Two things about this book:

- It is very academic and scholarly. I imagine its main audience is university students. It spends more time explaining the academic debates surrounding dates and discoveries and conflicting interpretations of the archaeological evidence than in presenting a clear narrative.

- Which makes you realise that this is a fast-moving field, with new discoveries being made all the time, and that these discoveries sometimes significantly alter our understanding of timeframes and influences. I picked up the second (1996) edition in a charity shop, but realise now I should have bought the fifth edition, from 2012, because knowledge about the subject is changing all the time.

Chronology

The book opens with a daunting chronological table which has six columns, one each for Central Mexico, Oaxaca, Gulf Coast, Maya Highlands, and Lowland Maya – and 10 rows indicating time periods from 1,500 BC onwards.

Apparently, early archaeologists named artefacts from around 600 AD ‘classic’ and the name, or periodisation, stuck, despite not really fitting with later discoveries, so that successive archaeologists and historians have had to elaborate the schema, to create periods named ‘Proto Classic’, and then, going back before that, ‘Formative’ – which itself then turned out to need to be broken down into Early, Middle and Late Formative. At the other end of the scale they suggested a ‘Post-classic phase’, but over time this also had to be fine-tuned to include Early Postclassic and Late Postclassic.

I found it a big challenge to remember all the dates. Roughly speaking 600 AD seems to be the height of Classic and the period 300-900 includes Early, Mid and Late Classic.

Geography

When you look at a map of all the Americas, Central America quite obviously links the United States and South America. But it’s not quite the simple north-south corridor you casually think of. When you really come to consider the area in detail you realise it is more of a horseshoe shape, with the Yucatan peninsula forming the second upturn of the shoe. So the spread of influences, architecture, language and other artefacts wasn’t north to south but more along a west-east axis.

The book takes you slowly and carefully through the art and archaeology of Mesoamerica in nine chapters:

- Introduction

- The Olmecs

- The Late Formative

- Teotihuacan

- Classic Monte Alban, Veracruz and Cotzumalhuapa

- The Early Classic Maya

- The Late Classic Maya

- Mesoamerica after the fall of the Classic cities

- The Aztecs

On the face of it the book is a history of the peoples and cultures which inhabited the region of central Mexico stretching across to the Yucatan Peninsula and down into modern-day Guatemala and Belize, with most of the focus on the architecture, sculpture, friezes, pottery and (rare) painting which they produced…

But in fact, alongside what you could call the main historical narrative, runs the story of the discoveries upon which all our knowledge is based, a sequence of archaeological finds and decodings of lost languages which have a disconcerting tendency to overthrow and revolutionise previous thinking on lots of key areas.

What I learned

There’s no point trying to recap the massive amount of information in the book. The key points I learned are:

Mesoamerica refers to the diverse civilizations that shared similar cultural characteristics in the region comprising the modern-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The area was in continual occupation from 1500 BC to 1519 AD when the conquistadors arrived, but with a continual flux of peoples, tribes or nations in each region, marked by the rise and fall of cities and entire cultures.

The geography of Mesoamerica is surprisingly diverse, encompassing humid tropical areas, dry deserts, high mountainous terrain and low coastal plains.

Many cultural traits were present in the earliest, archaic peoples, then continued right through all successive cultures, including:

- a bewildering pantheon of deities, often with multiple identities – two which appear in almost every culture are the storm/rain god and a feathered serpent deity; the Mexica called the rain god Tlaloc, and the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl

- similar architectural features, especially the importance of stepped pyramids, often with nine levels

- a ballgame which had special ‘courts’ built for it in all the major cities of all the different cultures

- a 260-day calendar

- clothes which were elaborate and featured huge head-dresses often of feathers, alongside body painting

The key peoples or cultures are the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Toltec, Mixtec, and Mexica (or Aztec).

But there is still a lot which is unknown. For example, Miler devotes a chapter to the spectacular remains at the city of Teotihuacan (see below) but explains that we don’t know, to this day, the name of the people who built it!

The Aztecs didn’t call themselves Aztecs, they called themselves Mexica. They spoke a language called Nahuatl, which is still spoken to this day by some Indian groups. There were as many as 125 languages spoken in this region over this period. Some cultures developed rebus writing, i.e. writing which used images of the thing described rather than collections of letters. These images went on to have multiple meanings, and are also called pictographic, ideographic, or picture writing.

The ballgame

Peoples across Mesoamerica, beginning with the Olmecs, played a ritual sport known as the ballgame. Ballcourts were often located in a city’s sacred precinct, emphasizing the importance of the game. Solid rubber balls were passed between players with the goal of hitting them through markers.

But it wasn’t what we think of as a sport. The game had multiple meanings, including powerful religious and cult purposes. It appears, from a number of carved stone reliefs, that war captives were somehow made to play the game before being ritually beheaded or tortured.

Carved panel, South Ballcourt, El Tajin. A loser at the ballgame is being sacrificed by two victors (at bottom right) while a third man looks on (far right). A death god descends from the skyband above to accept the offering. Late Classic.

Two calendars

The calendar and numbering systems were complex and elaborate, although based around astronomical events and periods. There’s much evidence that key buildings, including many pyramids, were built in line with astronomical events such as equinoxes. They developed two parallel calendars: a 260-day one and a 365-day one. The 260-day calendar was a ritual calendar, with 20 months of 13 days. It is first recorded in the sixth century BC, and is still used in some parts of Guatemala today for ritual divining.

Based on the sun, the 365-day calendar had 18 months of 20 days, with five nameless days at the end. It was the count of time used for agriculture. Every 52 years the two calendars completed a full cycle, and during this time special rituals commemorated the cycle.

Blood sacrifice

Blood seems to have played a central role in numerous cultures and cities. We know that the Aztecs prized prisoners taken during battle because they could tear out their beating hearts from their bodies to sacrifice to the gods. But there are also plentiful wall art, carvings and frescos showing people who aren’t captives drawing their own blood using a panoply of utensils: sometimes, apparently, in order to have religious visions.

Another theme is piercing the tongue, or even penis, with a needle, thread or rope, apparently for cult or religious reasons.

A carved lintel from a building at Yaxchilan depicts a bloodletting ritual. The king of Yaxchilan, Shield Jaguar II, is holding a flaming torch over his wife, Lady K’ab’al Xook, who is pulling a thorny rope through her tongue. Scrolls of blood can be seen around her mouth. (British Museum)

Visual complexity

But the single biggest thing I took from the book is the extraordinary visual complexity of many of the images from these varied cultures.

The big stone Olmec heads, and many examples of pottery, are simple and easy enough to grasp visually. But there are also thousands of frieze carvings, free-standing stelae, even a few painted frescos have survived, and just a handful of manuscripts written in pictogram style – and almost all of these display a bewildering visual complexity. Clutter. Their images are immensely busy.

This is a drawing of the carved decoration found on a stela (i.e. an upright freestanding carved stone) at the city of Seibal.

Most of the friezes and stela and many of the manuscripts show a similar concern to cover every inch of the space with very characteristic style that’s hard to put into words, apart from clutter. The figures are so highly embellished and the space so packed with ornate curvilinear decorations (as well as rows of rectangular glyphs, a form of pictogram) that I had to read Miller’s descriptions of what was going on quite a few times and work really hard to decipher the imagery.

In this and scores of other examples, it takes quite a bit of referring back and forth between text and illustration to decipher what Miller is describing. For example I would only know that a death god is descending in the Ball park frieze [above] because Miller tells me so.

In many of these Mesoamerican carvings, it is impossible to distinguish human figures from the jungles of intertwining decoration which obscure them.

So I was struck that, for most of the peoples of the region, their public art was so complex and difficult to read.

By contrast, pottery by its nature generally has to be simpler, and I found myself very drawn to the monumental quality of early Olmec pottery.

Many fully carved sculptures from later eras manage to combine the decorative complexity of the friezes with a stunningly powerful, monumental presence.

There is a class of objects known as hachas, named after the Spanish term for ‘axe’. Hachas are representations of gear worn in the ballgame and are a distinctive form associated with art from the Classic Veracruz culture, which flourished along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico between 300 and 900 AD.

A Hacha in the Classic Veracruz style. It would have had inlays of precious materials, such as jade, turquoise, obsidian or shell. Middle to Late Classic (500-900 AD)

In three-dimensional sculpture the addiction of interlocking curlicues works, but in almost flat carvings or reliefs it can be impenetrable.

Can you make out a human figure in the complex concatenation of interlocking shapes on this stela? (Clue: His right hand is gripping a circle about two-thirds up on the far left of the stone. Even with clues, it’s not easy, is it?)

Places

- Bonampak – Late Classic period (AD 580 to 800) Maya archaeological site with Mayan murals

- Cacaxtla – small city of the Olmeca-Xicalanca people 650-900 AD, colourful murals

- Cerros – small Eastern Lowland Maya archaeological site in northern Belize, Late Preclassic to Postclassic period

- Cópan – capital city of a major Classic period Mayan kingdom from 5th to 9th centuries AD

- Chichen Itzá – city of the Toltecs tenth century, site of the biggest ball park in Mesoamerica

- Cotzumalhuapa – Late Classic major city that extended more than 10 square kilometres which produced hundreds of sculptures in a notably realistic style

- *El Tajín – one of the largest and most important cities of the Classic era of Mesoamerica, part of the Classic Veracruz culture, flourished 600 to 1200 CE. World Heritage site.

- Iximché – capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonment in 1524, located in present-day Guatemala

- Izapa – large archaeological site in the Mexican state of Chiapas, occupied from 1500 BCE to 1200 AD

- Kaminaljuyú – big Mayan site now mostly buried under modern Guatemala City

- Mitla – the most important site of the Zapotec culture, reaching apex 750-1500 AD

- *Monte Alban – one of the earliest cities of Mesoamerica, the pre-eminent Zapotec socio-political and economic centre for a thousand years, 250 BC – . Founded toward the end of the Middle Formative period at around 500 BC to Late Classic (ca. AD 500-750)

- Oxtotitlan – a rock shelter housing rock paintings, the ‘earliest sophisticated painted art known in Mesoamerica’

- *Palenque – Maya city state in southern Mexico, date from c. 226 BC to c. AD 799, contains some of the finest Mayan architecture, sculpture, roof comb and bas-relief carvings

- Piedras Negras – largest of the Usumacinta ancient Maya urban centres, known for its large sculptural output

- Seibal – Classic Period archaeological site in Guatemala, fl., 400 BC – 200 AD

- Tenochtitlan – capital city of the Aztecs, founded 1325, destroyed by the conquistadors 1520, now buried beneath Mexico City

- *Teotihuacan – vast city site in the Valley of Mexico 25 miles north-east of Mexico City, at its height 0-500 AD, the largest city in Mesoamerica population 125,000. A World Heritage Site, and the most visited archaeological site in Mexico.

- Tikal – one of the largest archaeological sites and urban centres of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, located in northern Guatemala. World Heritage Site.

- Tlatilco – one of the first chiefdom centres to arise in the Valley of Mexico during the Middle Pre-Classic period, 1200 BCE and 200 BCE, gives its name to distinctive ‘Tlatilco culture’.

- Tula – capital of the Toltec Empire between the fall of Teotihuacan and the rise of Tenochtitlan. Though conquered in 1150, Tula had significant influence on the Aztec Empire. Associated with the cult of the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl.

- Tulum – Mayan walled city built on tall cliffs along the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, one of the last cities built and inhabited by the Maya, at its height between the 13th and 15th centuries.

- Uaxactún – an ancient sacred place of the Maya civilization, flourished up till its sack in 378 AD

- *Uxmal – ne of the most important archaeological sites of Maya culture, founded 500 AD, capital of a Late Classic Maya state around 850-925, taken over by Toltecs around 1000 AD. World Heritage Site.

- Yaxchilán – Mayan city, important throughout the Classic era, known for its well-preserved sculptured stone lintels and stelae bearing hieroglyphic texts describing the dynastic history of the city.

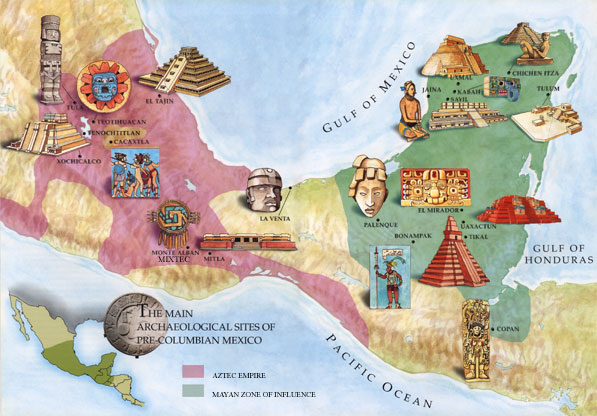

Another map, with pictures

Map of Mesoamerica showing the most important cities and historical sites. Red shading shows the area of Aztec influence, green shading for the Maya region

PBS Documentary

The sense of a double narrative – the way we not only learn the history of the Mesoamericans, but also the history of how we found out about the Mesoamericans – is well captured in this American documentary.