‘To systematise confusion and thereby contribute to a total discrediting of the world of reality.’

(Dalí’s aim, stated in his book, The Putrefied Donkey, 1930)

This exhibition of around 80 works by ‘father of conceptual art’ Marcel Duchamp, and ‘larger-than-life Surrealist’ Salvador Dalí aims to ‘throw light on their surprising relationship and its influence on the work of both artists.’ It also brings together in one place a number of their classic works; you can either read the story of their friendship in minute detail, or step back and marvel at a handful of works which changed the face of 20th century art (or both).

Lobster Telephone (1938) by Salvador Dali and Edward James. Photo by West Dean College, part of Edward James Foundation/© Salvador Dali, Fundacia Gala-Salvador Dali, DACS 2017

What have they got in common? Well, their surnames both start with D. But they come from different generations (Duchamp born 1887, Dalí born 1904), Duchamp was cerebral, ironic, thoughtful, retiring; Dalí was garish, gregarious, turning himself into a preposterous showman. On the face of it, Tweedleduchamp and Tweedledalí.

But after a meeting some time in 1930 they evidently got on. In 1933 Duchamp visited Dalí in Spain, they worked closely together on the ‘sceneography’ of the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition, wrote essays and comments on each other’s work and after the war, every summer Duchamp rented rooms in near Dalí’s house at Cadaqués in north-east Spain.

The show displays a number of photos of Duchamp on the beach, along with Dalí and his devoted wife, Gala, as well as chatty postcards the artists exchanged.

Early works

One of the interests of the show is the handful of really early works by both artists, showing what conventional beginnings they had. They both did conventional-looking portraits of their fathers, Duchamp’s adopting the flavour of the post-impressionists, Dalí’s showing the impact of post-war neo-classicising Modernism.

And there’s an interesting cubist work by Dalí.

Notice the discrepancy of dates, though. Duchamp was already a practicing artist when the Great War broke out, Dalí still a child. By 1913 Duchamp was fed up of painting. Even as the cubists were inventing new perspectives, Duchamp had concluded that the tradition of Western painting was exhausted. In his studio in New York he experimented with alternative ways of making art.

Retinal versus Modern painting

Looking back from 1954, Duchamp wrote that after Impressionism the visual perception required by all art movements stopped at the retina: Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Abstraction they are all kinds of retinal art, meaning that they are concerned only with visual perception. He was impatient with this. A cerebral man, he wanted art with a bit more thought.

Later, in 1966, he recalled that just before the Great War the great thing was what the French call patte, meaning the hand, meaning the direct involvement of the hand in painting, the handiness, the imprint of the artist’s brushstrokes, a testament to the directness of artistic creation.

Again, Duchamp felt he was reacting against this peasant primitivism. He thought there should be a role for mind and reason and intellect in art. This is the context for his experiments with objects picked up in shops and the street, the so-called ‘readymades’. They and his other experiments were attempts to overthrow or go beyond the hand and retina in art, in fact to go beyond the entire Western tradition of the artist as a ‘maker’ or craftsman.

The earliest readymade was Bicycle wheel (1913), assembled from two parts, a bike wheel mounted on a stool. In time he came to call these ‘assisted readymades’ because they did require some intervention, as opposed to pure ‘readymades’ which are presented exactly as found.

Bicycle Wheel (1913, 6th version 1964) by Marcel Duchamp. Photo © Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada/© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

The first pure readymade i.e. an unchanged found object, was Bottle Rack (1914), an example of a mass-produced artefact owned by millions of French people. But this one had been selected and purchased by Duchamp, who indicated his intervention with a small inscription.

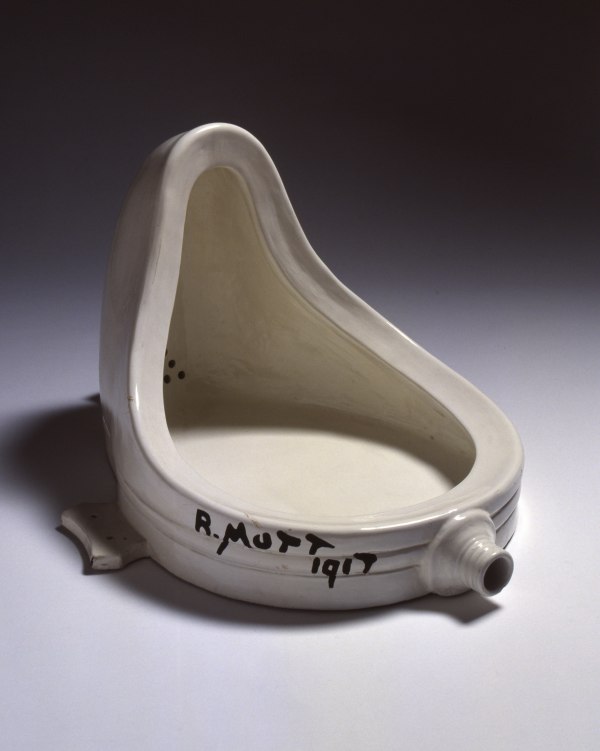

There’s a big display case in this exhibition which includes Bicycle wheel and Bottle rack and the most famous readymade of all, Fountain.

Fountain (1917, replica 1964) by Marcel Duchamp. Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art. Photograph © Schiavinotto Giuseppe/© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

Fountain (1917) is one of the icons of 20th century art, a mass manufactured urinal, placed untouched in a gallery except for the hand-written signature (in fact not Duchamp’s name, but one of his jokey, Dada alter egos, R. Mutt).

This begged the question, ‘What is a work of art?’ which people are still merrily asking to this day and will, forever. The practical answer is, ‘Anything a curator decides is a work of art and is worth buying and installing in a gallery’. Plenty of people think they’re artists and think they’re creating works of art and they and their friends and family might all agree – but only when a curator agrees, buys it, writes about it, displays it – does it enter the canon. Is it validated.

The commentary points out that the basic condition for choosing a readymade object was that Duchamp should remain aesthetically indifferent to it. He didn’t choose them because they’re beautiful. They’re not. The opposite: bicycle wheel, bottle rack, urinal.

The whole idea of the readymade was to get rid of taste, to dispense with the cult of the patte, the Artist’s Holy Hand.

The great irony is that it didn’t, did it? The Abstract Expressionists made a fetish of the visibility of the artist’s every gesture and stroke, and Jasper Johns – subject of a massive retrospective right next door to this exhibition – included hand prints in numerous paintings.

Duchamp’s readymades invented a place where artists (and viewers) can go, and gave rise to vast oceans of Conceptual Art. But it didn’t overthrow conventional art in the slightest. It just added a new wing to the old building.

The curators claim that these readymades ‘operate in a no man’s land between art and life’, which I thought was amusing.

a) Note the grandiose rhetoric

– ‘operate’ making them sound like secret agents, ‘no man’s land’ makes the whole thing sound like a World War One battlefield instead of a genteel, upper-class gallery.

b) They emphatically don’t. They are unmistakably works of art. I can tell because they are hanging in an expensive art gallery and, if I touched any of them, I would be warned, if I tried to take a photograph (banned) I would be told off, and if I walked off with one of them I would be arrested.

c) I.e. there can be no doubt whatsoever that they are extremely rare, precious and valuable works of art.

L.H.O.O.Q.

Less imposing is his 1919 work, L.H.O.O.Q. It’s a cheap postcard of the Mona Lisa on which Duchamp drew a moustache and beard.

It’s not exactly difficult to copy or reproduce, which is part of the point. Duchamp went on to produce numerous variations and version, including one with no beard or moustache and wittily titled L.H.O.O.Q. shaved.

I didn’t realise that the apparently obscure title has a simple explanation. When you say the French letters out loud they sound like ‘Elle a chaud au cul’, a slang expression literally meaning ‘She is hot in the arse’, or ‘she’s on heat’. The Mona Lisa was one of the jewels in the collection of Western art in the Louvre, venerated by the French bourgeoisie as embodying everything noble about French civilisation. So this wasn’t a small insult but a calculated subversion of an entire set of values.

This kind of shocking the bourgeoisie is what attracted both Dada and Surrealist artists to Duchamp. Dalí later wrote that L.H.O.O.Q was a fitting end-point to Western art. Except it wasn’t. The curators – with a kind of thumping inevitability – claim it is a work which questions ‘ideas of originality and authenticity and gender’.

Rrose Sélavy

This habit of schoolboy punning also explains the name he gave to his female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. At various points Duchamp dressed in women’s clothes, put on make-up, attended functions or had himself photographed as this severe Parisian lady.

Again, if you pronounce the name slowly in French it has another meaning – ‘Eros, c’est la vie’, which translates as ‘Eros, that is life’, or more simply, Love is life, the love in question having a strong sexual overtone.

Duchamp’s distance

Although Duchamp spent the First World War in New York, news of his work spread among the Dada movement in Europe. He never joined the group but was admired for his anti-art stance – an admiration carried on into the Surrealist movement, founded by many of the former Dadaists.

However, Duchamp never joined the Surrealists either, though he became friends with many of them, as the photos by Man Ray suggest. He was probably too rational and controlled to join a movement which is all about the irrational and automatic. Nonetheless, the leader of the Surrealists Andre Breton saw Duchamp’s readymades as the first Surrealist objects and included them in an exhibition with that title.

Surrealism didn’t get properly going until the Surrealist manifestos were published in 1924. By that time Duchamp had cultivated the idea that he had abandoned art altogether in order to play chess professionally. This was far from the truth, as he continued making works of art well into the 1960s – but for most of this period Duchamp was the hidden man and when he was tracked down and interviewed, was very quiet, modest and sane.

The opposite of Salvador Dalí. Dalí enthusiastically entered into the spirit of Surrealism and in 1931 came up with the idea of the ‘Object of Symbolic Function’, an object which supposedly epitomises Surrealist ambitions of bringing unconscious dreams, desires, fantasies into the real world. A good example was his Aphrodisiac Jacket (1936), an ordinary dinner jacket with liqueur glasses sown into it.

Dalí’s discovers the inclined plane

Dalí was young. He came to all this late. He was 10 when the Great War broke out, 12 when Dada was formed, 14 when Duchamp made Fountain, and just turning 20 when the first Surrealist manifesto was written and published by the leader of the group, poet André Breton.

After the early experiments – the father portrait, messing about with Cubism – it was news to me that at the tender age of 24 Dalí considered abandoning painting altogether, declaring that the future lay in photography and film.

He wasn’t wrong but film and photography didn’t work out, so he returned to painting in 1929 with a work which broke with his previous pieces. It introduced an unrealistically smooth, deep, perspective on which he could sit all kinds of incongruous objects.

The First Days of Spring (1929) by Salvador Dali. Collection of the Dali Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida. © Salvador Dali, Fundacia Gala-Salvador Dali, DACS 2017

Apparently, this painting also contains elements of collage and textures included in it. But the blindingly obvious components are the huge, empty, sweeping plain conceived as a stage for realistically depicted figures and objects undergoing strange transformations or caught in peculiar alienated poses.

He had invented an entire aesthetic which he would mine for the next 50 years or so, which led to the production of hundreds of variations, including some later masterpieces included here.

Nonetheless, in a revealing comment his friend Man Ray said that Dalí didn’t really like painting and would have much preferred to be a photographer. Although his paintings are dominated by soft-edged, often melting, forms, it’s worth bearing in mind this comment, and rethinking his paintings as settings of objects which have been arranged and staged as if for a photograph.

Sex

Both men were heterosexual males and had lifelong obsessions with sex and the female body, Duchamp in a generally discreet way, Dalí in an unembarrassed, flaunting way.

Here is Duchamp, just before he packed in painting, doing nudes. As you can see he is far more interested in the idea of movement, trying to capture movement in art, than in tits and bums (this phrase is taken from the title of the 1973 Monty Python book, Tits n’ Bums: A Weekly Look at Church Architecture, featuring articles such as ‘Are you still a verger?’)

The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912) by Marcel Duchamp. Philadelphia Museum of Art © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

The curators call this section of the show ‘The Body as Object’, which is a typically curatorspeak way of pussyfooting around the subject. It includes pretty silly works by Duchamp, such as a plaster cast of a woman’s labia, and another sculpture which appears to be a jockstrap. Allegedly, Duchamp was interested in the erotic, but you wouldn’t really have guessed.

On display are sketches and preparatory work for his last great piece, Étant donnés (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas, French: Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage) which he worked on from 1946 till 1966 and wasn’t finally displayed until after his death, in 1969. It consists of a tableau, visible only through a pair of peep holes (one for each eye) in a wooden door, of a nude woman lying on her back with her face hidden and legs spread holding a gas lamp in the air in one hand against a landscape backdrop.

Not very erotic is it? More of a disturbing image. I’ve read the suggestion that the body is a corpse and the whole thing is a crime scene, but then how is it holding a lamp up? Certainly the body has a cold, lumpen appearance more like a corpse than a sex object.

Meanwhile, in sunny Spain, Dalí luxuriated in the erotic. He was often at the beach with his smiling wife, Gala. Photos of them at the beach show a handsome couple: she was good looking, but he was gorgeous.

Dalí had no inhibitions when it came to showing the erotic, or the pornographic, in art. Thus the show includes several versions of a sketch of Dalí ‘eating’ a figure of Gala while masturbating – which come to a head in a vivid painting titled William Tell and Gradiva. Near to it is a lovely ink-and-pencil drawing of two full length women in billowing gowns titled Gradiva, one among numerous examples here of what a bewitching draughtsman Dalí could be.

The name Gradiva rang a bell. I knew that Gradiva is a novella by the German writer Wilhelm Jensen which was made the subject of a 1908 essay by Sigmund Freud. Freud used it to give a detailed example of how his theory of psychoanalysis could be applied to unearth buried themes and ideas in literature, beginning the process whereby Freudian psychoanalysis would go on to become a major thread of literary criticism.

But I didn’t know that Gradiva was a nickname Dalí gave his wife, Gala – so these Gradiva paintings and sketches are very autobiographical. Nor that other Surrealists featured Gradiva in their paintings and that she became so much of a muse to various Surrealists that, when the Surrealist writer André Breton opened an art gallery on the Rive Gauche, 31 rue de Seine in 1937, he gave it the name the Gradiva Gallery. Nor that the iconic door into the gallery was designed by Duchamp.

That’s a lot of context to take in and appreciate for one painting and a few sketches.

The importance of context

Which leads into one of the biggest conclusions I drew from the exhibition, which is the importance of the intellectual and historical context of these works.

Alongside the paintings and sculptures and readymades are quite a few display cases showing magazine articles, newspaper pieces, manifestos, books, essays, catalogues, letters, notes and sketches and diagrams and post cards relating to them. Dalí wrote essays about Duchamp. Duchamp wrote manifestos and essays about his own work. Dalí wrote lengthy books of theory. That’s jungle enough.

But both of them were also surrounded by complex networks of other artists all clamouring about their own work, jostling for position, launching volleys of provocations and reams of interpretations.

As the hand-out makes clear, Surrealism was to begin with a movement of artists and poets – of writers. It was only later that visual artists got involved, which explains the time lag between the first Surrealist manifesto of 1924 and the dating of many Surrealist art classics to the 1930s.

My point is that all these works were conceived and created amid a tremendous tangle of texts, articles and manifestos, declarations of principles and aims and goals all of which have fallen away like flesh from a carcass, leaving the works stranded in the antiseptic space of these display cases, hanging from the white walls of the gallery like the bare bones of a whale on the beach.

These works have then been reconstituted, rehung, reintroduced and retold to fit contemporary concerns, interests and rhetorics, to reflect the interests, language and rhetoric of the modern world and contemporary academic discourse – the all-too-familiar ‘issues’ of gender, identity and desire, which almost all art – no matter what it looks like – turns out to be addressing in the view of modern curators.

The manifestos and other paperwork, which made sense of the works in their time, are certainly on display here, but you can’t really read them and you certainly can’t turn over the pages. In effect, unintentionally, they are censored. Only the snippets which support curatorial aims are cut and pasted into the curatorial discourse in which the works are embedded.

I think this partly accounts for the tremendous sense of loss which hangs round the works, especially Duchamp’s.

There’s another level of loss or absence, prompted by the obvious thought that all these texts are in French, and all this creative thought and activity took place in French, in France, embedded in the density of French culture and history – all of which are very different from our Anglo-Saxon tradition.

1. Boobs

1. Take boobs. The French are not as hung up about women’s breasts as we are (something I realised when my parents took me on holiday to the South of France and I couldn’t believe the number of French women walking about topless as if they couldn’t care less).

- Picnic, Œle de Ste Marguerite, France, 1937 Photo by Roland Penrose showing Nusch Eluard, Paul Eluard, Lee Miller, Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin aka ‘Ady’

Compare and contrast the stress and neurosis surrounding women’s breasts in the Anglo-Saxon world, from the endless arguments about Page Three of the Sun to the contemporary ‘Free the Nipple’ movement to the fuss made about Janet Jackson’s top falling open to reveal her nipple during the 2004 Superbowl interval show.

Despite all efforts to the contrary, there continues to be something prudish, narrow-minded and uptight about the Anglo-Saxon attitude towards the naked human body.

2. France is a Catholic country.

From local curés to archbishops France’s official religious culture is more aggressively conservative and reactionary than our own ineffectual Church of England. This meant that desecration of religious imagery was hugely more significant in the French tradition. It also explains why the reaction to French Catholic culture and politics was that much more radical and extreme. The bitter opposition between Catholics and radicals has run through French politics and culture since the Revolution, through the Commune, the immensely bitter Dreyfus Affair, on into the tremendous power wielded by the French Communist Party during the 1930s and then in the decades after the second World War.

British politics and culture have just never been so polarised: we have an upper-class toff party or the party of timid trade unions to choose between. There have never been significant numbers of fascists or communists in Britain.

To summarise – these works have been subject to at least two translations:

- They have been surgically cleansed of all reference to the intellectual support system which gave rise to them

- And they have been translated from the intensely intellectual and more openly sexual atmosphere of France into the less reflective and more buttoned-up world of les Anglos

Texts

Anyway, back to texts. Duchamp was far the more cerebral of the two. He worked on the obscure and puzzling work, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, for eight years, from 1915 to 1923. The original was lost long ago but was reconstructed from photos and diagrams by Pop artist Richard Hamilton, and his reconstruction can be seen in Tate.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915, 1965 to 1966 and 1985) by Marcel Duchamp (reconstruction By Richard Hamilton) Photo © Tate, London, 2017/© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

It is symptomatic, though, that Duchamp intended this big sheet of glass to be accompanied by The Green Box, a collection of texts, diagrams and explanatory notes. These are here, in a display case, but they aren’t really readable, or very much explained.

I experienced a profound sense of missing the point, as with several other Duchamp pieces in this room. Clearly something intense, carefully planned and important is going on. It took long enough to make, after all. But what and why? I’m guessing that some kind of pamphlet-length explanation is required, hence Duchamp’s wish for accompanying texts and explanations. In the absence of really detailed text or guide these odd works sit abandoned and inscrutable.

This is the exact opposite of Dalí’s paintings. The examples of his mature work in the final room as dazzling in their fluency, inventiveness and power. They were so widely reproduced and available in my boyhood, so much of the poster-world of art’s greatest hits, that it’s easy to take them for granted – but a work like St John is absolutely stunning, a huge towering presence, surely a masterpiece.

Christ of Saint John of the Cross (c. 1951) by Salvador Dali. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Optical illusions

The exhibition suggests they shared an interest in optical illusions. Hence the nude-in-motion paintings right at the start of Duchamp’s career. Hence the clever use of contradictory or paradoxical perspective schemes in the upper and lower part of Dalí’s St John crucifixion.

The exhibition also includes a number of very hand-made, amateurish panopticons or look-through-the-little-slots-at-a-fantasy-landscape pieces which Duchamp constructed, all of which can be seen as preparation for the puzzling final work, Étant donnés which has to be observed through a peephole.

Dalí’s experiments with perspective and other optical illusions are a key element in his paintings, as in another masterpiece in the show.

Chess

Duchamp loved chess. He spread the rumour in the mid-1920s that he had abandoned art altogether in order to concentrate on playing chess professionally (could you really make a living from just playing chess in the 1925?). A display case lingers on his love of the game, and features both the early chess set that Duchamp himself used and a later, surreal one, made by Dalí, in which the pieces are mouldings of fingers, fingertips for the pawns, the whole finger wearing crowns for the king and queen but, unexpectedly, salt cellars for the rooks.

Chess boards and pieces appear in numerous surrealist paintings. Chess is to European art what poker is to American culture, a kind of central reference point which epitomises the culture, thoughtful European intellectuals on the one hand, Wild Western rednecks ready to pull out a gun at the drop of a hat in the violent States.

Apart from all its other elements, chess is a study of time and movement. On reflection you can see that its highly stylised moves continue Duchamp’s abiding interest in movement and motion. In the small room devoted to the chess pieces, as well as related artefacts, there’s a video playing in which Duchamp explains the aesthetic interest of chess.

He declares that a shot of the chess board at any one moment isn’t particularly interesting. What is interesting is that the pieces are locked into moving in a limited number of technically restricted ways. Thus something about the idea of a game, the idea of the movement of a finite number of pieces according to strict rules of movement but through a potentially infinite number of moves – that is beautiful, that can be a work of art.

It’s very winning to see the same anti-art, elliptical, sideways sensibility alive and well in the 70 year-old man as it was in the thirty year-old who created Fountain.

Films and TV

The commentary suggests that Dalí was the first celebrity artist of the TV age. His early interventions may have been in arthouse movies with Luis Bunuel but by the 1950s he was appearing on U.S. gameshows (‘What’s my Line?’) on TV specials, starring in documentaries and news reports made about him, generally milking the apparatus of celebrity for all it was worth. Thus the show includes a very entertaining selection of moving pictures featuring the old shyster, for example in this 1941 newsreel of a party Dalí designed and held in the Bali Room of the Hotel Del Monte, Monterey, California as a benefit for European artists.

The older Dalí appears in a clip titled ‘The Honorary Bullfight’, which appears to be a bullfight held in his honour in his native Spain, for which he had constructed a life-size model bull covered in gold plates. At the climax of the festivities it exploded in fizzing fireworks. Dalí bows grandly to the applauding crowd.

The most dramatic clip is the 90-second dream sequence which Dalí designed for the Alfred Hitchcock thriller about a possibly deranged psychiatrist, Spellbound.

Presence and prescience

The fifth and final room is more like a corridor back out into the main landing of the Royal Academy building. At the 1938 International Surrealism exhibition Dalí and Duchamp collaborated on the design and ‘scenography’. One room featured 1,200 coal sacks suspended from the ceiling over a stove. In this shortish corridor the curators have recreated the effect with 60 or more grubby full-seeming coal sacks bearing down from the ceiling and a row of small stoves lined up along the wall. It is intense and a bit suffocating.

Now, as it happens, last week I was at the Curve, the free exhibition space at the Barbican, to see an installation titled Purple by British artist John Akomfrah. Part of it was a narrow stretch of the gallery where he had suspended several hundred white plastic water cans from the ceiling, with white light beaming down through them. The effect was high, white and light like a sort of cathedral – as compared to the low, dark and oppressive effect of the coal sack ceiling.

The coincidence of a contemporary British artist doing something very very similar to – maybe deliberately referencing – a work created just about 80 years earlier made me reconsider a phrase from the wall label introducing the exhibition. Here are the curators:

What fuelled this seemingly unlikely friendship was deeper than their shared artistic interests – amongst them eroticism, language, optics and games. More fundamentally, the two men were united by a combination of humour and scepticism which led both, in different ways, to challenge conventional views of art and life in ways that seem startlingly prescient today.

‘Startlingly prescient today’ suggests that they anticipated where we are, that their work is good because it anticipates our own wonderful achievements in art and culture, that the real place, the real achievement is here and they were lucky enough to anticipate it.

But there is a completely different way to read that phrase, to the effect that we are still living in the world they created; we have progressed no further in our art and imaginations than the ‘imaginarium’ which these dead artists conceived all those years ago.

Bizarre objects, visionary paintings, experimental films, overt erotica, naked women and masturbating men, objects hanging from ceilings, the unashamed use of celebrity (Warhol, Jeff Koons), blatant commercialism (Damien Hirst), performance art, installations, non-conformist, anti-bourgeois, anti-repressive ‘provocations’ – by pushing their imaginations to the limit, these guys invented all the apparatus of contemporary art nearly a century ago – and it is where we still live, imaginatively.

We are still inhabiting the territory they opened up and repeating the works, ideas and antics they got up to all that time ago.

In the coal sack ceiling room I chatted to another visitor. She really liked a photo of Duchamp playing chess with a young woman. When I mentioned this to my wife she said, ‘Let me guess – the young woman is naked’. Yes. It is as entirely predictable as that. An old man, fully-clothed, is sitting opposite an attractive young woman, completely naked.

What my fellow visitor liked was the sense that the photo represented the 1960s with its exciting new world of happenings and love-ins and non-conformity and rebelliousness, and that the quietly spoken, chastely dressed, old man, Duchamp, had lived to see it happen. She thought it was strangely moving that his (artistic) grandchildren were flourishing and developing all kinds of ideas which he had invented. As they still are, today.

Video

There are several videos supporting the exhibition, including this quick snapshot from the RA’s artistic director, Tim Marlow.

Related links

- Dalí/Duchamp continues at the Royal Academy until 3 January 2018

Newspaper reviews

- Guardian review by Jonathan Jones

- Guardian review by Laura Cumming

- Independent review by Michael Glover