Chemistry is the science of changes in matter. (p.37)

At just under 150 pages long, A Journey Into the Land of the Chemical Elements is intended as a novel and imaginative introduction to the 118 or so chemical elements which are the basic components of chemistry, and which, for the past 100 years or so, have been laid out in the grid arrangement known as the periodic table.

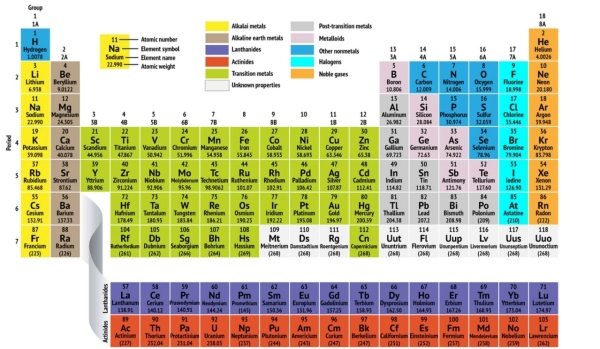

The periodic table explained

Just to refresh your memory, it’s called the periodic table because it is arranged into rows called ‘periods’. These are numbered 1 to 7 down the left-hand side.

What is a period? The ‘period number’ of an element signifies ‘the highest energy level an electron in that element occupies (in the unexcited state)’. To put it another way, the ‘period number’ of an element is its number of atomic orbitals. An orbital is the number of orbital positions an electron can take around the nucleus. Think of it like the orbit of the earth round the sun.

For each element there is a limited number of these ‘orbits’ which electrons can take up. Hydrogen, in row one, can only have one electron because it only has one possible orbital for an electron to take up around its nucleus. All the elements in row 2 have two orbitals for their electrons, and so on.

Sodium, for instance, sits in the third period, which means a sodium atom typically has electrons in the first three energy levels. Moving down the table, periods are longer because it takes more electrons to fill the larger and more complex outer levels.

The columns of the table are arranged into ‘groups’ from 1 to 18 along the top. Elements that occupy the same column or group have the same number of electrons in their outer orbital. These outer electrons are called ‘valence electrons’. The electrons in the outer orbital are the first ones to be involved in chemical bonds with other elements; they are relatively easy to dislodge, the ones in the lower orbitals progressively harder.

Elements with identical ‘valance electron configurations’ tend to behave in a similar fashion chemically. For example, all the elements in group or column 18 are gases which are slow to interact with other chemicals and so are known as the inert gases – helium, neon etc. Atkins describes the amazing achievement of the Scottish chemist William Ramsey in discovering almost all the inert gases in the 1890s.

Although there are 18 columns, the actual number of electrons in the outer orbital only goes up to 8. Take nitrogen in row 2 column 15. Nitrogen has the atomic number seven. The atomic number means there are seven electrons in a neutral atom of nitrogen. How many electrons are in its outer orbital? Although nitrogen is in the fifteenth column, that column is actually labelled ‘5A’. 5 represents the number of electrons in the outer orbital. So all this tells you that nitrogen has seven electrons in two orbitals around the nucleus, two in the first orbital and five in the second (2-5).

Note that each element has two numbers in its cell. The one at the top is the atomic number. This is the number of protons in the nucleus of the element. Note how the atomic number increases in a regular, linear manner, from 1 for hydrogen at the top left, to 118 for Oganesson at the bottom right. After number 83, bismuth, all the elements are radioactive.

(N.B. When Atkins’s book was published in 1995 the table stopped at number 109, Meitnerium. As I write this, 24 years later, it has been extended to number 118, Oganesson. These later elements have been created in minute quantities in laboratories and some of them only exist for a few moments.)

Beneath the element name is the atomic weight. This is the mass of a given atom, measured on a scale in which the hydrogen atom has the weight of one. Because most of the mass in an atom is in the nucleus, and each proton and neutron has an atomic weight near one, the atomic weight is very nearly equal to the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus.

Note the freestanding pair of rows at the bottom, coloured in purple and orange. These are the lanthanides and actinides. We’ll come to them in a moment.

Not only are the elements arranged into periods and groups but they are also categorised into groupings according to their qualities. In this diagram (taken from LiveScience.com) the different groupings are colour-coded. The groupings are, moving from left to right:

Alkali metals The alkali metals make up most of Group 1, the table’s first column. Shiny and soft enough to cut with a knife, these metals start with lithium (Li) and end with francium (Fr), among the rarest elements on earth: Atkins tells us that at any one moment there are only seventeen atoms of francium on the entire planet. The alkali metals are extremely reactive and burst into flame or even explode on contact with water, so chemists store them in oils or inert gases. Hydrogen, with its single electron, also lives in Group 1, but is considered a non-metal.

Alkaline-earth metals The alkaline-earth metals make up Group 2 of the periodic table, from beryllium (Be) through radium (Ra). Each of these elements has two electrons in its outermost energy level, which makes the alkaline earths reactive enough that they’re rarely found in pure form in nature. But they’re not as reactive as the alkali metals. Their chemical reactions typically occur more slowly and produce less heat compared to the alkali metals.

Lanthanides The third group is much too long to fit into the third column, so it is broken out and flipped sideways to become the top row of what Atkins calls ‘the Southern Island’ that floats at the bottom of the table. This is the lanthanides, elements 57 through 71, lanthanum (La) to lutetium (Lu). The elements in this group have a silvery white color and tarnish on contact with air.

Actinides The actinides line forms the bottom row of the Southern Island and comprise elements 89, actinium (Ac) to 103, lawrencium (Lr). Of these elements, only thorium (Th) and uranium (U) occur naturally on earth in substantial amounts. All are radioactive. The actinides and the lanthanides together form a group called the inner transition metals.

Transition metals Returning to the main body of the table, the remainder of Groups 3 through 12 represent the rest of the transition metals. Hard but malleable, shiny, and possessing good conductivity, these elements are what you normally associate with the word metal. This is the location of many of the best known metals, including gold, silver, iron and platinum.

Post-transition metals Ahead of the jump into the non-metal world, shared characteristics aren’t neatly divided along vertical group lines. The post-transition metals are aluminum (Al), gallium (Ga), indium (In), thallium (Tl), tin (Sn), lead (Pb) and bismuth (Bi), and they span Group 13 to Group 17. These elements have some of the classic characteristics of the transition metals, but they tend to be softer and conduct more poorly than other transition metals. Many periodic tables will feature a highlighted ‘staircase’ line below the diagonal connecting boron with astatine. The post-transition metals cluster to the lower left of this line. Atkins points out that all the elements beyond bismuth (row 6, column 15) are radioactive. Here be skull-and-crossbones warning signs.

Metalloids The metalloids are boron (B), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), arsenic (As), antimony (Sb), tellurium (Te) and polonium (Po). They form the staircase that represents the gradual transition from metals to non-metals. These elements sometimes behave as semiconductors (B, Si, Ge) rather than as conductors. Metalloids are also called ‘semi-metals’ or ‘poor metals’.

Non-metals Everything else to the upper right of the staircase (plus hydrogen (H), stranded way back in Group 1) is a non-metal. These include the crucial elements for life on earth, carbon (C), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), oxygen (O), sulfur (S) and selenium (Se).

Halogens The top four elements of Group 17, from fluorine (F) through astatine (At), represent one of two subsets of the non-metals. The halogens are quite chemically reactive and tend to pair up with alkali metals to produce various types of salt. Common salt is a marriage between the alkali metal sodium and the halogen chlorine.

Noble gases Colorless, odourless and almost completely non-reactive, the inert, or noble gases round out the table in Group 18. The low boiling point of helium makes it a useful refrigerant when exceptionally low temperatures are required; most of them give off a colourful display when electric current is passed through them, hence the generic name of neon lights, invented in 1910 by Georges Claude.

The metaphor of the Periodic Kingdom

In fact the summary I’ve given above isn’t at all how Atkins’s book sounds. It is the way I have had to make notes to myself to understand the table.

Atkins’ book is far from being so clear and straightforward. The Periodic Kingdom is dominated by the central conceit that Atkins treats the periodic table as if it were an actual country. His book is not a comprehensive encyclopedia of biochemistry, mineralogy and industrial chemistry; it is a light-hearted ‘traveller’s guide’ (p.27) to the table which he never refers to as a table, but as a kingdom, complete with its own geography, layout, mountain peaks and ravines, and surrounded by a sea of nothingness.

Hence, from start to finish of the book, Atkins uses metaphors from landscape and exploration to describe the kingdom, talking about ‘the Western desert’, ‘the Southern Shore’ and so on. Here’s a characteristic sentence:

The general disposition of the land is one of metals in the west, giving way, as you travel eastward, to a varied landscape of nonmetals, which terminates in largely inert elements at the eastern shoreline. (p.9)

I guess the idea is to help us memorise the table by describing its characteristics and the changes in atomic weight, physical character, alkalinity, reactivity and so on of the various elements, in terms of geography. Presumably he thinks it’s easier to remember geography than raw information. His approach certainly gives rise to striking analogies:

North of the mainland, situated rather like Iceland off the northwestern edge of Europe, lies a single, isolated region – hydrogen. This simple but gifted element is an essential outpost of the kingdom, for despite its simplicity it is rich in chemical personality. It is also the most abundant element in the universe and the fuel of the stars. (p.9)

Above all the extended metaphor (the periodic table imagined as a country) frees Atkins not to have to lay out the subject in either a technical nor a chronological order but to take a pleasant stroll across the landscape, pointing out interesting features and making a wide variety of linkages, pointing out the secret patterns and subterranean connections between elements in the same ‘regions’ of the table.

There are quite a few of these, for example the way iron can easily form alliances with the metals close to it such as cobalt, nickel and manganese to produce steel. Or the way the march of civilisation progressed from ‘east’ to ‘west’ through the metals, i.e. moving from copper, to iron and steel, each representing a new level of culture and technology.

The kingdom metaphor also allows him to get straight to core facts about each element without getting tangled in pedantic introductions: thus we learn there would be no life without nitrogen which is a key building block of all proteins, not to mention the DNA molecule; or that sodium and potassium (both alkali metals) are vital in the functioning of brain and nervous system cells.

And hence the generally light-hearted, whimsical tone allows him to make fanciful connections: calcium is a key ingredient in the bones of endoskeletons and the shells of exoskeletons, compacted dead shells made chalk, but in another format made the limestone which the Romans and others ground up to make the mortar which held their houses together.

Then there is magnesium. I didn’t think magnesium was particularly special, but learned from Atkins that a single magnesium atom is at the heart of the chlorophyll molecule, and:

Without chlorophyll, the world would be a damp warm rock instead of the softly green haven of life that we know, for chlorophyll holds its magnesium eye to the sun and captures the energy of sunlight, in the first step of photosynthesis. (p.16)

You see how the writing is aspiring to an evocative, poetic quality- a deliberate antidote to the dry and factual way chemistry was taught to us at school. He means to convey the sense of wonder, the strange patterns and secret linkages underlying these wonderful entities. I liked it when he tells us that life is about capturing, storing and deploying energy.

Life is a controlled unwinding of energy.

Or about how phosphorus, in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a perfect vector for the deployment of energy, common to all living cells. Hence the importance of phosphates as fertiliser to grow the plants we need to survive. Arsenic is such an effective poison because it is a neighbour of phosphorus, shares some of its qualities, and so inserts itself into chemical reactions usually carried out by phosphorus but blocking them, nulling them, killing the host organism.

All the facts I explained in the first half of this post (mostly cribbed from the LiveScience.com website) are not reached or explained until about page 100 of this 150-page-long book. Personally, I felt I needed them earlier. As soon as I looked at the big diagram of the table he gives right at the end of the book I became intrigued by the layout and the numbers and couldn’t wait for him to get round to explaining them, which is why I went on the internet to find out more, more quickly, and why Istarted my review with a factual summary.

And eventually, the very extended conceit of ‘the kingdom’ gets rather tiresome. Whether intentional or not, the continual references to ‘the kingdom’ begin to sound Biblical and pretentious.

Now the kingdom is virtually fully formed. It rises above the sea of nonbeing and will remain substantially the same almost forever. The kingdom was formed in and among the stars.. (p.75)

The chapter on the scientists who first isolated the elements and began sketching out the table continues the metaphor by referring to them as ‘cartographers’, and the kingdom as made of islands and archipelagos.

As an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Jena, [Johann Döbereiner] noticed that reports of some of the kingdom’s islands – reports brought back by their chemical explorers – suggested a brotherhood of sorts between the regions. (p.79)

For me, the obsessive use of the geographical metaphor teeters on the border between being useful, and becoming irritating. He introduces me to the names of the great pioneers – I was particularly interested in Dalton, Michael Faraday, Humphrey Davy (who isolated a bunch of elements in the early 1800s) and then William Ramsey – but I had to go to Wikipedia to really understand their achievements.

Atkins speculates that some day we might find another bunch or set of elements, which might even form an entire new ‘continent’, though it is unlikely. This use of a metaphor is sort of useful for spatially imagining how this might happen, but I quickly got bored of him calling this possible set of new discoveries ‘Atlantis’, and of the poetic language as a whole.

Is the kingdom eternal, or will it slip beneath the waves? There is a good chance that one day – in a few years, or a few hundred years at most – Atlantis will be found, which will be an intellectual achievement but probably not one of great practical significance…

A likely (but not certain) scenario is that in that distant time, perhaps 10100 years into the future, all matter will have decayed into radiation, it is even possible to imagine the process. Gradually the peaks and dales of the kingdom will slip away and Mount Iron will rise higher, as elements collapse into its lazy, low-energy form. Provided that matter does not decay into radiation first (which is one possibility), the kingdom will become a lonely pinnacle, with iron the only protuberance from the sea of nonbeing… (p.77)

And I felt the tone sometimes bordered on the patronising.

The second chemical squabble is in the far North, and concerns the location of the offshore Northern Island of hydrogen. To those who do not like offshore islands, there is the problem of where to put it on the mainland. This is the war of the Big-Endians versus the Little-Endians. Big-Endians want to tow the island ashore to form a new Northwestern Cape, immediately north of lithium and beryllium and across from the Northeastern Cape of helium… (p.90)

Hard core chemistry

Unfortunately, none of these imaginative metaphors can help when you come to chapter 9, an unexpectedly brutal bombardment of uncompromising hard core information about the quantum mechanics underlying the structure of the elements.

In quick succession this introduces us to a blizzard of ideas: orbitals, energy levels, Pauli’s law of exclusion, and then the three imaginary lobes of orbitals.

As I understood it, the Pauli exclusion principle states that no two electrons can inhabit a particular orbital or ‘layer’ or shell. But what complicates the picture is that these orbitals come in three lobes conceived as lying along imaginary x, y and z axes. This overlapped with the information that there are four types of orbitals – s, p, d and f orbitals. In addition, there are three p-orbitals, five d-orbitals, seven f-orbitals. And the two lobes of a p-orbital are on either side of an imaginary plane cutting through the nucleus, there are two such planes in a d-orbital and three in an f-orbital.

After pages of amiable waffle about kingdoms and Atlantis, this was like being smacked in the face with a wet towel. Even rereading the chapter three times, I still found it impossible to process and understand this information.

I understand Atkins when he says it is the nature of the orbitals, and which lobes they lie along, which dictates an element’s place in the table, but he lost me when he said a number of electrons lie inside the nucleus – which is the opposite of everything I was ever taught – and then when described the way electrons fly across or through the nucleus, something to do with the processes of ‘shielding’ and ‘penetration’.

The conspiracy of shielding and penetration ensure that the 2s-orbital is somewhat lower in energy than the p-orbitals of the same rank. By extension, where other types of orbitals are possible, ns- and np-orbitals both lie lower in energy than nd-orbitals, and nd-orbitals in turn have lower energy than nf-orbitals. An s-orbital has no nodal plane, and electrons can be found at the nucleus. A p-orbital has one plane, and the electron is excluded from the nucleus. A d-orbital has two intersecting planes, and the exclusion of the electron is greater. An f-orbital has three planes, and the exclusion is correspondingly greater still. (p.118)

Note how all the chummy metaphors of kingdoms and deserts and mountains have disappeared. This is the hard-core quantum mechanical basis of the elements, and at least part of the reason it is so difficult to understand is because he has made the weird decision to throw half a dozen complex ideas at the reader at the same time. I read the chapter three times, still didn’t get it, and eventually wanted to cry with frustration.

This online lecture gives you a flavour of the subject, although it doesn’t mention ‘lobes’ or penetration or shielding.

In the next chapter, Atkins, briskly assuming his readers have processed and understood all of this information, goes on to combine the stuff about lobes and orbitals with a passage from earlier in the book, where he had introduced the concept of ions, cations, and anions:

- ion an atom or molecule with a net electric charge due to the loss or gain of one or more electrons

- cation a positively charged ion

- anion a negatively charged ion

He had also explained the concept of electron affinity –

The electron affinity (Eea) of an atom or molecule is defined as the amount of energy released or spent when an electron is added to a neutral atom or molecule in the gaseous state to form a negative ion.

Isn’t ‘affinity’ a really bad word to describe this? ‘Affinity’ usually means ‘a natural liking for and understanding of someone or something’. If it is the amount of energy released, why don’t they call it something useful like the ‘energy release’? I felt the same about the terms ‘cation’ and ‘anion’ – that they had been deliberately coined to mystify and confuse. I kept having to stop and look up what they meant since the name is absolutely no use whatsoever.

And the electronvolt – ‘An electronvolt (eV) is the amount of kinetic energy gained or lost by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum.’

Combining the not-very-easily understandable material about electron volts with the incomprehensible stuff about orbitals means that the final 30 pages or so of The Periodic Kingdom is thirty pages of this sort of thing:

Take sodium: it has a single electron outside a compact, noble-gaslike core (its structure is [Ne]3s¹). The first electron is quite easy to remove (its removal requires an investment of 5.1 eV), but removal of the second, which has come from the core that lies close to the nucleus, requires an enormous energy – nearly ten times as much, in fact (47.3 eV). (p.130)

This reminds me of the comparable moment in John Allen Paulos’s book Innumeracy where I ceased to follow the argument. After rereading the passage where I stumbled and fell I eventually realised it was because Paulos had introduced three or so important facts about probability theory very, very quickly, without fully explaining them or letting them bed in – and then had spun a fancy variation on them…. leaving me standing gaping on the shore.

Same thing happens here. I almost but don’t quite understand what [Ne]3s¹ means, and almost but don’t quite grasp the scale of electronvolts, so when he goes on to say that releasing the second electron requires ten times as much energy, of course I understand the words, but I cannot quite grasp why it should be so because I have not understood the first two premises.

As with Paulos, the author has gone too fast. These are not simple ideas you can whistle through and expect your readers to lap up. These are very, very difficult ideas most readers will be completely unused to.

I felt the sub-atomic structure chapter should almost have been written twice, approached from entirely different points of view. Even the diagrams were no use because I didn’t understand what they were illustrating because I didn’t understand his swift introduction of half a dozen impenetrable concepts in half a page.

Once through, briskly, is simply not enough. The more I tried to reread the chapter, the more the words started to float in front of my eyes and my brain began to hurt. It is packed with sentences like these:

Now imagine a 2 p-electron… (an electron that occupies a 2 p-orbital). Such an electron is banished from the nucleus on account of the existence of the nodal plane. This electron is more completely shielded from the pull of the nucleus, and so it is not gripped as tightly.In other words, because of the interplay of shielding and penetration, a 2 s-orbital has a lower energy (an electron in it is gripped more tightly) than a 2 p-orbital… Thus the third and final electron of lithium enters the 2 s-orbital, and its overall structure is 1s²2s¹. (p.118)

I very nearly understand what some of these words meant, but the cumulative impact of sentences like these was like being punched to the ground and then given a good kicking. And when the last thirty pages went on to add the subtleties of electronvoltages and micro-electric charges into the mix, to produce ever-more complex explanations for the sub-atomic interactivity of different elements, I gave up.

Summary

The first 90 or so pages of The Periodic Kingdom do manage to give you a feel for the size and shape and underlying patterns of the periodic table. Although it eventually becomes irritating, the ruling metaphor of seeing the whole place as a country with different regions and terrains works – up to a point – to explain or suggest the patterns of size, weight, reactivity and so on underlying the elements.

When he introduced ions was when he first lost me, but I stumbled on through the entertaining trivia and titbits surrounding the chemistry pioneers who first isolated and named many of the elements and the first tentative attempts to create a table for another thirty pages or so.

But the chapter about the sub-atomic structure of chemical elements comprehensively lost me. I was already staggering, and this finished me off.

If Atkins’s aim was to explain the basics of chemistry to an educated layman, then the book was, for me, a complete failure. I sort of quarter understood the orbitals, lobes, nodes section but anything less than 100% understanding means you won’t be able to follow him to the next level of complexity.

As with the Paulos book, I don’t think I failed because I am stupid – I think that, on both occasions, the author failed to understand how challenging his subject matter is, and introduced a flurry of concepts far too quickly, at far too advanced a level.

Looking really closely I realise it is on the same page (page 111) that Atkins introduces the concepts of energy levels, orbitals, the fact that there are three two-lobed orbitals, and the vital existence of nodal planes. On the same page! Why the rush?

An interesting and seemingly trivial feature of a p-orbital, but a feature on which the structure of the kingdom will later be seen to hinge, is that the electron will never be found on the imaginary plane passing through the nucleus and dividing the two lobes of the orbital. This plane is called a nodal plane. An s-orbital does not have such a nodal plane, and the electron it describes may be found at the nucleus. Every p-orbital has a nodal plane of this kind, and therefore an electron that occupies a p-orbital will never be found at the nucleus. (p.111)

Do you understand that? Because if you don’t, you won’t understand the last 40 or so pages of the book, because this is the ‘feature on which the structure of the kingdom will later be seen to hinge’.

I struggled through the final 40 pages weeping tears of frustration, and flushed with anger at having the thing explained to me so badly. Exactly how I felt during my chemistry lessons at school forty years ago.

Related links

Reviews of other science books

Chemistry

Cosmology

- The Perfect Theory by Pedro G. Ferreira (2014)

- The Book of Universes by John D. Barrow (2011)

- The Origin Of The Universe: To the Edge of Space and Time by John D. Barrow (1994)

- The Last Three Minutes: Conjectures about the Ultimate Fate of the Universe by Paul Davies (1994)

- A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes by Stephen Hawking (1988)

- The Black Cloud by Fred Hoyle (1957)

The Environment

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert (2014)

- The Sixth Extinction by Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin (1995)

Genetics and life

- Life At The Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life by J. Craig Venter (2013)

- What Is Life? How Chemistry Becomes Biology by Addy Pross (2012)

- Seven Clues to the Origin of Life by A.G. Cairns-Smith (1985)

- The Double Helix by James Watson (1968)

Human evolution

Maths

- Alex’s Adventures in Numberland by Alex Bellos (2010)

- Nature’s Numbers: Discovering Order and Pattern in the Universe by Ian Stewart (1995)

- Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences by John Allen Paulos (1988)

- A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper: Making Sense of the Numbers in the Headlines by John Allen Paulos (1995)