to earth to be reunited with at least some members of their family. Now that has gone for good. As has the original plan of exploring an earth-style planet.

And so we are given some mind-blowing descriptions of the ship deliberately accelerating in order to pass right through the galaxy and beyond. But unfortunately, the scientists then discover that the space between galaxies is not thin enough to protect them. Also there is another catch-22. In order to travel out of the galaxy they have had to increase speed. But now they are flying everso close to the speed of light, the risk posed by turning off the ion drive and exposing themselves to the stray hydrogen atoms in space has become greater. The faster they go in order to find space thin enough to stop in, the thinner that space has to become.

The astronomers now come to the conclusion that space is still to full of hydrogen atoms in the sectors which contain clusters of galaxies. They decide to increase the ship’s velocity even more in order not just to leave our galaxy, but to get clear of our entire family of galaxies. This they calculate, will take another year or so at present velocities.

Thus it is that the book moves forward by presenting a new problem, the scientists suggest a solution which involves travelling faster and further, the crew is told and slowly gets used to the idea, as do we, via various conversations and attitudes and emotional responses. But when that goal is attained, it turns out there is another problem, and so the tension and the narrative drive of the book is relentlessly ratcheted up.

And of course, the further they travel and the closer to light speed, the more the tau effect predicts that time slows down for them, or, to put it another way, time speeds up for the rest of the universe. Early on in the post-disaster section, the crew assemble to celebrate the fact that a hundred years have passed back on earth: everyone they knew is dead. It is a sombre assembly with heavy drinking, casual sex, melancholy thoughts.

But by the time we get to the bit where they have flown clear of the galaxy only to be disappointed to find that inter-galactic space is too full of hydrogen for them to stop, by this stage they realise that thousands of years have passed back on earth.

By the time they fly free of the entire cluster of galaxies, they know that tens of thousands of years have passed. And eventually, as their tau approaches closer and closer to zero, they realise that millions of years have passed (one million is passed n page 136).

For when they do eventually fly beyond our entire family of galaxies they encounter another problem which is discovering that empty space is now too dispersed to allow them to decelerate. Even if they turn off the ion drive and fix the decelerating engine, there isn’t enough matter in truly empty space for the engine to latch on to and use as fuel to slow them (p.147).

Thus they decide to continue onwards, letting their acceleration, and mass, increase until they find a part of space with just the right conditions.

The accessible mass of the whole galactic clan that was her goal proved inadequate to brake her velocity. Therefore she did not try. Instead, she used what she swallowed to drive forward all the faster. She traversed the domain of this second clan – with no attempt at manual control, simply spearing through a number of its member galaxies – in two days. On the far side, again into hollow space, she fell free. The stretch to the next attainable clan was on the order of another hundred million light-years. She made the passage in about a week. (p.151)

On they fly at incomprehensible speed, while various human interest stories unfurl between the ship’s crew, until they (and the reader) reach the blasé condition of feeling the ship’s hull rattle and hum for a few moments and a character will say, ‘There goes another galaxy’.

Now if this was a J.G. Ballard novel, they’d all have gone mad and started eating each other by now. Anderson’s take on human psychology is much more bland and optimistic. Some of the crew get a bit depressed, but nothing some casual sex, or a project to redecorate the canteen can’t fix.

The main ‘human’ part of the narrative describes the way the ship’s ‘constable’, Charles Reymont who we met back on the opening pages, takes effective control from the captain. Initially this is basic psychology, Charles realising it will help discipline best if the captain becomes an aloof figure beyond criticism or reproach while he, Charles, imposes discipline, structure and purpose – allotting the crew tasks and missions to perform to maintain their morale, and letting them hate or resent him for it if they will. But over time the captain really does lose the ability to decide anything and Charles becomes the ship’s dictator. This is complicated by the fact that he discovers the woman who had suggested they become a couple, Ingrid, in someone else’s bed though she swears she was only doing it for therapeutic purposes. They split up and Charles pairs off with the Chinese planetologist, Chi-Yuen Ai-Ling, leading to a number of sexy descriptions of her naked body. But Ingrid continues to hold a torch for him and he for her. That’s the spine of the ‘human interest’ part of the novel.

Hundreds of millions of years have passed and indeed, in the last 40 pages or so a character lets slips that it must be over a billion years since they left earth.

it’s at this stage that the book becomes truly visionary. For, after some delay and conferring with colleagues, the astronomer comes to the captain and Reymont and Lindgren to announce that… the universe itself is changing. The galaxies they are flying through no longer contain fit young stars. Increasingly what they’re seeing through their astronomical instruments (not the naked eye) is that the galaxies are made of low intensity red dwarfs.

The universe is running down.

So many billion years have passed – one character estimates one hundred billion years (p.170) that they have travelled far into ‘the future’ and are witnessing the end of the universe. The stars are going out and the actual space of the universe is contracting.

Anderson’s vision is based on the theory that the universe began in a big bang, has and will expand for billions of years but will eventually reach a stage where the initial blast of energy from the bang is so dispersed that it is countered by the cumulative gravity of all the matter in the universe – which will stop it expanding and make it slowly and then with ever-increasing speed, hurtle towards a ‘Big Crunch’ when all the matter in the universe returns to the primal singularity.

Face with this haunting, terrifying fact, the scientists again make calculations and act on a hunch. They guess that the singularity won’t actually become a minute particle but will be shrouded in ‘en enormous hydrogen envelope’ (p.175), the simplest chemical, and calculate that the ship will be flying so fast that it will survive the Big Crunch and live on to witness the creation of the next universe.

‘The outer part of that envelope may not be too hot or radiant or dense for us. Space will be small enough, though, that we can circle around and around the monobloc as a kind of satellite. When it blows up and space starts to expand again, we’ll spiral out ourselves.’ (Reymont, p.175)

And this is what happens. Anderson gives a mind bogging description of the ship reaching such an infinitesimal value of tau that it flies right through the Big Crunch and out into the new universe which explodes outwards (pp.181-3).

Indeed it is travelling so fast, and time outside is moving so fast, that they can chose how many billions of years into the history of the new universe they want to stop (p.184). A quick calculation suggests that it took about 10 billion years for a plenty like earth to come into being and establish the conditions for life to evolve, and so they calculate their deceleration to take place that far into the future of this new universe.

Epilogue

And this is what they do, and the last few pages cut to Reymont and Ingrid, the lovers we met in the opening pages falling dreamily in love, now lying under a tree on a planet which has an earth-like atmosphere but blue vegetation, three moons and all sorts of weird fauna and flora, as they plan their lives together (pp.188-190)

We left plausibility behind a long time ago. Instead the book turns into an absolutely gripping rollercoaster of a ride, one of the most genuinely mind-blowing and gripping stories I’ve ever read. What a trip!

Style

the foregoing summary may give the impression the story is told in language as clear as an instruction manual, but this would be wrong.

Putting the plot to one side, one of the most striking features of Tau Zero is its prose style – an odd and ungainly variant of standard English which makes you pause on every page.

Leonora Christine was nearing the third year of her journey, or the tenth year as the stars counted time, when grief came upon her. (p.63)

Anderson was born in America (in 1926) but his mother took him as a boy to live in Denmark where she’d originally come from, until the outbreak of war forced them to return. For this or the general fact of growing up in an immigrant Scandinavian family, Anderson’s English is oddly stilted and phrased. It often sounds like it’s been translated from a Norse saga.

She gave him cheerful greeting as he entered. (p.52)

They would live out their lives, and belike their children and grandchildren too (p.53)

He stood moveless (p.58)

Nor would he have stopped to dress, had he been abed. (p.64)

Telander must perforce smile a bit as he went out the door. (p.69)

Fedoroff spoke. His words fell contemptuous. (p.80)

He clapped the navigator’s back in friendly wise. (p.159)

She rested elbow on head, forehead on hand. (p.161)

Every pages has sentences containing odd kinks away from natural English. As a small example it’s typified by the way Anderson refers throughout the story not to the ship’s ‘crew’, but to its folk. Another consistent quirk is the way people don’t experience emotions or psychological states, these, in the form of abstract nouns, come over them.

Soberness had come upon her. (p.100)

Dismay sprang forth on Williams. (p.105)

Anger still upbore the biologist. (p.106)

Dismay shivered in her. (p.116)

Hardness fell from him. (p.125)

Weight grabbed at Reymont. (.167)

Sometimes he achieves a kind of incongruous poetry by accident.

Footsteps thudded in the mumble of energies. (p.70)

Ingrid Lindgren regarded him for a time that shivered. (p.71)

The ship jeered at him in her tone of distant lightnings. (p.84)

Sometimes it makes the already challenging technical explanations just that little bit more impenetrable.

Then again, maybe this slightly alien English helps to create a sense of mild dislocation which is not inappropriate for a science fiction story, especially one which takes us right to the edge of the universe and then beyond!

Related links

Other science fiction reviews

1888 Looking Backward 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy – Julian West wakes up in the year 2000 to discover a peaceful revolution has ushered in a society of state planning, equality and contentment

1890 News from Nowhere by William Morris – waking from a long sleep, William Guest is shown round a London transformed into villages of contented craftsmen

1895 The Time Machine by H.G. Wells – the unnamed inventor and time traveller tells his dinner party guests the story of his adventure among the Eloi and the Morlocks in the year 802,701

1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells – Edward Prendick is stranded on a remote island where he discovers the ‘owner’, Dr Gustave Moreau, is experimentally creating human-animal hybrids

1897 The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells – an embittered young scientist, Griffin, makes himself invisible, starting with comic capers in a Sussex village, and ending with demented murders

1898 The War of the Worlds – the Martians invade earth

1899 When The Sleeper Wakes/The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells – Graham awakes in the year 2100 to find himself at the centre of a revolution to overthrow the repressive society of the future

1899 A Story of the Days To Come by H.G. Wells – set in the same future London as The Sleeper Wakes, Denton and Elizabeth defy her wealthy family in order to marry, fall into poverty, and experience life as serfs in the Underground city run by the sinister Labour Corps

1901 The First Men in the Moon by H.G. Wells – Mr Bedford and Mr Cavor use the invention of ‘Cavorite’ to fly to the moon and discover the underground civilisation of the Selenites

1904 The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth by H.G. Wells – scientists invent a compound which makes plants, animals and humans grow to giant size, prompting giant humans to rebel against the ‘little people’

1905 With the Night Mail by Rudyard Kipling – it is 2000 and the narrator accompanies a GPO airship across the Atlantic

1906 In the Days of the Comet by H.G. Wells – a comet passes through earth’s atmosphere and brings about ‘the Great Change’, inaugurating an era of wisdom and fairness, as told by narrator Willie Leadford

1908 The War in the Air by H.G. Wells – Bert Smallways, a bicycle-repairman from Kent, gets caught up in the outbreak of the war in the air which brings Western civilisation to an end

1909 The Machine Stops by E.M. Foster – people of the future live in underground cells regulated by ‘the Machine’ until one of them rebels

1912 The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Professor Challenger leads an expedition to a plateau in the Amazon rainforest where prehistoric animals still exist

1912 As Easy as ABC by Rudyard Kipling – set in 2065 in a world characterised by isolation and privacy, forces from the ABC are sent to suppress an outbreak of ‘crowdism’

1913 The Horror of the Heights by Arthur Conan Doyle – airman Captain Joyce-Armstrong flies higher than anyone before him and discovers the upper atmosphere is inhabited by vast jellyfish-like monsters

1914 The World Set Free by H.G. Wells – A history of the future in which the devastation of an atomic war leads to the creation of a World Government, told via a number of characters who are central to the change

1918 The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs – a trilogy of pulp novellas in which all-American heroes battle ape-men and dinosaurs on a lost island in the Antarctic

1921 We by Evgeny Zamyatin – like everyone else in the dystopian future of OneState, D-503 lives life according to the Table of Hours, until I-330 wakens him to the truth

1925 Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov – a Moscow scientist transplants the testicles and pituitary gland of a dead tramp into the body of a stray dog, with disastrous consequences

1927 The Maracot Deep by Arthur Conan Doyle – a scientist, engineer and a hero are trying out a new bathysphere when the wire snaps and they hurtle to the bottom of the sea, there to discover…

1930 Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon – mind-boggling ‘history’ of the future of mankind over the next two billion years

1938 Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis – baddies Devine and Weston kidnap Ransom and take him in their spherical spaceship to Malacandra aka Mars,

1943 Perelandra (Voyage to Venus) by C.S. Lewis – Ransom is sent to Perelandra aka Venus, to prevent a second temptation by the Devil and the fall of the planet’s new young inhabitants

1945 That Hideous Strength: A Modern Fairy-Tale for Grown-ups by C.S. Lewis– Ransom assembles a motley crew to combat the rise of an evil corporation which is seeking to overthrow mankind

1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell – after a nuclear war, inhabitants of ruined London are divided into the sheep-like ‘proles’ and members of the Party who are kept under unremitting surveillance

1950 I, Robot by Isaac Asimov – nine short stories about ‘positronic’ robots, which chart their rise from dumb playmates to controllers of humanity’s destiny

1950 The Martian Chronicles – 13 short stories with 13 linking passages loosely describing mankind’s colonisation of Mars, featuring strange, dreamlike encounters with Martians

1951 Foundation by Isaac Asimov – the first five stories telling the rise of the Foundation created by psychohistorian Hari Seldon to preserve civilisation during the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1951 The Illustrated Man – eighteen short stories which use the future, Mars and Venus as settings for what are essentially earth-bound tales of fantasy and horror

1952 Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov – two long stories which continue the future history of the Foundation set up by psychohistorian Hari Seldon as it faces attack by an Imperial general, and then the menace of the mysterious mutant known only as ‘the Mule’

1953 Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov – concluding part of the ‘trilogy’ describing the attempt to preserve civilisation after the collapse of the Galactic Empire

1953 Earthman, Come Home by James Blish – the adventures of New York City, a self-contained space city which wanders the galaxy 2,000 years hence powered by spindizzy technology

1953 Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury – a masterpiece, a terrifying anticipation of a future when books are banned and professional firemen are paid to track down stashes of forbidden books and burn them

1953 Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke a thrilling narrative involving the ‘Overlords’ who arrive from space to supervise mankind’s transition to the next stage in its evolution

1954 The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov – set 3,000 years in the future when humans have separated into ‘Spacers’ who have colonised 50 other planets, and the overpopulated earth whose inhabitants live in enclosed cities or ‘caves of steel’, and introducing detective Elijah Baley to solve a murder mystery

1956 The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov – 3,000 years in the future detective Elijah Baley returns, with his robot sidekick, R. Daneel Olivaw, to solve a murder mystery on the remote planet of Solaria

1956 They Shall Have Stars by James Blish – explains the invention – in the near future – of the anti-death drugs and the spindizzy technology which allow the human race to colonise the galaxy

1957 The Black Cloud by Fred Hoyle – a vast cloud of gas heads into the solar system, blocking out heat and light from the sun with cataclysmic consequences on Earth, until a small band of maverick astronomers discovers that the cloud contains intelligence and can be communicated with

1959 The Triumph of Time by James Blish – concluding story of Blish’s Okie tetralogy in which Amalfi and his friends are present at the end of the universe

1961 A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke a pleasure tourbus on the moon is sucked down into a sink of moondust, sparking a race against time to rescue the trapped crew and passengers

1962 A Life For The Stars by James Blish – third in the Okie series about cities which can fly through space, focusing on the coming of age of kidnapped earther, young Crispin DeFord, aboard New York

1962 The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick In an alternative future America lost the Second World War and has been partitioned between Japan and Nazi Germany. The narrative follows a motley crew of characters including a dealer in antique Americana, a German spy who warns a Japanese official about a looming surprise German attack, and a woman determined to track down the reclusive author of a hit book which describes an alternative future in which America won the Second World War

1963 Planet of the Apes by Pierre Boulle French journalist Ulysse Mérou accompanies Professor Antelle on a two-year space flight to the star Betelgeuse, where they land on an earth-like plane to discover that humans and apes have evolved here, but the apes are the intelligent, technology-controlling species while the humans are mute beasts

1968 2001: A Space Odyssey a panoramic narrative which starts with aliens stimulating evolution among the first ape-men and ends with a spaceman being transformed into galactic consciousness

1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick In 1992 androids are almost indistinguishable from humans except by trained bounty hunters like Rick Deckard who is paid to track down and ‘retire’ escaped andys

1969 Ubik by Philip K. Dick In 1992 the world is threatened by mutants with psionic powers who are combated by ‘inertials’. The novel focuses on the weird alternative world experienced by a group of inertials after a catastrophe on the moon

1970 Tau Zero by Poul Anderson – spaceship Leonora Christine leaves earth with a crew of fifty to discover if humans can colonise any of the planets orbiting the star Beta Virginis, but when its deceleration engines are damaged, the crew realise they need to exit the galaxy altogether in order to find space with low enough radiation to fix the engines, and then a series of unfortunate events mean they find themselves forced to accelerate faster and faster, effectively travelling through time as well as space until they witness the end of the entire universe

1971 Mutant 59: The Plastic Eater by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis – a genetically engineered bacterium starts eating the world’s plastic

1973 Rendezvous With Rama by Arthur C. Clarke – in 2031 a 50-kilometre long object of alien origin enters the solar system, so the crew of the spaceship Endeavour are sent to explore it

1974 Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick – America after the Second World War has become an authoritarian state. The story concerns popular TV host Jason Taverner who is plunged into an alternative version of this world in which he is no longer a rich entertainer but down on the streets among the ‘ordinaries’ and on the run from the police. Why? And how can he get back to his storyline?

1974 The Forever War by Joe Haldeman The story of William Mandella who is recruited into special forces fighting the Taurans, a hostile species who attack Earth outposts, successive tours of duty requiring interstellar journeys during which centuries pass on Earth, so that each of his return visits to the home planet show us society’s massive transformations over the course of the thousand years the war lasts.

1981 The Golden Age of Science Fiction edited by Kingsley Amis – 17 classic sci-fi stories from what Amis considers the Golden Era of the genre, namely the 1950s

1982 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke – Heywood Floyd joins a Russian spaceship on a two-year journey to Jupiter to a) reclaim the abandoned Discovery and b) investigate the monolith on Japetus

1984 Neuromancer by William Gibson – burnt-out cyberspace cowboy Case is lured by ex-hooker Molly into a mission led by ex-army colonel Armitage to penetrate the secretive corporation, Tessier-Ashpool at the bidding of the vast and powerful artificial intelligence, Wintermute

1986 Burning Chrome by William Gibson – ten short stories, three or four set in Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ universe, the others ranging across sci-fi possibilities, from a kind of horror story to one about a failing Russian space station

1986 Count Zero by William Gibson –

1987 2061: Odyssey Three by Arthur C. Clarke – Spaceship Galaxy is hijacked and forced to land on Europa, moon of the former Jupiter, in a ‘thriller’ notable for Clarke’s descriptions of the bizarre landscapes of Halley’s Comet and Europa

1988 Mona Lisa Overdrive by William Gibson – third of Gibson’s ‘Sprawl’ trilogy in which street-kid Mona is sold by her pimp to crooks who give her plastic surgery to make her look like global simstim star Angie Marshall who they plan to kidnap but is herself on a quest to find her missing boyfriend, Bobby Newmark, one-time Count Zero, while the daughter of a Japanese ganster who’s sent her to London for safekeeping is abducted by Molly Millions, a lead character in Neuromancer

1990 The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling – in an alternative history Charles Babbage’s early computer, instead of being left as a paper theory, was actually built, drastically changing British society, so that by 1855 it is led by a party of industrialists and scientists who use databases and secret police to keep the population under control