Willett was born in 1917. He attended Winchester public school and then Christ Church, Oxford (the grandest and poshest of all the Oxford colleges). He was just beginning a career in set design when the Second World War came along. He served in British Intelligence. After the war he worked at the Manchester Guardian, before becoming assistant to the editor of the Times Literary Supplement, writing scores of reviews and articles, until he went freelance in 1967.

He had travelled to Germany just before the war and become fascinated by its culture. He met and befriended Bertolt Brecht whose plays he later translated into English. As a freelance writer Willett authored two books about the Weimar period. This is the first of the pair, published by the well-known art publisher Thames and Hudson. Like most T&H art books it has the advantage of lots of illustrations (216 in this case) and the disadvantage that most of them (in this case, all of them) are in black and white.

The New Sobriety is divided into 22 shortish chapters, followed by a 30-page-long, highly detailed Chronological Table, and a shorter bibliography. There’s also a couple of stylish one-page diagrams showing the interconnection of all the arts across Europe during the period.

Several points:

- Though it has ‘Weimar’ in the title, the text is only partly about the Weimar Republic. It also contains lots about art in revolutionary Russia, as well as Switzerland and France. At this point you realise that the title says the Weimar Period.

- The period covered is given as starting in 1917, but that’s not strictly true: the early chapters start with Expressionism and Fauvism and Futurism which were all established before 1910, followed by a section dealing with the original Swiss Dada, which started around 1915.

Cool and left wing

The real point to make about this book is that it reflects Willett’s own interest in the avant-garde movements all across Europe of the period, and especially in the politically committed ones. At several points he claims that all the different trends come together into a kind of Gestalt, to form the promise of a new ‘civilisation’.

It was during the second half of the 1920s that the threads which we have followed were drawn together to form something very like a new civilisation… (p.95)

The core of the book is a fantastically detailed account of the cross-fertilisation of trends in fine art, theatre, photography, graphic design, film and architecture between the Soviet Union and Weimar Germany.

In the introduction Willett confesses that he would love to see a really thorough study which related the arts to the main political and philosophical and cultural ideas of the era, but that he personally is not capable of it (p.11). Instead, his book will be:

a largely personal attempt to make sense of those mid-European works of art, in many fields and media, which came into being between the end of the First War and the start of Hitler’s dictatorship in 1933. It is neither an art-historical study of movements and artistic innovations, nor a general cultural history of the Weimar Republic, but a more selective account which picks up on those aspects of the period which the writer feels to be at once the most original and the most clearly interrelated, and tries to see how and why they came about. (p.10)

‘Selective’ and ‘interrelated’ – they’re the key ideas.

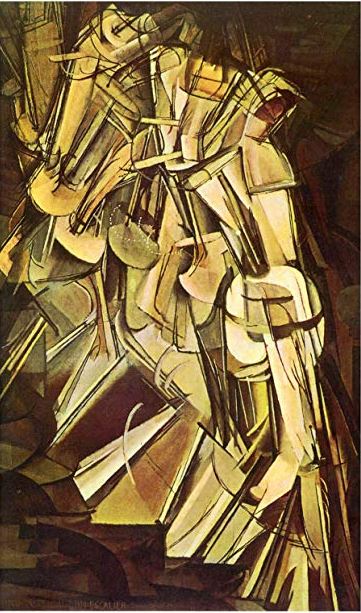

When I was a student I loved this book because it opened my eyes to the extraordinary range of new avant-garde movements of the period: Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Constructivism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, and then the burst of new ideas in theatre, graphic design, magazines, poetry and architecture which are still influential to this day.

Although Willett doesn’t come across as particularly left wing himself, the focus on the ‘radical’ innovations of Brecht and Piscator in Germany, or of Proletkult and Agitprop in Soviet Russia, give the whole book a fashionable, cool, left-wing vibe. And if you don’t know much about the period it is an eye-opening experience.

But now, as a middle-aged man, I have all kinds of reservations.

1. Willett’s account is biased and partial

As long as you remember that it is a ‘personal’ view, deliberately bringing together the most avant-garde artists of the time and showing the extraordinary interconnectedness (directors, playwrights, film-makers travelling back and forth between Germany and Russia, bringing with them new books, new magazines, new ideas) it is fine. But it isn’t the whole story. I’m glad I read Walter Laqueur’s account of Weimar culture just before this, because Laqueur’s account is much more complete and more balanced.

For example, Laqueur’s book included a lot about the right-wing thought of the period. It’s not that I’m sympathetic to those beliefs, but that otherwise the rise of Hitler seems inexplicable, like a tsunami coming out of nowhere. Laqueur’s book makes it very clear that all kinds of cultural and intellectual strongholds never ceased to be nationalistic, militaristic, anti-democratic and anti-the Weimar Republic.

Laqueur’s book also plays to my middle-aged and realistic (or tired and jaundiced) opinion that all these fancy left-wing experiments in theatre (in particular), the arty provocations by Dada, the experimental films and so on, were in fact only ever seen by a vanishingly small percentage of the population, and most of them were (ironically) wealthy and bourgeois enough to afford theatre tickets or know about avant-garde art exhibitions.

Laqueur makes the common-sense point that a lot of the books, plays and films which really characterise the period were the popular, accessible works which sold well at the time but have mostly sunk into oblivion. It’s only in retrospect and fired up by the political radicalism of the 1960s, that latterday academics and historians select from the wide range of intellectual and artistic activity of the period those strands which appeal to them in a more modern context.

2. Willett’s modernism versus Art Deco and Surrealism

You realise how selective and partial his point of view is on the rare occasions when the wider world intrudes. Because of Willett’s compelling enthusiasm for ‘the impersonal utilitarian design’ of the Bauhaus or Russian collectivism, because of his praise of Gropius or Le Corbusier, it is easy to forget that all these ideas were in a notable minority during the period.

Thus it came as a genuine shock to me when Willett devotes half a chapter to slagging off Art Deco and Surrealism, because I’d almost forgotten they existed during this period, so narrow is his focus.

It is amusing, and significant, how much he despises both of them. The chapter (18) is called ‘Retrograde symptoms: modishness in France’ and goes on to describe the ‘capitulation and compromise’ of the French avant-garde in the mid-1920s. 1925 in particular was ‘a year of retreat all down the line’, epitomised by the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes exhibition which gave its name to the style of applied arts of the period, Art Deco.

Willett is disgusted that dressmakers sat on the selecting committees ‘alongside obscure establishment architects and rubbishy artists like Jean-Gabriel Domergue’. Not a single German artist or designer was featured (it was a patriotic French affair after all) and Theo van Doesberg’s avant-garde movement, de Stijl, was not even represented in the Dutch stand.

Willet hates all this soft luxury Frenchy stuff, this ‘wishy-washy extremely mondain setting’ which was the milieu of gifted amateurs and dilettantes. It was a hateful commercialisation of cubism and fauvism, it was skin-deep modernism.

What took place here was a diffusing of the modern movement for the benefit not of the less well-off but of the luxury consumer. (p.170)

It’s only because I happen to have recently read Andrew Duncan’s encyclopedic book about Art Deco that I know that there was a vast, a truly huge world of visual arts completely separate from the avant-garde Willett is championing – a world of architects, designers and craftsmen who built buildings, designed the interiors of shops and homes, created fixtures and fittings, lamps and tables and chairs and beds and curtains and wallpapers, all in the luxury, colourful style we now refer to as Art Deco.

Thousands of people bought the stylish originals and millions of people bought the affordable copies of all kinds of objects in this style.

So who is right?

When I was a student I also was on the side of the radical left, excited by Willett’s portrait of a world of hard-headed, functional design in homes and household goods, of agit-prop theatre and experimental film, all designed to mobilise the workers to overthrow the ruling classes and create a perfect world. Indeed the same chapter which dismisses French culture and opens with photos of elegantly-titled French aristocratic connoisseurs and patrons, ends with a photo of a parade by the Communist Roterfront in 1926. That’s the real people, you see, that’s real commitment for you!

But therein lies the rub. The radical, anti-traditionalist, anti-bourgeois, up-the-workers movement in architecture, design, film and theatre which Willett loves did not usher in a new workers’ paradise, a new age of peace and equality – the exact opposite.

The sustained left-wing attacks on the status quo in Germany had the net effect of helping to undermine the Weimar Republic and making the advent of Hitler easier. All the funky film innovations of Eisenstein and the theatrical novelties of Meyerhold failed to create an educated, informed and critical working class in Russia, failed to establish new standards of political and social discourse – instead the extreme cliquishness of its exponents made it all the easier to round them up and control (or just execute) them, as Stalin slowly accumulated power from 1928 onwards.

Older and a bit less naive than I used to be, I am also more relaxed about political ‘commitment’. I have learned what I consider to be the big lesson in life which is that – There are a lot of people in the world. Which means a lot of people who disagree – profoundly and completely disagree – with your own beliefs, ideas and convictions. Disagree with everything you and all your friends and your favourite magazines and newspapers and TV shows and movies think. And that they have as much right to live and think and talk and meet and discuss their stuff, as you do. And so democracy is the permanently messy, impure task of creating a public, political, cultural and artistic space in which all kinds of beliefs and ideas can rub along.

Willett exemplifies what I take to be the central idea of Modernism: that there is only one narrative, one avant-garde, one movement: you have to be on the bus. He identifies his Weimar Germany-Soviet Russia axis as the movement. The French weren’t signed up to it. So he despises the French.

But we now, in 2018, live in a thoroughly post-Modernist world and the best explanation I’ve heard of the difference between modernism and post-modernism is that, in the latter, we no longer believe there is only one narrative, One Movement which you simply must, must, must belong to. There are thousands of movements. There are all types of music, looks, fashions and lifestyles.

Willett’s division of the cultural world of the 1920s into Modernist (his Bauhaus-Constructivist heroes) versus the Rest (wishy-washy, degenerate French fashion) itself seems part of the problem. It’s the same insistence on binary extremes which underlay the mentality of a Hitler or a Stalin (either you are for the Great Leader or against him). And it was the same need to push political opinions and movements to extremes which undermined the centre and led to dictatorship.

By contrast the fashionably arty French world (let alone the philistine, public school world of English culture) was simply more relaxed, less extreme. They had more shopping in them. The Art Deco world which Willett despises was the world of visual and applied art which most people, most shoppers, and most of the rich and the aspiring middle classes would have known about. (And I learned from Duncan’s book that Art Deco really was about shops, about Tiffany’s and Liberty’s and Lalique’s and the design and the shop windows of these top boutiques.)

On the evidence of Laqueur’s account of Weimar culture and Duncan’s account of the Art Deco world, I now see Willett’s world of Bauhaus and Constructivism – which I once considered the be-all and end-all of 1920s art – as only one strand, just one part of a much bigger artistic and decorative universe.

Same goes for Willett’s couple of pages about Surrealism. Boy, he despises those guys. Again it was a bit of a shock to snap out of Willett’s wonderworld of Bauhaus-Constructivism to remember that there was this whole separate and different art movement afoot. Reading Ruth Brandon’s book, Surreal Lives would lead you to believe that it, Surrealism, was the big anti-bourgeois artistic movement of the day. Yet, from Willett’s point of view, focused on the Germany-Russia axis, Surrealism comes over as pitifully superficial froggy play acting.

He says it was unclear throughout the 1920s whether Surrealism even existed outside a handful of books made with ‘automatic writing’. When Hans Arp or Max Ernst went over to the Surrealist camp their work had nothing to tell the German avant-garde. They were German, so it was more a case of the German avant-garde coming to the rescue of a pitifully under-resourced French movement.

There was in fact something slightly factitious about the very idea of Surrealist painting right up to the point when Dali arrived with his distinctively creepy academicism. (p.172)

Surrealism’s moving force, the dominating poet André Breton, is contrasted with Willett’s heroes.

Breton’s romantic irrationalism, his belief in mysterious forces and the quasi-mediumistic use of the imagination could scarcely have been more opposed to the open-eyed utilitarianism of the younger Germans, with their respect for objective facts. (p.172)

I was pleased to read that Willett, like me, finds the Surrealists ‘anti-bourgeois’ antics simply stupid schoolboy posturing.

As for his group’s aggressive public gestures, like Georges Sadoul’s insulting postcard to a Saint-Cyr colonel or the wanton breaking-up of a nightclub that dared to call itself after Les Chants de Maldoror, one of their cult books, these were bound to seem trivial to anyone who had experienced serious political violence. (p.172)

Although the Surrealists bandied around the term ‘revolution’ they didn’t know what it meant, they had no idea what it was like to live through the revolutionary turmoil of Soviet Russia or the troubled years 1918 to 1923 in post-war Germany which saw repeated attempts at communist coups in Munich and Berlin, accompanied by savage street fighting between left and right.

Although the Surrealists pretentiously incorporated the world ‘revolution’ into the title of their magazine, La Révolution surréaliste, none of them knew what a revolution really entailed, and

Breton, Aragon and Eluard remained none the less bourgeois in their life styles and their concern with bella figura. (p.172)

There were no massacres in the streets of comfortable Paris, and certainly nothing to disturb the salon of the Princess Edmond de Polignac, who subsidised the first performance of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex or to upset the Comtesse de Noailles, who commissioned Léger to decorate her villa at Hyères and later underwrote the ‘daring’ Surrealist film by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, L’Age d’Or (1930).

In this, as in so many other things, French intellectuals come across as stylish poseurs performing for impeccably aristocratic patrons.

3. Willett’s account is clotted and cluttered

The text is clotted with names, absolutely stuffed. To give two symptoms, each chapter begins with a paragraph-long summary of its content, which is itself often quite exhausting to read; and then the text itself suffers from being rammed full of as many names as Willett can squeeze in.

Almost every sentence has at least one if not more subordinate clauses which add in details about the subject’s other activities, or another organisation they were part of, or a list of other people they were connected to, or examples of other artists doing the same kind of thing.

Here’s a typical chapter summary, of ‘Chapter 16 Theatre for the machine age: Piscator, Brecht, the Bauhaus, agitprop‘:

Middlebrow entertainment and the revaluation of the classics. The challenge of cinema. Piscator’s first political productions and his development of documentary theatre; splitting of the Volksbühne and formation of his own company; his historic productions of 1927-8 with their use of machinery and film. The new dramaturgy and the problem of suitable plays. Brecht’s reflection of technology, notably in Mann ist Mann; his collaboration with Kurt Weill and the success of the Threepenny Opera; epic theatre and the collective approach. Boom of ‘the theatre of the times’ in 1928-9. Experiments at the Bauhaus: Schlemmer, Moholy, Nagy, Gropius’s ‘Totaltheater’ etc;. The Communist agitprop movement. Parallel developments in Russia: Meyerhold, TRAM, Tretiakoff.

Quite tiring to read, isn’t it? And that’s before you get to the actual text itself.

So Eisenstein could legitimately adopt circus techniques, just as Grosz and Mehring could appear in cabaret and Brecht before leaving Munich worked on the stage and film sketches of that great comic Karl Valentin. In 1925 a certain Walter von Hollander proposed what he called ‘education by revue’, the recruiting of writers like Mehring, Tucholsky and Weinert to ‘fill the marvellous revue form with the wit and vigour of our time’. This form was itself a kind of montage, and Reinhardt seems to have planned a ‘Revue for the Ruhr’ to which Brecht would contribute – ‘A workers’ revue’ was the critic Herbert Ihering’s description – while Piscator too hoped to open his first season with his own company in 1927 by a revue drawing on the mixed talents of his new ‘dramaturgical collective’. This scheme came to nothing, though Piscator’s earlier ‘red Revue’ – the Revue roter Rummel of 1924 – became important for the travelling agit-prop groups which various communist bodies now began forming on the model of the Soviet ‘Blue Blouses’. (p.110)

Breathless long sentences packed with names and works ranging across places and people and theatres and countries, all about everything. This is because Willett is at pains to convey his one big idea – the astonishing interconnectedness of the world of the 1920s European avant-garde – at every possible opportunity, and so embodies it in the chapter summaries, in his diagrams of interconnectedness, extending it even down to the level of individual sentences.

The tendency to prose overstuffed with facts is not helped by another key aspect of the subject matter which was the proliferation of acronyms and initialisms. For example the tendency of left-wing organisations to endlessly fragment and reorganise, especially in Russia where, as revolutionary excitement slowly morphed into totalitarian bureaucracy, there was no stopping the endless setting up of organisations and departments.

Becher, Anor Gabór and the Young Communist functionary Alfred Kurella, who that autumn [of 1927] were part of a delegation to the tenth anniversary celebrations [of the October Revolution] in Moscow, also attended the IBRL’s foundation meeting and undertook to form a German section of the body. Simultaneously some of the surviving adherents of the earlier Red Group decided to set up a sister organisation which would correspond to the Association of Artists of the Russian Revolution, an essentially academic body now posing as Proletarian. Both plans materialised in the following year, when the new German Revolutionary Artists Association (or ARBKD) was founded in March and the Proletarian-Revolutionary Writers’ League (BPRS) in October. (p.173)

Every paragraph is like that.

4. Very historical

Willett’s approach is very historical. As a student I found it thrilling the way he relates the evolving ideas of his galaxy of avant-garde writers, artists and architects – Grosz and Dix, Gropius and Le Corbusier, Moholy-Nagy and Meyerhold, Rodchenko and Eistenstein, Piscator and Brecht – to the fast-changing political situations in Weimar Germany and Soviet Russia, which, being equally ignorant of, I also found a revelation.

Now, more familiar with this sorry history, I found the book a little obviously chronological. Thus:

- Chapter six – Revolution and the arts: Germany 1918-20, from Arbeitsrat to Dada

- Chapter seven – Paris postwar: Dada, Les Six, the Swedish ballet, Le Corbusier

- Chapter eight – The crucial period 1921-3; international relations and development of the media; Lenin and the New Economic Policy; Stresemann and German stabilisation

It proceeds with very much the straightforward chronology of a school textbook.

5. Not very analytical

The helter-skelter of fraught political developments in both countries – the long lists of names, their interconnections emphasised at every opportunity – these give a tremendous sense of excitement to his account, a sense that scores of exciting artists were involved in all these fast-moving and radically experimental movements.

But, at the end of the day, I didn’t come away with any new ideas or sense of enlightenment. All the avant-garde artists he describes were responding to two basic impulses:

- The advent of the Machine Age (meaning gramophone, cars, airplanes, cruise ships, portable cameras, film) which prompted experiments in all the new media and the sense that all previous art was redundant.

- The Bolshevik Revolution – which inspired far-left opinions among the artists he deals with and inspired, most obviously, the agitprop experiments in Russia and Piscator and Brecht’s experiments in Germany – theatre in the round, with few if any props, the projection onto the walls of moving pictures or graphs or newspaper headlines – all designed to make the audience think (i.e. agree with the playwright and the director’s communist views).

But we sort of know about these already. From Peter Gay’s book, and then even more so Walter Laqueur’s book, I came away with a strong sense of the achievement and importance of particular individuals, and their distinctive ideas. Thomas Mann emerges as the representative novelist of the period and Laqueur’s book gives you a sense of the development of his political or social thought (the way he slowly came round to support the Republic) and of his works, especially the complex of currents found in his masterpiece, The Magic Mountain.

Willett just doesn’t give himself the space or time to do that. In the relentless blizzard of lists and connections only relatively superficial aspects of the countless works referenced are ever mentioned. Thus Piscator’s main theatrical innovation was to project moving pictures, graphs and statistics onto the backdrops of the stage, accompanying or counter-pointing the action. That’s it. We nowhere get a sense of the specific images or facts used in any one production, rather a quick list of the productions, of the involvement of Brecht or whoever in the writing, of Weill or Eisler in the music, before Willett is off comparing it with similar productions by Meyerhold in Moscow. Always he is hurrying off to make comparisons and links.

Thus there is:

6. Very little analysis of specific works

I think the book would have benefited from slowing down and studying half a dozen key works in a little more detail. Given the funky design of the book into pages with double columns of text, with each chapter introduced by a functionalist summary in bold black type, it wouldn’t have been going much further to insert page-long special features on, say, The Threepenny Opera (1928) or Le Corbusier’s Weissenhof Estate housing in Stuttgart (1927).

Just some concrete examples of what the style was about, how it worked, and what kind of legacy it left would have significantly lifted the book and left the reader with concrete, specific instances. As it is the blizzard of names, acronyms and historical events is overwhelming and, ultimately, numbing.

The Wall Street Crash leads to the end of the Weimar experiment

In the last chapters Willett, as per his basic chronological structure, deals with the end of the Weimar Republic.

America started it, by having the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. American banks were plunged into crisis and clawed back all their outstanding loans in order to stay solvent. Businesses all across America went bankrupt, but America had also been the main lender to the German government during the reconstruction years after the War.

It had been an American, Charles G. Dawes, who chaired the committee which came up with the Dawes Plan of 1924. This arranged for loans to be made to the German government, which it would invest to boost industry, which would increase the tax revenue, which it would then use to pay off the punishing reparations which France demanded at the end of the war. And these reparations France would use to pay off the large debts to America which France had incurred during the war.

It was the guarantee of American money which stabilised the German currency after the hyper-inflation crisis of 1923, and enabled the five years of economic and social stability which followed, 1924-29, the high point for Willett of the Republic’s artistic and cultural output. All funded, let it be remembered, by capitalist America’s money.

The Wall Street Crash ended that. American banks demanded their loans back. German industry collapsed. Unemployment shot up from a few hundred thousand to six million at the point where Hitler took power. Six million! People voted, logically enough, for the man who promised economic and national salvation.

In this respect, the failure of American capitalism, which the crash represented, directly led to the rise of Hitler, to the Second World War, to the invasion of Russia, the partition of Europe and the Cold War. No Wall Street Crash, none of that would have happened.

A closed worldview leads to failure

Anyway, given that all this is relatively well known (it was all taught to my kids for their history GCSEs) what Willett’s account brings out is the short-sighted stupidity of the Communist Party of Germany and their Soviet masters.

Right up till the end of the Weimar Republic, the Communists (the KPD) refused to co-operate with the more centrist socialists (the SPD) in forming a government, and often campaigned against them. Willett quotes a contemporary communist paper saying an SPD government and a disunited working class would be a vastly worse evil than a fascist government and a unified working class. Well, they got the fascist government they hoped for.

In fact, the communists wanted a Big Crisis to come because they were convinced that it would bring about the German Revolution (which would itself trigger revolution across Europe and the triumph of communism).

How could they have been so stupid?

Because they lived in a bubble of self-reaffirming views. I thought this passage was eerily relevant to discussions today about people’s use of the internet, about modern digital citizens tending to select the news media, journalism and art and movies and so on, which reinforce their views and convince them that everyone thinks like them.

To some extent the extreme unreality of this attitude, with its deceptive aura of do-or-die militancy, sprang from the old left-wing tendency to underrate the non-urban population, which is where the Nazis had so much of their strength. At the same time it reflects a certain social and cultural isolation which sprang from the KPD’s own successes. For the German Communists lived in a world of their own, where the party catered for every interest. Once committed to the movement you not only read AIZ and the party political press: your literary tastes were catered for by the Büchergilde Gutenberg and the Malik-Verlag and corrected by Die Linkskurve; your entertainment was provided by Piscator’s and other collectives, by the agitprop groups, the Soviet cinema, the Lehrstück and the music of Eisler and Weill; your ideology was formed by Radványi’s MASch or Marxist Workers’ School; your visual standards by Grosz and Kollwitz and the CIAM; your view of Russia by the IAH. If you were a photographer, you joined a Workers-Photographers’ group; if a sportsman, some kind of Workers’ Sports Association; whatever your special interests Münzenberg [the German communist publisher and propagandist] had a journal for you. You followed the same issues, you lobbied for the same causes. (p.204)

And you failed. Your cause failed and everyone you knew was arrested, murdered or fled abroad.

A worldview which is based on a self-confirming bubble of like-minded information is proto-totalitarian, inevitably seeks to ban or suppress any opposing points of view, and is doomed to fail in an ever-changing world where people with views unlike yours outnumber you.

A democratic culture is one where people acknowledge the utter difference of other people’s views, no matter how vile and distasteful, and commit to argument, debate and so on, but also to conceding the point where the opponents are, quite simply, in the majority. You can’t always win, no matter how God-given you think your views of the world. But you can’t even hope to win unless you concede that your opponents are people, too, with deeply held views. Just calling them ‘social-fascists’ (as the KPD called the SPD) or ‘racists’ or ‘sexists’ (as bienpensant liberals call anyone who opposes them today) won’t change anything. You don’t stand a chance of prevailing unless you listen to, learn from, and sympathise with, the beliefs of people you profoundly oppose.

A third of the German population voted for Hitler in 1932 and the majority switched to Führer worship once he came to power. The avant-garde artists Willett catalogues in such mind-numbing profusion pioneered techniques of design and architecture, theatre production and photography, which still seem astonishingly modern to us today. But theirs was an entirely urban movement created among a hard core of like-minded bohemians. They didn’t even reach out to university students (as Laqueur’s chapter on universities makes abundantly clear), let alone the majority of Germany’s population, which didn’t live in fashionable cities.

Over the three days it took to read this book, I’ve also read newspapers packed with stories about Donald Trump and listened to radio features about Trump’s first year in office, so it’s been difficult not to draw the obvious comparisons between Willett’s right-thinking urban artists who failed to stop Hitler and the American urban liberals who failed to stop Trump.

American liberals – middle class, mainly confined to the big cities, convinced of the rightness of their virtuous views on sexism and racism – snobbishly dismissing Trump as a flashy businessman with a weird haircut who never got a degree, throwing up their hands in horror at his racist, sexist remarks. And utterly failing to realise that these were all precisely the tokens which made him appeal to non-urban, non-university-educated, non-middle class, and economically suffering, small-town populations.

Also, as in Weimar, the left devoted so much energy to tearing itself apart – Hillary versus Sanders – that it only woke up to the threat from the right-wing contender too late.

Ditto Brexit in Britain. The liberal elite (Guardian, BBC) based in London just couldn’t believe it could happen, led as it was by obvious buffoons like Farage and Johnson, people who make ‘racist’, ‘sexist’ comments and so, therefore, obviously didn’t count and shouldn’t be taken seriously.

Because only people who talk like us, think like us, are politically correct like us, can possibly count or matter.

Well, they were proved wrong. In a democracy everyone’s vote counts as precisely ‘1’, no matter whether they’re a professor of gender studies at Cambridge (which had the highest Remain vote) or a drug dealer in Middlesborough (which had the highest Leave vote).

Dismissing Farage and Johnson as idiots, and anyone who voted Leave as a racist, was simply a way of avoiding looking into and trying to address the profound social and economic issues which drove the vote.

Well, the extremely clever sophisticates of Berlin also thought Hitler was a provincial bumpkin, a ludicrous loudmouth spouting absurd opinions about Jews which no sensible person could believe, who didn’t stand a chance of gaining power. And by focusing on the (ridiculous little) man they consistently failed to address the vast economic and social crisis which underpinned his support and brought him to power. Ditto Trump. Ditto Brexit.

Some optimists believe the reason for studying history is so we can learn from it. But my impression is that the key lesson of history is that – people never learn from history.

Related links

Related reviews