The greatest fortune a man can have is to conquer his enemy, steal his riches, ride his horses, and enjoy his women.

(Genghis Khan)

Genghis Khan was born sometime in the 1160s into a small clan of Steppe Mongols. From obscure origins he rose, through the power of his charisma, courage and canny alliances, to unite the disparate Mongol tribes into one huge, well-organised, ferocious and world-beating army.

By the time of his death in 1227 Genghis had subjugated more lands and more people in twenty-five years than the Romans did in four hundred. His successors built on his conquests until the empire he bequeathed stretched from Hungary in the west to the Pacific in the East, forming the largest continuous land empire the world has ever known.

James Chambers’s biography is a small, zippy book, part of the Sutton Pocket Biography series, designed, in their words, to be ‘highly readable brief lives of those who have played a significant part in history, and whose contributions still influence contemporary culture.’

At 100 small pages it’s a quick read – it only took me two hours to wing through it. But what makes this book different from most of the other biographies of Genghis is its distinctive approach: it starts out in the fairy tale tones of Mongol myth and legend, and never really quite transitions to the dry, factual approach most of us associate with normal ‘history’. Which makes it rather marvellous.

Thus Chambers starts his text without any introduction or explanation but by going straight into a retelling of the creation myth of the steppe Mongols. He tells us how the god of Eternal Heaven, Mongke Tengri, made all things, but humans didn’t appear until the grey wolf, the grey hunter, wandered down from his mountain and mated with a deer.

Detail of a Totem from Northern Mongolia showing a grey wolf and a white doe (Hun tomb, 3rd to 1st century BC). Born according to the will of the Sky, Borte Chino (Blue Wolf) is the ancestor of the Mongolians and his partner/wife is Gua Maral (Red Deer)

The story then skips forward ten generations to when the Mongols have bred and multiplied, and a direct descendant of the grey wolf’s firstborn, Dobun the Sagacious, marries a woman named Alan the Fair, who came from a tribe of hunters in the forest.

We learn how Alan had five sons and taught them to stick together but, after her death, the four eldest divided her herd between them and left the youngest, Bodunchar the Simple, to ride off alone on an ugly pony. When they repented of their meanness and went to find him, they discovered Bodunchar living in a hut on the banks of the river Onon and surviving by hunting duck with a trained hawk and begging mare’s milk from a clan camped nearby.

Once they’d taken Bodunchar back into the family, he tells them more about the nearby clan who’d helped him out, namely that they lack central organisation or a strong leader. And so the five sons of Alan the Fair proceed to attack the clan, stealing all their cattle and their women.

By the standard of the steppes there was nothing wrong in what Bodunchar and his brothers had done. In truth, as well as in legend, it was the way in which Turko-Mongol nomads had always lived, and the way in which they were to continue to live for several more generations. These nomads measured each other’s wealth by the numbers of their sheep and horses, and when the size of a clan’s herds increased, it was usually as a result of audacious raiding rather than patient husbandry. Ruthless opportunists like Bodunchar were regarded as heroes, and their success bred success. Warriors often moved from clan to clan, swearing new allegiances to the men most likely to protect their families and make them rich. Although the tribes and clans into which they were divided must have begun as extended families, their blood lines were soon diluted, not only because those with the best leaders attracted warriors from elsewhere, but also because it was the custom to marry outside the clan. Since bride prices were high, women were often acquired like horses on raiding parties. In such a society life was simple, selfish and precarious. (p.5)

Why are we being told all these stories about Alan the Fair and Bodunchar the Simple? Because shamans, the Mongol holy men, had prophesied that a descendant of Bonduchar would unite all the Mongol tribes and lead them to world conquest.

And so it is that, several generations later, a boy is born of Bonduchar’s line, a boy named Temüjin, one of the five children of Yesügei. In preparation, Chambers has described the confused and war-torn world Temüjin grew up in:

- how the great city of Zhongdu (early Beijing) had been captured by Khitan horsemen from the steppes

- how the Chinese Song empire had been weakened when the Tangut inhabitants of north-west China seceded to establish their own kingdom of Xi Xia

- how the north had been wrested from the Khitan by a new wave of conquerors, the Jurchen who came from Manchuria and established a new dynasty they called the Jin

- how the Jin feared invasion by other Mongol tribes and so allied with Tatar tribes who they paid to attack and break up the remaining Mongol forces

- how one of the Mongol commanders who survived these attacks was Yesügei, of the Kiyat clan, who claimed descent from Bonduchar

- and how Yesügei, after kidnapping himself a wife – Ho’elun of the Onggirats – from a prince of the Merkits, had five children by her, one of whom was Temüjin – Mongol for ‘man of iron’

- and how, aged just nine, Temüjin, lost his father Yesügei, poisoned by the tribe whose woman he stole to make his wife and Temüjin’s mother

And it was this Temüjin who would grow up to become Genghis Khan, one of the greatest, most successful but also most bloodthirsty conquerors of all time.

(NB Genghis Khan is an honorary name Temüjin was given after he had united the Mongol tribes, at the ripe age of 39. He was awarded it at a great assembly of all the Mongol tribes and clans, the Great Khuriltai held beneath the sacred mountain at the source of the river Onon in 1206 – Khan being the generic name for king or leader, and Genghis (probably) stemming from tengiz meaning ocean and so suggesting ‘King of Everything within the great ocean’ or ‘Oceanic King’, p.50).

The actual story of his rise to power is long and complex, mainly revolving around a sequence of alliances, at first with individuals who help or rescue young Temüjin from perilous situations (like Sorkun who helped Temüjin escape after he’d been captured and tied to a wooden yoke by the vengeful relatives of the first husband of Ho’elun, his mother, the woman kidnapped by his father Yesugei), then with more powerful clan leaders, slowly cultivating powerful men and drawing freelance warriors to his side.

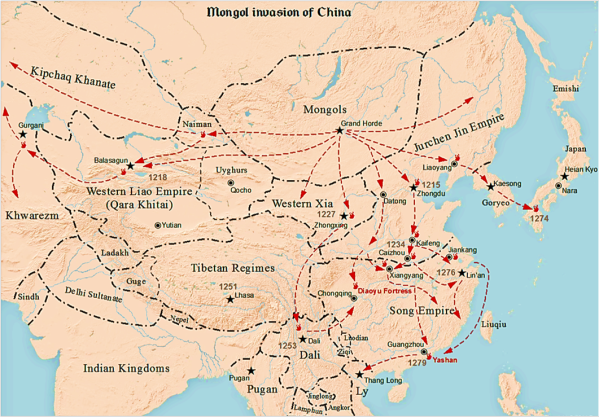

Map of the Mongol Empire during Genghis’s lifetime, showing the complexity of the Mongol tribes and kingdoms he set out to unify, and the peoples living outside it e.g. the Chinese Jin Dynasty in the south-east (Source: Wikipedia)

And then the thing which set him apart from all his rival leaders and rival powers – his phenomenal gift for organisation, for imposing new laws on the Mongol tribes, for introducing a census and mass conscription, for organising his army into light and heavy cavalry with, later on, divisions devoted to siege equipment, provisioned with scaling ladders and sacks that could be turned into sandbags (p.72).

His army was systematically organised and rigorously disciplined. A division was known as a tumen and contained 10,000 men. Each tumen was divided into ten regiments of a thousand called a minghan. Each minghan contained ten squadrons of a hundred called a jagun and each jagunwas divided into ten troops called arbans. A large Mongol camp was called an ordu which is the origin of the English word ‘horde’.

Chambers goes on to describe the thorough training regime Genghis established for the army, along with the ‘staff college’ of his personal guard, which supplied the generals and senior commanders to each division. He explains the Mongols’ battle tactics and the transmission of information by a cohort of trained messengers using the fastest horses. Genghis set up staging posts every 25 miles in the territory he conquered, which were permanently manned with provisions and fresh horses, so that messengers could ride in relay in any direction across his empire bringing vital information. The messengers were wrapped up warm and wore a belt of small bells to alert the managers of the post that a rider was arriving, so the new horse could be saddled and ready.

The essence of Genghis Khan’s genius lay in his ability to recognise and develop a good idea, and above all in his instinctive capacity for meticulous planning and detailed organisation, a capacity which was all the more extraordinary in a man who had received no education. (p.65)

Map showing the campaigns of the Mongols from their heartland out across Asia. Note that China was divided under three rulers, the Jurchen Jin in the North, the Song dynasty in the south, and the Western Xia in the space between Tibet and Mongolia (source: Wikipedia)

Now a glance at Amazon shows you that there are quite a few books about Genghis Khan, some running to four or five hundred pages, and there is, of course, a lengthy Wikipedia article about him.

But most of these are westernised, factual accounts, which start in the way you’d expect, with factual accounts of the steppe, its peoples, their history, before moving on to give factual accounts based on a judicial analysis of the sources and the (scant) archaeological evidence.

In some of these more academic respects Chambers’ account is a bit lacking; I certainly found his description of the campaigns of the mature Genghis rather quick and difficult to follow.

But it matters not. I bet this is the only account which starts and then continues within the Mongol mindset. It takes the reader inside the world of mare’s milk and hawking, surviving off berries and raw fish, a world where an extended family possesses just nine horses and a tent set amid the vast limitless blankness of the steppe. A world where the wolf god mates with human women, and shamans correctly predict the future.

Admittedly, as Chambers’ account proceeds and actually gets onto the campaigning and battles, it becomes more and more factual, more like Wikipedia, and my interest waned a bit. It also describes the military massacres which occurred on a growing scale and made Genghis’s name a terror to future generations.

Notable among these were the rape of Zhongdu, an early name for what is now Beijing. It was already an enormous city, with a population of maybe a million, protected by a huge wall. After a prolonged siege, the Mongols finally breached the wall in 1215. Genghis ordered total annihilation and for one month the conquerors burned, murdered and raped. A year later visiting ambassadors described the streets as slippery with human fat. And they were shown a white hill outside the ruined city walls which was made out of human skulls. (This forced the Jin ruler, Emperor Xuanzong, to move his capital south to Kaifeng and abandon the northern half of his empire to the Mongols. Further Mongol campaigns were to lead to the collapse of the Jin dynasty in 1234.) It was the same year that the Magna Carta was signed in England.

Even worse was the prolonged campaign against Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, Shah of the Khwarezmian Empire from 1200 to 1220. Muhammad made the very unwise move of arresting and executing the envoys that Genghis had sent to him. This prompted the Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia, which resulted in its utter destruction. The Mongols razed every city they came to and massacred every single inhabitant: the lowest contemporary estimates were 700,000 dead for each of the cities of Merv and Balkh, and a million and a half each for Herat and Nishapur, where the heads of men, women and children were gathered into separate piles. These are widely considered the bloodiest massacres the world had seen until the 20th century.

‘I am the punishment of God…If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.’ (Genghis Khan)

All this may well be true, but it’s another reason for finding the later part of the book less enjoyable.

Because my imagination had been so fired up by the opening, mythical chapters, and the way they wonderfully transport the reader into a genuinely remote and different other-world. These passages engrossed me like a children’s book does. It made me feel it was me fighting alongside Jebe the Arrow and Toghril the mighty, in a heroic alliance with the Naimans and the Tayichi’uts against enemy tribes like the Keraits and the Tatars, taking part in legendary conflicts like the wonderfully named Battle of the Seventy Felt Cloaks.

Reviews suggest that this short books leaves out a lot of the facts about Genghis, as known by modern historians. No doubt it does. But what it leaves in is the romance and fairy-tale feel of the wonderfully evocative names, the distant lifestyles, and the legendary stories about strange peoples and faraway places which for a happy couple of hours really caught my imagination.