God, he was a handsome man!

This is a really thorough, scholarly and in-depth biography-plus-analysis of the life and works of the godfather of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, part of the Thames and Hudson ‘World of Art’ series.

We are told that it was ‘written with the enthusiastic support of Duchamp’s widow’, and sets out to ‘challenge received ideas, misunderstanding and misinformation.’ No doubt, But to the casual gallery-goer like myself Duchamp is a ‘problem’ because his oeuvre seems so scattered and random: its three main elements are the Futurist paintings (chief among them Nude descending a stair); the readymades (like the bicycle wheel (1913), wine rack (1914), snow shovel (1915), or urinal (1917)); and then the obscure late works, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors and the even more obscure, Etants donnés.

This is the first and only account I’ve ever read which shows how these apparently very diverse products all arose naturally and consecutively from Duchamp’s artistic and philosophical interests. It creates a consistent narrative which explains and makes sense of them.

1. A crowded context

A common error in thinking about history – in thinking about the past generally – is to pick out one or two highlights from history – or ‘major’ writers or artists – and focusing on them alone, Picasso, the Holocaust, whatever.

But of course the past was as densely populated and packed with myriads of competing people, ideas, headlines, events, political parties, issues, theories and ideas, was as contingent and accidental – as the present. These ‘events’, these ‘great artists’, were intricately involved in the life of their times. Duchamp’s career more than most benefits from the thorough explanation of his historical context which the authors provide, because his artistic output is so ‘bitty’ and fragmented.

Thus the book begins by locating Duchamp’s life within a large family itself made up of artists (his grandfather was a well-known artist in Rouen, two of his brothers and one sister became artists). I particularly enjoyed the account of the art world of Paris circa 1905, when young Marcel moved there to join his brothers. It was fascinating to learn about the various ‘movements’ or clubs of artists famous in their own day, who have now completely disappeared from the historical record. In particular, it was news to learn that young Marcel initially made his way as a caricaturist, a cartoonist and illustrator for magazines.

Regarding caricature and humour, the book goes to some length to describe the intellectual life of the age, dwelling at length on theories of humour developed by writers like the poet Charles Baudelaire (On the essence of laughter, 1855) and Henri Bergson (Le Rire, 1900). Baudelaire thought comedy stemmed from the abrupt undermining of humanity’s aspirations towards goodness and angelic grace by moments of earthy reality or brute clumsiness. Pratfalls. Laurel and Hardy. On a verbal level, this structure is enacted in the double entendre or double meaning, which nowadays has come to mean saying something ‘respectable’ which also has a sexual interpretation or undertone.

Bergson thought humour was the result of perceiving people as machines or types, rather than individuals. In his view, lots of humour comes from an expectation of someone behaving with mechanical routine which is somehow undermined, or continuing to behave with routine nonchalance after some disaster. The example given is of a boring office functionary who every day dips his quill in the inkpot until one day his naughty colleagues fill it with mud. Ha ha.

Freud wrote an entire book giving a psychoanalytic theory of humour (Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, 1905) speculating that they are socially acceptable ways of sharing socially unacceptable base drives, like sadism (cruel humour) or sex (dirty jokes).

The juxtaposition of the cerebral and the coarse; the role of mechanism in humour; the fundamental primacy of the erotic. These are contemporary ideas which the intellectual Duchamp would have been familiar with and fed into his work and worldview.

1. The authors are just warming up with these early theories of humour; later the book will bring together a mind-boggling array of references to explicate Duchamp’s mature works.

2. This sequence is an example of what you could call the teleological approach of so many biographies of great personages – the tendency to find the seeds of later works in the personage’s earliest experiences and sayings, a direct line from infant, childhood or earliest experiences/productions to the adult’s life and work.

One example among many: the authors relate the fact that one of his earliest surviving sketches is of a lamp (Hanging glass lamp, 1904) to the fact that a gas lamp appears in both of his monumental late works, The Bride Stripped Bare and Étant donnés. Maybe, who can say. But it makes for an entertaining game of ‘sources and origins’.

2. Cubo-futurism

My favourite works of Duchamp’s, more than the readymades or the two big weird works, are his early semi-abstract paintings of walking human figures. I have always loved the energy of Italian Futurism and Wyndham Lewis’s Vorticism, so I love Duchamp’s masterly paintings of walking people turning into machines.

Or are they revealing the machine within the human; or showing the multiplicity of realities which the human mind converts into sequence but which, in an Einsteinian universe, may be permanently present; or his copying of the secrets of movement which in his day had only just been captured by pioneering photography. Or all four.

- Sad Young Man on a Train (1911)

- Nude descending a staircase number 1 (1911)

- Nude descending a staircase number 2 (1912)

- The King and Queen surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912) presumably the king and queen are on either side and a kind of river of flesh is pouring from bottom right to top left between them

- Bride (1912)

- Passage from Virgin to Bride (1912)

It’s fascinating to watch the progression in these paintings from the depiction of a kind of mechanised human through to full machine. It’s hard to see the last two of these paintings as human in any way.

And it’s here that the book makes the big link for me, because it shows in great detail how Duchamp, by 1913 completely disillusioned with painting, nonetheless used sketches and designs for the bride paintings as the basis of the strange, enigmatic and over-determined big work, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even which he would devote the next 15 years to creating, and tinker with for the rest of his life.

3. The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even

This is divided into two parts (top and bottom) with the top depicting the ‘bride’ in an extremely abstract, semi-mechanical form, and the bottom half originally showed the ‘bachelors’ competing for her favours. Apparently, at a very early stage, this was partly inspired by a fairground attraction where you could throw balls at puppets of a bride and groom, if you hit the bride she fell out of the bed stark naked (well, as naked as a puppet can be). Duchamp was attracted to the mechanical aspect, the puppet/mannequin aspect, the game aspect, and the sudden shock of nudity aspect. All four are recurrent themes.

By the time he painted the design onto this big glass sheet, the bride has evolved into a peculiar set of shapes in the top section, while the bachelors have evolved into a rack of male suits, now known – in the extensive mythology which Duchamp spun around the piece – as the ‘Malic Moulds’.

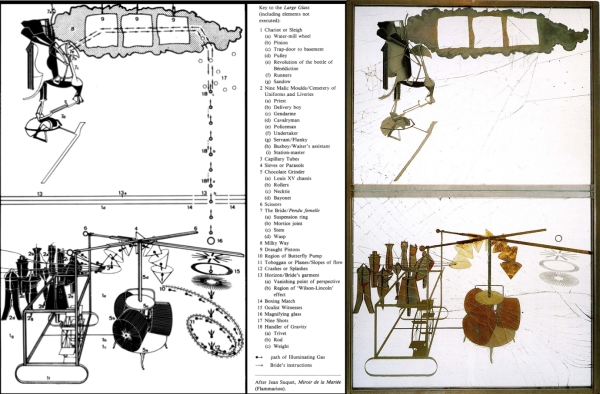

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915 to 1923) by Marcel Duchamp, as reconstructed by Richard Hamilton

But that makes it sound too rational and understandable. The authors devote tens of pages to analysing the slow evolution of his sketches and thinking. For example, the way the whole thing is painted onto a big sheet of glass undermines the idea of the canvas as an opaque object. Now it can be seen from both sides and changes aspect (and mood and meaning) depending on what it is placed in front of.

It’s really the steady abstraction and stylising of the images which takes some explaining. It’s part of Duchamp’s reaction against what he called retinal painting i.e. he lamented the way all painting from the impressionists onwards was made to be judged purely on its appearance, devoid of intellectual or symbolical meaning.

Duchamp found this retinal superficiality distressing and thought he could escape from the entire artistic trend of his day by moving towards a more scientific type of technical drawing (technical drawing having made up, as the authors point out in their thorough opening chapter, part of the school education of Duchamp’s generation).

Thus he made extensive preparatory sketches for all the different parts of the mechanism. Not only that, but he wrote an extensive set of notes, known as the The Green Box. Like T.S. Eliot’s contemporary Modernist poem, The Waste Land, The Bride Stripped Bare is designed to be read with its notes, the notes are an integral part of the understanding. In Duchamp’s case, the Green Box notes are more like a manual for understanding, a user’s guide. Thus the book includes a detailed analysis of every aspect of the mechanism, numbering and identifying all the parts, and explaining their derivations.

The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) by Marcel Duchamp (1915 to 1923) with annotated diagram of the parts

The authors go into rather mind-boggling detail in their analysis of the work. We learn the relevance of Einsteinian physics (is The Bride depicting a fourth dimension?), of medieval alchemy (note the design of the pipes and limbics of the mechanism), of Surreal theories of the erotic (for a start the way bride and bachelors are trapped in different quadrants of the work), and many other ideas and illusions. There is he importance of engineering design, technical drawing, the influence of Hertz’s discoveries about radio frequency, and so on and so on.

For once this isn’t a case of critics over-analysing a work of art because Duchamp himself, in his notes and in numerous interviews throughout his life, invoked a wealth of ideas, sources, and ideas which all contributed to manufacturing The Bride. Here’s a sample paragraph from the hundred or so about The Bride which make such bewildering and strangely gripping reading.

Attempts have been made to construct a narrative of the implied mechanical functioning of the Glass: to make visible the ‘cinematic blossoming’, as Duchamp put it, of the Bride and her interaction with the Bachelors. However, to succeed, these attempts would require the application of a consistent logic to operations that remain notional, inconsistent or at least multiply determined. The erotic is not rational. It is, perhaps, only a sexual encounter in the terms in which Breton saw it, as an extra-terrestrial observation of the inconsistencies, non-reciprocities and ambiguities of human sexuality. (p.107)

But:

The fascination with kinetic energy and ‘fields of force’ in both visual and linguistic terms runs throughout the Large Glass and the notes, which together form a fantastic catalogue of forms of propulsion and motion, and of the more invisible source of energy and modes of communication. For instance, the Bachelor Machine is powered by steam and is also an internal combustion engine; it includes gas and a waterfall, springs and buffers and a hook made of a substance of ‘oscillating density’. This was, Duchamp noted, a ‘sandow’, initially the name of a gymnastic apparatus made of extendable rubber, and by analogy a plane or glider launcher. The Bride runs on ‘love gasoline’; she is a car moving in slow gear; her stripping produces sparks; she is a 1-stroke engine, ‘desire-magneto’; the 2nd stroke controls the clockwork machinery (like ‘the throbbing jerk of the minute hand on electric clocks.’)

I began to find the authors’ extended investigation of the Bride, their exposition of Duchamp’s vast catalogue of ideas and interpretations, horribly addictive. Is the bride an avatar of Diana, Roman goddess of virginity? Or the Hindu goddess of destruction, Kali? Or is she the Virgin Mary, undergoing a secular apotheosis?

The discourse generated by this one intensely intellectualised piece will go on growing forever. It is a dizzying, terrifying and strangely reassuring thought…

4. Dada and the readymades

Once clear of the hermeneutic jungles of the Bride Stripped Bare, the book goes on to investigate Duchamp’s association with the anti-art movement, Dada, founded in Zurich in 1916 and which opened offices in Paris and even distant New York – and in his arm’s length relationship with Surrealism.

The key events of this period (1913 to 1923) is the invention of the readymade. At various points he selected a wine rack, a public urinal, a bicycle wheel on a stool, and a number of other everyday objects to exhibit in various art exhibitions in New York and Paris. The urinal is one of the most iconic works of the art of the century because thousands of conceptual artists have looked back to it for liberation, although the story of its exhibition is rather complicated (the way Duchamp signed the urinal R. Mutt, titled it Fountain, and anonymously submitted it to a art exhibition whose board of judges he himself was sitting on. When it was rejected by the others he resigned for the board and wrote a letter complaining about the outrageous treatment of Mr Mutt. And so on.)

The point was rather simple. What is art? When Duchamp posed this question, art theory was dominated by notions that the work of art had some kind of moral or spiritual or social purpose. The Victorians thought Art should portray The Beautiful. Mathew Arnold thought Art could protect and elevate the Imagination, protecting it from the brutal vulgarities of industrial society. Duchamp’s contemporaries in Soviet Russia thought Art could help bring about a new revolutionary society. The Surrealists’ leader, André Breton, thought Surrealism was a literary and artistic movement which would give people direct access to the unconscious mind and so liberate society from its repressions.

Everyone believed Art should do something.

Duchamp stands to the side of all this angsting and stressing. His readymades say that Art just is. One of the big things I’ve learned from this book, and from the Dali/Duchamp exhibition I recently visited, is the way Duchamp thought the key ingredient in a readymade was that it must not be beautiful. He was trying to get away from any idea whatsoever of ‘the aesthetic’.

While the nihilists of Dada tried to create a kind of anti-art, Duchamp spoke about creating an a-art, in the same sense as amorality doesn’t mean moral or immoral – it means having no morality at all. So a-art (or an-art, it doesn’t really work in English), means Art which has completely ceased to be Art. He wanted to evade the whole question of ‘aesthetics’ and ‘taste’, of ‘style’ of the special agency of the artist’s ‘touch’ – all of it. Hence:

- a snow shovel (1915)

- a ball of string between metal plates (1916)

- a comb (1916)

- Underwood typewriter cover (1916)

- a urinal (1917)

- a coat rack nailed to the floor (1917)

- a hat rack (1917)

- 50cc of Paris air in an ampoule (1919)

As regular readers of my blog know, I think all of these attitudes have been completely swallowed, subsumed and assimilated into our modern consumer capitalism. All art – whatever its original religious, spiritual or revolutionary intentions – is now just a range or series of decorative, ornamental and amusing brands in the Great Supermarket of life. Thus Duchamp’s great ‘revolutionary’ and ‘subversive’ icon is now available in any number of formats and channels, about as subversive as a Beatles T-shirt.

And as to ‘What is Art?’ Art is whatever art gallerists, art curators and art critics agree to call art. Simples.

5. Tinkering

By the mid-1920s Duchamp wasn’t painting and had finished The Bride. He was happy for word to go around that he had abandoned art for professional chess. Other Dada artists gave up altogether; it was the logical conclusion of their anti-Art stance.

But Duchamp in fact continued a career of low-level tinkering, especially in Surrealism (which he was never officially a member of. He:

- served on the editorial boards of the Surreal magazine, Minotaure and the New York magazine VVV

- designed the glass doors for Breton’s gallery Gradiva

- arranged a New York exhibition for Breton

- arranged the New York publication of Arcane 17 and Surrealism and painting

- designed the cover of Breton’s volume of poetry, Young cherry trees secured against hares

- served as ‘producer-arbitrator’ for the Exposition internationale de Surrealisme in 1938

- decorated the ‘First Papers of Surrealism’ exhibition in 1942 with reams of string and suggested the contributors’ faces in the catalogue were replaced by random photographs from the papers

- was co-presenter, with Breton, of Le Surrealisme en 1947 in Paris

- hand-coloured 999 fake plastic breasts to be included in the catalogue

- helped organise the 1959 Exposition internatoinale du Surréalisme with the theme of eroticism. Entry to one room was through a padded slit shaped like a vagina (Rrose Sélavy – Eros c’est la vie – was, after all, the punning meaning of the female drag identity Duchamp jokily created in the 1920s. Maybe Eros c’est mon oeuvre would have been more accurate.)

Retired from making, maybe, but quite obviously still involved with the art world.

6. Étant donnés

In fact, in secret, in the last twenty years of his life Duchamp was working on an even weirder piece, titled Étant donnés (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas, French: Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage).

The viewer has to look through two pinhole cracks in an old door to see a tableau of a nude woman lying on her back with her face hidden, her legs spread wide apart to reveal her hairless vulva, while one outstretched arm holds a gas lamp up against a landscape backdrop.

Duchamp prepared a ‘Manual of Instructions’ in a 4-ring binder explaining and illustrating how to assemble and disassemble the piece. It wasn’t displayed to the public until after Duchamp’s death in 1968 when it was installed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, also home to the Bride.

What on earth is it about, and how does it relate (if at all) to Duchamp’s earlier pieces?

Well, for a start, both rotate around naked women (hardly a very ‘revolutionary’ or ‘subversive’ subject – arguably the exact opposite). This takes us right back to the opening chapters where the authors had pointed out how many of Duchamp’s early cartoons and illustrations took the mickey out of the French feminist movement of 1905, and of women’s rights and aspirations, in general.

- Femme Cocher (1907) Marcel Duchamp Women had recently been allowed to drive hansom cabs. This cartoon, showing the absence of a woman driver parked outside a hotel which could be rented by the hour, suggests the woman driver is picking up extra money by popping in to ‘service’ her customer. Misogyny?

Moreover, before he adopted the Cubo-Futurist style, many of Duchamp’s earliest paintings depicted women stripped bare (aha) as they will appear in The bride and Étant donnés – walking, stretching, sitting – all naked. What is happening in an early painting such as The Bush (1911)?

In the same year, Portrait (Dulcinea) is an early attempt at portraying movement, the same woman appearing five times, each time progressively more undressed (though admittedly, this is not easy to make out).

So, naked women were a recurrent theme of his career. Indeed, one of the more easily readable exhibits at the current Dali/Duchamp exhibition is a photo of Duchamp playing chess with a naked lady in the 1960s. Old man and naked young woman. Hmm.

But this is just the obvious place to start, with the shockingly crude image of a naked woman. As with The Bride the authors t go on to use Duchamp’s own writings to bring out the dizzying multiplicity of meanings and interpretations which this strange, unsettling piece is capable of, for example reviewing the fifteen ‘operations’ in the instruction manual he wrote, which explain how the object was to be assembled.

As I read the densely written chapter about it, I realise that the detailed, hyper-precise instructions surrounding Étant Donnés, which all lead to a frustrating, flat, unemotional and profoundly disturbing outcome – all this reminds me of the detailed instructions which Samuel Beckett included in the texts of his carefully constructed artifice-plays. Same fanatical attention to detail for a similarly bleak and deliberately emotionally detached product.

Having finished the book and looking back in review of his career, the readymades seem almost the most accessible part of it. These two big works are genuinely subversive in the sense that, while invoking a kaleidoscope of interpretations, they continue to puzzle and baffle rational thought.

7. Duchamp cartoons

Which thought – possibly – brings us back to the very beginning of Duchamp’s career. His first exhibited works were shown at the 1907 Salon des Artistes Humoristes and his earliest paid work was as colleague to a gang of caricaturists and cartoonists who worked for Parisian magazines with titles like Cocorico, Le Rire (the Laugh) and Le Courrier français.

More than his interest in sex, or machines, or even chess, it is arguable that this taste for the drily humorous is the central spindle of his oeuvre.

Is the idea of the urinal not funny? Is he not, as thousands have pointed out before me, taking the piss out of the art world? Are not all his Surrealist interventions, ultimately, comical? And isn’t his last, great, puzzling work, in effect — a peep show of a naked lady? And the fact that so many critics have written about it with such po-faced seriousness, isn’t that itself comical?

You can’t help feeling all the way through, that Duchamp was having le dernier rire. After all, why shouldn’t modern art be itself funny, or the subject of humour?

- Nude descending a staircase

- Dude descending a stairmaster

- The rude descending a staircase

- Calvin and Hobbs descending a staircase

- C3PO descending a staircase

- Photo of Duchamp descending a staircase

- The truth about modern art

Toilet humour

- Duchamp was here

- A Duchamp urinal dress

- Marcel Duchamp taking the pissoir

- chez Duchamp

- dog readymades

- feminist

- Donald is thirsty

1950s revival

Lastly, in a very useful coda, the authors explain how Duchamp really had gone largely into retirement, living in a small New York apartment with the last of his many companions, when the 1950s dawned and with it the birth of an American avant-garde scene.

The Black Mountain College poets and writers and composers – John Cage the composer, Robert Rauschenberg the painter and Merce Cunningham the choreographer – took inspiration from Duchamp to oppose the intensely male and retinal work of the then dominant Abstract Expressionists, to kick back in the name of a dance and art and music which questioned its own premises, questioned its own ‘coherence’ and – in Cage’s music in particular – sought to escape the control and input of the composer completely, just as Duchamp had sought to escape the controlling influence of the artist in his readymades.

Rauschenberg’s close friend Jasper Johns used deliberately ‘found’ motifs like the American flag, numbers, letters, maps to depersonalise and demystify his art, and also combined it with readymade artefacts, just as Duchamp had. (As can be seen at the current Royal Academy exhibition about Johns.)

By 1960 his example was being quoted by all sorts of opponents of Abstract Expressionism, and his influence then spread across the outburst of new movements of the 60s – Fluxus, Arte Povera, Minimalism, Conceptualism, Land Art, Performance Art and so on. And is still very much with us today.

If the first half of the twentieth century belonged to the twin geniuses Matisse and Picasso, the second half belonged to this idiosyncratic, retiring but immensely intellectual and thought-provoking genius.

Conclusion

Duchamp’s greatest hits are summarised in the book’s promotional blurb:

- The originally controversial Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was a vital inspiration to the Futurists and remains a cubist classic.

- Fountain (a ready-made urinal) continues to inspire conceptual artists of all stripes.

- Large Glass (1915 to 1923) continues to beguile.

- Duchamp’s last work Étant Donnés (1946 to 1966) continues to disturb.

His achievement was to produce works and critical writings, ‘provocations and interventions’, which made innumerable artists, critics and curators reconsider their whole idea of what a work of art could be and mean. He opened up whole new vistas of the possible, and this is without listing some of the other ‘interventions’ the authors cover, like his half-serious financial ventures, his attempts to design and sell a rotorelief machine or – most teasingly of all – his teasing theory of the ‘infra-thin’.

It’s hard to imagine a one-volume book about Duchamp which could both cover the nuts and bolts of his biography and career, and also follow him out into the more vertiginous aspects of his relentless theorising about art in general and his own peculiar masterpieces in particular, better than this one.

Tu m’ (1918) Duchamp’s last work, painted as a commission to go above shelving in a New York apartment. In French the phrase requires a verb to complete it, so it’s unfinished. Pronounced in English it sounds like ‘tomb’ i.e. the summary and end of his painting career.