Judy Chicago is an American art celebrity, a feminist superstar, a ‘trailblazing artist, author, educator, cultural historian’, a godmother of modern American feminist art.

Born Judith Cohen in 1939, Chicago struggled against the patriarchal condescension of the art world in the mid-1960s and eventually made a number of drastic decisions. The most striking was, in 1970, changing her name to adopt the city of her birth, thus erasing the gender-controlling aspects of going by either her father or husband’s names. She assembled collectives of women artists and founded the first feminist art program in the United States at California State University, Fresno.

The Dinner Party

Her most famous work is ‘The Dinner Party’ which she began in 1974 and can be said to summarise many of her concerns and practices.

‘The Dinner Party’ is not a painting or sculpture but an installation made of multiple elements: most obviously it consists of a large triangular table on which are 39 elaborate place settings for 39 mythical and historical famous women such as Sojourner Truth, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Empress Theodora of Byzantium, Virginia Woolf and so on.

So it is 1) an unconventional object, not painting, sculpture or quite installation, 2) setting out to address one of Chicago’s central concerns, which is the erasure and omission of eminent women from history, secular history, religious history, art history, all of it created and written by men.

It’s also a characteristic piece in that it was 3) a collaboration which required a lot of assistance from collaborating artists and assistants. Over the 8 years of its creation some 400 women worked on it, mostly volunteers.

Participants gather in The Dinner Party studio, Santa Monica, CA, 1978. Courtesy the Judy Chicago Visual Archive, Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

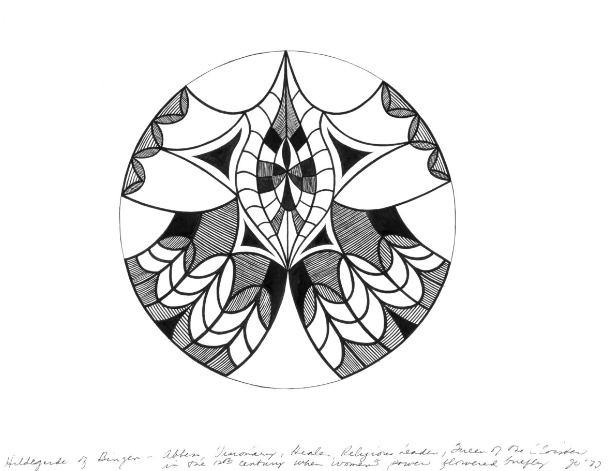

‘The Dinner Party’ is also characteristic in that 4) it confronts women’s sexuality head-on by having all of the 39 plates being vulvar in shape i.e. based on the shape and pattern of a woman’s genitals, a pattern she came to call ‘butterfly-vagina’ imagery. Broadly speaking, this is consists of a vertical oval representing the vaginal opening, with the folds of skin surrounding it (the labia minoria, labia majora and so on [according to the anatomy diagram I’m consulting]) represented in different ways, from folds of fabric to entirely schematic geometric patterns. Each of the 39 plates is a variation on the butterfly-vagina motif but vulvar imagery re-occurs frequently throughout Chicago’s oeuvre.

Hildegarde of Bingen plate line drawing from ‘The Dinner Party’ (1977) by Judy Chicago © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY Exhibition prints courtesy of the artist

‘The Dinner Party’ is also typical of Chicago’s work 5) in emphasising crafts, such as crockery and the needlework and fabrics which ornament the table, in foregrounding crafts which have traditionally, in the male-dominated art world, been relegated to a position inferior to painting and sculpture.

It is also characteristic in yet another way, in that 6) it went on tour, rather like a rock band, being shown in 16 venues in six countries on three continents to a viewing audience of 15 million. The very fact that the publicity around it emphasises these stats indicates the showbiz, world tour aspect of Chicago’s practice and reputation.

In this exhibition at Serpentine North ‘The Dinner Party’ has an alcove to itself, which, alas, doesn’t show the table itself (which has come to rest as a permanent installation at the Centre for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York) but displays various resources about it. So there are print versions of the designs on each plate, along with early colour studies of the banners used in the finished work and sketchbooks that reveal the working process and components that led up to it. There are three video screens showing interviews with members of the studio, documentary footage and a film that takes visitors on a tour of the work led by Chicago herself.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing the alcove containing sketches and videos relating to ‘the Dinner Party’ © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine

Maybe the last way in which ‘the Dinner Party’ is characteristic of Chicago’s work is that 7) it was made a long time ago, begun in 1974, half a century ago. Arguably, it speaks to a particular time and place and stage in the development of feminism as an ideology or collection of positions which have been eclipsed and superseded. Far from being occluded from history, nowadays you can’t go into a bookshop, turn on TV or radio, without encountering books, plays, films, documentaries and no end of other information about women in history, science, the arts and every other sphere of human activity. Which doesn’t detract from its power as a concept and a work and as a piece of feminist art history.

It’s interesting to read The Dinner Party Wikipedia article for the contemporary critical response among women critics and artists and then among Black women, to get a feel for how endlessly contentious these subjects are, and how the fiercest opposition often comes, not from the famous Patriarchy, but from members of your own movement.

Atmospheres

Talking of art from a long time ago, the second of Serpentine North’s ‘alcoves’ (or brick-lined passages) is devoted to an even older piece, or concept for multiple pieces, the use of coloured smoke.

Between 1968 and 1974, Chicago explored the male-dominated field of pyrotechnics and carried out a series of immersive, site-specific performances collectively known as ‘Atmospheres’. In these works Chicago moved right outside conventional artistic boundaries to use smoke as a medium to create expansive drawings in space. According to the curators:

Chicago saw ‘Atmospheres’ as a “gesture of liberation” that marked the release of colour previously contained within the “rigid structures” of her drawings and paintings and freed her from societal expectations.

She used smoke machines, fireworks, road flares and dry ice to ‘transform and soften the landscape’ and, crucially, to introduce ‘a feminine impulse into the environment.’ This would later become a central concern.

By their nature ephemeral, Chicago documented the smoke pieces through video and photography which is why a dozen or so photos and several videos projected onto hanging screens record the performances.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing the alcove/passage devoted to ‘Atmospheres’ © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine

Apparently, 40-plus years later, Chicago was invited to recreate or develop the idea of pyrotechnic art so that alongside the 70s footage there are films of much more recent events where, in what look like big festival-style events, she set off smoke displays and what look like pretty standard firework displays, at night, in American and European cities, to the whoops and cheers of delighted crowds.

Comparing these movies from 2019 and 2020 with the original small-scale, delicate and evocative films from the 1960s shows you how far American or Western culture has fallen, how so much that was novel or strange has been sucked into show business at VIP prices, with little or no space for strange, eccentric, individual gestures and thoughts.

The footage of naked young women painted red and green dancing in the desert holding smoke canisters in their hands are powerful not only because of their youth and beauty, but because their mysterious gestures, designed to invoke women-only rites and rituals, along with the very grainy quality of the old 16mm footage, hark back to a lost age of innocence and optimism.

Then (sweet, amateurish and interesting)

‘Smoke Bodies’ from ‘Women and Smoke’ by Judy Chicago (1972) Fireworks performance performed in the California Desert © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

Now (slick, professional and boring)

‘Purple Poem for Miami’ by Judy Chicago (2019) Fireworks performance commissioned by the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami in conjunction with the exhibition Judy ‘Chicago: A Reckoning, 2018 to 2019’© Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, New York Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

‘Turning rebellion into money’ as the Clash predicted, 50 years ago.

Revelations

But despite The Dinner Party’s central place in Chicago’s oeuvre and biography, this exhibition is not about it. The exhibition is titled ‘Revelations’ because this is the title of a book Chicago started working on in the early 70s and added to throughout the period of the creation of ‘The Dinner Party’, but which only now, 50 years later, is finally being published.

The idea is that this book expressed fundamental feminist and religious beliefs which have underpinned Chicago’s practice ever since (at one stage it was titled ‘Revelations of the Goddess’). We are told that only recently has she found the time to revise and complete the book as a kind of illustrated manuscript, a little in the style of William Blake’s self-illustrated books. To quote the blurb:

‘Revelations’ draws on Chicago’s extensive research into goddess worship and women’s history, offering readers a radical retelling of mythological creation and sharing Chicago’s lifelong vision of a just and equitable world.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing a display case containing pages from the illuminated edition of ‘Revelations’ © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

Not only did she complete it, but got it published. This exhibition is timed and designed to coincide with the official publication of ‘Revelations’ by quality art publisher Thames & Hudson. Which explains why the show a) displays selected pages from the final book b) is laid out according to the central concepts of feminist theology which Chicago develops in the book and c) of course, copies are stacked high for visitors to buy in the exhibition shop (or on Amazon).

Apparently, if you download the app using the QR code supplied on the wall labels, you can listen to Chicago reading excerpts from the book which vary as you walk around the gallery.

Feminist theology

‘Feminist theology’ I hear you ask? Yes, for although Chicago rejects the patriarchy and man-centric male control of the art world, of politics and the world in general, she nonetheless appears to believe in a God.

As far as I could tell this god is female. God is a woman. In this respect her thinking amounts to a mirror image of male theology: there is a God, but she is a woman and therefore created Woman first and Man simply to be her clumsy helpmate. Crucially – and a point she comes back to again and again – the most fundamental act of creation is female because it is giving birth. Only women give birth, in a shattering and dangerous and exhilarating process which has been both ignored, suppressed, never mentioned and never portrayed in patriarchal art. Addressing this glaring omission explains why there are series of works addressing God the (Female) Creator and why the entire exhibition opens with a big, a really, really big wide frieze depicting the creation myth according to Judy, complete with text explaining the all-female creation of the universe in cod Biblical phraseology.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing ‘In the Beginning’, her feminist creation myth (1982) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

This focus on the true, female nature of creation also explains why, later in the show, there’s a series of works depicting childbirth – not in realistically messy detail, not in blood-spattered photographs – but stylised into the mythological cartoon style Chicago developed and perfected in the later 1970s and 80s. This series is titled ‘The Birth Project’ and includes a number of finished works alongside preparatory drawings and sketches. Pretty much all of them show the act of birth from the business end, facing directly between a woman’s legs so as to see the parted thighs, the opening vulva and anus, with the breasts like two hills in the distance and, often, no head in sight.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing ‘The Crowning’ (1983) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

The correlation between the female body and landscape is no accident – in this vision, women make the world and so are the landscape.

Evolution from abstract to cartoon style

The exhibition actually starts back before ‘The Dinner Party’ or ‘Atmospheres’ with a set of her earliest works, which are far more conventional drawings on paper consisting of lightly drawn geometric shapes shaded with pastel colours.

These are very soothing and calming. They reminded me a bit of the Hilma af Klimt abstracts shown at Tate Modern last year, or of the visionary drawings of Emma Kunz shown here at the Serpentine 5 years ago but much lighter and less cluttered than either. Simpler, airier. Maybe more like Agnes Martin.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing early drawings from the late 1960s) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

Placed next to them are drawings from just a few years later which demonstrate a far more assertive use of colour, with the structure of the shapes more obviously defined, using bolder colours and with the grading of the colours from intense to pale, creating a more dynamic effect.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing early drawings from the early and mid-1970s © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

The curators make the point that the entire exhibition has a strong emphasis on Chicago’s drawings and sketches, maybe half the pieces here are drawings, and this is also the pretext for some quotes by Chicago on the centrality of drawing to her practice, before she gets near to the later, larger, more finished works.

Anyway I’m sharing these early pieces to highlight the next step in her development which is to treat human beings in much the same abstract shadow style, showing only the silhouette emphasised by dark shadowing, and using bold colours which shade away into pastel hues, which has the effect of making the images dynamic and, at the same time, simplified and cartoony.

‘Wrestling with the Shadow for Her Life’ from ‘Shadow Drawings’ (1982) by Judy Chicago © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY Courtesy of the artist

There are a dozen or so images like this and I liked them, probably because I like cartoons, I like strong defined outlines which is why, for example, I worship Degas. The flexible distorted postures of the human figures also appealed because they reminded me of both Matisse and Picasso who, in different ways, did something similar to the human body, turning it into bendy dancing outlines. Probably there’s a strong feminist message to this image, as to all the others, but after a while I stopped reading the wall captions and just enjoyed the pictures.

There’s a subset of these which appear to address how horrible men are, a series titled ‘PowerPlay’ (1982 to 1987) which, as the curators put it, ‘interrogate notions of power, social conditioning, and the construct of masculinity’ – or, as a normal person might put it, are entertaining, comic cartoons.

So, for example, we have an imagine of a muscly man grasping a steering wheel which has morphed out of a version of planet earth which is going up in flames – presumably showing how toxic masculinity has instrumentalised the earth and is driving it down the road to ruin.

There’s a comic image of one of her shadow silhouette man with his willy hanging between his legs, letting rip a flow of yellow pee onto the earth. Yes folks, toxic men pissing all over nature (presumably because women don’t pee or, if they do, it’s in a discreet, non-toxic and environmentally friendly kind of way).

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing shadow drawings of toxic men from the early 1980s © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

Simplistic images conveying a simplistic message: man bad. Destroy environment. Woman good. Save planet.

The environmental turn

Which goes to show that, like many older artists, half-way through her career Chicago’s work began to incorporate environmental and green concerns. Probably it was there from the start, as the green movement was born around the same time as feminism and was part of the studenty-60s counterculture rebellion climate which Chicago came out of. But whatever the history of her engagement with the issue, this exhibition goes on from the cartoon men to show work in which she consciously focuses on green issues.

One wall holds 13 or so smallish prints, from 2013 and 2014, of endangered animals outlined in white on a jet black background, and each one is given a text, written in Chicago’s characteristic cursive script, pleading with us to save the planet.

‘Stranded’ by Judy Chicago in ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

These, we are told, are all part of the #CreateArtForEarth campaign which Chicago set up along with the artist Swoon and Jane Fonda (of all people) who, apparently already runs an environmental campaign called Fire Drill Fridays.

Judge for yourself but these images all seemed to me to be, well, er, a little amateurish. At about this point in the exhibition the thought occurred that a lot of Chicago’s mid-period and later art depends quite heavily on the worthiness of the cause as much as, or more than, its aesthetic quality.

A tell-tale indicator of this is the increasing presence – you might say dominance – of text in the images. By the 2010s many, if not most, of the works here contain texts which ‘educate’ – or hector and harangue – the viewer, depending on taste.

Anyway, you too can contribute to #CreateArtForEarth just by posting on social media using the hashtag. You can upload anything, paintings, photos, sculptures, writings, poems, symbols, every little helps, and you can see how this matches the collaborative and co-operational mindset which I pointed out 35 years earlier in the heady ‘Dinner Party’ days.

I don’t want to come over as unduly cynical but as I read all this it did strike me as a prime example of ‘slacktivism’, whose dictionary definition is: ‘the practice of supporting a political or social cause by means such as social media or online petitions, characterized as involving very little effort or commitment.’ Uptick ‘Save the planet’. Like ‘End consumption’. There. That’s my contribution.

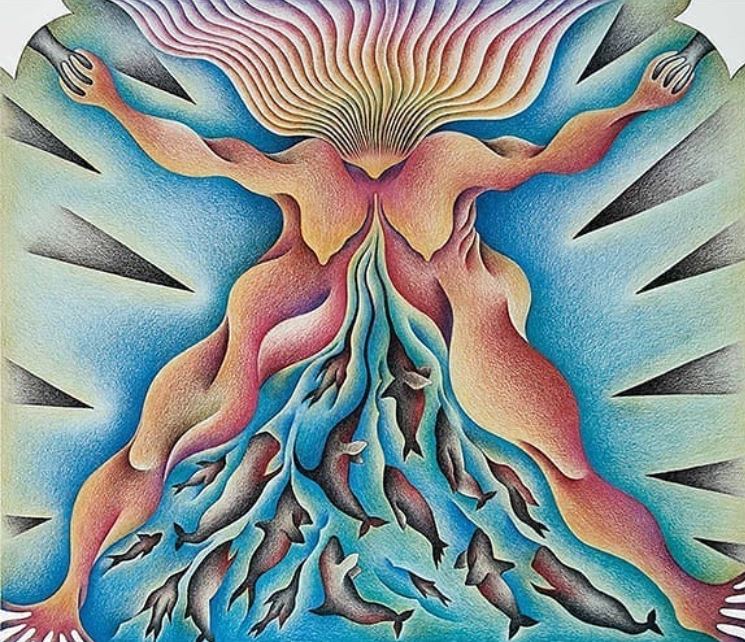

Anyway, the shadow cartoon style I highlighted earlier is combined with the environmentalism in one of the most successful pieces here, ‘Rainbow Warrior’ from 1980, named after Greenpeace’s activist ship. Another of her stylised naked women, apparently giving birth to the creatures of the sea. (The ‘rainbow warrior’ is, apparently, an ocean goddess from Inuit mythology, so it’s not just a whimsical image but an ethnographically accurate one.)

‘Rainbow Warrior – for Greenpeace’ by Judy Chicago (1980) in ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North. Collection of Paul and Rhonda Gerson © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, New York

Digression: 1930s posters

As I processed all these images of the human form simplified down to stylised silhouettes with the heavy use of shading and often multiple outlines as if echoing or mirroring the central one, plus the use of slogans or good causes – I knew I’d seen something similar before. It took me a while to realise they were reminding me of a certain type of poster from the 1930s, generally depicting armed struggle, the classical examples being from the Spanish Civil War, but sometimes Nazi Germany or Stalin’s USSR.

It tickled me that these images of muscle-bound, toxic male warriors are pretty much the last thing in the world Chicago would want to be associated with, but hopefully you can see the stylistic similarities. Not suggesting any kind of indebtedness, just the visual similarity.

Snapshot from Google Images showing cartoon figures relying on strong outlines, shadow, ‘echoes’ of silhouettes and simple colour palettes

What if women ruled the world?

The exhibition builds up to a finale in the very big, interactive and collaborative piece, ‘What if women ruled the world?’

The main product of this is a massive quilted banner covered in images and text, lots of text. It was a highly collaborative piece. Chicago formulated 10 or so ancillary questions to the main central one, such as [if women ruled the world] ‘Would men and women be equal?’, ‘Would buildings resemble wombs?’ and so on.

Rather mind-bogglingly the first person to answer all 11 questions ‘during a call to action at the ICA Miami in December 2022’ was Nadya Tolokonnikova, founding member of the all-women Russian punk band, Pussy Riot. Her prompt and enthusiastic response resulted in her being recruited by Chicago, an inveterate collaborator, in this new project.

In the end thousands of people replied, from all round the world, and these responses were ‘digitally threaded’ together to create the finished tapestry. Here’s my photo of it in the Serpentine which shows how it is made out of panels. At the centre sits an embroidered portrait-shaped rectangle containing the master question. If you look closely you can see how scattered around the rest of the quilt are long narrow ‘letterbox’ panels, which contain the 10 ancillary questions. And all the rest of the quilt is made up of smaller, letter-shaped panels containing answers contributed by respondents around the world, most of whom are represented by photos of themselves.

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing ‘What if women ruled the world?’ © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

You can see it in more detail, read more and watch the video, on the dedicated What if women ruled the world? website. (If you hover your cursor over the main image of the quilt it magnifies the individual panels so you can read the contributions and comments woven into it).

The exhibition here at the Serpentine includes, next to the main quilt, a set of decorated prints of each of the questions written out in Chicago’s attractive, cursive script.

A last-minute change

And with that you have completed your tour of the exhibition – laid out in Serpentine’s usual four long narrow galleries and 2 walk-through alcoves – and have arrived back at the massive frieze depicting her mythological depiction of the Female Goddess giving birth to the universe, which greeted us as we walked in the door.

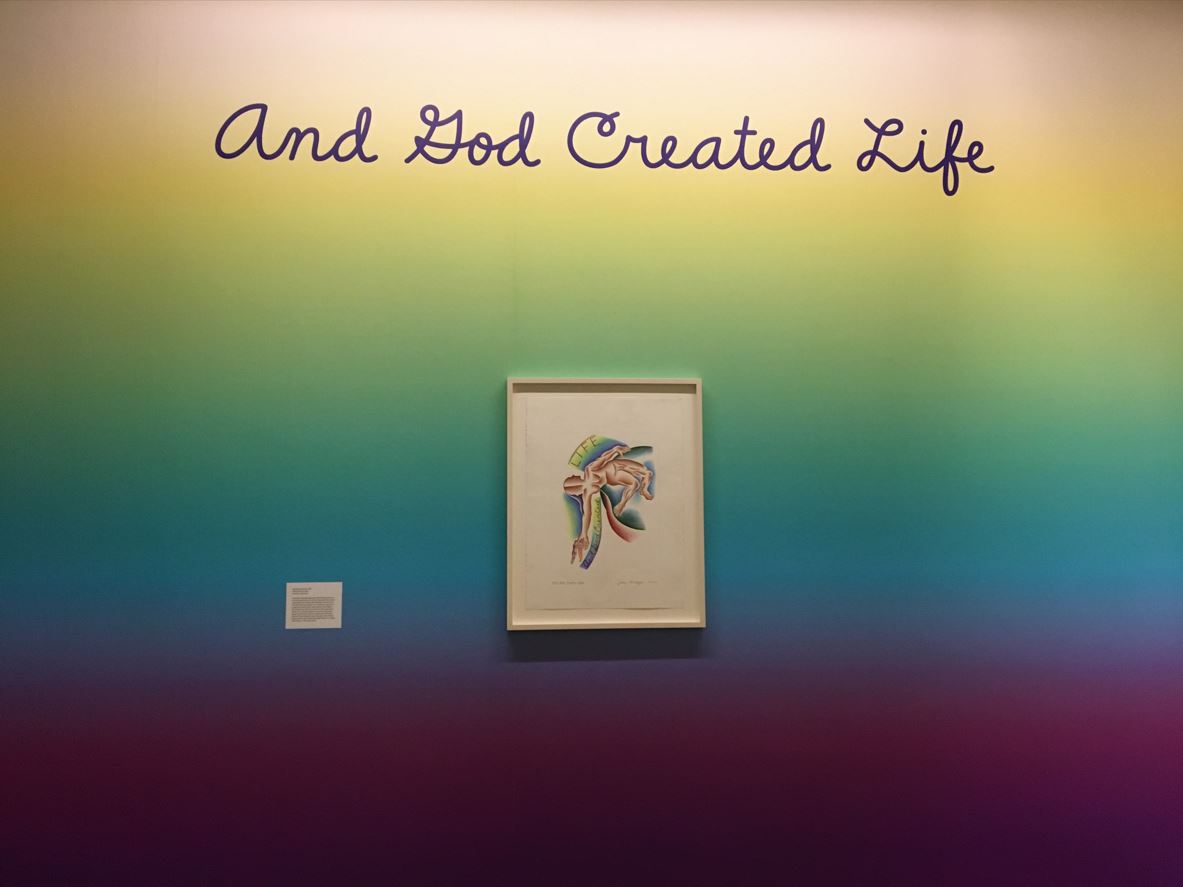

But there is one last wrinkle. On the wall next to the quilt, Chicago has created a piece specially for this show. It uses what had, by the 1980s become her characteristic rainbow palette, using her trademark Prismacolor pens, across which is written a text in her (just as characteristic) cursive hand saying: ‘And God Created Life.’

Beneath this is a normal-sized print depicting God as a hermaphrodite, displaying the primary and secondary characteristics of both a woman and a man (i.e. a vulva and a penis).

Installation view of ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ at Serpentine North showing ‘And God Created Life?’ (2023) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (photo by the author)

What??? Right next door is the huge frieze saying that God is a woman and created the universe using female techniques, body parts and substances (breast milk becoming rivers etc) and asserting that the fundamental act of creation, suppressed by millennia of patriarchy, is the unique ability of women to give birth. God. Woman. Universe.

But now, according to the curators:

Foregrounding a shift in the artist’s perspective from an inherently female position to an all-encompassing view, the exhibition culminates in ‘And God Created Life’ (2023). This is Chicago’s most recent work included in the exhibition and calls for an expanded and inclusive concept of God, one that is neither distinctly male or female.

Here, right on the very last wall, as it were on the last page of the book, in the last frame of the movie, with no further explanation, Chicago appears to revise and contradict pretty much everything the entire previous 50 years of her art was premised on. After spending 40 years telling us God is a woman now she’s telling us that…maybe our religious thinking should transcend the simplistic binary of male or female, for something less divisive and more inclusive…

It’s a weird curveball to throw right at the very end of the entire show and begs loads of questions which remain completely unanswered.

If you like vexatious questions about feminist mythology, God and the universe you can go away and worry about this puzzling turn of events at length. Or if, like me, you like pretty pictures and enjoy seeing how an artist’s style and ideas change and develop over time, then this a stimulating, often very beautiful, sometimes funny, sometimes a bit meh, but always interesting exhibition – with a mysterious sting in the tail!

‘And God Created Life’ by Judy Chicago (2023) © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York. Photo: © Donald Woodman/ARS, New York. Courtesy of the artist

And like all the shows at the two Serpentine galleries – it’s FREE! Go and enjoy, be inspired and, maybe, a little puzzled.

Related links

- Revelations by Judy Chicago continues at Serpentine North until 1 September 2024

- Judy Chicago website

- Through the Flower website

- What if women ruled the world? website

- Judy Chicago Wikipedia article

Other London exhibitions which featured Chicago

- Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art @ the Barbican (February 2024)

- RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology @ the Barbican (October 2023)

- Feminine power: the divine to the demonic @ the British Museum (May 2022)

- Pushing paper contemporary drawing from 1970 to now @ the British Museum (September 2019)

- The World Goes Pop @ Tate Modern (November 2015)

More Serpentine reviews

Feminist reviews

- Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970 to 1990 @ Tate Britain (2023)

- Complete list of my women artist reviews (104 reviews and counting)

- Women, Art and Society by Whitney Chadwick (2012)