‘Nature or, that which I see, inspires me, puts me, as with any painter, in an emotional state so that an urge comes about to make something, but I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that…’

(Piet Mondrian, 1914)

‘The more we discover the wonders of nature, the more we become aware of ourselves.’

(Hilma af Klint, 1917)

Mondrian is obviously one of the masters of modern art; most educated people would immediately recognise one of his characteristic abstract paintings. By contrast, Hilma af Klint is a lot less well-known. What they have in common, though, was that they both journeyed from late-Victorian figurative i.e. realistic art, to abstraction, albeit completely different styles of abstraction. And, as with so many pioneers of abstraction, they developed their modern abstract styles in response to surprisingly old-fashioned spiritual motivations, to deeply-held mystical and Theosophical beliefs about Nature and Truth which this excellent exhibition explores in great detail.

I didn’t expect to like this exhibition that much and, from the publicity photos had taken a little against af Klint. How wrong I was! This is a brilliant exhibition – af Klint emerges as a huge artist in her own right – and, above all, I had no idea that two artists could have produced such a range and variety of styles. There are so many different types of painting to savour and enjoy.

Landscape painters

Hilma af Klint (1862 to 1944) and Piet Mondrian (1872 to 1944) began their careers as academically trained landscape painters in the late nineteenth century, before developing radically new models of painting in the twentieth century. Although they did not know each other – or of the other’s work – the exhibition shows how they began their careers very firmly rooted in naturalistic depictions of the natural world, and how they slowly, steadily took different but parallel paths away from these roots to arrive at highly stylised abstraction.

Flowers and trees

Both artists spent a lot of time painting flowers. Room three devotes a whole wall to displaying 20 wonderfully accurate botanical watercolours done by af Klint, the kind of thing which still illustrates guides to wildflowers I’ve bought recently.

Marvellous, isn’t it? A whole wall of lovely paintings of buttercups, nasturtiums, stonecrop, thistle, saxifrage, apple blossom and many more. I wanted to buy the entire wall and take it home with me.

Installation view of ‘Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian’ at Tate Modern, showing the wall of botanical paintings by af Klint (photo by the author)

On the opposite wall are 15 flower paintings by Mondrian which are more full-bodied and intense. According to the curators:

Many of these paintings and drawings of flowers that Mondrian made in 1908 to 1909 are full of symbolism, mainly relating to Theosophy. Shortly afterwards, he moved away from symbolist representations, but continued to portray flowers until his death, selling them for income at times of financial difficulty. He repeatedly returned to the same varieties, such as chrysanthemums and arum lilies.

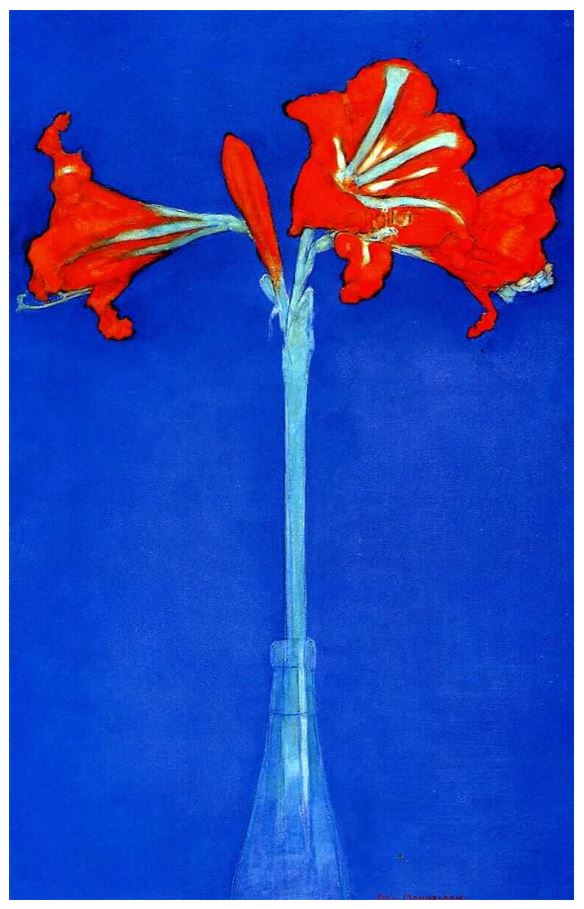

Some of these are really standout pieces. Take this stunning amaryllis.

After staring at it for some time I realised I really liked the depiction of the bottle the flower is standing, a beautifully pure and evocative rendition, almost a piece of 1960s Pop Art.

The Ether

During their careers, new technologies such as the microscope, X-ray radiography and photography were challenging human perception. The evidence of worlds invisible to the human eye catalysed shifts across science, spirituality and the arts. These discoveries in the sciences meshed with slightly earlier schools of thought, especially the theories of Theosophy. The Theosophy Society was founded in 1875 its chief thinker, Helena Blavatsky, published works developing the theory during the 1880s and 90s.

The exhibition devotes an entire room to exploring various aspects of Theosophical belief and its impact on our two artists, and it wasn’t a peripheral impact: in 1904, af Klint joined the Stockholm lodge of the Theosophical Society and Mondrian Amsterdam Lodge in 1909. A central belief, which meshed with the science of the time, was that all living things are connected by an invisible, imperceiveable force, which they called ‘the ether’, and that’s why this gallery has been called The Ether.

One among many aspects of this was an anthropomorphised version of Darwin’s theory of evolution which lent it a spiritual aspect, optimistically hoping that all life forms were evolving and yearning towards higher spiritual truths. Hence af Klint’s series titled ‘Evolution’. Here you can see how zoomorphic shapes and botanical motifs have been simplified and stylised to form the basis of complex but abstract designs.

‘The Evolution, The WUS/Seven-Pointed Star Series, Group VI, Number 15’ by Hilma af Klint (1908) Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

This spiritualised version of evolution attracted many writers, artists and thinkers at the turn of the century. The Great War had yet to dent, or demolish, people’s romantic faith in progress and improvement. Mondrian gave the title to a strikingly different kind of work, one depicting three highly stylised female forms.

Mondrian wrote of this painting: ‘It’s not so bad, but I’m not there yet.’ The figures represent the stages in evolution from the physical to the spiritual realm, as promoted in Theosophy. The triangular nipples and navels of the women, which point upwards and downwards, symbolise their spiritual and earthly orientation. The central figure embodies the fulfilment of the evolutionary process, to the spiritual realm. The flowers on the left panel are symbols of purity, while those on the right symbolise tragic suffering.

Incidentally, among many other treasures in the Ether Room is the surprising inclusion of four small paintings by the famous psychotherapist and guru Carl Jung. To quote the curators:

Carl Jung’s Liber Novus is now known as ‘The Red Book’, due to the colour of its cover. It is not certain that he ever intended to publish this account and interpretation of his years of personal crisis between 1913 and 1916. The book is full of illustrations combining symbols from various religions, such as mandalas and trees encased in egg-like forms that resonate with af Klint’s work. It is regarded as the seed of the analytical psychology Jung would later develop, in which the conscious and unconscious are assimilated into the whole personality.

The four works by Jung are surprisingly powerful and certainly fit right in, in this context.

Abstraction 1. The impact of cubism

How did Mondrian arrive at his final style? In stages. He travelled to Paris in 1911 and was immediately galvanised by cubism which he reinterpreted with a spiritualist slant. He began reworking drawings and paintings of trees in the new style. the catalogue has a nifty quote from Guillaume Apollinaire assessing a small show of Mondrian’s drawing attention to the obvious cubist influence, but cannily predicting that Mondrian was using it for other ends and would probably develop his own version.

There are many cubist-era works by Mondrian on show. Here you can see cubism hitting his naturalistic depictions of flowers and trees like a freight train, taking it somewhere completely new.

The exhibition includes examples of the many interim steps, fascinating and often beguiling abstracts in their own right, which move towards this, six years later, in the midst of the Great War, when the discrete elements of the earlier paintings have become solidified into blocks, blocks of abstract colour, floating against an empty background (or a background flooded with invisible ether, which joins the disparate entities?)

‘Composition in colour B’ by Piet Mondrian (1917) Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Abstraction 2. Mondrian reaches his mature style

‘By the unification of architecture, sculpture and painting a new plastic reality will be created.’ (Piet Mondrian, 1917)

Around 1920 everything came together in the new style of rectangular grids separated by thick straight black lines, a visual language of ‘pure relationships’ which he called ‘neo-plasticism’. These paintings abandoned any form of symbolism as they become irregular grids. He set out to reduce painting to its basic principles, removing individual aspects (which he called ‘tragic’) to express the ‘universal’.

In 1921 he published an essay titled ‘Le Néo-Plasticisme: Principe général de l’équivalence plastique’ which explains neo-plasticism as an approach to representing the ‘universal’ through balancing oppositions of the most basic elements of painting: position, size and colour.

Mondrian believed that neo-plastic principles were destined to define the world around us. Some critics described the paintings as having ‘jazz rhythms’ and I’ve seen modern jazz album covers with Mondrians on them, both of them expressing something about the clean pure and yet somehow dynamic lines of modernity. The Tate bookshop includes ‘The Afterlife of Piet Mondrian’ by Nancy Troy which looks interesting, an examination of how the Mondrian style was curated, copied and publicised, of how ‘the popular appeal of Mondrian’s instantly recognizable style in fashion, graphic design, and a vast array of consumer commodities’.

One room is devoted to Mondrian’s mature style and there’s a very noticeable difference between the works from the 1920s and 30s. In both the works from the 1920s, not all the lines extend to the very edge of the canvas. Petty detail though this may seem, it makes a lot of difference, because in the next space are three classic Mondrians from the 1930s and in each instance the black lines do extend all the way to the edge. Trivial though it sounds, they look more complete, more finished, more total.

It’s a mystery to me and something the curators don’t address which is how come such rigid geometric shapes are so very pleasing to the eye and mind. they feel calming, deep, completing in a way which is hard to convey. Mondrian himself commented:

‘Vertical and horizontal lines are the expression of two opposing forces; they exist everywhere and dominate everything; their reciprocal action constitutes “life”. I recognised that the equilibrium of any particular aspect of nature rests on the equivalence of its opposites.’ (Piet Mondrian, 1937)

Not sure that helps explain why this look immediately struck everyone as clean and classic and has remained so for 80 years.

Abstraction 3. The Ten Largest

‘My mission, if it succeeds, is of great significance to humankind. For I am able to describe the path of the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.’ (Hilma af Klint, 1917)

I thought the climax of Mondrian’s development in those three classic works from the 1930s, presented in a clean white rectangular space, would be difficult, but in the event the curators completely trump them with the last room in the exhibition. This is devoted to a set of ten enormous, huge and overwhelming canvases by af Klint, titled ‘The Ten Largest’.

The Ten Largest, Group IV, Number 7, Adulthood by Hilma af Klint (1907) Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

These ten huge paintings represent the stages of life, with two each representing Childhood, two devoted to Youth, four to Adulthood, and the final pair to Old Age. I thought I wouldn’t like these at all but, somehow, the preceding nine rooms, showing the slow development of her style, explaining the mystical and spiritual beliefs behind it, had softened me up and prepared me. I thought they were magnificent.

The Ten Largest, Group IV, Number 3, Youth by Hilma af Klint (1907) Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

‘The Ten Largest’ are part of ‘The Paintings for The Temple’, a body of works af Klint believed was commissioned by her spiritual guides (we have learned about her spiritual guides throughout the show). Af Klint dreamed of building a temple in the form of a spiral where her paintings could be hung together as a ‘beautiful wall covering’. To ascend through the temple would mean moving towards a higher state of being.

Installation view of ‘Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life’ at Tate Modern showing two of the four Adulthood works. Photo: Tate (Jai Monaghan)

It took me a while to realise that the four ages are colour coded: the Childhood pair have a lovely deep blue background, the two Childhood works have an orange background, the four Adulthood paintings the lilac colour you can see in the photo above, and the final Old Age pair have a pink background. Then I realised that the colour in each set fades and becomes paler in the second or later work in each set, as if that era’s virility fades as it prepares to transmute to the next stage of life. None of that, none of the richness or intensity of the colour, and the dramatic sense of their changing hues, comes over in these photographs.

Installation view of ‘Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life’ at Tate Modern showing, from left to right, the second Childhood (blue), the two Youth (orange) and the four Adulthood (lilac) paintings. Photo: Tate (Jai Monaghan)

As you can see each painting consists of arrangements of completely abstract designs and patterns and yet, slowly, as you study them, you realise certain motifs recur in each set, giving them a thematic unity.

I spent a lot of time wondering why the final two paintings, the Old Age set, were the ones with the most conspicuous use of symmetry. Is it because, after the storms of life, your knowledge settles into a balanced wisdom?

And the even more puzzling fact that the very last painting is the only one to contain a square or rectangular feature, namely a grid of squares like a chessboard. Is it because the swirling zoomorphic shapes of active life give way, in one’s last years, to a harder, adamantine, inflexible knowledge?

The Ten Largest, Group IV, Number 10, Old Age by Hilma af Klint (1907) Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Almost certainly not, but I was beguiled. I found myself walking round, sitting and staring, getting up and reviewing them slowly, again and again. I couldn’t tear myself away, an experience I’ve had with only a few other exhibitions – I remember not wanting to leave a room full of Monet paintings of the River Thames years ago. Same here. I found this final room completely absorbing, entrancing and didn’t want to leave.

There’s lots and lots of lovely paintings, in an amazingly wide range of styles, sizes, and intentions, throughout this wonderful show. But this final room is worth the admission price by itself.

The video

Related links

- Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian continues at Tate Modern until 3 September 2023

- Exhibition guide

- Large print guide i.e. all the wall captions

- Focus on Hilma Af Klint

- Who is Piet Mondrian