Anecdote or art?

In 1877 the American artist Whistler sued the English critic John Ruskin for libel. Ruskin had written of Whistler’s painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket that he had

never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face

During the trial Whistler said many interesting things, including explaining to the judge that the painting was not intended to be an accurate scientific portrait of the fireworks at Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea. It had been composed to create artistic interest as opposed to anecdotal interest.

It is ironic that this statement is quoted in the sixth and final room of the Whistler exhibition at the Dulwich picture Gallery entitled An American in London: Whistler and the Thames because the exhibition, in its layout, content and the way I overheard it being perceived, is overwhelmingly anecdotal.

Rather than concentrating on form and design for their own sakes, the exhibition places Whistler’s etchings and paintings of the Thames next to late Victorian maps and photographs to repeatedly emphasise the anecdotal and factual basis of the images.

James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler (1834 to 1903), American artist and dandy, was born in Lowell Massachussetts, studied in Paris, then arrived in London in 1859. He made an immediate splash, this long-haired aesthete with his velvet suits, his witty quotes, friendship with the young Oscar Wilde as well as all the young artists of the day, for example, Rossetti and Millais.

Room 1

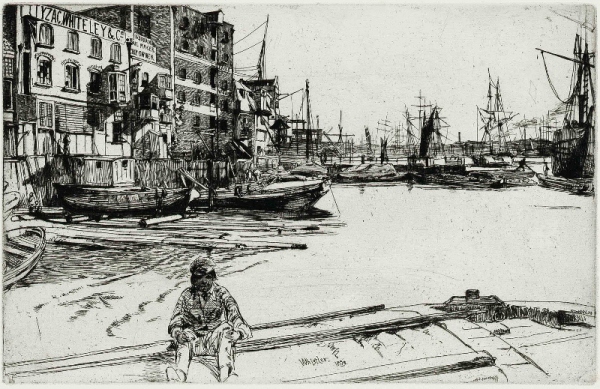

Highlights Whistler’s earliest works, his etchings of the Thames – a hard-working river in the 1860s – cluttered with sailing ships, cutters and tugs, as well as miles of ramshackle and picturesque riverside wharves and workshops. Each one is meticulously described alongside contemporary locations and maps of 1860s London.

Eagle Wharf, from ‘A Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes on the Thames’, 1859, Published 1871, by James Abbott McNeill Whistle

In 1863, Whistler settled on the Thames at Chelsea, becoming neighbour to Rossetti and Swinburne. Etchings he’d made throughout the 1860s were gathered in The Thames Set (1871). The etching Limehouse (1859) features the Bunch of Grapes pub which, the caption informs us, was immortalised by Dickens as the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters in Our Mutual Friend.

Room 2

Contains early paintings and these are not good. Whistler was fascinated by old Battersea Bridge close to his home and made etchings and paintings of it such as Grey and Silver Old Battersea Bridge (1878).

Room 3

Contains more paintings such as the famous Wapping (1864). Here again the commentary is keen to root the image in historical and biographical anecdote, so we learn that the woman with the smudgy face in the centre is Whistler’s mistress.

Apparently, a common contemporary criticism of Whistler’s paintings was that they looked unfinished, with details and surfaces left underdone. Actually, there IS something unfinished and unsatisfactory about many of the paintings in this exhibition.

Also he is not good at painting faces, something which held him back in a great age of Society portraitists such as John Singer Sargeant.

Take Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl (1864). As usual the commentary tells us about the subject of the painting, and about the growing influence of Japanese design – the movement known as japonisme – symbolised by the vase, the spray of flowers and the fan the lady is holding. (The same fan is included in the exhibition just in case we don’t get the point.) And the commentary explains that using a title usually reserved for a piece of music – symphony – is also a piece of daring experimentalism. Art for Art’s sake, Aestheticism etc.

Yes. But it’s not really a very good painting. As a composition it isn’t really that arresting. And the face in the mirror is poor. Bad. As soon as you notice how poor it is, it’s difficult not to let it influence your reading of the whole thing.

As London’s leading aesthete Whistler created a Palace of Art at the White House in Tite Street, Chelsea. The English establishment reacted, as it so often does to artists who fly too high – by ruining him.

The libel case Whistler brought against Ruskin, and which is the focus of room 6, led to his bankruptcy in 1879, the selling-off of all his possessions and works… although Whistler continued to live in the same house until his death in 1903.

Room 4

There was something to admire in every room – just not necessarily to love. For example, Battersea reach from Lindsey House painting (1879) unfinished, yes, but atmospheric. Spot the Japonism! (the ladies with Japanese fans at bottom).

Or a later etching, The Adam and Eve, Old Chelsea. The etchings are like superior book illustrations. They would make good table mats or prints hung up in an old pub. I.e. they are attractive to look at but… but… the interest, the appeal is more anecdotal than artistic.

The Adam and Eve, Old Chelsea by Whistler

All around me people were peering at the etchings and comparing them with the photographs which the exhibition hangs next to as many works as it can – and then locating them on the old maps of London which are also thoughtfully provided – and wondering out loud how much Battersea and Chelsea have changed. Is that where PC World is now? My! hasn’t it all changed!

Anecdote, not aesthetic.

Room 5

I liked the Nocturne (1878). This seemed to me a rare example of a Whistler painting which really successfully achieved what it set out to do, impressionistically creating the sense, the feel, of fog over the Thames.

Room 6

Devoted to the Great Anecdote which squats at the centre of Whistler’s career like an ugly toad. The Ruskin libel case which exonerated the painter but ruined him, because the wealthy patrons he’d spent decades building up, abandoned him in droves, he lost all his income and eventually went bankrupt in 1879.

This final room contains more etchings and preparatory paintings of Battersea Bridge but not the one which prompted the trial – Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket – instead displaying the related but significantly different Nocturne Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge.

Conclusion

I was disappointed. I like this period of history and culture, I love London history and views, I am sympathetic to Impressionism and post-Impressionism and late-19th century art of all types – and yet this exhibition didn’t do it for me.

It left me feeling Whistler was a smaller figure than I had previously thought: a name in the history of culture; a catalyst for new ways of thinking, maybe; the victim of a typically English Establishment stitch-up. for sure.

The 30 or more etchings I liked as interesting book illustrations, some of amazing detail and character; but almost none of the paintings did it for me, and I left feeling a lot of them really were the unfinished daubs which his critics accused him of.

The promotional video

Related links

- An American in London: Whistler and the Thames continues at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 12 January 2014