In August 1878, driven to distraction by the absence of his American lover, Fanny Osbourne, who had returned to California to patch things up with her estranged husband – Stevenson decided he could take no more of the emotional uncertainty in their relationship and, telling only his closest friends, bought a ticket on a transatlantic steamer from Glasgow to New York, planning to travel on to California to comfort and/or confront her.

The Amateur Emigrant describes in detail the transatlantic part of the trip, the journey by steamship from Glasgow to New York. This book picks up the second part – the train journey across America from New York to San Francisco. On Monday 18 August 1878 Stevenson took a river boat from New York to Jersey City, New Jersey, boarded the train and began the journey to California.

It is a shame for contemporary readers that these books didn’t all come out in chronological order or as he wrote them. Instead, The Amateur Emigrant wasn’t published till after Stevenson’s death, in 1895 (because of his family’s opposition to the image it painted of their boy slumming it with the roughest of the rough in steerage class) and Across the Plains was bundled up into a collection of miscellaneous writings, edited by his friend Sidney Colvin and only published in 1892, when Stevenson’s style and subject matter had moved far beyond it.

Across The Plains

You can tell that Stevenson was exhausted by now: the transatlantic journey had in reality been more gruelling than the Amateur Emigrant – for the most part buoyant, good-humoured and insightful – had implied.

In this book, for the first time, he seems to be failing in health and spirits, he feels oppressed, there are five bad experiences for every good one, and half way through the journey he actually falls ill, with no one to care for him. According to Claire Harman’s biography, when he finally arrived in Sacramento on the doorstep of his beloved Fanny, he looked like death, no longer the dashing blade who had charmed her at the artists’ colony in Barbizon two summers earlier, but a ragged, smelly, walking skeleton.

Things get off to a bad start as the emigrants squeeze into the emigrant shed in West Street, New York before being hustled down to the docks in the pouring rain. Several emigrant boatloads have docked in the city over the course of a few days, whereas no trains have left during that time, so all the facilities, waiting rooms, luggage areas and so on, are painfully packed. The ferry to New Jersey is wet and so over-crowded it leans to one side in the water.

The train is packed and uncomfortable, there is no food to be had apart from nuts and oranges, the hard wooden carriage benches are too narrow for two people to sit comfortably together and everyone smells like wet dogs.

It takes some time to get clear of the East Coast and into Pennsylvania, trying to sleep and being jostled awake again by rude neighbours or the rattling of the train. It’s a short book; you can read it in a couple of hours. Highlights for me include:

American sunsets

He finds American sunsets strikingly different from what he’s used to.

And it was in the sky, and not upon the earth, that I was surprised to find a change. Explain it how you may, and for my part I cannot explain it at all, the sun rises with a different splendour in America and Europe. There is more clear gold and scarlet in our old country mornings; more purple, brown, and smoky orange in those of the new. It may be from habit, but to me the coming of day is less fresh and inspiriting in the latter; it has a duskier glory, and more nearly resembles sunset; it seems to fit some subsequential, evening epoch of the world, as though America were in fact, and not merely in fancy, farther from the orient of Aurora and the springs of day. I thought so then, by the railroad side in Pennsylvania, and I have thought so a dozen times since in far distant parts of the continent. If it be an illusion it is one very deeply rooted, and in which my eyesight is accomplice.

Afro-Americans

He came ready to be shocked and full of pity for the poor downtrodden negro of liberal myth, and so was disconcerted that the first few blacks he met in America were confident hotel staff who almost looked down on him as a stranger to their cities and country.

I had come prepared to pity the poor negro, to put him at his ease, to prove in a thousand condescensions that I was no sharer in the prejudice of race; but I assure you I put my patronage away for another occasion, and had the grace to be pleased with that result.

He only meets two or three Afro-Americans and is impressed in each case by their self-possession and dignity. 140 years later American has, of course, solved all its issues around black people and is a beacon of racial peace and harmony.

America and guns

In the mid-West a drunk sneaks onto the train. It takes a couple of stops for the conductor to discover him but, when he does, the conductor manhandles the guy off the train (which is moving slowly through a siding). The man isn’t harmed, leaps to his feet and pulls a gun out of his belt.

It was the first indication that I had come among revolvers, and I observed it with some emotion. The conductor stood on the steps with one hand on his hip, looking back at him; and perhaps this attitude imposed upon the creature, for he turned without further ado, and went off staggering along the track towards Cromwell followed by a peal of laughter from the cars. They were speaking English all about me, but I knew I was in a foreign land.

Luckily, 140 years later, America has completely sorted out its problems with guns.

Rude and cramped

He finds a lot of Americans a strange combination of the rude and the sentimental. There are few public announcements about the trains’ movements and timetable and, since the emigrants are at the bottom of the train food chain, Stevenson gets used to their train spending interminable hours in sidings and being shunted to one side to let the important expresses whizz past.

The conductors are rude and surly: one memorably simply refuses to answer a question Stevenson puts to him point blank. All the emigrants know is that, when the train has stopped and they’re ranged about the siding, some eating, some half stripped off to wash, at any moment there might be a shout of ‘All aboard’, and the train will begin to move off, and they’ll all have to drop everything or throw food and toiletries into bags and scramble back aboard as best they can.

In the absence of public announcements the newsboys, who sell newspapers, fruit and nuts, become a vital contact with the outside world, but these are also often crude and rude, one of them kicking Stevenson’s long legs out of his way every time he goes up or down the carriage.

Size and scale

Stevenson finds the size and scale of the country dispiriting. There’s a ‘chapter’ (or short section) called The Plains of Nebraska which is just long enough for him to give a good sense of being frightened of the endless flat featureless plains which spread out in all directions – ‘a world almost without a feature; an empty sky, an empty earth; front and back, the line of railway stretched from horizon to horizon, like a cue across a billiard-board’.

He has a harrowing vision of how appalling it must have been for the first settlers who moved for days and days and days at oxen pace across the plains and never saw any feature or thing of interest to mark their progress. How dispiriting.

The desert of Wyoming

He knows the hills are coming and hopes they will provide a respite from the despair of the plains, but –

I longed for the Black Hills of Wyoming, which I knew we were soon to enter, like an ice-bound whaler for the spring. Alas! and it was a worse country than the other. All Sunday and Monday we travelled through these sad mountains, or over the main ridge of the Rockies, which is a fair match to them for misery of aspect. Hour after hour it was the same unhomely and unkindly world about our onward path; tumbled boulders, cliffs that drearily imitate the shape of monuments and fortifications – how drearily, how tamely, none can tell who has not seen them; not a tree, not a patch of sward, not one shapely or commanding mountain form; sage-brush, eternal sage-brush; over all, the same weariful and gloomy colouring, grays warming into brown, grays darkening towards black…

Mile upon mile, and not a tree, a bird, or a river. Only down the long, sterile cañons, the train shot hooting and awoke the resting echo. That train was the one piece of life in all the deadly land; it was the one actor, the one spectacle fit to be observed in this paralysis of man and nature…

Stevenson’s negativity is surprising. Nowadays super-real photos of the Rockies feature as computer screensavers or in cool movies about cruising through the astonishingly picturesque mountains. His negative response made me think that this whole huge area of America – like the desert which he describes later – only really became picturesque once you could travel freely through it in a car, not on foot. From the 1930s, say, you could drive out to these places, stay a night or two in a lodge or camp – and at any time drive back out of them, quickly and easily.

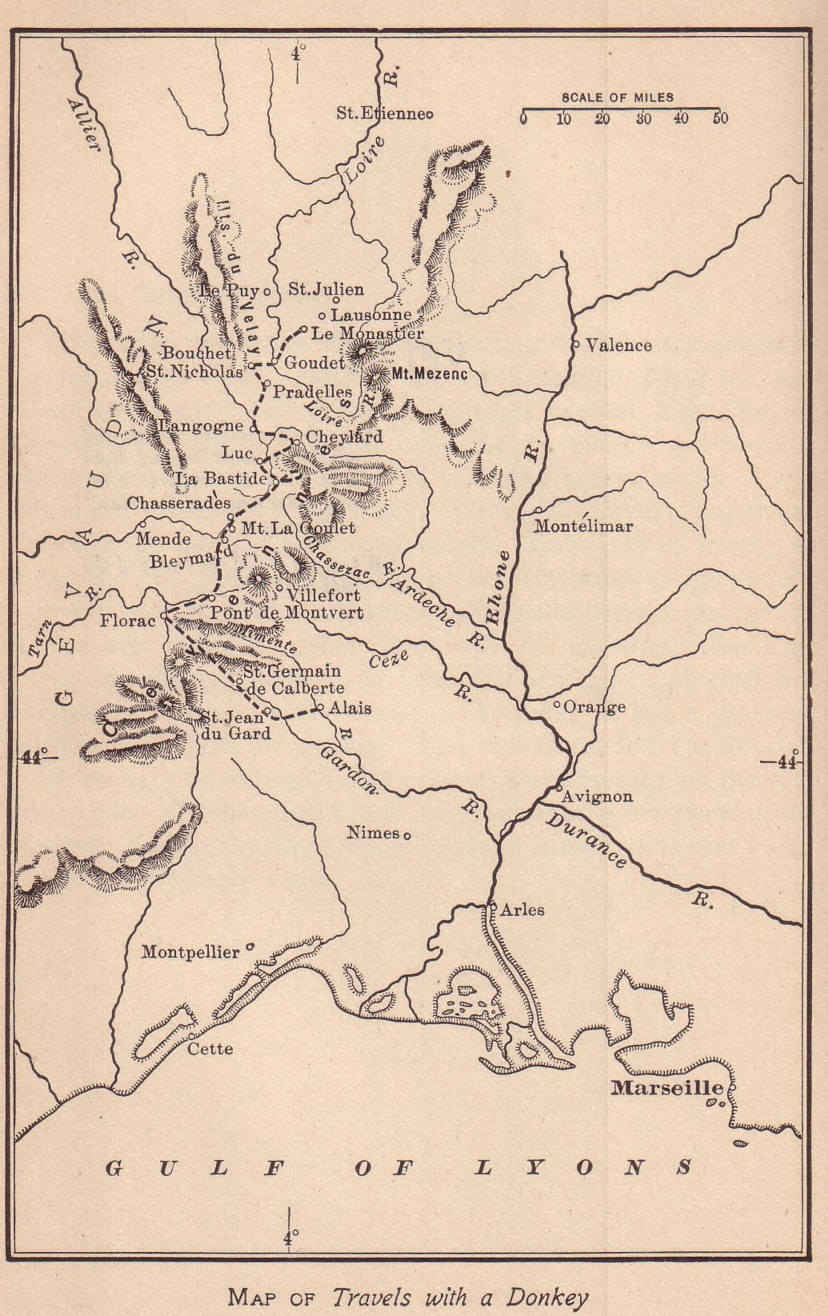

To someone used to walking – as Stevenson had just been walking in south-central France – and so used to the small-scale pleasures of copses and shaws and streams and dingles – the vast extent of the endless plains – and then the barren rockiness of the immense mountains – is truly horrifying. Imagine being lost there. You’d die far from any water, trees or shade, let alone human habitation.

The desert

Finally, appalled by the plains, then by the barren mountains, Stevenson is further disheartened by the fierce desert.

From Toano we travelled all day through deserts of alkali and sand, horrible to man, and bare sage-brush country that seemed little kindlier, and came by supper-time to Elko… Of all the next day I will tell you nothing, for the best of all reasons, that I remember no more than that we continued through desolate and desert scenes, fiery hot and deadly weary.

He really didn’t like almost all the scenery he saw and, speaking as a fellow walker, as someone used to thinking about territory in terms of footfall and paces and hours of walking, I can only agree with him. Train through it, drive through it, fly over it, and the American West is astonishingly raw and beautiful. but imagine being dropped into it with just a bottle of water and told to walk – quelle cauchemar!

Emigrants as a group

His thoughts about his fellow emigrants are noticeably less charitable than when he was aboard the emigrant ship. more than before, he is forced to the conclusion that many of the emigrants are failures in life, alcoholics, stupid people, lazy people, all of them naively convinced that if they travel West a miracle will happen – that they will reach a place where their stupidity, laziness or alcoholism will be magically transformed and they will become as rich and worthy of respect, as they know – deep inside – is their due.

But they won’t. At the end of his analysis of the shortcomings of the emigrants, Stevenson throws off a far more profound observation. If you were looking for rational causes for the mass emigrations i.e. evidence that people really do change their characters in foreign lands, you would look in vain. By and large they continue to be failures wherever the are. No, it isn’t about wages and economics and jobs – the compulsion to travel is something deeper and far more primeval.

If, in truth, it were only for the sake of wages that men emigrate, how many thousands would regret the bargain! But wages, indeed, are only one consideration out of many; for we are a race of gipsies, and love change and travel for themselves.

Prejudice

Stevenson’s opinion of the emigrants sinks even lower when he considers their attitude towards the Chinese. The emigrant train was divided into three sections: one for white men, one for white women and children, and one for the Chinese (Chinese labourers having, of course, slaved away and died building the transcontinental railways).

Not only are the American conductors, officials and the emigrants generally rude or sometimes violent, but they display a wall of prejudice against the Chinese: Stevenson singles out the accusation the most vocal bigots make that the Chinese are filthy. Stevenson thinks this is almost funny, since he notes that the Chinese carriage was probably the cleanest and the Chinese most often to be seen washing as much of their body as was decent in the stations and sidings – unlike his filthy, stinking white companions. (Stevenson slips in mention of a white demagogue he hears, weeks later in San Francisco, calling on a crowd of whites to rise up and throw off the ‘oppression’ of the Mongolian, again marvelling at how stupid and ignorant this kind of rabble-rousing is.)

Luckily, there are no demagogic politicians appealing to racial stereotypes in America these days.

Native Americans

Displaying admirable, and for his day astonishingly liberal instincts, Stevenson also goes out of his way to feel sorry for the Americans’ gruesome treatment of native American Indians, the original owners of this ‘great’ land.

Another race shared among my fellow-passengers in the disfavour of the Chinese; and that, it is hardly necessary to say, was the noble red man of old story –over whose own hereditary continent we had been steaming all these days. I saw no wild or independent Indian; indeed, I hear that such avoid the neighbourhood of the train; but now and again at way stations, a husband and wife and a few children, disgracefully dressed out with the sweepings of civilisation, came forth and stared upon the emigrants. The silent stoicism of their conduct, and the pathetic degradation of their appearance, would have touched any thinking creature, but my fellow-passengers danced and jested round them with a truly Cockney baseness. I was ashamed for the thing we call civilisation. We should carry upon our consciences so much, at least, of our forefathers’ misconduct as we continue to profit by ourselves.

If oppression drives a wise man mad, what should be raging in the hearts of these poor tribes, who have been driven back and back, step after step, their promised reservations torn from them one after another as the States extended westward, until at length they are shut up into these hideous mountain deserts of the centre—and even there find themselves invaded, insulted, and hunted out by ruffianly diggers? The eviction of the Cherokees (to name but an instance), the extortion of Indian agents, the outrages of the wicked, the ill-faith of all, nay, down to the ridicule of such poor beings as were here with me upon the train, make up a chapter of injustice and indignity such as a man must be in some ways base if his heart will suffer him to pardon or forget.

Final relief

The bareness and sterility of the desert oppresses Stevenson almost as much as the stink of his unwashed companions and their brutal attitude to the Chinese or Indians. All combine to make the journey hellish and explain the excess of relief he feels when the train finally emerges into the wooded, watered scenery of the Pacific side of the Rocky Mountains.

It is a spiritual and emotional relief for Stevenson and for the reader – that this short book ends on this sudden up-beat note.

I sat up at last, and found we were grading slowly downward through a long snowshed; and suddenly we shot into an open; and before we were swallowed into the next length of wooden tunnel, I had one glimpse of a huge pine-forested ravine upon my left, a foaming river, and a sky already coloured with the fires of dawn. I am usually very calm over the displays of nature; but you will scarce believe how my heart leaped at this. It was like meeting one’s wife. I had come home again – home from unsightly deserts to the green and habitable corners of the earth. Every spire of pine along the hill-top, every trouty pool along that mountain river, was more dear to me than a blood relation. Few people have praised God more happily than I did.

Stevenson is always interesting and entertaining, but this is easily the most disillusioned and bleak of the four travel books I’ve read so far.

Related links

- Across The Plains on Project Gutenberg

- Across The Plains Wikipedia article

- Summary of Across The Plains on the RLS website

- Robert Louis Stevenson titles available online