This is an interesting and enlightening exhibition with plenty of good things in it, but which in parts is a little puzzling and frustrating.

Deep prehistory

The curators (John Giblin, Chris Spring and Laura Snowling) say they’re setting out to give an overview of the art of South Africa and this they certainly do with visual representations of every period of South Africa, beginning in the inconceivably distant past with a stone from a site inhabited by pre-humans some 3 million years ago. The experts think it was brought from some distance away because of its presumable similarity to a human face, and so indicates self-awareness in our remotest ancestors.

There’s a hand axe made by Homo ergaster, a predecessor of Homo sapiens, and dated to 1 million years ago – apparently, in fact, not that practical as an axe, but here to demonstrate that an aesthetic sense seems to have existed in our remotest ancestors.

There’s the Blombos Cave beads, created some 75,000 years ago, painted and pierced in order to be strung together as a necklace. There’s the Coldstream Stone from 9,000 years ago.

Coldstream Stone, ochre, stone (c. 7,000 BC) © Iziko Museums of South Africa, Social History Collections, Cape Town

And the beautiful Zaamenkomst Panel, cave paintings made between one and three thousand years ago.

Taken together, these wonderful objects give a powerful sense of South Africa as one of the origins not only of early humans but of the earliest art works.

Contemporary art

What’s a little confusing is that right from the start this very museum-y ancient history is mixed in with works by contemporary South African artists – a lot of works. It may be creative curating, but it means it’s quite a lot to take on board – the origins of our species, the ancient prehistory of the area, done rather quickly – while, at the same time, we’re trying to understand post-apartheid art which, by its nature, mixes African traditions with the confusing panoply of postmodern artistic techniques and assumptions.

Thus I can see that it’s clever to place Potent fields by Karel Nel (2002) next to the ancient cave paintings, since both use ochre as a colour and material. And the curators have put a tapestry, ‘The Creation of the Sun‘, made by artists at the Bethesda Art Centre, opposite the cave paintings to show the continuity of style and creativity from South Africa’s first peoples, the San|Bushmen and Khoekhoen, to their contemporary descendants. In these first rooms we also see:

- Taung Skull by Karel Nel – a digital treatment of the skull of an early human ancestor

- Cape of Good Hope by Penny Siopsis – Siopsis is white and her artworks appear to be drenched in the red blood of black victims of apartheid

Clever but… it demands quite a lot of the visitor to juggle all these different frames of reference.

Tone

Another slightly disorienting element is the rather patronising or simplistic tone of the commentary. Right at the start there’s a wall panel titled ‘Cradle of Humanity’, which points out that the prehistoric finds gathered here prove that humanity evolved in Africa and so that – contrary to Eurocentric narratives – we are all in a deep sense Africans. What puzzled me is that I’ve never thought otherwise, I’ve never read anywhere anywhere any alternative theory of human origins: all my adult life I’ve known that humans evolved from apelike ancestors in Africa, my children know that, everyone knows it. A quick search reveals that Darwin suggested it as long ago as 1871 in The Descent of Man. Who are they arguing with? If apartheid taught that humans evolved in some other place – like Holland – it would have been informative and funny to have read more about it.

Scattered throughout the exhibition are wall panels talking about the need to fight and counter apartheid ‘narratives’ about the ‘savagery’ of the blacks or their ‘lack of culture’ – all cast in the present tense, as if this is an ongoing struggle.

a) I was there in the 1980s when we all wore anti-apartheid badges, sang along to ‘Free Nelson Mandela‘ and ‘Biko‘, and boycotted South African products. I never met anybody who in any way defended apartheid. Looking around the visitors to the show, I don’t think there was much risk that any of them would defend ‘apartheid narratives’ about ‘savage’ blacks or the ‘lack of black culture’.

b) It was all such a long time ago. The apartheid regime collapsed in the early 1990s and free elections brought the ANC government to power in 1994, 22 years ago. Many of the wall panels give the impression the curators are still bravely fighting a battle which, in fact, ended a generation ago. My companion joked that maybe their next exhibition should be devoted to bringing down the Soviet Union.

Because of the interleaving of big and very varied works by contemporary artists I found the timeline of pre-colonial South African art a bit hard to follow. I got that the Bantu people spread across the region (which in fact I knew from Chris Stringer’s book The Origin of Our Species). There was a case of exquisite gold statuettes of African animals, including a golden rhino which, we were told, are from Mapungubwe, capital of the first kingdom in southern Africa (c. AD 1220–1290). Maybe I blinked and missed the follow-up information, but I would really have liked to learn much more about the rise of kingdoms and territories and language groups and cultures and traditions across this huge area.

Gold rhino from Mapungubwe, capital of the first kingdom in southern Africa (c. AD 1220–1290) Department of Arts © University of Pretoria. The golden rhino is now the symbol of the Order of Mapungubwe, South Africa’s highest honour that was first presented in 2002 to Nelson Mandela.

Maybe the history just isn’t there, I mean the written history that would allow that kind of detailed narrative to be constructed. There were a few display cases showing weapons – a big shield made of hide alongside spears – and another one containing traditional carved wood figures, including a really beautiful ‘stylised wooden figure’, examples of traditional beadwork and some striking traditional dresses.

But I felt slightly afraid of liking anything because the wall labels made quite a point, repeatedly, of emphasising how the European colonists from the first Dutch arrivals in the 1650s through to the end of apartheid in the 1990s, had in a whole host of ways denied the validity of pre-colonial art and culture, denying in fact that the land was inhabited at all or, if conceding that it was, then only by ‘savages’ who didn’t plough or reap, by non-Christians who needed to be converted, by violent tribesmen who needed to be pacified.

And that one of the ways the European colonists/imperialists/racists limited and controlled the native people was by defining their art and traditions as ‘exotic’, pigeonholing them as ‘primitive’, demeaning and debasing their traditions and achievements. Thus told off, I felt a little scared about ‘liking’ any of the pre-colonial art in case I was displaying an ‘ethnocentric’ and patronising taste for ‘the exotic’.

Xhosa snuffbox in the shape of an ox, South Africa (late 19th Century) © The Trustees of the British Museum

This unnerved me because some of my favourite objects in the whole British Museum are the wonderful bronzes of Benin, among the most complete and finished works of art I know of from anywhere – as well as the whole range of weird and wonderful and powerful fetishes, images and carvings in the Museum’s Africa galleries.

Contemporary art 2

Anyway, the main thing about this exhibition is that interwoven among the pre-colonial artefacts which you would normally associate with the British Museum, are the works of a large number of modern and contemporary South African artists, black and white, men and women. Hopefully we are freer to express an opinion about these without running the risk of being considered ethnocentric or Eurocentric.

Apparently, the Museum has been collecting contemporary South African art for some 20 years, since – in other words – the collapse of apartheid, the first free elections and the coming to power of Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress. This explains why so many contemporary artworks are threaded through the show right from the first room and why the later rooms are entirely full of what you’d call modern art.

Artists and works

- The Watchers by Francki Burger (2014) a photo montage of the site of the Battle of Spion Kop in the Boer War.

- Oxford Man by Owen Ndou.

- Pantomime Act and Trilogy by Johannes Phokela.

- The Battle of Rorke’s Drift by John Muafangejo.

- Butcher Boys by Jane Alexander (1986) not actually physically in the show, there is a vivid photo of it here.

- It left him cold – the death of Steve Biko (1990) by Sam Nhlengethwa.

- The Black Photo Album/Look at Me by Santu Mofokeng, who has spent years researching and retouching hundreds of black and white photographs commissioned by urban black working and middle-class families in South Africa between 1890 and 1950.

- Christ playing football by Jackson Hlungwani (1983).

- Candice Breitz’s extended video ‘Extras’, filmed on the set of a popular black soap opera, in which all the actors play out straight soap opera scenes except with the artist herself, blonde Candice, placed in bizarre stationary positions around the set. I laughed out loud when I read that it explores ‘an absent presence or a present absence’ – it’s good to know that Artbollocks is a truly international language.

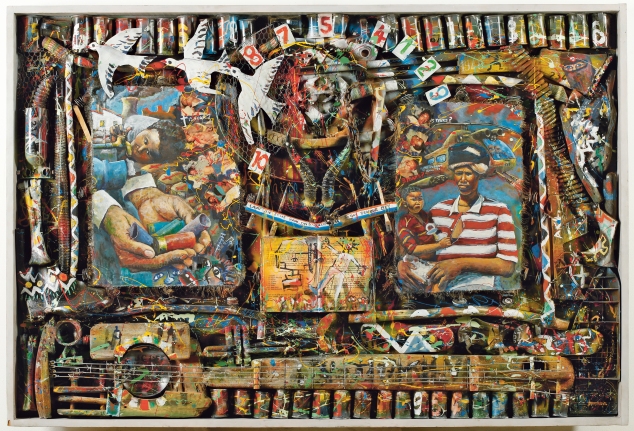

Willie Bester’s Transition (1994) commemorates seven children killed when security forces stormed a house supposedly occupied by terrorists. (See a video of the artist talking about it).

- A Reversed Retrogress: Scene 1 (The Purple Shall Govern) by Mary Sibande (2013) probably the biggest and most dramatic work here (see the video of Mary Sibande talking about this work).

- Reclamation by Lionel Davis (see the video of the artist talking about this work).

- Going Home by David Goldblatt (1989) one of a whole series the photographer took recording the long hours and hard lives of blacks under apartheid.

- Negotiations Minuet by William Kentridge.

South African timeline

It was difficult to grasp the ancientness of the earliest exhibits here, which wasn’t helped by their interspersion with bang up-to-date contemporary art. Apart from the gold animal statues from Mapungubwe (which I’d like to have learned more about), you got little sense of the region’s pre-colonial history. Many artefacts (carvings, weapons, figurines), yes; but a clear chronology with maps? Less so.

Purely from the point of view of being able to orient oneself in time and space, it was in many ways a relief to enter recorded, written history with the arrival of the Europeans and the (all-too-familiar) story of colonisation. The Portuguese made the first contacts in the 1490s, but it was the Dutch who built a settlement at Table Bay in the 1650s, as a stopover on the long sea voyages to their trading colonies in the East Indies. The British seized Cape Town from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars (1803 to 1815). It was this dual colonisation which explains why the country is English-speaking but with a large Dutch or Afrikaans minority, a minority the British went to war with twice, in the First Boer War (1880 to 1881) and the more famous second Boer War (1899 to 1902).

It was informative to learn how in the 19th century the British Empire imported labour from elsewhere in Africa and Asians from Indonesia and India, to work in South Africa. The exhibition includes one of the distinctive pointed hats worn by Chinese immigrants, as well as a pair of sandals the most famous Indian immigrant – Mahatma Gandhi – made for the country’s leader, General Jan Smuts, while he was in prison in 1913. Gandhi was to formulate many of the ideas in racist South Africa which he then took back to India to use in his campaign for independence.

As a language student I learned:

- That ‘Hottentot’ was a Dutch nonsense word meaning ‘one who stutters’, insultingly applied to the native blacks because of the use of click sounds in the San language. Hence it is a derogatory word which is not now used.

- That ‘Kaffir’, another derogatory term for blacks widely used in colonial times, derives from the Arabic for ‘unbeliever’.

- That ‘Boer’ derives from the Dutch word for ‘farmer’.

What I’ve never really understood and didn’t get any enlightenment about here, is the period between the First World War – when South Africa sent troops to fight alongside the British – and the end of the Second World War, when the foundations were laid by Nationalist governments for the system which would become apartheid. There were several rooms about the evils of apartheid and one about the end of apartheid, but I was left as ignorant as before about the origins of apartheid – about the economic, social and cultural forces which led to its creation, with the main milestones clearly marked out and explained.

Modern South Africa

The room full of images of the horror, violence and oppression of 1960s and 70s and 80s apartheid, with records of the Sharpeville Massacre (1960), the murder of Steve Biko (1977), a display case full of ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ badges and so on, felt very familiar to me from my school days in the 1970s and student days in the 1980s, when we all protested against apartheid, signed petitions, boycotted South African goods and so on.

As I viewed photos and artworks depicting the humiliations, poverty, incredibly long hours forced to work in menial jobs and the debasement and restrictions imposed on blacks by the apartheid state, I wondered whether the exhibition was going to dwell on the exploitation, the anger and the resistance of people during that era, and move on to cover the 25 years since Nelson Mandela was released, when things have got a lot less black and white.

For according to the newspapers, TV, documentaries and films which I consume, since liberation South Africa has developed into one of the most crime-ridden societies in the world, with just over 50 murders a day, and so many rapes that it has been called ‘the rape capital of the world, with one in four men admitting to having raped someone’.

At the same time South Africa is thought to have more people with HIV/AIDS than any other country in the world – 5.7 million, 12% of the population of 48 million. There was a small display case showing some dollies made in a traditional style which were a response to the AIDS epidemic by an artistic collective – but nothing about the era of ‘denialism’ under Thabo Mbeki (president from 1999 to 2008), who refused to accept the link between HIV and AIDS, and whose ban on antiretroviral drugs in public hospitals is estimated to be responsible for the premature deaths of between 330,000 and 365,000 people.

Contemporary South Africa today faces immense social, political, economic and medical challenges.

In the videos supporting the exhibition, the Museum curators make the point that this is quite a ‘political’ exhibition. That would have been the case if this was 1986 and voices could be found – in Mrs Thatcher’s Conservative Party, say, or the CIA – which defended the South African apartheid regime as a vital bulwark against Soviet-backed communism – but that was an era ago and it feels like they are fighting yesterday’s war.

Throughout the exhibition the curators criticise the Eurocentrism and racism of the colonists and the Imperialists and the founders of apartheid, who denied or denigrated black cultural achievements – as if this was still a battle being fought now; as if apartheid is still a flourishing regime which urgently needs challenging; as if unregenerate imperialist views about pre-colonial South African history are still widely held by lots of people.

In the exhibition, gold treasures of Mapungubwe will be displayed alongside a modern artwork by Penny Siopis and a sculpture by Owen Ndou that encourage the viewer to challenge the historic assumptions of the colonial and apartheid eras. (Press release)

Really? Does anyone even know what ‘the historic assumptions of the colonial and apartheid eras’ are, that are being challenged? In this respect it feels incredibly old-fashioned: the Us-versus-Them mindset made me nostalgic for my student days when international politics were so much clearer cut.

Meanwhile, back in 2017, the modern ‘struggle’ in South Africa is to formulate economic and social policies which will boost the economy and try to spread wealth and well-being out to the great bulk of the (black) population who have never seen the benefits of the end of apartheid and who are still mired in poverty and illness. A much harder ‘struggle’ because it is no longer so easy to identify the goodies and the baddies and, in fact, there may be no easy solutions.

Credit

Hats off to Betsy and Jack Ryan who sponsored the exhibition and to IAG Cargo who transported many of these objects from museums and galleries across South Africa. It’s a brilliant opportunity to see all kinds of works from South Africa, from the rarest prehistoric artefacts to bang up-to-date contemporary art. Maybe it’s my fault if I found so many complex histories and paradigms difficult to process in one visit.

The trailer

Museums and galleries are producing more and more videos to explain their exhibitions. The British Museum has set up a channel containing eight videos about this show.

I strongly recommend watching the videos before going to see the exhibition, as they explain the rationale for the layout, and prepare you for the emphasis on modern artworks, ahead of your arrival.

Related links

- South Africa: the art of a nation continues at the British Museum until 26 February 2017

Reviews

- Guardian review by Jonathan Jones

- Evening Standard review by Mathhew Collings

- Daily Telegraph article about the Museum’s South Africa art acquisitions