For over 700 years London was the scene of public executions, a practice which wove itself into the city’s history and popular culture. This excellent and imaginatively designed exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands explores all aspects of public executions in London, using a combination of artifacts, letters, informative videos, songs and voices, paintings, engravings and caricatures, and some really gruesome exhibits.

Above all, it is amazingly comprehensive – it touches on all the aspects of the subject I’d expected beforehand but goes on to explore all kinds of nooks and crannies I’d never have thought of. I’d never thought about the effort some condemned prisoners put into being well dressed for their trip to the gallows. Well, the exhibition tells the stories of condemned men and women who went to great lengths to look their best on their death day, and even has the fine dress and fancy suit worn by a female and male executionee:

- on the left, the ‘white muslin gown, a handsome worked cap and laced boots’ worn by Eliza Fenning who was hanged for attempting to poison her employers

- to the right, the ‘superb suit of white and silver, being the clothes in which he was married’ worn by Laurence Shirley, Earl Ferrers, was hanged on 5 May 1760 for the murder of his steward John Johnson, whom he shot in a rage

Final clothing section in the ‘Executions’ exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands © Museum of London

(The door on the right of this photo is one of the three doors you had to pass through to enter Newgate Prison. The architect George Dance thoughtfully positioned swags of chains and shackles over the main entrance door at Newgate to terrify and intimidate new prisoners.)

I’d never thought about what happened to the bodies of the hanged after their execution. Turns out that from the mid-16th century the bodies of executed criminals were given to the Company of Barber-Surgeons and the Royal College of Surgeons for dissection and medical research. The thought of being dissected filled the condemned with horror. Fights could break out at executions as friends and family of the deceased would attempt to stop the surgeons claiming bodies. In the same spirit I had no idea that life sized casts of the heads of the executed were often made – there’s a selection of them on display here, which, as the nineteenth century progressed, were used to study ‘criminal’ physiognomy. Alternatively, the casts of notorious criminals were kept in a special display at Newgate where they could be viewed by visitors, who included Charles Dickens.

I knew that broadsheets and leaflets were often sold at executions which claimed to give the last speech of the condemned man, along with a ballad poem describing his fate – but I’d never had the opportunity to read some of these before. Ditto the last letters condemned men wrote to their loved ones. There’s not only letters but rings and coins sent by those condemned to transportation instead of execution in the mid-nineteenth century.

I knew that prisoners in gaol were often shackled but I don’t think I’ve seen a collection of the different types of handcuffs, shackles and ‘waist belts’ used for this purpose on display before. Apparently the weight of shackles prisoners were manacled with sometimes meant they could barely move. As well as direct punishment of the prisoner, the sound of all this metalwork clanking through the echoing vaults of the grim prisoner had a demoralising and terrifying psychological effect on other inmates. The practice of routinely keeping prisoners shackled in irons ceased in the 1820s.

Shackles and handcuffs used in Newgate Prison at the ‘Executions’ exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands © Museum of London

I’ve certainly never seen a real actual gibbet before and I didn’t know that they didn’t come in a standard size, but that a gibbet ‘tailor’ took the corpse’s measurements and built the gibbet to perfectly fit. In line with the state of the art interactivity of the exhibition, the display of this real-life gibbet had a gruesome audio soundtrack with the noise of flies buzzing round the rotting corpse.

I was at first puzzled why the gibbet was so elaborate but realised that a lifeless body would flop in all directions unless its limbs were very strictly compassed and controlled. The effect can be seen in this illustration of the body of the notorious pirate Captain Kidd.

More criminals were gibbeted in the greater London area than elsewhere in the country. The bodies of murders and highwaymen were gibbeted on heaths located on the outskirts of London and main highways into the capital, especially on the wide open Hounslow Heath which became famous for the number of gibbets.

Capital punishments

Between the first recorded execution at Tyburn in 1196 and the last public execution in 1868, there were tens of thousands of executions in London. Nobody knows the precise number because records weren’t kept before the 18th century.

Right at the start there’s a wall-sized video which shows a scrolling list of all the offences which carried the penalty of capital punishment. By the end of the 18th century some 200 crimes were punishable by death in a list which became known as the ‘Bloody Code’. London’s courts condemned more people to die than those in the rest of the country combined.

Scrolling list of capital offences at the ‘Executions’ exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands © Museum of London

Types of execution

Most ordinary criminals were hanged. More florid ways of being despatched were reserved for VIPs.

1. Drawing, hanging and quartering

An ancient punishment for treason, the prisoner was ‘drawn’ or dragged from prison to the execution site, hanged until they were nearly dead, then castrated, disembowelled, beheaded and cut into quarters. Thee practice continued into the 19th but by then prisoners were hanged first and then beheaded.

there’s a vivid engraving of the fate of the Gunpowder Plotters who, after being found guilty in 1606, were publicly executed over two days in St Paul’s Churchyard and Old Palace Yard, Westminster, where they were dragged by horses through the streets, hanged, castrated, disembowelled and cut into pieces.

2. Burning

In 1401 an Act of Parliament made burning the punishment for heresy. It aimed to ‘strike fear into the minds’ of people who questioned the teachings of the church. Women convicted of murdering their husbands or counterfeiting could also be burned to death. By the 18th century they were strangled first.

The exhibition features illustrations of the Protestant martyrs burned at the stake at Smithfield. Over 280 religious dissenters were burned at the stake during the five-year reign of Mary I, known as ‘Bloody Mary’. Besides Smithfield others were burned to death at Stratford-le-Bow, Barnet, Islington, Southwark, Uxbridge, Westminster and throughout England.

Woodcut depicting John Rogers, the first of the ‘Marian martyrs’, being burned at the stake in Smithfield (1555)

3. Boiling

Death by boiling was a rare punishment. In 1531 a cook named Richard Roose poisoned the porridge of the household of Bishop John Fisher, causing two deaths. Henry VIII was so disgusted he declared this crime treason and Parliament passed the ‘Acte for Poysoning’ ordering those who murdered by poison to be boiled to death. Roose was boiled at Smithfield. Eleven years later Margaret Davies suffered the same fate for poisoning four people. Edward VI abolished this execution method in 1547.

4. Beheading

Members of the nobility condemned for treason were often beheaded out of respect for their high status, rather than suffering the agony and humiliation of drawing, hanging and quartering. Most beheadings took place in public on Tower Hill before a large crowd.

5. Hanging

Most ordinary criminals were executed by hanging. There appear to have been two methods. Initially the condemned were placed under a gallows (in the very early period just a tree) standing on a cart. A rope was noosed round their neck and the cart slowly pulled away by horses or oxen till the condemned fell off the back of it and was left dangling. This could be a fairly slow, excruciating death. Laster the ‘short drop’ method was introduced, where the condemned stood on a raised platform and, with the flick of a handle, a trapdoor opened underneath them, dropping them through and making it more likely their neck would snap with the sudden ratchet of the noose. But both methods were far from foolproof and family members or the executioner often pulled the legs of the hanged person to speed up their death.

Places of execution

In the City of London you are never more than 500 metres from a former place of execution. London was packed with them. Early on in the exhibition there’s a useful wall-sized video, with a bench to sit and watch it, which shows maps of London from early medieval times onwards, showing not only ow its street plan grew and developed (interesting in itself) but where the ever-growing number of places of execution were sited (indicated on the maps by entertaining ochre blotches of blood).

1. Smithfield

In the medieval and Tudor periods Smithfield was used for various public purposes, including a livestock market, fairs and executions, as in the burning of the Protestant martyrs mentioned above.

2. Tyburn

Tyburn stood slightly to one side of the current position of Marble Arch at the north-east tip of Hyde Park. It served as London’s principal site of execution for around 600 years. The earliest account records the execution of William FitzOsbert in 1196. Until the late 18th century it was a semi-rural location, easy to get to and easy for crowds to assemble and watch the spectacle.

A huge amount of popular tradition and iconography grew up around the public hanging of criminals at Tyburn. The exhibition contains umpteen engravings and pictures, stores and facts, not least about the carnivalesque atmosphere which reigned along the route of carts transporting convicted criminals from Newgate Prison, via St Giles’s-in-the-Fields church and then along what is now Oxford Street. Many of the condemned went to their execution drunk, in fact it became customary for the cart to stop off at a pub at St Giles where the executioner and victim shared a last pint of beer. This became known as ‘the St Giles Bowl’.

Bernard Mandeville wrote that ‘all the way from Newgate to Tyburn, is one continued Fair, for whores and rogues of the meaner sort.’

In 1961 construction began on new pedestrian subways by Marble Arch and the excavators found large quantities of human bones around the site of the Tyburn gallows which archaeologists presume are the remains of the executed who were buried where they died.

A lot of slang and catchphrases grew up about the place. The scaffold was known as ‘the Tyburn tree’. To ‘take a ride to Tyburn’ (or simply ‘go west’) was to go to one’s hanging. The ‘Lord of the Manor of Tyburn’ was the public hangman while ‘dancing the Tyburn jig’ was the act of being hanged because of the wriggling, dancing movement of the hanged in their last moments.

The last execution at Tyburn was of John Austin, a highwayman, on 3 November 1783.

3. Newgate

With the closure of Tyburn London’s public executions moved to the open space in front of the rebuilt Newgate Prison. This was to be London’s principal site of public execution for the next 85 years until public executions were discontinued in 1868.

The move meant the end of the great public procession from Newgate to Tyburn. It was an assertion by the authorities of their control over the timing and atmosphere of the executions. The Newgate scaffold featured two beams with capacity for up to 12 hangings.

Newgate Prison itself closed in 1902. The demolition of one of London’s most iconic buildings aroused considerable public interest and relics of the prison were sold at auction. A keystone from the main doorway is on display here, as is one of the heavy wood-and-metal doors (see first photo).

4. Horsemonger Lane

Public executions at Horsemonger Lane in Southwark took place on the roof of the gatehouse, making them highly visible to spectators.

5. Tower Hill

A small number of noble men and women, soldiers and spies were privately executed within the walls of the Tower of London. Many more – at least 120 between 1388 and 1780 – were executed in public on Tower Hill. Beheadings and hangings, were common enough for the ‘posts of the scaffold’ to become a landmark. It was here that Thomas, Earl of Strafford, a key ally of Charles I, was executed on 12 May 1641, as part of the political divisions which opened up before the outbreak of civil war the following year.

6. Execution Dock

On the Thames near Wapping, Execution Dock was used for more than 400 years to execute pirates, smugglers and mutineers who had been sentenced to death by Admiralty courts. The ‘dock’ consisted of a scaffold for hanging. The last executions there took place in 1830. Just up the river at Blackwall Reach where it bends bodies of convicts were gibbeted so as to be more visible to boats entering the city.

7. Charing Cross

Public executions took place at Charing Cross in the 16th and 17th centuries. A pillory that locked the head and hands of a criminal into a wooden frame for public humiliation was later erected at the site.

8. New Palace Yard and Westminster Hall

The area around the Palace of Westminster was used for public executions, the display of body parts and pillorying criminals.

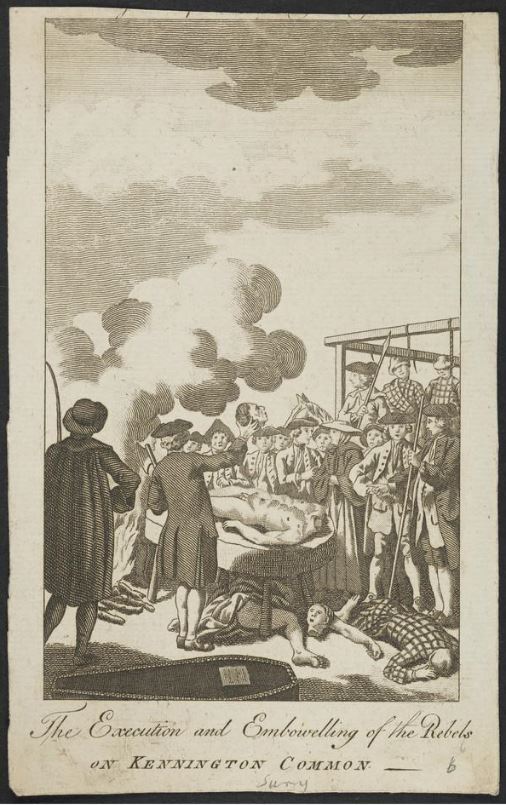

9. Kennington Common

From at least 1678 until 1800 Kennington Common was the principal execution site for the county of Surrey.

10. Cheapside

Temporary gallows were erected on several occasions at Cheapside between the 14th and 17th centuries. They were in place for over 100 days in 1554 following the execution of two rebels involved in a Protestant uprising against Mary I.

Ordinary criminals and reprieves

The exhibition contains the story of what feels like 50 or so ordinary criminals, whose names are preserved for some or other aspect of their crime or their trial or their plea for pardon or the way they died. One by one their pitiful stories build up into an upsetting profile of the generally poor and wretched who committed often petty crimes and went to their deaths miserably.

As the number convicted of capital offences rose in the later 18th century the number of reprieves increased, if only to manage down the number of executions which threatened to swamp the system. The exhibition features letters written by the condemned, their friends and relatives and influential contacts. I like the story of the Dane Jørgen Jørgenson, who was convicted in 1820 of robbery but managed to get a letter to the Duke of Wellington for whom he had worked as a during the Napoleonic wars. The exhibition includes a letter from the Duke pardoning Jørgenson on condition he ‘transports’ himself out of the country.

The most famous victim: Charles I

Probably the most famous execution ever to take place in London was not of a common criminal or aristocratic traitor but of the king himself, namely Charles I, brought to trial by the Puritan junta and found guilty of treason against his own people. The exhibition devotes a large case to his execution, on 31 January 1649, with several contemporary illustrations and a number of artefacts said to be linked to it, namely a pair of royal gloves he was said to have taken with him, and even the silk undershirt he insisted on wearing to prevent him shivering with cold (it was January in London) which, he told his attendant, Sir Thomas Herbert, might be misinterpreted as fear.

Later on in the exhibition there are several objects pertaining to the punishment of his killers. 59 leading Puritan generals and MPs signed the king’s death warrant and so came to be known by their enemies as the ‘regicides’. On his Restoration in 1660, Charles II had special agents arrest any of the regicides living in England and track down those who had fled abroad and assassinate them.

Three of the leading regicides, Oliver Cromwell, John Bradshaw and Henry Ireton, had already died of natural causes and been buried at Westminster Abbey, but in 1661 Charles’s Cavalier Parliament ordered their bodies to be exhumed, executed and decapitated. Their heads were displayed on poles outside Westminster Hall. Cromwell’s head remained there until 1685.

The most famous criminal: Jack Sheppard

John ‘Jack’ Sheppard was convicted of robbery in 1724, aged 22. Sheppard was one of London’s greatest criminal heroes. Notorious for escaping multiple times from Newgate, he became a symbol of freedom for London’s working classes. An apprentice carpenter, Jack fell into a life of thieving, reputably led astray by ‘bad company and lewd women’. Although eventually executed at Tyburn at the age of 22, his effrontery and skill in challenging authority ensured his story was recounted in popular books and plays for generations. The artist James Thornhill paid one shilling and sixpence to visit him in his cell to draw this portrait.

In the 1850s the campaigning journalist Henry Mayhew discovered that ‘chapbooks’ recounting Sheppard’s exploits were hugely popular in low lodging houses, where they were read aloud to illiterate youths. He interviewed 13 boys who confessed to thieving in order to pay for a theatre ticket for the current play about Jack’s life.

The most famous executioner: Jack Ketch

In 1685, the Duke of Monmouth, illegitimate son of Charles II, led a rebellion to seize the throne from his uncle, James II. The rebellion was defeated, Monmouth was captured, condemned for high treason and beheaded on Tower Hill. Despite asking to be killed with one clean blow, Monmouth’s executioner, Jack Ketch, made a right monkeys of the procedure, failing to despatch the Duke after two strikes with an axe and being forced to resort to a knife to cut through the neck while the Duke made a grim effort to rise from the block to the horror of onlookers. As a result of this heroic failure Ketch’s name became infamous and, eventually, became a byword for public executioners, who, by and large preferred to keep their identities secret.

Transportation

A final section of the exhibition explains how crimes which had previously resulted in execution were amended to ‘transportation’ to the colonies, generally meaning Australia. In fact the first convicts transported out of England had been despatched as long ago as 1718, when they were sent to America to supply plantations there with labour. Thus Moll Flanders, heroine of Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel, is convicted of a capital offence but gets it commuted to transportation to British America.

Transport to America ended when that country became independent in 1776 but, as luck would have it, just a few years earlier (in 1770) Australia had been discovered and provisionally mapped by Captain James Cook. Between 1788 and 1868 over 160,000 convicts were sent to Australia from England and other parts of the Empire.

The exhibition includes a few paintings of the first settlement, which are fairly predictable – but I had never heard about ‘convict tokens’ before. Apparently, convicts awaiting transportation presented loved ones with smoothed coins engraved with messages of affection. Often created by prisoners skilled in metalwork, for a fee, the tokens could be highly decorative and became known as ‘leaden hearts’. Half a dozen examples are on display here.

A convict’s love token from the ‘Executions’ exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands © Museum of London

The campaign to abolish public executions

The advent of Queen Victoria to the throne in 1837 marked a sea change in social attitudes. The young queen consciously rebelled against the louche morals of her rakish predecessor, William IV. She wanted a chaste, sober court and her high moral tone and sincere Anglicanism set the style for the new reign among the aristocracy and aspiring upper middle classes. There was a general wish to make all aspects of public life more respectable and, in time, the new mood extended to the utterly disreputable practice of public executions, with all their opportunities for immorality of every description which this exhibition has chronicled.

In 1840 William Makepeace Thackeray attended the execution of the Swiss valet François Courvoisier, executed for murdering his master, Lord William Russell. He wrote that ‘I feel myself ashamed and degraded at the brutal curiosity which took me to that brutal sight…I came away…that morning with a disgust for murder, but it was for the murder I saw done.’

In 1849 Charles Dickens had attended the execution of Maria and Frederick Manning and wrote a furious letter to The Times criticising the ‘inconceivably awful behaviour’ of the crowd. Describing public execution as a ‘moral evil’, he doubted communities could prosper where such scenes of ‘horror and demoralisation’ could take place.

Prison reform had been an issue since the start of the nineteenth century and combined with the campaign to abolish public executions. The exhibition cites the MP Thomas Hobhouse in 1866 arguing that the spectacle, instead of instilling fear of crime and respect for the law, resulted in the crowds who became ‘hardened and literally acquired a taste for blood.’

The exhibition features a powerful satirical cartoon published in Punch magazine mocking the commercialisation of state executions. The scaffold is a theatrical stage with a sign for ‘opera glasses’ and a booth selling tickets while the mixed crowd is worked by hawkers and costermongers. ‘Ere’s lots o’ the rope which ‘ung the late lamented Mr Greenacre, only a penny an inch!’

After several attempts to move a bill in Parliament, the Capital Punishment Amendment Act was finally passed in 1868 public executions in Britain were officially banned. The last person to be publicly executed in London was the Irish republican Michael Barrett, on 26 May 1868. Three days later the practice was outlawed.

But it wasn’t the abolition of the death penalty, though. Another century was to pass before that occurred. Only in 1965 was the death penalty for murder in Britain suspended for five years and in 1969 was this made permanent. And it wasn’t until 1998 that the death penalty in Britain was finally abolished for all crimes. The last people executed in the UK were Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans on 13 August 1964.

Amnesty International

Things take a very earnest turn at the end of the exhibition with a large video screen showing an interview with Paul Bridges from Amnesty International. He reminds us that 55 countries still retain the death penalty (although, admittedly, many have not used it for some time). Nonetheless, Amnesty International recorded 579 executions in 18 countries in 2021.

Summary

This is an outstandingly interesting, comprehensive, thought-provoking, sometimes funny, but mostly grisly and gruesome exhibition, beautifully staged, with absorbing interactive elements. You have two more weeks to catch it.

Related links

- Executions continues @ the Museum of London Docklands until 16 April 2023

- The Execution Sites of London on the Historic UK website

- The History of Hanging on the Historic UK website