Before I went I’d read some disparaging reviews of this exhibition – but I found it really interesting, thought-provoking, full of wonderful paintings and prints and drawings, and making all kinds of unexpected connections. And big, much bigger than I expected.

The premise is simple: Vincent van Gogh came to live in England in 1873, at the age of 20. He lived in London for nearly three years, developing an intimate knowledge of the city and a great taste for English literature and painting. The exhibition:

- explores all aspects of van Gogh’s stay in London, with ample quotes from his letters to brother Theo praising numerous aspects of English life and London – and contains several rooms full of the English paintings and prints of contemporary urban life which he adored

- then it explores the development of van Gogh’s mature style and the many specific references he made back to themes and settings and motifs he had first seen in London, in London’s streets and galleries

- finally, the exhibition considers the impact van Gogh had on British artists

- as a result of the inclusion of his pictures in the famous 1910 exhibition Post-Impressionist Painting

- between the wars when van Gogh’s letters were published and fostered the legend of the tormented genius, the man who was too beautiful and sensitive for this world

- and then how van Gogh’s reputation was further interpreted after the debacle of the Second World War

Gustave Doré

The first three rooms deal with the London that van Gogh arrived in in 1873. Among the highlights was a set of seventeen prints from Gustave Doré’s fabulous book London, a pilgrimage, which had been published only the year before, 1872. All of these are marvellous and the first wall, the wall facing you as you enter the exhibition, is covered with an enormous blow-up of Doré’s illustration of the early Underground.

Frankly, I could have stopped right here and admired Doré’s fabulous draughtsmanship and social history, as I looked at the wall covered with seventeen of the prints from the book which we know van Gogh owned and revered.

It’s the basis of the first of many links and threads which run through the show because, many years later, when van Gogh had developed his mature style but had also developed the mental illness that was to plague him, during his confinement in a mental hospital, he was to paint a faithful copy of Doré’s depiction of inmates in Newgate prison but in his own blocky style, to express his own feelings.

Social realism

Van Gogh had come to London because he had got a job with the art dealing firm Goupil, which was part of the fast-growing market for the popular prints and art reproductions which were informally referred to as ‘black and whites’.

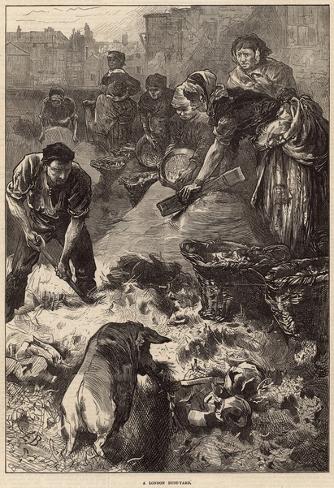

VanGogh ended up with a collection of over 2,000 of these English prints, and admired them for their realistic depictions of contemporary urban scenes, especially among the poor. I was fascinated to learn that there was a set of socially-committed artists who all drew for The Graphic magazine, including Luke Fildes, Edward Dalziel, Frank Holl, and Edwin Buckman. The exhibition includes quite a few black and white social realist prints by artists from this circle and, as with the Doré, I could have studied this stuff all day long.

The curators related these blunt depictions of London life back to the novels of Charles Dickens, who we know van Gogh revered (in this instance the rubbish dump motif linking to the dust yard kept by the Boffin family, the central symbol of his last, finished novel, Our Mutual Friend). As Vincent was to write during his first year as a struggling artist:

My whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes and these artists draw.

But these illustrations by numerous London artists are also here because Vincent copied them. Next to the Buckman image of a dustyard is a graphite sketch of dustmen by Vincent. Next to a Luke Filde image of the homeless and poor, is a van Gogh drawing of a public soup kitchen.

Other images include one of surly roughs waiting for the pub to open and a hooligan being arrested. Next to them all are van Gogh’s own earliest sketches and drawing, including a series he did of a homeless single mother begging on the streets, Sien Hoornik, who he took in and fed and had model for him (fully clothed) in a variety of postures of hopelessness and forlornness. And variations on the theme of tired, poor old men.

This is the Vincent who set his heart on becoming a vicar and did actually preach sermons at London churches, as well as crafting skilled sketches of churches in the letters he sent to brother Theo, and which are displayed here.

The example of old masters

But it wasn’t just magazine and topical illustration which fired Vincent’s imagination. The curators have also included a number of big classic Victorian paintings – by John Constable and John Millais among others – to give a sense of what ‘modern’ art looked like to the young van Gogh.

He was not yet a painter, in fact he didn’t know what he wanted to be. But the curators have hung the sequence, and accompanied them by quotes from letters, to show that, even in his early 20s, he was an acute observer of other people’s art, not only Victorian but other, older, pictures he would have seen at the National Gallery.

Several of these classic paintings depict an open road between a line of trees and, as the room progresses, the curators have hung next to them van Gogh’s later depictions of the same motif, showing early versions of the motif done in a fairly rudimentary approach, the oil laid on thick and heavy and dark…

And then next to these, suddenly, we have the first works of his mature style in which his art and mind have undergone a dazzling liberation.

Path in the Garden of the Asylum by Vincent van Gogh (1889) © Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

The triumph of distortion

One of the things you can see evolving is his depiction of faces. Early on, he’s not very good. There’s a set of faces of what look like jurymen, as well as individual portraits of working men and women, and often they are either expressionless blocks, or a bit cack-handed, a bit lop-sided. Even the numerous sketches of Sien Hoornik are better at conveying expression through the bent posture of her body, than through facial expressions which are often blurred or ignored.

Similarly, you can’t help noticing that the early landscapes like the avenue of poplars, above, very much lack the suave painterly finish and style of his models (Constable, Millais).

But what happens as you transition into room four – which covers his move to Paris to be near his brother in 1885 – is a tremendous artistic and visual liberation, so that the very wonkiness and imperfections in his draughtmanship which were flaws in the earlier works, are somehow, magically, triumphantly, turned into strengths. The blockiness, the weakness of perspective, the lack of interest in strict visual accuracy, have suddenly been converted into a completely new way of seeing and of building up the image, which feels deeply, wonderfully emotionally expressive.

Sorrowing old man (‘At Eternity’s Gate’) by Vincent van Gogh (1890) © Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Room four makes fleeting reference to the community of like-minded artists he found working around Paris, and in particular to Pissarro, exponent of what was being called neo-Impressionism.

It seems quite obvious that van Gogh was very influenced by the Frenchman’s experiments with chunks and blocks, and spots and dabs and lines of pure colour. The painting above combines the strong formal outlines redolent of the black and white Victorian prints he revered so highly, with a new approach to filling in the outlines – not with a consistent smooth finish à la Millais – but a completely new idea of filling the space with disconnected lines of paint, the artist quite happy to leave blanks between them, quite happy to let us see them as isolated lines all indicating colour and texture.

The curators link this technique back to the cross-hatching used to create volume and shape by the Victorian print-makers and illustrators. So one way of thinking about what happened is that Vincent transferred a technique designed for print making to oil painting. What happens if you don’t create a smooth, finished all-over wash of colour, but deliberately use isolated lines and strokes, playing with the affect that basic, almost elemental short brushstrokes of mostly primal colours, create when placed next to each other.

It has a jazzy effect, creates a tremendous visual vibration and dynamism. the image looks like it is quivering or buzzing.

The Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition

To be honest, by this stage my head was buzzing with the fabulous images of Doré and Fildes and the other British illustrators, and van Gogh’s similarly social realist depictions of the poor, the old, prostitutes and so on and the way the early social realist paintings had morphed into a series of paintings of outdoor landscapes. I felt full to overflowing with information and beauty. But there was a lot more to come.

Suddenly it is 1910 and room five is devoted to the epoch-making exhibition held in London and titled Manet and the Post-Impressionists by the curator Roger Fry. As with Doré’s underground image at the start, the curators have blown up a page from a popular satirical magazine of the time, depicting the dazed response of sensible Britishers to the outlandish and demented art of these foreign Johnnies and their crazed, deformed, ridiculously over-coloured paintings. A number of Vincent’s paintings were included in the show and came in for special scorn from the philistine Brits.

This amusing room signals the start of part two of the show which looks at van Gogh’s posthumous influence on a whole range of native British artists.

This second half is, I think more mixed and of more questionable value than the first half. We know which British artists and illustrators van Gogh liked and admired and collected, because he included their names and his responses to their works, in his many letters.

As to the influence he had after his death, this is perforce far more scattered and questionable. Thus room six introduces us to paintings by Walter Sickert, leader of the Camden Town school (whose work I have always cordially hated for its dingily depressing dark brown murk), to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant (bright Bloomsburyites), and to Matthew Smith, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman.

It’s impossible to place any of these artists on the same level as Vincent. Amid the sea of so-so also-rans, the scattered examples of works by van Gogh ring out, shout from the walls, proclaim the immensity of his genius, the vibrancy of design, colour and execution. Like an adult among children.

That said, there’s quite a lot of pleasure to be had from savouring these less-well-known British artists for their own sakes. I was particularly drawn to the works of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore. Here is Gore’s painting of Gilman’s house. It doesn’t have a lot to do with van Gogh, does it, stylistically? Apart from being very brightly coloured.

Harold Gilman’s House at Letchworth, Hertfordshire by Spencer Gore. Courtesy of New Walk Museum & Art Gallery, Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Similarly, I really liked Gilman’s picture of the inside of a London caff, focusing on the decorative wallpaper and bright red newel posts, and a sensitive portrait titled Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table, 1917. The curators relate this latter painting back to Vincent’s vivid, warts-and-all portraits, which also contain highly decorative elements and stylised wallpaper, a garish brightness which scandalised critics of the 1910 show.

Maybe. It’s a good painting, he conveys the old woman’s character in a sober, unvarnished way and the use of decorative elements is interesting. But only a few yards away is hanging one of five or six drop-dead van Gogh masterpieces of the show, the Hospital at Saint-Rémy (1889), and there is absolutely no competition.

Good God, hardly anything you’ve ever seen before explodes with such power and vibrancy as this painting. The brown earth, the green grass, the writhing trees and the very air seem to have burst into flames, to be erupting and leaping with energy, fire, ecstasy, fear, manic force.

Although there are a number of other, milder, more discreet landscapes by Vincent, when he is in this manic mood he wipes everybody else off the table, he dominates the dancefloor, he takes over the room, while the others are playing nice tunes on their recorders, he is like a Beethoven symphony of colour and expression, full of tumult and vision.

The impact of sunflowers

Emotionally and intellectually exhausted? I was. But there’s more. A whole room devoted to sunflowers. Pride of place goes to one of his most famous paintings, the sunflowers of 1888, and I was fascinated to learn from the wall label that van Gogh’s still lifes contributed to a major revival of the art of painting flowers. There are ten or a dozen other paintings of sunflowers around this room, by a whole range of other artists (of whom I remember Winifred and William Nicholson, Christopher Wood and Frank Brangwyn and Jacob Epstein). One of the Brits is quoted as saying that the painting of flowers had been more or less dismissed by the moderns, as having come to a dead end in Victorian tweeness and sentimentality. Until Vincent’s flower paintings were exhibited in the 1920s.

Van Gogh’s flower works showed that flowers could be painted in an entirely new way, blazing with colour and passion, wildly undermining traditional canons of beauty, revealing the passionate secrets implicit in the shapes and patterns of nature.

In a work like this you see a pure example of his exploration of colour for its own sake, a post-Impressionists’ post-Impressionist, the sunflowers not only being a blistering depiction of the flower motif, but a highly sophisticated and daring experiment with all the different tones of yellow available to the artist in 1888. So much to do, so much to paint, so much experience implicit in every fragment of God’s beautiful world!

Van Gogh’s reputation between the wars

By the 1920s van Gogh’s works were being exhibited regularly in Britain and snapped up by private collectors. He became famous. The process was helped hugely by the publication in English translation of his vivid, passionate and tormented letters. The life and the works became inextricably intertwined in the myth of the tortured genius. The curators quote various writers and experts between the wars referring to Vincent’s ‘brilliant and unhappy genius’.

However, this room of his last works makes a simple point. For a long time it was thought that the painting he was working on when he shot himself on 27 July 1890 was ‘Wheatfield With Crows‘. Forests have been destroyed to provide the paper for oceans of black ink to be spilt publishing countless interpretations which read into this fierce and restless image the troubled thoughts which must have been going through the tormented genius’s mind on his last days.

Except that the display in this room says that the most recent research by Vincent scholars have conclusively proven that it was not Van Gogh’s last painting! The painting he was working on when he shot himself was a relatively bland and peaceful landscape painting of some old farm buildings.

The point is – there’s nothing remotely tormented about this image. And so the aim of the display is to debunk the myth of the ‘tortured’ artist and replace it with the sane and clear-eyed artist who was, however, plagued by mental illness.

Phantom of the road

This point is pushed home in the final room which examines van Gogh’s reputation in Britain after the Second World War. All his works, along with all other valuable art had been hidden during the war. Now it re-emerged into public display, including a big show at Tate in 1947.

In the post-war climate, in light of the Holocaust and the atom bomb, the legend of the tormented genius took on a new, darker intensity. The curators choose to exemplify this with a raft of blotchy, intense self-portraits by the likes of David Bomberg which, they argue, reference van Gogh’s own striking self portraits.

But this final room is dominated by a series of paintings made by the young Francis Bacon in which he deliberately copies the central motif of a self-portrait Vincent had made of himself, holding his paints and easel and walking down a road in Provence.

Bacon chose to re-interpret this image in a series of enormous and, to my mind, strikingly ugly paintings, three of which dominate one wall of this final room.

They are, in fact, interesting exercises in scale and colour, and also interesting for showing how Bacon hadn’t yet found his voice or brand. And interesting, along with the Bomberg et al in showing how the legend of tormented genius was interpreted in the grim grey era of Austerity Britain.

And they show what a very long journey we have come on – from the young man’s early enthusiasm for Charles Dickens and Gustave Doré right down to his reincarnation as a poster boy for the age of the H-bomb.

A bit shattered by the sheer range of historical connections and themes and ideas and visual languages on show, I strolled back through the exhibition towards its Victorian roots, stopping at interesting distractions on the way (some of Harold Gilman’s works, the big cartoon about the Post-Impressionist show, some Pissarros, the Millais and Constable at the beginning, the wall of Dorés), but in each room transfixed by the one or two blistering masterpieces by the great man.

Even if you didn’t read any of the wall labels or make the effort to understand all the connections, links and influences which the curators argue for, it is still worth paying to see the handful of staggering masterpieces which provide the spine for this wonderful, dazzling, life-enhancing exhibition.

Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh (1888) Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Photo © RMN-Grtand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski

Promotional video

Related links

- Van Gogh and Britain continues at Tate Britain until 11 August 2019