The curators think the American artist Philip Guston (1913 to 1980) was one of the most remarkable artists of the twentieth century. Usually I can see what they’re getting at, even if I don’t like an artist much, but this a rare occasion when I really didn’t get it at all.

On the evidence of this huge, major retrospective, which contains more than 100 paintings and drawings from across Guston’s 50-year career, it feels like he toyed with or experimented with a series of 20th century styles, never an innovator, seeming much more like a follower who did copied styles invented by other people, often very competently, until, in the late 60s, he had painted himself into a corner, had reached the end of road copying other people, and had a massive block, painting nothing for a couple of years.

When he re-emerged it was with a radically new style, because he had discovered cartoons. The curators call it ‘drawing’ and there’s plenty of drawings here, a roomful of the studies which got him back into the groove, but, in my opinion, all in a cartoon style, and certainly it eventuated in hundreds and hundreds of paintings which look like this.

‘Couple in Bed’ by Philip Guston (1977) The Art Institute of Chicago © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In this brief review I’ll reprise the shape of his career so you can judge for yourself.

Early years

He was the son of dirt poor Jewish immigrants, the Goldsteins, who had experienced antisemitic pogroms in the Ukraine, and then the tragic deaths of family members when they made it to America, crossing all the way over to Los Angeles to settle in 1922, when our guy was just 9 years old.

So he was raised in a hard-working, socially conscious, left-wing environment, with a particular sensitivity to racism of all forms (which was to come out, a lot later, in the form of a weird obsession with the white hooded figures of the Ku Klux Klan – see below).

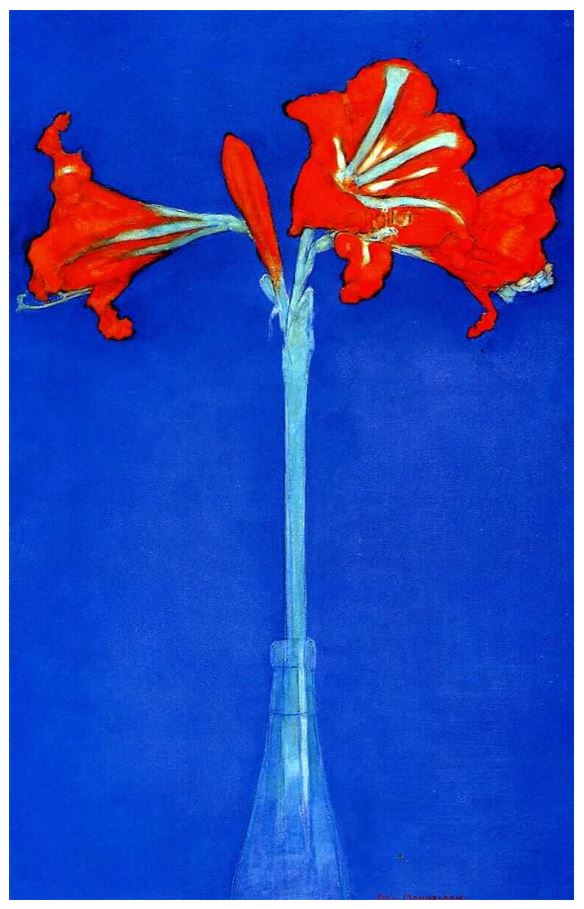

Picasso

His early works seem to me to straight copies of Picasso’s neo-classical 1920s style with some surrealism thrown in. Thus this woman seems Picasso while the stitched head or ball on top of the easel looks like de Chirico.

‘Female Nude with Easel’ by Philip Guston (1935) Private Collection © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

But he also did a completely different style of grubby, gritty, stylised but much more realistic portraits, including a powerful one of himself

The 1930s were a very political decade, and he was also drawn to the large-scale and very socially conscious mural art of the Mexican Diego Rivera. In fact Rivera helped Guston get a commission, alongside Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner, to create a large mural in Mexico in 1934.

The result, ‘The Struggle Against Terrorism’ (1934 to 1935) was later painted over by the Mexican authorities. Only recently has restoration work made it available again, and this exhibition features a massive video projection of it, highlighting its theme of the oppressive nature of the Mexican church.

Back in the States Goldstein changed his name to Guston, precisely to avoid a growing swell of antisemitism in America and moved to New York. Moving among artists and writers and intellectuals boosted his left-wing attitudes even more and led, among other works, to a defining work of the era, ‘Bombardment’ from 1937, which combines the clear sheets of colour from the classical Picasso with the large-scale composition of his mural approach and a popular (cartoony?) treatment.

‘Bombardment’ by Philip Guston (1937) Philadelphia Museum of Art © Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

1940s

Then came a massive change in his style. He began teaching at universities in lowa City and Saint Louis and turned away from public political art. He continued doing portraits (in their quiet way, maybe these are the best bits of the show). But, like so many of his generation, appalled by the trauma of the Second World War and the revelation of the Holocaust, he turned to increasingly abstract compositions. It was the birth of Abstract Expressionism and Guston chucked his old figurative style(s) and threw himself into the new way of seeing and working.

The exhibition has two rooms of his abstract expressionist paintings, one from the 1940s, then moving on to the 1950s and it seemed to me blindingly obvious that he got steadily worse. In the winter of 2016 the Royal Academy hosted a blockbuster exhibition of Abstract Expressionism and it came as a revelation; I was blown away; room after room of masterpieces; a revelation that paintings which don’t depict anything could be so varied and so exciting.

None of Guston’s abstract paintings did it for me. He hadn’t the excitement of Jackson Pollock, the meditative power of Mark Rothko, the dynamic patterning of Lee Krasner, or the stark drama of Clyfford Still. In my opinion the first room of Guston abstracts is bad and the second one is horrible.

‘Passage’ by Philip Guston (1957 to 1958) MFAH © Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth Photograph © MFAH / Will Michels

Nonetheless, he was, apparently, an influential figure in the New York School alongside his high school friend Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko.

Disillusion

As the gusty 1960s turned into the colourful 1960s, though, Guston got sick of painting in the same mode. For me, it really shows, his abstract paintings start off poor, become terrible, and then it feels like he gives up in disgust. The exhibition compensates for the poor quality of the art with a great deal about Guston’s political views. He was not, as you might have guessed, a big fan of the Vietnam War, but in fact it was the resurgence of racism back home in the states which really got to him.

Extras

The curators have done their best to make this a really defining, landmark exhibition of the full range of Guston’s work, along with all kinds of supporting material and documentation. The show is accompanied by commentary, stories, and personal reflections from Tate curators and guest contributors, including:

- the artist’s daughter Musa Mayer

- writer Olivia Laing

- art historian and curator Aindrea Emelife

- artist Charles Gaines

- Tate paintings conservator Anna Cooper

- illustrator and artist Blk Moodie Boi

- chef and family friend of Guston’s, Ruth Rogers

Also included in the exhibition are specially commissioned responses from musician Anja Ngozi and poet Andra Simons, inspired by Guston’s collaborative spirit.

In his 1950s abstract phase he was friends with avant-garde composers –John Cage, of course, everyone knew Cagey, but also Morton Feldman and one of the abstract rooms plays bits from the very long (four hours) piece by Feldman which the composer wrote specially for Guston. It is characteristically serialist or abstract, but quiet and lovely. I like Morton Feldman. As one of the commenters on YouTube says, it ‘sounds like an alien trying to make human music’, which is precisely the quality I like, away off the edge of something.

Blockage

A wall label tells us that in the late 60s Guston abandoned painting altogether for 18 months or so. But during that period he continued drawing and sketching obsessively, mainly the objects in his own apartment, tables and chairs and shelves and beds but above all, books.

Note the vertical black lines in the book, and lying around on the (invisible) table. Using these lines as decoration, to create space, to define objects, would become a signature trick of his final style. Because out of this drawing came a way out of the corner he’d painted himself into. He embraced figuratism again, but of a very, very simplified, reductive type. He expanded the drawings into paintings, and then suddenly found himself painting unstoppably. The dam had broken. His block was over. for the next ten years he would paint hundreds and hundreds of really big paintings all taking the new approach.

‘Painting, Smoking, Eating’ by Philip Guston 1973) Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam © The Estate of Philip Guston

Note several things. The colour is pink, pinks and reds, a worrying shade of pink skin, pink flesh, a world of burned or flayed human skin. Then the dotted lines, like the nails in hobnailed boots. Are those boots piled up behind the bed? Certainly the use of dots and dashes to fill and decorate objects became a signature.

The Ku Klux Klan

The Klan was a symbol of evil racism for the young Guston. Now in the era of the Vietnam War, of the ferocious racist pushback against the Civil Rights Movement, and the tide of violence sweeping across America, they make a startling reappearance in Guston’s work, as disturbing cartoon emblems of the banality and ludicrousness of evil.

So: 1) pink, very pink, buildings, sky, road all shades of pink, so a kind of abstraction. 2) The obviously ‘naive’, untrained, outsider cartoon style. 3) Those lines of dashes, giving definition to everything from the windows in the skyscraper, the wheels of the car (or tractor?), the eyeslits of the Klansmen, and the odd dotted lines on the back of their hoods.

In 1970 Guston showed 30 of these works at a now infamous show at New York’s Marlborough Gallery. Almost all the critics and his friends were appalled. Abstract Expressionism was closely connected with an immensely serious, ‘committed’ attitude to life and art and politics, a tragic worldview mixed up with European existentialism.

All of that had (apparently) been chucked out in the name of what most critics thought a disastrous turn to a naive, crudely cartoony style. But Guston persisted, and the last four rooms of this huge exhibition are stuffed with scores of examples of the same approach applied again and again.

Many of them are depictions of interiors but coloured with a kind of naive surrealism, giant eyes, mountains of legs, abandoned shoes, and everyday objects rendered both familiar and strange. There’s a lot of him or some human being in bed, like ‘Couple in Bed’ that I opened with.

I found that once you’d assimilated the approach, the pink worldview with dots and dashes, men in pointy hats, other men curled up in bed, er, there wasn’t much more to take in. To try and be positive, there’s no doubting that he had finally created a signature style – his early works seem to me straight copies of Picasso, de Chirico-style surrealism, Rivera-style social murals, and then Pollock and Rothko abstraction. In all of them he seems, to me, a follower. Here, though, in his last fertile decade, he emerges as utterly original and distinctive. I can see that much, and I managed to like some of the images, the best of them, but most of the ones in these four big rooms left me indifferent.

The last room contains one of the best uses of his new style which has, justifiably, been chosen as the poster and promotional image. On its own it looks great. Set amid 30 or so other very similar images in a closely related palette and style, not so much.

If you’re anywhere near Tate Modern and fancy an exhibition, I wouldn’t go and see this – see the outstanding exhibition of African photography, instead.

Related links

- Philip Guston continues at Tate Modern until 25 February 2024

- Exhibition guide